A person was killed while walking on SE McLoughlin Blvd (Highway 99E) early this morning. It’s the fifth death on the State-owned highway since early 2021 and three of those were pedestrians.

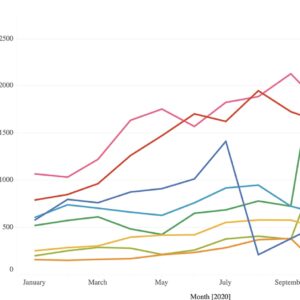

According to our Fatality Tracker, this was the 61st death of 2023 — that’s three more than we had last year and puts us on the same pace as 2021 which was our highest toll since 1990.

Portland first passed its Vision Zero Action Plan in 2016 with a goal to the goal to eliminate traffic deaths and serious injuries on Portland streets by 2025. It’s now crunch-time for that effort. Despite efforts from the Portland Bureau of Transportation and its partners, 372 people have been killed in traffic crashes since 2017 and the numbers are going in the wrong direction.

That’s the sad but true context for the publication of an update to PBOT’s Vision Zero Action Plan released earlier this month. Among the list of actions PBOT says they’ll embark on in the next two years is to pilot new “no turn on red” and “rest on red” traffic signal projects and rekindle their enforcement relationship with the Portland Police Bureau. Here’s what else you need to know about this report…

This is the first update on Vision Zero PBOT has published since 2019 and the 48-page report is meant to guide their work through the 2025 target date. The new action plan provides a helpful snapshot of where things stand and gives advocates a helpful resource to hold the City of Portland accountable.

The report opens with a somber listing of names of everyone who has died in traffic crashes between 2017 and 2022 (above). The 311 names in small font, stack high like skyscrapers above a map of dots that marks where they died. And these are just the dead. The list doesn’t include names of people with seriously, life-changing injuries or the hundreds of family members and friends whose lives will be forever incomplete.

And while the numbers are outrageous and unacceptable, it’s important to remember that PBOT is just one of several government agencies in our city who are responsible for street safety. Metro, Multnomah County, the Portland Police Bureau, and of course the Oregon Department of Transportation, all play major roles. For instance, one of the four main focus areas for “getting to zero” is a new emphasis on “basic needs,” which they’ll lean on partners in housing, job access, drug abuse and mental health services to address.

For their part, PBOT points to some success in the report. They say a pilot program to install left-turn calming bumps at 42 intersections citywide has led to a 13% reduction in turning speeds. The number bike riders hurt or killed on our roads has also trended solidly downward in the past decade. And perhaps PBOT’s best success story comes from their years-long war on speeding. Their analysis shows that speeding is down 71% and top-end speeding (people driving 10 mph or more over the speed limit) has dropped 94% where automated enforcement cameras have been installed. PBOT has also seen an average 72% reduction along corridors where they’ve reconfigured lanes to reduce space for driving.

PBOT also wants the public to know that Portland is not alone in this struggle for safer roads. The report points out that in the last five years there’s been a 17% increase in traffic deaths across the U.S. “Compared to Vision Zero peer

cities in the U.S. with similar population, Portland’s traffic death rate is in the middle,” the report states, next to a chart showing Portland’s rate at 8 deaths per 100,000 residents compared to the national average of 12.

Here are a few more notable stats from the report:

- Pedestrians face the greatest risk in Portland’s transportation network. Roughly 5.7% of Portlanders primarily walk to work, yet 40% of all traffic-related deaths from 2018-2022 were pedestrians.

- Housing status data from 2021 and 2022 police crash reports indicate that 55% of pedestrians killed—30 out of 55—were unhoused when they died.

- Impairment and speed are the two largest contributing factors to fatal traffic crashes, playing a major role in 69% and 42% of all deaths respectively.

- Recent Portland data shows that Black and Indigenous community members died in traffic crashes at about twice the rate relative to their proportion of the population.

- 70% of pedestrian deaths and serious injuries occurred at night (2017-2021).

- Wide streets, which make up 4.5% of Portland streets, accounted for nearly half of all deadly crashes in Portland from 2017-2021 and more than half of pedestrian deaths and serious injury crashes (52%).

- Hit-and-run crashes were up 27% in the last fve years (2017-2021) compared to the fve years prior. Hit-and-run crashes represent one in seven deaths or serious injuries of pedestrians and people biking.

The section on “actions and performance measures” shared a few new things that caught my eye.

PBOT plans to launch a “no turn on red” pilot (above) to reduce risk of turning crashes, “that are particularly dangerous for pedestrians and people bicycling.” This follows growing national attention on the risks of turning on red signals and how that policy is woefully outdated. PBOT has already implemented it at several intersections, but this appears to be an expansion of the policy. Another traffic signal pilot PBOT wants to launch is called, “rest on red.” Here’s how PBOT describes it:

“At night, at some intersections with a history of speed-related crashes, display red lights in all directions to require drivers to slow down as they approach the intersection. Technology at the intersection will detect the vehicle and give a green light.”

The report also addresses a growing push for more physical protection of bike lanes with a promise to develop a list of locations and find funding to “upgrade temporary materials (such as rubber curbs and flexible posts) to permanent materials (such as concrete).”

And it looks like a partnership with the PPB that iced over during the racial justice protests in the summer of 2020 is beginning to thaw. PBOT says they will partner with the (newly bolstered) Traffic Division on “focused enforcement” and to, “ensure training for new police recruits includes data about traffic safety, how to process DUII offenses, and city and state protocol and laws around making traffic stops.”

The narrative that a “massive investment” is needed to stem the tide of deaths is woven throughout the report. As we’ve reported, PBOT is facing its most daunting budget in history and is contemplating vast cuts to staff and programs unless new revenue can be found.

Regardless of the budget situation, the clock is ticking loudly on the City of Portland and their partners when it comes to the woeful trend of tragedies on our streets. We have two years left to make the bold moves necessary to reach our Vision Zero goal.

— Read the Vision Zero Action Plan Update 2023-2025 here. You may also be interested in the annual World Day of Remembrance event (hosted by The Street Trust) on Sunday, November 19th, that will consist of a walk and vigil.

Thanks for reading.

BikePortland has served this community with independent community journalism since 2005. We rely on subscriptions from readers like you to survive. Your financial support is vital in keeping this valuable resource alive and well.

Please subscribe today to strengthen and expand our work.

Some quick thoughts while I’m at work:

I like this idea, but I wonder if motorists might get accustomed to the light turning green for them automatically and get lax about actually slowing down and stopping when they see a red.

Would this involve signing specific intersections? Or are they proposing trialing a city-wide policy change? I know a lot of people want the latter but I feel like that would need to be done at at least the state level with a lot of public outreach to be effective, since it’s changing a long-standing rule of the road.

Another point in favor of Portland splitting off from Multnomah County and becoming its own entity that handles both municipal and county functions. Would be one fewer government structure to deflect responsibility.

I’m also cautiously concerned with how the “Rest on Red” pilot could play out. If drivers who already have an inclination to speed at night know that an intersection is All Red, would some of them be more tempted to blow the light, knowing the crossing traffic also probably has a red?

I live in Montavilla near 82nd, Burnside, Stark, and Glisan – and nighttime speeding is a major safety concern on all these roads.

I also live in Montavilla and you’re right speeding is a problem. The new light timing is helpful when there’s traffic but it basically tempts speeders to go 50 because the timing works out for them if there aren’t other drivers like early in the morning.

That being said I think most drivers aren’t as tuned into the intricacies of transportation planning as people here are so they’ll more often than not slow down if they see red. That is the one thing I notice when I leave for work early in the morning. Now that lights like Mill and Yamhill turn red on a timer it slows down those early morning commuters that normally fly down 82nd.

Motor vehicle operator retraining is an important part of any changes to signal patterns. Presently drivers are pretty accustomed to a green wave. They often accelerate into the back of the string of visible greens which enables speeds above the limit and aggressive passing. People turning off side streets also push it to catch the wave.

MV operators won’t be able to abuse a four way red if they have to put a foot on the ground, press a button, and slow count to 50.

Does Oregon even allow for independent cities like Virginia and Colorado do?

Dunno, but unless the state constitution prohibits independent cities/consolidated city-counties, this is regular legislation change, and I kinda suspect the state legislature would be involved either way.

The good thing about that kind of light design is that it could be super standardized and more or less copy-pasted. Traffic control devices are this 1970s technology that uses a COBOL-like coding language and it can be really expensive to get reprogrammed. (the technology might be getting better, I haven’t checked in a year or two.) Once you get that type of infrastructure installed, you can choose to get creative with the signal timings and methods iteratively because the same code can be deployed everywhere.

“The number bike riders hurt or killed on our roads has also trended solidly downward in the past decade.”

There are a few ways to get to this outcome. Unfortunately, with ridership also trending “solidly downward in the past decade” this is probably just a function of few cyclists to be hurt or killed on our roads to begin with.

why is pbot so low on money?

Because the mayor thinks that reducing parking fees will bring back people to downtown. A large amount of PBOTs budget comes from parking revenue

Just as a thought experiment, would you expect more folks coming downtown if we, say, tripled parking fees? Would parking revenue actually increase? What would the impact be on businesses there?

I think the point they are trying to make is that the cost of parking has little to do with motivating people to come downtown. Few office workers and not much draw for entertainment in downtown, not to mention having to dodge poop and needles while walking around.

What a ridiculous comment.

STAY AWAY FROM DOWNTOWN, ITS TOO SCARY!

Didn’t tell anyone to stay away from downtown or that it’s scary. I’m downtown all the time. You can’t deny that it’s unpleasant to witness so much human suffering.

It really is. I spent three days downtown a few weeks ago and was reminded yet again of the sheer number of hurting people drifting on the streets, yelling at no one in particular. You don’t get that in Lake Oswego or Beaverton, so it’s no wonder why businesses would relocate there. Oh – and no one who works in the burbs pays the hated MultCo homeless services tax. What sweet irony.

The “hated” homeless services tax was passed as a Metro referral, taxes high-income earners in Washington, Clackamas and Multnomah counties, with those revenues redistributed to all three counties.

Depends on what part of downtown we are talking about, and what the particular fee structure would look like. In high demand areas, higher parking fees can help businesses by encouraging more parking turnover (which means more customers). Needless to say if demand is that high, this will also likely increase revenue (to a point). Northwest and the Pearl probably fit this bill, not sure about the traditional downtown areas though.

As a thought experiment, I think that would have almost 0 measurable effect, but would allow PBOT the funding to do its job.

Are you saying that the cost of parking has very little impact on whether people want to visit downtown, and will pay whatever it costs?

Not whatever it costs, but parking is dirt cheap. If we’re talking about places that are in demand enough that we have parking meters, I think the cost can be raised very significantly and have no impact on people deciding if they want to go downtown or not.

It costs $4 an hour to park downtown so you add $8-12 dollars for instance to dine or shop downtown compared to anywhere else in the city.

*** Editor: Deleted last two sentences—argumentative. ***

On-street parking downtown is only $2.20/hr. (plus 20 cents transaction fee). SmartPark garages are only $1.80/hour.

And on-street parking is free after 7 PM. And SmartPark garages are only $5 all night (after 5 PM, until 5 AM).

So if you dine at dinner, best case is arrive at 7 PM and stay for hours, and it’s free on-street. Worst case is $5 in a SmartPark garage. Private off-street garages are typically more, but you don’t have to park in them.

Shopping or dining during the day is more, but even three hours is only $5.40 in a SmartPark garage and not much more on-street.

https://www.portland.gov/transportation/parking/smartpark

https://www.portland.gov/transportation/parking/parking-guide#toc-how-much-does-parking-cost-

Compared to what?

Compared to the cost of driving to and doing whatever it was they were doing in downtown. Parking is the inexpensive part of just about anything you could be doing.

If that’s how people see it, then I can’t imagine why anyone would oppose raising parking fees.

What people claim, as you have suggested elsewhere, isn’t a good indicator of what they actually do. People will say they really care about the fees. And granted, people don’t WANT to pay more. But I contend it would have no impact on their choice to go downtown. Not really. What kind of situation is there where you almost, just barely, want to drive yourself downtown and $5 is going to make or break it.

Which is why Wheeler did his little political stunt and torpedo the fee increase. Not because it actually matters, but because he wanted to be seen as tough on fees. Probably posing for business people and conservatives. It was roundly recognized as a stunt, maybe not by you, when it happened.

I’ll grant you that a modest fee increase probably won’t deter captive drivers such as commuters. But it might be enough to deter some shoppers and have them go elsewhere where the shopping is nearly as good.

I am entirely immune to downtown parking fees, so I have no stake in this debate beyond wanting a healthy and vibrant downtown, but I do know it is a very politically sensitive issue, and that the widespread perception is that increasing parking fees will deter visitors and thus harm downtown.

I don’t know whether it’s true, but it’s a near universal belief, and it drives policy.

We need to make downtown cool, and have things people want to go see. Tripling parking fees won’t do much, I’d rather see PBOT NOT rely on money from car related things.

I believe that a high end sales tax is in order here.

This is not accurate. Parking revenues from street meters, permits and citatins make up less than 12% of PBOT’s budget (they make up 40% of General Transportation Revenues, and GTR is 29% of PBOT’s budget).

Reducing parking fees on street parking spots, which are visible and desirable, means they would turn over less often. Instant parkaging ‘shortage’!

There’s usually ample space in garages. We’ve had to close one of them already for lack of demand. One day I saw a sign outside a garage that said 316 and thought their clock was wrong. Then I realized it was the number of open spaces.

It’s also an “Oregon thing” that as long as PBOT and other transportation agencies have exclusive access to gas tax revenue, vehicle taxes, and parking fees, that such agencies will only be allowed to get that much funding and no more than that. In other states that combine revenue and allow for state and local gas taxes to be used for non-roadway facilities (such as schools and prisons), there tends to be far more money for streets during good years and less during recessions, since they also use income tax, sales tax, and other revenues for streets. Federal gas tax rules are of course the same in every state.

What would you cut from Portland’s budget in order to give more to PBOT?

I’d cut a bit from the ever-popular Fire Bureau for one, Parks & Rec as well. I’d move Maintenance permanently out of PBOT and into BES, since BES can use some of the sewer fees to cover some of the maintenance debt and they have long been a major funder of Maintenance. I’d also remove a bunch of unfunded unfilled positions at PBOT to reduce the need for layoffs.

So the guy from NC wants to cut OUR Parks budget? Come on David.

Given your medium income tax rate, no sales taxes, and a 1% limit on property taxes, you are never going to have enough revenue for all your wants unless you raise more revenue. So you’ll have to keep cutting your budget pretty much forever. If rent is the highest percentage for most people’s home budgets followed by transportation costs, should not local budgets also follow suit? More for housing food and transportation, less for entertainment, health, and security? Why do you need fire protection and swing sets if you are on the verge of losing your home and the ability to get to your job?

Time for a high end sales tax on sales over $1000

I’m curious, how can unfunded unfilled positions result in layoffs? Does PBOT have to put those open positions ahead of people on staff?

Too bad we don’t have the Buckman Pool and the police horses to kick around anymore.

PBOT has various positions they eventually intend to hire someone for, quite a lot of them. Some of the positions are for people who just left (retired or took a job elsewhere), others for upcoming capital projects, and some are place-holder positions in case a grant comes through. Although these positions are not currently actively funded, they still exist on the books in case they do get filled, in which case they will get funded. If you remove the positions, the negative impact will be that new positions will have to be created, which can be a political headache given a tight budget and an even tighter city council; but it will also reduce the budget footprint of PBOT, reduce the demand for revenue for unfilled positions, thus reducing the deficit at PBOT (making the pie slightly smaller).

Let’s say you like to travel to Amsterdam annually. It’s a lot of fun and you can do it for less than $5,000 per year. However, chances are you don’t do it every year – in fact, it may have been years since you last did it, further you may have never done so, but by gosh you would if you could afford it.

So you put into you annual budget, along with housing, food, bike repairs, and whatnot:

— Amsterdam Fund, $5,000

But then you think about all the other stuff you could do with $5,000. You could even forego using that $5,000 and reduce the size of your budget by that amount – your budget would be $5,000 smaller, would it not?

PBOT has a lot of these Amsterdam funds, or line items like it, that include material costs, personnel, supervision, overhead, and so on. Reduce those and you may go a long way towards reducing the annual budget crises at PBOT.

Thanks for the time that took. I guess there’s a similar process over at the PPB.

And they like to use them, literally, for that. You know, to see how things are going there, and bring back ideas for how PBOT can spend their money more responsibly.

Parking revenue is in the toilet, and gas tax revenue purchasing power has been eaten away by inflation. There may be other reasons as well, but these are the 2 big revenue streams.

Parking revenue and gas tax are not the 2 big revenue streams. They are both components of General Transportation Revenue, which makes up 29% of PBOT’s budget.

Gas tax is up for renewal soon. I have no sense for its prospects.

Parking revenue cratered due to pandemic-associated changes in consumption/work and the regressive gas tax failed to provide revenue stability (due to increasing CAFE requirements and EVs). The regressive gas tax was such a dumb tax and those who supported it over a stable progressive income tax should be deeply ashamed of themselves.

As I wrote above:

Parking revenue and gas tax are both components of General Transportation Revenue, which makes up only 29% of PBOT’s budget.

I agree with you that regressive gas taxes are not helpful. Progressive taxes on income, or more importantly on wealth and capital gains, would be a much better idea. However it seems they are harder to convince an already tax-averse public about.

Portland wasn’t tax adverse until recently. Something has changed.

Downtown is dead and people are driving electric cars and hybrids.

lots of factors.. Main ones are over-reliance for many years on gas tax and parking revenues.

I would like to know where this narrative comes from. PBOT’s budgets are not very easy to understand, but from what I can tell these income sources are not very large components. Still, if they drop dramatically then it will lower the budget. But there seem to be much bigger factors that are harder to pin down.

From PBOT’s budget:

28% (Other documents state 29%) General Transportation Revenues (inc. parking revenues and gas tax).

29% “Set Asides and Carry Overs” (????)

42 % “Other Sources”

taken from

https://www.portland.gov/transportation/budget/overview

It comes from the fact that you’re conflating capital project revenue with general revenue. As your own link points out 43% of PBOTs budget is restricted meaning they can only use it on specific projects. Those projects are never things like maintenance and street sweeping. So when the two main sources of their discretionary funding are drastically reduced PBOT doesn’t have money for general maintenance.

That’s what people mean when they say PBOT is low on money. As I point out below it’s a problem for almost all transportation departments and stems from the federal level.

I am aware of the point you make. To expand on it, the 72% of PBOT’s budget that is not GTR is all restricted. Even GTR has restrictions, eg. the 60% of GTR that is from the State Highway Fund (which includes gas tax) must be spent on “construction of roads, streets, and roadside rest areas” (though this can include bikeways).

Surely this suggests that the main problem is that most of PBOTs revenue is restricted (presumably by its state and federal sources)? To focus on the reduction in the scraps of money from gas tax and parking that are actually able to be used on maintenance seems to be missing the elephant in the room.

It’s an obvious point made in many places, but our current position is the result of decades of this type of funding, that encourages capital projects but gives no financial mechanism to maintain them.

Wasn’t the initial Max funding diverted from highways funding? I would like to know more about how that was possible.

Yup I agree but I don’t see it changing any time soon. We might be able to do it on a state level but considering how dysfunctional the federal government is I doubt there will be any major changes in how it funds road projects. I thought I heard talk about it when they were creating the infrastructure bill but from what I can find out it’s all for maintenance of other infrastructure not roads.

In my opinion there shouldn’t be anymore infrastructure expansion until DOTs can get what they have repaired. I’m sure lobbyists would strongly disagree. I mean there’s way more money to be made expanding freeways than there is to pave roads.

I agree with you about infrastructure expansion.

I doubt we can change federal and state regulations around restrictions, but I think it is important to be clear about what is limiting PBOT’s ability to maintain streets. The number of comments on this page stating falls in parking fees and gas tax as the biggest problems is disheartening. This is part of the same story told by the couple of people who have yelled at me from their cars about how I, on a bicycle, don’t pay for the streets.

It seems to me that a) car taxes and fees are not what paid to build the infrastructure in the first place and b) car taxes and fees are a portion of what pays for maintenance of infrastructure, but are nowhere near high enough to fund the amount of maintenance that people would like.

As mentioned by others, this is a combination of grants (federal, state, Metro, health, block grants, redevelopment, etc), some of which are typically carried over from previous years when projects take over a year, including the design and engineering phases (outer Powell Blvd for example), including projects that PBOT builds for other agencies such as ODOT and BES, PLUS the often needed “match” to receive those grants, typically 10% or 20% but increasingly 50% or even 80% local funding to get the grant. Until all the match is found, a project can’t even be started, so some of the match is accumulated. Related is the System Development Charges (SDC) funding which also tends to accumulate. Once the match is “found”, then a project is started, in which case PBOT (or rather the city) borrows all the funding needed through municipal bonds, and the debt is gradually paid off. PBOT has a lot of debt, mostly for paying for projects, but some of it is a portion of the city’s overall debt for pensions (Oregon PERS). Last I checked (in 2015) it was about 18% of the overall budget – not sure if this “Set Asides” or “Other Sources”.

This is chiefly the BES sewer cleaning contract. BES doesn’t have much in construction and maintenance equipment since both it and PBOT were split off from the City Dept of Public Works in 1988. During the divorce, PBOT got the maintenance department, which BES then hires out to do a lot of their “dirty work”. This contract can be as much as 30-40% of the overall PBOT budget. PBOT also does some work for other city agencies. I’m not sure where PBOT’s contribution to BDS goes, to help with staffing development review.

Thank you for all this information. Can you point me to any good sources of how to analyze and understand PBOT’s budget further? And I mean how to understand their budgeting categories and line items rather than the stories in their public announcements.

OK, the short answer is that multiple PBOT staff keep multiple spreadsheets about the various projects, costs, etc, but they don’t necessarily share them with each other and they often keep them away from the public. I could see some of them when I worked for PBOT as an intern (2000-2006) and saw others as a community advocate when I served on the PBOT Bureau Advisory Committee as the East Portland representative (2009-2015). The details varied.

The longer answer is that the number of volunteer transportation wonks in Portland is remarkably limited, about a half-dozen per district coalition, with 7 district coalitions (SWNI, SEUL, NWNW, NP, NECN, CNN, & EPCO/EPAP.) Each coalition eventually had one representative on the PBOT Bureau Advisory Committee, plus others on the ped, bike, and freight committees, plus various other reps (Parks, Planning, Police, etc). Eventually we all realized that each of us had certain specialized knowledge and that it might be a good idea for us to meet outside of our PBOT meetings and share info. At first it was just SWNI, SEUL, & EPAP who met monthly, but eventually the other coalitions joined in. We would share project info, funding sources, and so on, who to influence, who to ignore on city staff. If the city was prioritizing certain projects, they would send in the competent staff (April Bertelsen for example). If the city was deliberately trying to do nothing for an area, they sent in other utterly useless staff (we had a list of them.)

Some of us wonks were really good at memorizing our own regional projects, funding sources, and so on – myself for East Portland, Roger Averback for SWNI, and some others. Others were better at influencing those who needed to be influenced – Marianne Fitzgerald of SWNI, Linda Nettekoven of SEUL, and Arlene Kimura of East Portland are examples. So we would share info, then go through the PBOT 5-year budget line by line to figure out what we could move or manipulate down the road.

We would also look at budgets for TriMet, ODOT, Metro, Multnomah County, and the State of Oregon, as well as talk with our Metro councilors, County Commissioners and state legislators (there were 10 just for parts of East Portland – there’s a lot you can do with 10 state legislators.)

We also got into the habit of talking directly with city engineers. The nice thing about any engineer (versus say planners) is that when an engineer lies, it’s really really obvious, they are terrible liars, not at all convincing, and generally they mean well. So if you have an issue, talk with a PBOT engineer – the issue may not be their belly-wack, but chances are they’ll eventually pass it onto the person who is handling it. And since PBOT is an engineering-led agency (they ultimately hold the purse strings), it’s far more likely to actually get done.

More specifically, once revenue becomes set aside or tied to a project, is there any way to trace the source of that revenue back to its origin? Eg. state and metro grants – where does that money come from? Ultimately taxes? Which ones? And local funds to match grant funding – where does that come from? GTR? Some other PBOT category?

The money frequently shifts around.

Here is an example. In the TSP for ages was a $9 million (in year 2000 dollars) project to rebuild SE 136th Avenue from Division to Foster, roughly two miles, a neighborhood cut-through for drivers wanting to avoid 122nd, low-income low-density residential for the most part. The funding (according to the TSP) was to come from a combo of SDC and GTR. Basically the project went nowhere for decades.

In 2012 (or maybe 2011?) a five-year-old girl was killed running across 136th by a middle-aged female driver who was going the speed limit and who wasn’t impaired – the driver was not cited. However, for cynical PR purposes, the child was both cute and white, so there was lots of media coverage. At about the same time, the CRC was cancelled, in which ODOT was planning to spend $27 million annually for the next 30 years. So local state representative Shamia Fagen got the idea of moving some of that ready money toward 136th, even though the street is PBOT-owned and not ODOT. She got the other 9 East Portland legislators to support her, as well as move $22 million to outer Powell Blvd.

136th now had $3.5 million from the ODOT budget, not at all expected. PBOT then put in some SDC funding and some GTR, still far short of what was needed, but enough to start serious designing and engineering. A Metro grant then became available, then there was more from ODOT (for crossings, plus the Powell portion), a federal grant here, some other funding there, more SDC, and pretty soon (2014) they had $18 million and construction had started in earnest. Retaining walls were added, sidewalks put in, painted bike lanes, speed limit reduced, some parking removed, neighbors upset, etc.

Overall about half the funding was SDC and most of the rest was ODOT and not GTR. On a city street.

This sounds like complete chaos.

I had hoped there would be a way to analyze PBOT’s revenues to see what portion came from road user fees, from the local tax base (reportedly a very low amount), from SDCs, from other local sources, from state and federal levels.

Your account makes it sound like funding streams are wildly inconsistent, and even PBOT themselves may not know the amount of money spent on car-centric infrastructure that derives from motor vehicle user taxes and fees, or how much car-centric infrastructure is funded from taxes and fees that fall on non-motor vehicle users.

It’s not chaos, it’s intentional malfeasance.

.

https://www.oregonlive.com/commuting/2021/09/portland-auditor-says-transportation-bureau-failed-to-closely-track-gas-tax-spending.html

.

“The auditor found in 2019, and again Thursday, that the city hadn’t closely tracked how much money was spent on road repairs and how much was spent on pedestrian and bicycle improvements”

It’s not chaos, it’s just not GAAP either (generally accepted accounting principles). It stems from the way the feds have encouraged infrastructure agencies like Water, PBOT, and BES to budget based on a 7-year plan and funding cycle. Ultimately you can blame the very late Robert Moses of NYC who promoted this type of accounting (though it was invented much longer ago), it’s all part of what is known as deficit financing. I’m not sure how to explain it – it’s easier to do it graphically than in text – and only the mafia and highway engineers really know how to do it, but it’s been the norm for road projects since at least 1956.

The problem with this forum is that when you post stuff, the margins often shift, but let me try to explain the Moses budget method.

Let’s say Joe and his buddies at the Capitol have authorized a new program and PBOT has successfully submitted an application to build a $1.285 Billion elevated citywide bikeway with a new form of concrete that sequesters (stores) carbon dioxide, to create a carbon-negative transportation project. The money won’t come all at once, so the project is divided into 5 phases. For equity purposes, the project will start in East Portland (EP), then North & Northeast Portland (NE), then Downtown (CC, PBA made a stink), then Southwest (SW), and finally Southeast Uplift (SE). Once the funding comes in, it must be spent by the 7th year on each phase, which includes borrowing money, design, engineering, right-of-way acquisition, public outreach, construction, inspections, and finally submitting forms to get reimbursed by the feds:

(year – $millions)

20- 23. 24. 25. 26. 27. 28. 29. 30. 31. 32. 33. total

EP. 90. 80. 60. 5. 10. 20. 5. 0 0 0 0 270

NE. 0. 70. 80. 45. 5. 10. 5. 5. 0 0 0 220

CC. 0. 0. 90. 90. 80. 10. 5. 10. 10. 0 0 295

SW. 0. 0. 0. 90. 70. 60. 5. 20. 10. 5. 0 260

SE. 0. 0. 0. 0. 90. 50. 70. 5. 5. 10. 10. 240

Now let’s say in 2027 there is a really serious recession and PBOT has to cut staff by 25%, plus as usual downtown has cost overruns on the project and $80 million just ain’t enough.

20- 23. 24. 25. 26. 27. 28. 29. 30. 31. 32. 33. total

EP. 90. 80. 60. 5. 10. 20. 5. 0 0 0 0 270

NE. 0. 70. 80. 45. 5. 10. 5. 5. 0 0 0 220

CC. 0. 0. 90. 90. 80. 10. 5. 10. 10. 0 0 295

SW. 0. 0. 0. 90. 70. 60. 5. 20. 10. 5. 0 260

SE. 0. 0. 0. 0. 90. 50. 70. 5. 5. 10. 10. 240

In GAAP, $80 million is all you have, and you’ll just need to deal with cuts in the project, lay off personnel, value-engineer, and so on. But in the Moses method, you can “borrow” funds from the other phases, borrow from Peter to pay for Paul, as long as the money is paid back before either 7-year phase ends.

[I hope this works, even when I was writing this, the column margins kept shifting around.]

[Aww shit! Just saved it and the margins are completely off!]

Sorry David! You need a fixed-width font to get it aligned. But if someone is interested they can cut and paste your numbers into a file on their computer and clean it up.

No biggie. This is probably the wrong platform to try to explain this sort of thing anyway.

You keep saying this, but 28%, 14%, all the numbers you’ve mentioned in other comments, that represents a HUGE portion of the budget. That’s gigantic. I don’t know why you think something like parking which was slated to increase until Wheeler torpedoed that, and gas tax which has steadily decreased, would not have a major impact on them, especially if they were already in deficit.

I think the importance of parking revenues is being misinterpreted and overstated. Even before Covid and the disappearance of $80M in projected revenues from parking and the state highway fund, these revenues were never enough to pay for maintenance. Even before 2020 there was a 10 year PBOT maintenance backlog with a cost of billions. The maintenace backlog has now swollen to $4.4 billion. Even if parking and gas tax revenues had met projections, we would still be screwed.

The parking revenue loss is of course important, but there are much HUGER portions of the budget than parking revenues. The bigger problem is the hundreds of millions of dollars a year that are tied to building infrastructure projects (and paying off previous projects) that we cannot afford to maintain, because the sources of maintenance funding are so limited and paltry. Even before 2020, out system of user fees and taxes did not fund our infrastructure. We have been, and continue to be, building our way further and further off a cliff.

yes it’s much more complicated than my comment above! I’ll try to get together a PBOT budget 101 type of post soon.

But for now… A huuge chunk (“other sources”) is federal grants. PBOT gets a ton of federal/state grants for its work. They’ve become so reliant on outside sources as their slice of the General Fund has dwindled.

Set asides are things that can’t be touched and are allocated each year like ADA ramps. Not sure exactly what carry overs are but I’d assume that those are funds that were budgeted for one year and not spent, and so are “carried-over” to the next year.

The one thing I didn’t see mentioned is PBOT isn’t low on money for capital projects, which is like half their budget. Meaning they are free to keep expanding roads even though they can’t afford to maintain them. This is an ODOT problem as well. Pretty much every transportation department is experiencing this because States and the Feds won’t give money out for maintenance.

During periods of deep cuts, it’s standard practice at any DOT to build more crap in order to keep from laying-off well-paid (and expensively trained) engineering staff. People often ask why badly needed infrastructure projects are often delayed for years, even decades – now you now why, it’s to stave off mass layoffs during downturns.

And you are very right about maintenance – it’s one of the few things that Congressional Democrats and Republicans agree on – building expensive new infrastructure generates good paying jobs for their districts and helps them get re-elected; but maintenance is boring and just employs relatively menial low-paid laborers.

If PBOT can’t afford to do prescribed maintenance maybe it’s time to start closing streets. Maybe rotating (kind of like brown outs for electrical). Powell for the first week of the month, Burnside the next, etc. Think how much longer those streets would last without all the traffic on them!

Yes, building projects are great photo-ops for politicians. Maintenance, not so much.

There’s actually a really simple strategy that smart cities use to save big on street maintenance. They create a street hierarchy, something widely known as a functional transportation plan, whereby the strongest roads, those with steel-reinforced concrete road beds, have the widest lanes, fastest speed limits and are most attractive to car drivers; conversely, those streets where driving is actively discouraged have lots of proven traffic-calming features such as randomly parked cars and tree shade, but also usually have the weakest street beds (often just basic asphalt over a gravel base) and the slowest posted speed limits (or no signage at all.)

The streets in between, the collector, minor arterial, and neighborhood cut through, are spaced strategically so that traffic is discouraged on the weakest roadbeds by adding painted centerlines and edgelines – the narrower the travel lane, the slower the traffic in general, as long as there is a reasonable hierarchy of spaced streets (the stronger streets have more and faster traffic with wider lanes, the weaker streets narrower lanes and weaker roadbeds.) The really dumb cities try to make every street equally “slow”, which simply encourages faster (or more impatient) drivers to drive dangerously on streets we’d really rather they didn’t drive on at all, causing widespread degradation of streets that are expensive to fix (not to mention high losses of life).

Most streets are convex in profile – thicker and higher in the center to encourage runoff, thinner on the edges where the gutter or ditch is. Engineers use edgelines to discourage drivers from moving on the weakest part of the road and to drive as close to the strong center as possible, helping the road to last longer and require less maintenance and less costly repairs. From talking with my local city traffic engineers, 9 feet from the centerline to the edgeline encourages an actual 20-25 mph speed limit; 10 feet for 30-35 mph, and anything over 11 feet for 40 mph or more. For the space between the edgeline and the curb, they call a 7-foot space a “parking line” – and it is amazing how close to the curb car drivers will park when that line is there. Anything 6 feet or less they jokingly refer to as a “bike lane” – being engineers who only drive, they can’t imagine that anyone would be stupid enough to actually bicycle in such a narrow space totally unprotected from speeding cars – they certainly would never do so. They do point out, however, that so called “bike lanes” are great traffic-calming devices when used in conjunction with city bus service – the winning combo of bike lanes and city buses moving at the posted speed limit keeps faster cars from passing and helps the street to last longer.

Would this also ban lefts on reds onto one way streets?

It really is important for reports like this to be put together. It’s up to us to keep up the pressure on our state and local electeds to actually follow through.

Live your life however you want – but I will be sending some polite, concise, and firm emails to my representatives tonight telling them how strongly I feel about safe and sustainable streets in light of this report. Will one person saying something do anything? Probably not. A hundred? Maybe. A thousand? Hard for them to ignore.

Let’s be the squeaky wheel.

What is left out of the no right on red discussion is that it’s not only dangerous when people turn right on red. I would argue it’s even more dangerous when people rurn right on green (since people biking and walking don’t go straight on red). That’s because the red on right mentality means that people look to the left for other cars when turning, instead of to the right for people biking and walking like they do in Europe. So while I applaud the no right on red pilots as a good start, I think oly widespread changes and lots of education would change people’s driving behavior. The other problem is that people feel entitled to turn right no matter what and are impatient, use bikelanes as turn lanes etc. So at least that could be reduced in pilots. That is if car drivers even care about NROR signs. They don’t do where they are now.

I think that’s the role enforcement has to play. If someone is too stupid to read a “No Turn on Red” sign, they deserve an expensive ticket.

The only measure of success is a falling death toll. Everything else is just self-congratulation.

An easy way out is to simply re-classify many pedestrian deaths as suicides rather than as traffic deaths. Many jurisdictions (and some countries) already do this.

How does “rest on red” work with pedestrians? Do they get an instant crossing signal when they push the button? What if the perpendicular crossing already has a walk signal?

Could you press both buttons then cross diagonally?

Good thing this will be vigorously enforced!

It’d be nice to actually stripe some crosswalks and put 4-way stop signs too please. Both seem like a foreign concept even here in inner NE.

The news reports that the person killed on McLoughlin was struck in the southbound lanes near SE Cora St, where there are no sidewalks. It was dark. Walking on that road in the dark is a very poor choice, don’t blame the driver , blame the person walking in the dark on a road with high speed traffic. I myself have come close to hitting people walking in roads in the dark with dark clothing, when I was driving and even biking. Not all pedestrian deaths are the fault of drivers.

I am for right turn on red. I won’t turn if the sign says not to. I see people ignore those signs all the time. I also take advantage of free left turn on red from two way to one way roads every chance I get, but I make damn well sure nobody is coming before doing so.

Most are though. We probably shouldn’t be assigning blame to anyone without more information. Wearing dark clothing and walking on roads with insufficient infrastructure for pedestrians doesn’t make it the pedestrian’s fault. Sometimes people need to walk places that aren’t great for walking and you shouldn’t have to be lit up like a Christmas tree to expect drivers to see you. That’s what headlights are for which for some reason drivers frequently forget to turn on.

Instead of blaming the pedestrian trying to get to a destination, or the driver also trying to get to a destination, how about we blame the shoddy infrastructure? I drive this stretch every morning at 6am. I drive 55, and am regularly getting passed by vehicles traveling 60+ weaving in and out of lanes. The street lighting is poor in sections, the road surface is rough, and there is no protection for anyone outside of a vehicle. This is an urban freeway without the safety features required for a freeway, it’s designed to kill, and that is exactly the outcome we are seeing.

Good point. What is the old saying? – “Every system is perfectly optimized for the results it produces.”

So our transpo system is perfectly optimized to kill people, and that’s exactly what it is doing.

There actually are sidewalks on McLoughlin at SE Cora (in front of the old Ross Island building). There’s not yet a report, but I think the odds are pretty good that someone was walking across McLoughlin, even though it’s got a concrete barrier. McLoughlin is the closest we have to a surface freeway in the City, for sure.

Oh how I wished I owned the plastic bollard company. This town alone would me so rich.

The right-turn-on-red (RTOR) situation has become so confusing for drivers that I almost have sympathy for them in this situation.

The other day I was waiting at an intersection, on my bike in the bike lane, when a car came up from behind me and started to turn right, in front of me and across my lane, even though there was not only a red right-turn arrow but also a “No turn on red” sign displayed prominently next to the traffic signal!

I yelled “Stop!” and pointed to the sign and the red arrow above. The driver actually did stop and waited for the light so I could go straight, ahead of him, but it occurred to me that drivers have gotten so used to RTOR that they virtually assume they can do so everywhere. When I was learning to drive, eons ago, there was no RTOR and a red light meant STOP and that’s it. Red means stop and green means go: that’s probably what most drivers can handle.

Time for Oregon to go back to no RTOR and re-train drivers. I’ll bet the number of peds and cyclists killed and injured would drop precipitously.

PBOT just now thought of “rekindling” the relationship with PPB to stem traffic violence? That’s about 3 years overdue.

I’ve lived in the Pearl District 20 years and must disagree about traffic speeds purportedly down 71% — Excuse me, but no. Traffic is much worse today in my traffic marauded noisy place and many others within Portland borders.

Whatever PBOT does, deserving merit or not, is untrustworthy.

Since 2016, Wheeler has run a clown show.

“Oh yes let’s relocate I-5 under the Willamette River.

Waterfront condo towers,” said Wheeler knowing

this scam is neither possible nor advisable if it were.

Wheeler wants business buy-in on any Portland property.

Naomi Klein would call the problem Disaster Capitalism.