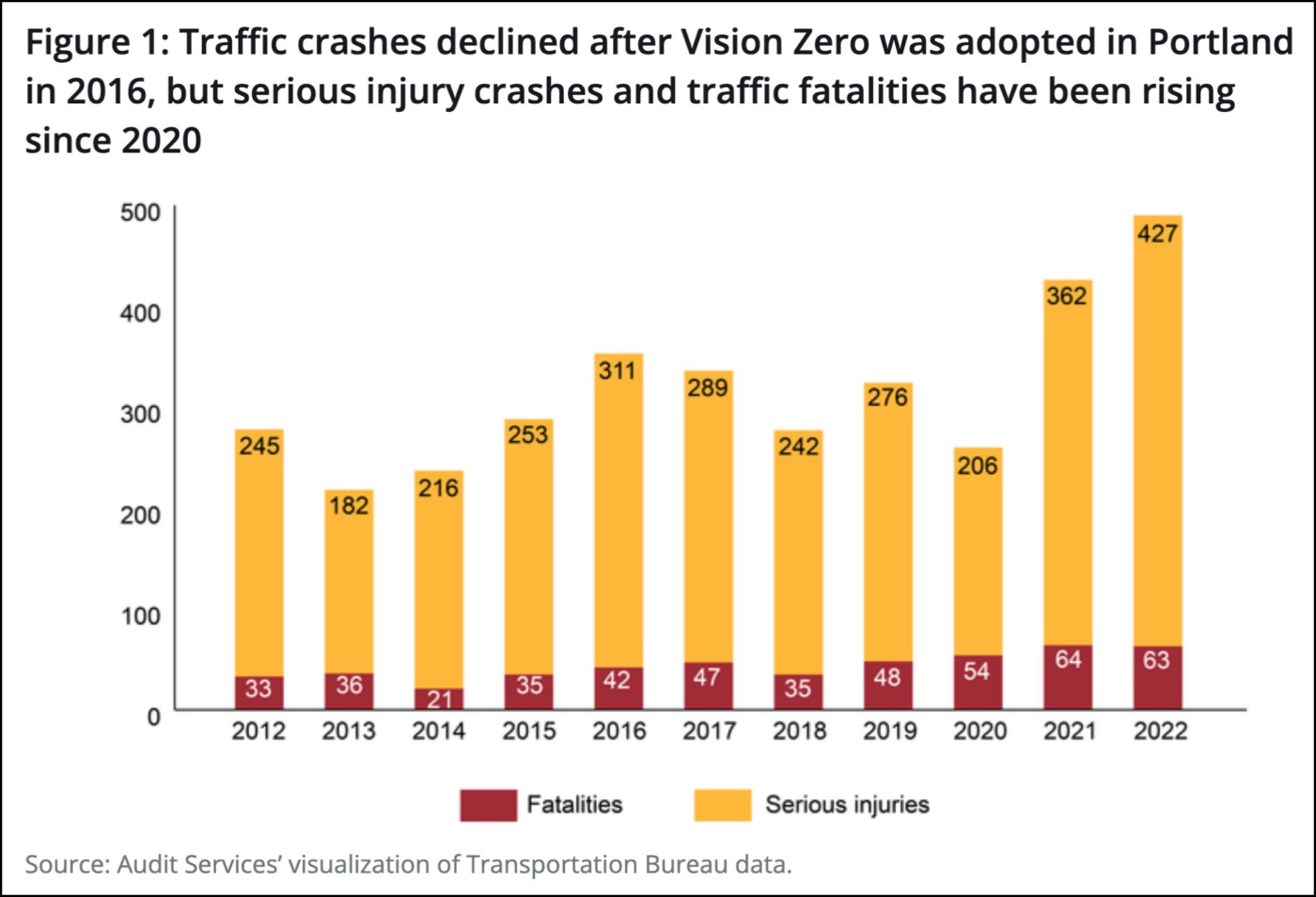

The Portland City Auditor has released a report on the transportation bureau’s Vision Zero program. Vision Zero, a framework for decision-making with the goal of no traffic deaths, was adopted by Portland City Council as a goal in 2016. Since then, the annual fatality trendline has spiked upward. The auditor noted progress on some safety projects; but found incomplete work on other fronts. The report says the Portland Bureau of Transportation needs to refine its approach to equity and, “systematically evaluate whether its safety projects reduce traffic deaths and serious injury crashes.”

For several years now, the Portland Bureau of Transportation has weathered criticism about its Vision Zero program. The idea, adopted from road safety experts in Sweden, first came to town in 2010 when a public health researcher visited Portland and called the question: “Why do we allow these deaths to occur?” The idea grabbed hold of cycling and transportation advocates were eager to have a mechanism to build urgency for safer street designs and more human-centered mobility policies. By 2015, Vision Zero had firmly ensconced itself as one of the top priorities at PBOT.

Nine years later, the Vision Zero is more commonly the punchline of criticisms than the proud rallying cry many of us hoped it would be. While I quibble with the lazy scapegoating and lack of self-reflection from many who question its value as an organizing principle, the facts are inescapable. Whatever PBOT is doing is not keeping up with the threats posed on our streets by dangerous driving. When Vision Zero first gained favor in 2010, we had just 26 people die on Portland streets. We’ve averaged around 70 fatalities for the past three years and are on track for another tragically high tally this year.

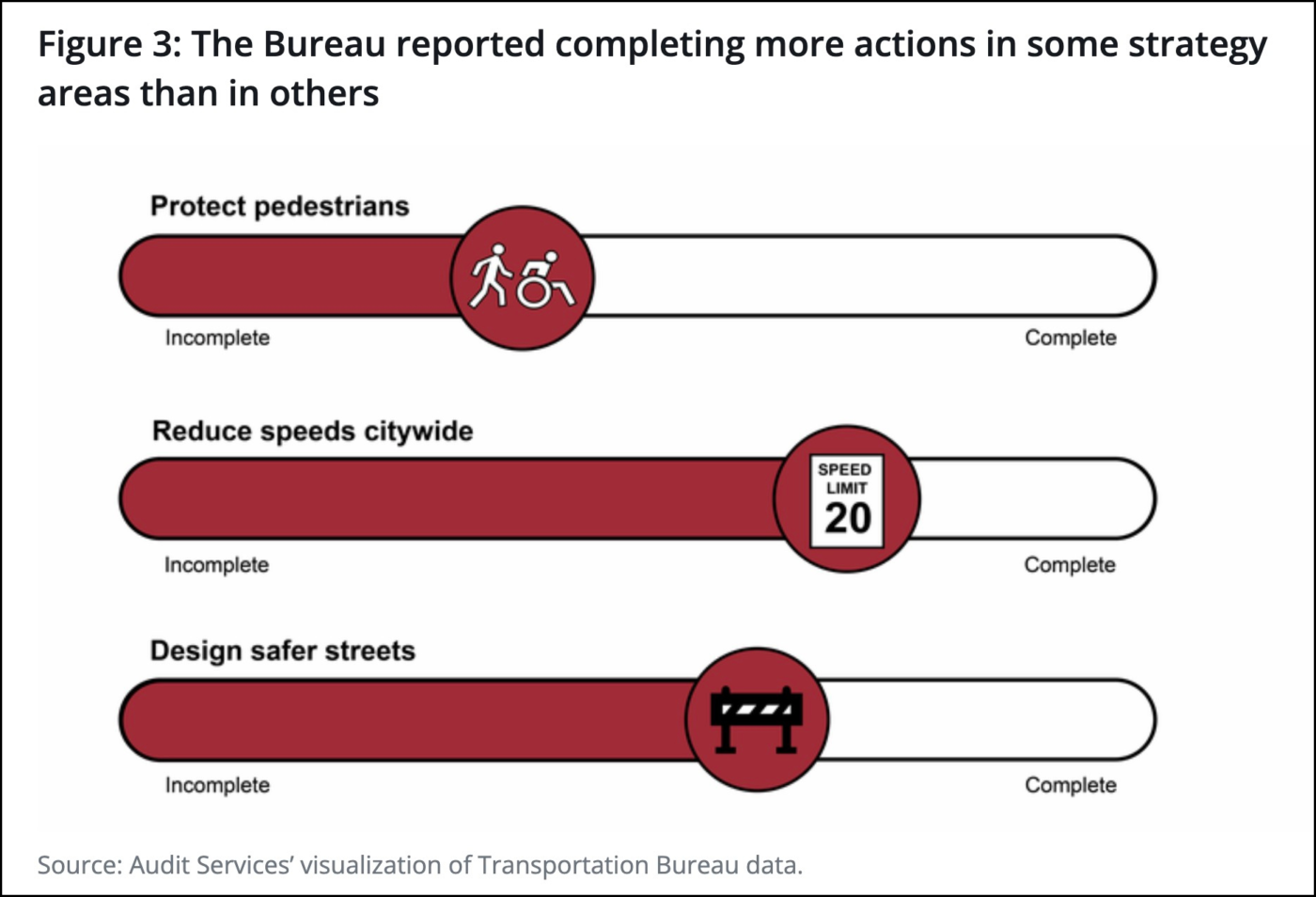

The audit focused on PBOT’s Vision Zero work since 2019 when the bureau made it a key part of their strategic plan and council adopted an update on the program. In that 2019 update, PBOT listed for main strategies: protect pedestrians, reduce speeds citywide, design streets to protect human lives; and create a culture of shared responsibility. The audit assessed progressed on the first three of those strategies.

When it comes to protecting pedestrians, the report gave a mixed review. PBOT completed key projects like new signal timing and traffic calming projects, but hasn’t added as many streetlights or filled as many crossing gaps as their plan calls for.

The next critique from the report won’t come as a surprise to anyone: The Auditor found that PBOT has done a good job reducing speed limits, but hasn’t done enough to make sure they’re enforced — either by automated cameras or via police. In the first seven years of the speed camera program, PBOT had installed just nine cameras at five locations. Officials have blamed everything from contractor and supplier issues, to design problems, vandalism, and electrical challenges for the delay. The logjams appeared to be resolved last year.

The best grades given to PBOT in this report are in their efforts to redesign streets and corridors. “The bureau did well in most of its strategy to design streets to be safer for everyone,” the report states.

While its clear PBOT has ticked off many important boxes on their Vision Zero plan, the main takeaway of the Auditor’s report is that PBOT isn’t doing enough to prove the projects are actually making roads safer. Not only is PBOT not do routine systematic evaluations of completed projects, the Auditor said, “We found confusion within the Bureau as to what constitutes a Vision Zero project.”

Here’s more from the report:

Without systemic evaluation of safety outcomes, the Bureau is missing the opportunity to create more alignment between the work they do on safety projects and the overall goal of Vision Zero. A more systematic approach would allow trends to be identified and analyzed to better understand the outcomes of completed projects, and which may need to be altered or dropped. As traffic deaths continue to increase it is vital that the Bureau consistently evaluate completed safety projects so they can see which are working best at shifting the trend towards the intended goal of zero traffic deaths and serious injuries.

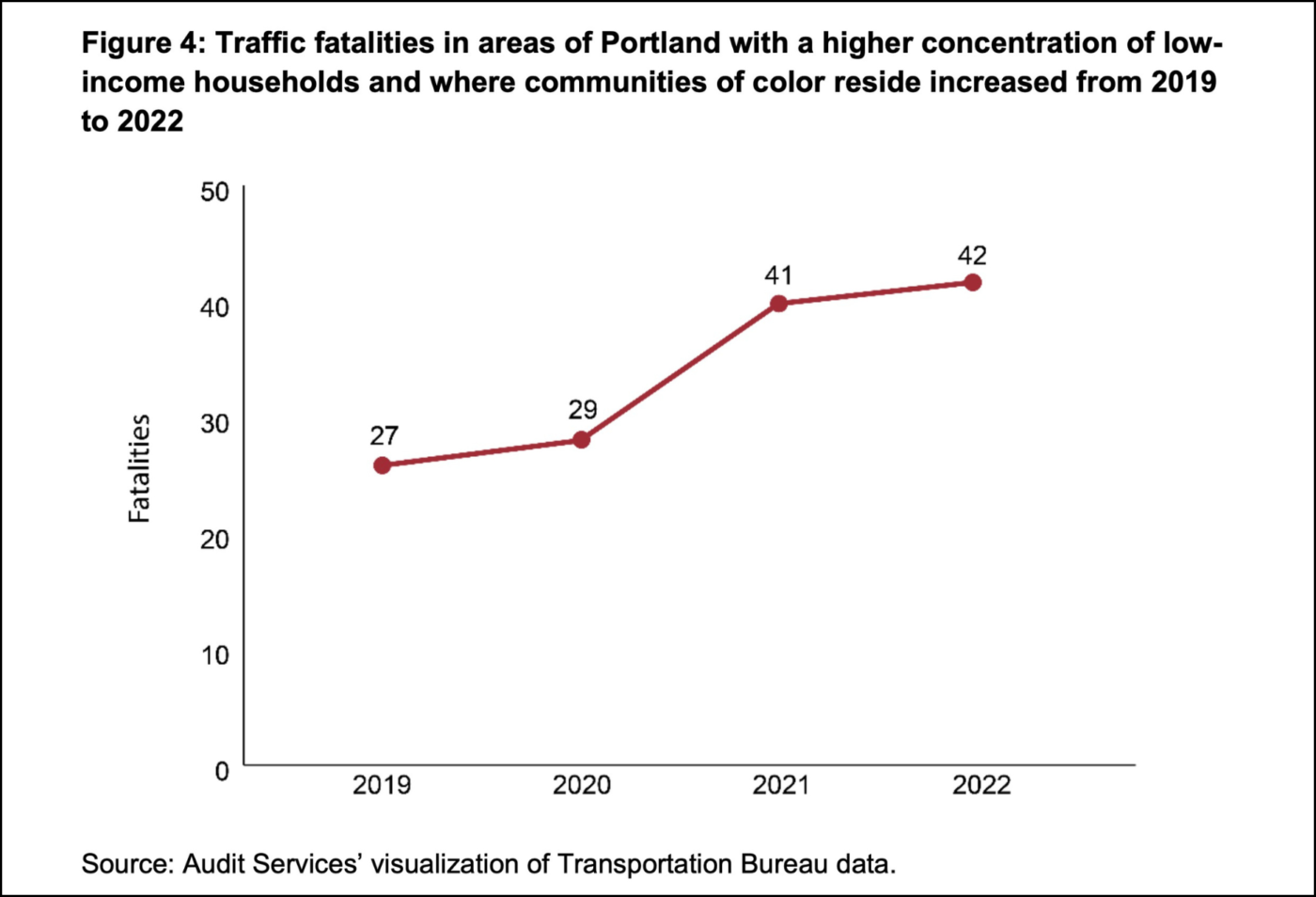

Given how important equity has become as a “north star” for PBOT in recent years, the report’s advice on the subject is notable. The Auditor says PBOT’s current approach to making sure safety focuses on areas with a higher percentage of low-income people and Portlanders of color, puts too much emphasis on large-scale corridor projects. The report says PBOT should focus on a more micro level. This insight came from audit staff who joined a series of community walks in east Portland and learned:

There are many dynamics at play within the city that impact where people live, play and congregate, which present more opportunities for equitable safety improvements if other sources of data, such as community stories, are used. The current methodology for incorporating equity in its decision-making may prevent the Bureau from considering other opportunities to address safety needs equitably, such as smaller-scale improvements that may evolve out of these other sources.

The City Auditor made three recommendations for PBOT: create a plan that closely ties safety projects to expected outcomes; install all promised speed cameras; and make sure a revised Vision Zero approach zooms into “smaller-scale improvements” to address equity goals.

None of the findings will come as a surprise to PBOT staff or leadership. My hunch is many folks in the bureau are glad to have this audit as a way to get more attention on their work. It will be interesting to see how Vision Zero changes and how these audit recommendations are operationalized under the new government structure and their new boss, Deputy City Administrator of the Public Works Service Area Priya Dhanapal.

Thanks for reading.

BikePortland has served this community with independent community journalism since 2005. We rely on subscriptions from readers like you to survive. Your financial support is vital in keeping this valuable resource alive and well.

Please subscribe today to strengthen and expand our work.

PBOT a couple years ago made Capitol Hwy through Hillsdale 20mph. Makes sense since its a town center with a lot of commercial activity, a high school nearby, and a fair bit of pedestrian activity.

While enforcement of the speed limit would be a welcomed addition, the road design has not been updated to reflect a 20mph street and is still a wide straight multilane road with no traffic calming features. Because of that, it requires a significant amount of cognitive discipline to go 20mph and not so shockingly most people naturally go at least 30mph.

I truly believe some cheap and quick design elements (that aren’t ugly) with some slight differences in how the lanes are painted could make a huge difference.

One common option is to add a white fog line on the right-hand side wherever there isn’t already one (for example, for a painted bike lane or a turn lane) and reduce the lane width to 9 feet. Another option that PBOT has already tried on the east side (SE Main east of 130th) is to eliminate all pavement markings altogether except crosswalks, including the center yellow, and make it a 20-mph residential street.

I think this is the area they’re talking about: overhead street view

While adding a fog line and stuff is reasonable, this area already has one, and with the number of people out and about there it would be cool to take back some of the lanes to use for public seating/buffer space, because it’s kinda all parking lots and road there.

This is just one idea, but in downtown Raleigh (street view) along the main street they removed all the lane markings and yellow and created an open two-way plaza, something like one often sees in Europe. By making the whole area more pedestrian-oriented, land values increased enough that several new buildings have been added in recent years. If you look closely you’ll find that the rain gutter for the street merges into the sidewalk, making the entire plaza ADA (Raleigh gets more rain than Portland and it tends to come down harder).

This same issue exists on SE Hawthorne, especially heading downhill from 20th to 12th (where it’s two lanes in each direction). I try to religiously follow speed limits as part of an elaborate bit to be annoying to other drivers on the occasions that I do drive (and because it’s the law), but I find it takes a lot of focus to stay at 20. Meanwhile, the annoyed cars behind me are changing lanes and speeding as fast as they can manage just so we can all sit at the same light at 11th and Madison.

If you look at Vision Zero in places where it has actually succeeded, the changes made are much more intensive than anything I’ve seen in Portland. There’s been tons of good stuff, but it’s frustrating to see how car oriented a lot of the designs still tend to be (not to mention how often the chance of maybe removing free on street parking sinks the potential for great solutions).

A good example of a common “vision zero” environment in the USA that actually works are Walmart parking lots – yeah sure they are god awful ugly and a lot of people crash in their lots, but how many actually die or suffer serious injuries, particularly given the huge volume of traffic any one Walmart generates?

There’s countless examples of where the speed limit has been lowered without changing anything about the roadway in Portland and I think it’s the main reason why there is so much hostility towards speed cameras.

When a roadway is purposefully designed with a higher design speed than the speed limit and a speed camera is installed, of course people are going to have opinions that they are just a money grab.

It doesn’t help that there is a long history of such money-grabs. That history is why Oregon cities can’t lower speed limits without state approval.

The spirit of vision zero is to do “too much” to prevent deaths; to overshoot; to be “too disruptive” to everyday conveniences so that another single death does not occur. After that has been accomplished in a short time, then evaluate what is needed, and start building the conveniences back into the system as tolerated.

“Vision zero” was used as a political slogan and not a mandate. The sweet promise without the bitter effort.

PBOT, and pretty much everywhere else in the US, has set zero deaths on the ever receding horizon, by prioritizing solutions that are the most invisibile.

I think that PBOT needs to analyze it’s maintenance data with the idea that damage to potentially protective infrastructure (bollards, barriers, signs, curbs, paint where there shouldn’t be traffic, etc.) is a sign that something is wrong and work to address root causes. Instead they’ve removed traffic diverters that automobiles keep crashing into. That the involved PBOT staff viewed removing the diverters as an acceptable response tells us everything we need to know about institutional attitudes at PBOT regarding Vision Zero.

Absolutely predictable.

City, county and state project management is criminally abysmal in Oregon.

We can’t deliver basic services efficiently but we’re quibbling over luxury, boutique projects and aspirational progressive policies.

They make for better ribbon cutting ceremonies for politicians, whereas basic services don’t provide such opportunities and aren’t at all glamorous.

BikeLoud should bring a big beautiful red ribbon to Council and promise to allow them to cut it if they actually hit the 30% mode share goal. Maybe a gold ribbon if they actually achieve a single year with zero traffic deaths.

There is nothing council can possibly do to get 30% (or 20% or even 10%) of daily trips in Portland to be done by bike in 5 years time. Nothing at all.

In 2023, BIKETOWN served up over a half million trips by bike. Your view is City Council could shut down BIKETOWN, replace all BIKETOWN stations with car parking, and destroy all the BIKETOWN bikes with zero impact on the number of bike trips people take in Portland? There would be absolutely no impact at all?

No, that’s not my view at all.

Oh, and not a peep about how getting rid of the PPB traffic division—then bringing it back with barely anyone staffing it—or how about letting tent camps sprawl all over has tanked pedestrian safety in Portland? It’s a mess out there, with drivers suddenly dealing with people stumbling into the street out of nowhere. And yet somehow, crickets from the usual suspects. But somehow focusing on “equity” is going to fix this? Why am I not surprised at the continued cognitive dissonance?

Half of all Portland pedestrians killed in crashes in 2023 were homeless: Data

https://www.koin.com/news/oregon/half-of-all-portland-pedestrians-killed-in-crashes-in-2023-were-homeless-data/#:~:text=(KOIN)%20%E2%80%94%20Twelve%20of%20the,Portland%20Bureau%20of%20Transportation%20says.

“…with drivers suddenly dealing with people stumbling into the street out of nowhere.” Read the room. We’ve heard this ‘out of nowhere’ business before, that’s where bike riders spend their time by all reports.

Local government has made huge strides in addressing tent camping because that’s what voters demanded. That doesn’t mean all needs have been met of course. There will always be people who aren’t using cars either by choice or because they just can’t afford a car. We’re outside your car and you should not be surprised by that.

I’m still waiting for the groundswell of opinion mandating government to take the fatality out of everyday transportation.

“…or how about letting tent camps sprawl all over has tanked pedestrian safety in Portland? It’s a mess out there, with drivers suddenly dealing with people stumbling into the street out of nowhere. “

Mate…you took that out of context….appears that was referring to the unfortunate instances of homeless in Portland being hit by cars, many of which have substance abuse and mental health problems causing them to be at increased risk for being injured or killed.

The comment seemed to be empathizing with car drivers and putting the blame for the situation on people camping, the people disproportionately getting crushed by cars.

I get it, it’s a bad day when you kill somebody with your car. If only people would bear that in mind when they start it up. Maybe a person is on drugs, but maybe they’re just old and a step slow with a 60 foot wide intersection to cross.

“I see your point, but blaming car drivers entirely misses the broader issue here. Of course, drivers need to be cautious, but let’s not ignore why so many people are in harm’s way to begin with. Policies that encourage people to camp in unsafe, high-traffic areas—like handing out tents and tarps without offering safer alternatives—put lives at risk.

Sure, some individuals might struggle with drugs or mobility, but doesn’t that make it even more vital to get them off the streets and into stable environments? True compassion is about reducing harm, not normalizing dangerous living conditions. If we really care about these individuals, we need to stop enabling a cycle that leads to preventable tragedies.”

And the County is now resuming handing out free tents and tarps. Yet we just voted in Keith Wilson as mayor who opposes this.

https://www.koin.com/local/multnomah-county/homeless-tent-tarp-distribution-winter-controversy/

We also just elected two new county commissioners who are likely to support the tent policy, so it’s not clear that Portlanders are actually opposed to a tents-first housing policy.

There is no “tents-first” policy. This has been explained to you already, but since you insist on repeating this obvious falsehood, I’ve explained it again in my reply to Mary S. below.

According to JOHS data, the county placed nearly 5,500 people in permanent housing and another 7,900 people in shelters in FY 2024. Additionally, of the people receiving housing subsidies in 2023, 87% remained in housing a year later. Is JOHS doing a perfect job? Of course not. But the nonsense claim that the county prioritizes tents and tarps instead of “offering safer alternatives” is not based in reality.

The JOHS claims to have housed or sheltered 12,000 people in 2024? With numbers like that, at some point I’d expect the number of folks camping on the streets to go down.

As someone so clearly concerned with truth and accuracy, I’m sure you can point to evidence that the numbers are wrong. Assuming your beliefs are based on facts rather than feelings, that is.

I didn’t say the numbers were wrong, only that they do not align with my personal experience of the situation on our streets.

It may be that those statistics mean something different than they seem to. Maybe the 7,900 folks JOHS claims it sheltered only stayed one night then got a tent.

I am not accusing anyone of lying.

If there’s nothing wrong with the numbers and they don’t align with your personal experience, then maybe it’s your personal experience that doesn’t match reality.

“then maybe it’s your personal experience that doesn’t match reality”

Or maybe the numbers don’t mean what you think they mean.

Even if you somehow believe that thousands of people refused shelter in favor of a free tent, there were still 5,477 people placed in permanent housing in FY 2024. Once again, the “tents first” narrative has no basis in reality.

As a person who’s worked with government workers/bureaus, they do know how to massage numbers to show what they want the numbers to show. In some bureaus they have dedicated staff to do just that.

Like others, I have yet to see a reduction in numbers on the streets so I would take JOHS “reports” with a bucket of salt.

Your personal experience is pretty meaningless unless you’ve been personally standing outside shelters counting people going in and out.

Lots of things could increase the amount of unsheltered homelessness even as more people are entering housing and shelters. Rising eviction rates, for one. A general lack of affordable housing, for another.

Do you also take official crime statistics with a “bucket of salt”, or are those somehow above scrutiny?

The bigger picture is that this all – Aggressive/Inattentive drivers, bad infrastructure, lack of enforcement, abandoning people down on their luck and calling it “compassion” – stems from one basic thing:

American’s as a whole are indifferent to the death and suffering of other people. It is part of the DNA of the “rugged, indivdualist” archetype that we believe we spring from.

“American’s as a whole are indifferent to the death and suffering of other people.”

Do you really believe that? I don’t.

At the individual level I see a lot of compassion, and at the policy level I see a lot of difficult choices and inept leadership.

The obvious reason why the report would not mention getting rid of the PPB’s traffic division (if it’s even true it doesn’t mention it, since this article is only a summary of the report, and the article notes that the police ARE mentioned in the report in regard to speeding enforcement) is that the report is an analysis of PBOT’s performance, not the Police Bureau’s.

Q,

Alright, let me break this down for you in a way that cuts through the fluff:

So back in 2020, the Portland Police Bureau’s Traffic Division got the axe. Why? Because they were short on cash, short on staff, and trying to juggle too much at once. Chief Chuck Lovell basically said, “Look, we’ve got barely enough people to handle 911 calls, so traffic enforcement? Yeah, that’s going on the back burner.”

This all went down while everyone was calling for police reform and shifting funds around. It sounded good in theory, but in practice? It left Portland without a traffic squad and mayhem on the streets exploded. Fast forward a couple of years, and surprise—traffic deaths hit record highs. Who could’ve guessed?

If you ask me, this is what happens when you try to solve problems with slogans instead of actual solutions.

After dissolving its traffic division in 2020, traffic deaths broke a 70-year record. In 2022, 63 people were killed in traffic crashes, equal to a 30-year-high record in 2021. Those deaths included 31 pedestrians who were killed, reaching historic high levels.

https://www.washingtonexaminer.com/news/2300567/portland-revives-police-unit-as-traffic-deaths-surge/

C’mon. The traffic division was cut by the PPB to help them extort more money from the Portland budget. It was part of the multi-year PPB strike.

“extort more money”

The Trumpy right and the illiberal left think we live in a post-truth world.

Pot, meet kettle.

C’mon, the Mayor ordered in the early days of Covid that Portland Police were not to enforce traffic laws because he didn’t want the officers potentially exposed to Covid and get sick. So didn’t make sense to keep a traffic division if they weren’t supposed to be enforcing laws.

To this day the Mayor has not reversed that order.

While it’s true that they were short staffed, it is completely untrue that it was because of the $15m short fall they suffered.

Even after cutting *UNFILLED* sworn officer positions, they still had “dozens” of unfilled, *FUNDED* positions. That “dozens” is directly from their budget request of the following year.

That short year was still the 3rd highest budget in their history, and they rebounded to record high funding.

The $15m was 20% of the $75m the city suffered. Considering they were getting 33% of the general fund at the time, I’d say they actually did better than the other bureaus.

The issues at PPB go way beyond funding.

That may all be true, but the report was a review of PBOT, not the Police Bureau.

Based on the article’s excerpt from the report about equity, focusing on “equity” may be exactly what should be being done to reduce traffic deaths of homeless people and any other associated Vision Zero issues related to homeless people.

Okay, so let’s talk about this “equity” thing PBOT keeps throwing around. If it’s supposed to make streets safer, why are decisions under that banner nixing proven safety measures like protected bike lanes on Hawthorne or outright removing bike lanes on NE 33rd? It’s like saying you care about safety but then tossing out the tools that actually save lives.

Yes, equity should mean addressing the needs of vulnerable groups, like anyone walking or biking. But decisions like these feel more about optics than outcomes. True equity? It’s making streets safer for everyone—and that starts with infrastructure that protects the most vulnerable, not cutting it.

https://bikeportland.org/2023/12/18/crews-have-scrubbed-off-ne-33rd-ave-bike-lanes-382601

Why do you assume the report was recommending optics and not true equity? It seemed clear that the report WAS recommending protecting the most vulnerable people.

You seem to be confusing PBOT’s work with the Auditor’s report. It wasn’t the Auditor that removed the bike lanes on 33rd, and there’s no indication the report supported that decision, or other PBOT decisions like it.

Okay, that makes things more urgent then. If the most vulnerable and marginalized folks in Portland are dying at a hugely disproportionate rate, then we really ought to have a stronger focus on this whole Vision Zero goal. Getting people off the streets would go a long way, but so would better street design.

While increased surveillance in public places gives me the ick, traffic cams appear to be the only reasonable solution. Every light should have them. Each day when I am out and about I see anywhere from 3-5 people blowing lights. I mean not even close to making it. Some days way more than that. Something’s got to give.

Law and order uber alles.

The problem with those races is that the men who lost had long choo-choo trains of baggage. I wouldn’t call those elections referendums on tents, more like Mozyrsky and Adams were not strong candidates.

(sorry, this comment landed in the wrong thread)

Adams certainly has baggage, anyway. I thought Mozyrsky was fine (though neither he nor Moyer were my first choice).

Nationally, people were obviously unhappy with the way things have been going, especially economically (which is odd given how many people have been telling us what a great president Biden has been, and that we’re better off than ever).

On the local level, however, the election results as a whole do not at all support the idea that Portlanders are fed up with the status quo.

If the election results truly reflect the will of voters, then my understanding of what people want is miscalibrated.

Mozyrsky was the face of the anti-charter reform efforts. He didn’t come off well and I suspect rubbed a lot of plugged-in people the wrong way.

To lose the election, a lot of not-plugged-in people had to like Moyer more, and her non-profit background should have made her very vulnerable to the type of change I believed voters wanted.

Anti Charter reforms efforts? To me that seemed like a strong move for better not just different governance. Morzysky was on the Charter Commission until he resigned in protest for the shenanigans Julia Meier and the other members of the Commission were pulling.

“Vadim Mozyrsky resigned from the Portland Charter Commission partly due to concerns that public opinion polling data was not disclosed to him or to the public. Specifically, a poll conducted earlier in the process indicated strong public support for breaking the proposed reforms into separate measures, with 72% of respondents favoring this approach. However, this data was not shared with the commission members or the public during deliberations. Mozyrsky believed this omission undermined the transparency and integrity of the commission’s work and contributed to his view that the process was preordained rather than inclusive and responsive to public feedback“

https://www.opb.org/article/2022/10/26/portland-voters-consider-massive-overhaul-city-government-november-ballot/

https://www.commonsensegovpdx.com/news-posts/rose-city-reform-vadim-mozyrsky

Angus, I’m talking about the public-facing anti-reform efforts which involved Mapps, Mozyrsky, Gonzalez and (to a lesser extent) Ryan. I’m not going to rehash the recent history that we all just lived through, but Mapps, joined by the others, tried to derail the will of the voters. Even before voters passed charter reform overwhelmingly in 2022, he and Mozyrsky were going out on a limb to spread Fear, Uncertainty, and Dread (FUD) about changing our system. They lost. And then they kept trying to derail things anyway.

Interestingly, those folks have just lost again, in a big way. Even Ryan tarnished the shine of being an incumbent by barely holding his seat.

It’s our new system, and it just worked very well in the recent election. We will soon have a new council which will develop a culture and norms around how the body will function. It is all exciting to see, and I’m looking forward to the next year.

“It’s our new system, and it just worked very well in the recent election.”

Assuming you ignore depressed turnout and the vast numbers of blank ballots in local races.

The new system worked well mechanically, and perhaps achieved an outcome you find politically tasteful, but it’s really too early to tell if the new system achieved the goals proponents publicly claimed it would.

The Oregonian had a good article over the weekend which discusses, among other things, the difference between registered and eligible voters, and Oregon’s adoption of automatic registration about 8 years ago:

https://www.oregonlive.com/politics/2024/11/oregon-voter-turnout-trails-historic-levels.html

It makes the point that,

“Election Lab’s estimates indicate that Oregon is on track to see about 72% eligible voter turnout this year, lower than the state’s 75% rate in 2020 but higher than 68% in 2016 and 64% in 2012.”

“Oregon does not report eligible voter turnout at the county level. But looking at registered voter turnout, it appears that the dip statewide this year is spread across the board, with almost every county reporting lower rates of election participation in 2024 compared to the high point of 2020 and in other recent presidential years.”

But now ProPublica says traffic cameras are racist too. Given our new city council make up, I wouldn’t be surprised if we start ripping out the new traffic cameras in Portland soon. Seems some prefer letting people die in the search for “equity”.

https://www.propublica.org/article/chicagos-race-neutral-traffic-cameras-ticket-black-and-latino-drivers-the-most

Angus, you found one link questioning the racial implications of those cameras and you just keep sharing it and sharing it as if it’s irrefutable dogma.

Here’s another one Jonathan. Just wait until Candace Avalos, Mtich Green & your bestie Sarah Inarone get ahold of this. 🙂

Summery: “Research from the Fines and Fees Justice Center in Washington, D.C., found that predominantly Black neighborhoods often bear the brunt of automated traffic enforcement. While the cameras are meant to be neutral, their placement is frequently in areas with higher proportions of Black residents, who receive more tickets despite no higher rates of traffic crashes in these areas compared to others”.

https://finesandfeesjusticecenter.org/articles/predominantly-black-neighborhoods-in-d-c-bear-the-brunt-of-automated-traffic-enforcement/

nice googling!

My point is we don’t build programs and policy based on studies we find on the internet. They are built by feedback, committees, lobbying, politics, organizing, and so on. And when all those things have happened, we have come up with automated cameras as one solution to a very difficult problem. Cameras can be bad and they aren’t perfect, but a lot of it has to do with who operates the system, where the cameras are placed, what other mitigations are available, what the process is for contesting a violation, and so on.

And save the “your bestie” nonsense. You don’t know me and you don’t know what my values or relationships with other people are like. Thanks.

And you think our dysfunctional city can actually do all these things? We can’t even answer 911 calls in a timely fashion.

In Portland, black drivers die in crashes at disproportional rates. That would suggest that rates of dangerous/illegal driving are also higher among that population group.

What’s our new City Council gonna say about that comment? Avalos, Morillo, Green, Koyama Lane. They’re not going to want to put a single traffic camera in Albina or east of 82nd. IMO, traffic violence is not going to improve in a city with such leaders.

That could be, or there could be other reasons (and I realize you said it “suggests” vs. “shows” or “proves”). Black drivers may live in areas with more dangerous roads, more dangerous driving (including by non-black drivers), poorer medical response times, etc.

You may be right that it could be other reasons, such as a sustained rash of killings of law abiding black drivers by violators of different races. It is possible.

Even (and maybe especially) on dangerous roads, driving within the law greatly reduces your risk of harm.

There is a clear and obvious reason why Black and Latino drivers get ticketed more often in Chicago, and the article touches on that directly. The south side of Chicago (overwhelmingly Black) has seen basically constant disinvestment, industrial sprawl, and hollowing out since at least the 1940s. The urban environment promotes speeding with wide, straight roads and hostile pedestrian environments. It’s often said that there’s one map of Chicago, and it reflects historic disinvestment.

Speed cameras in Chicago are racist insofar as everything with a geographical distribution in Chicago is racist. If we want to fix those problems of racialized disinvestment, we should try harder than putting up speed cameras

Traffic cameras can really only address illegal driving (not “racist geography”), and if street design creates hazardous conditions, it would seem that cameras are more beneficial to local residents than in places where conditions are safer.

I pulled this information together after a discussion at a family dinner the other night:

Oregon – road fatalities are flat over 3 years, PDX increasing.

Finland – road fatalities are dropping over 3 years, Helsinki flat at an average of 6/year.