You might not expect to see big money moves out of Portland City Hall right now, considering the tight budget constraints most city bureaus are under. But when it comes to the Portland Clean Energy Fund (PCEF), it’s a different story — and the latest news out of this program should be very exciting to transportation advocates in Portland.

Among the investments proposed is $20 million for an electric bike rebate program.

Managed by the Bureau of Planning and Sustainability (BPS), PCEF is funded by revenue the city collects from large retailers (1% tax on large retailers with $1 billion in national revenue and $500,000 in revenue in Portland) and is dedicated “community-led projects that reduce carbon emissions, create economic opportunity, and help make our city more resilient as we face a changing climate.”

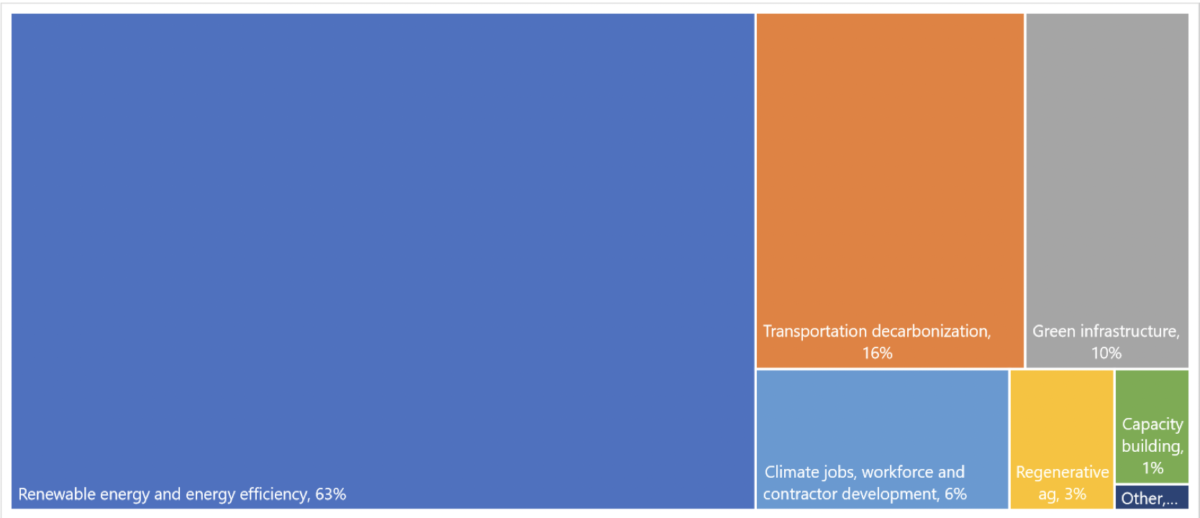

In the past, the PCEF program hasn’t always paid very much attention to the importance of transportation as a climate action strategy. But last year, the program made some changes, dedicating a significant pot of money to transportation decarbonization efforts. The PCEF’s Climate Investment Plan Preliminary Draft released earlier this week gives us a first look of what kinds of projects this might fund.

Out of its $750 million total five-year budget, the PCEF has $100 million over the next five years (2023- 2028) to spend on projects related to transportation decarbonization. This money will be spent on both “strategic programs,” which are large-scale investments managed by the city and designed with input from community members and subject experts and “community responsive grants” awarded to community-based nonprofit organizations designing carbon emissions reduction projects.

A local e-bike rebate program

One of the strategic plans outlined in the draft plan is for an electric bike rebate program with $20 million of funding over the next five years. This would be separate from the $6 million statewide e-bike rebate program currently being debated at the Oregon Legislature. And it might turn out to be a crucial Plan B given that House Bill 2571 is very likely to be much smaller than advocates originally hoped (sponsors are working on new bill language that would include many significant compromises from the original version — more on that coming soon.)

It’s clear from the Climate Investment Plan that PCEF committee members are bullish on e-bikes: “E-bikes provide an efficient way to get around Portland, are not subject to vehicle congestion, do not require much physical exertion, offer trip flexibility, and save money and time with respect to parking,” the draft plan states. “Community education and incentives are needed to provide equitable access to e-bikes, as well as safety equipment, lighting, weatherproof gear, charging infrastructure, secure storage areas, and locks.”

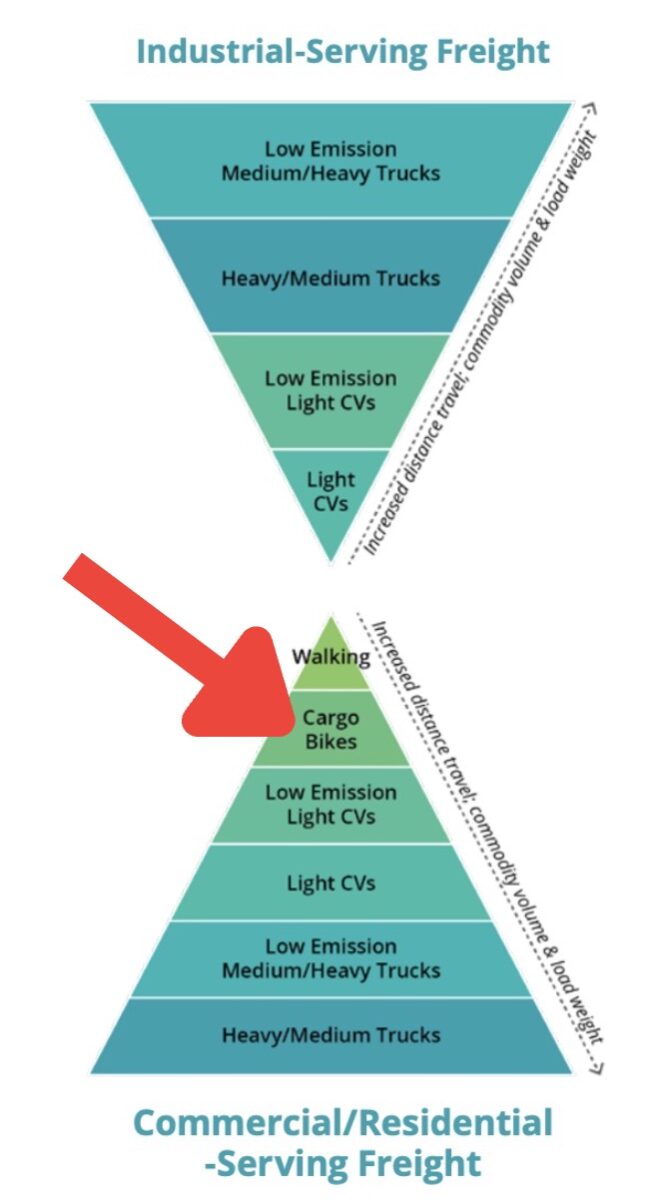

This program would give income-qualified households rebates for e-bike and cargo e-bikes from local bike retailers. Local bike retailers will need to be physically located in Portland and provide bike repair services.

“The program will be conducted in parallel with education and outreach by community-based organizations to PCEF priority populations about the e-bike opportunity, including information about safe riding, route-finding, charging, and storage. Surveys and data will be collected about e-bike use, storage, and charging, including recommendations for a pilot program for allocating funds for safe e- bike storage and charging needs for existing multifamily properties,” the plan states.

PCEF planners also want to invest $25 million in an expansion of the Portland Bureau of Transportation’s highly successful Transportation Wallet program, which offers transit passes and Biketown/scooter-share ride credits to income-qualified Portlanders. This would give PBOT the ability to issue transportation wallets to a lot more Portlanders.

$35 million of opportunity for local nonprofits

In addition to the two projects above, the plan would invest an additional $35 million in grants over the next five years to nonprofit organizations to help them “identify community mobility needs and solutions and prepare them to implement environmentally sustainable transportation projects.” According to the preliminary draft, these grants could support efforts in:

- Community-driven transportation projects that reduce vehicle miles traveled.

- Access to clean transportation through the electrification of fleet vehicles including shared vehicles managed by community organizations and electric bikes (e.g., e-bike libraries, e-cargo bikes).

- Charging infrastructure that is equitable, convenient, reliable, affordable, and accessible.

- Overcoming barriers to accessing clean transportation.

- Providing outreach and education for clean transportation including new mobility options.

- Building capacity of organizations to implement clean transportation projects.

- Support workforce development and training programs that provide economic opportunities in the clean transportation sector.

So, transportation nonprofit people, it might be time to start thinking of grant application ideas that fit these criteria.

From here, the CIP must be recommended by the PCEF advisory committee to City Council later this summer. Then City Council will need to approve the CIP before solicitations for specific projects are released. BPS will host an in-person PCEF workshop this Saturday, March 18 at CORE – Collective Oregon Eateries on 82nd Ave from 1 to 4 pm (RSVP for the event here). There will also be a virtual public workshop on March 22 (info here). And an online survey is available to fill out until the end of the month, which you can find here.