After extending the public outreach phase for their Lloyd to Woodlawn Neighborhood Greenway project last month, the Portland Bureau of Transportation says more listening is necessary to learn, “if and how the project can work for the Black community.”

As we reported in September, the project was called out in an article in The Skanner newspaper that reported outreach was, “slow to reach households of color.”

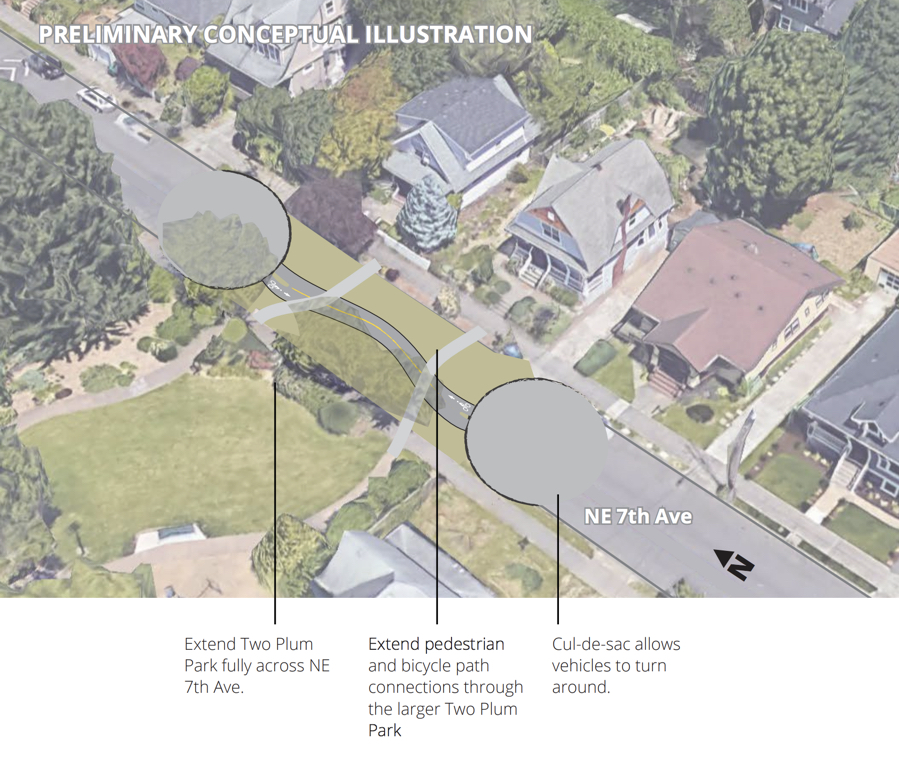

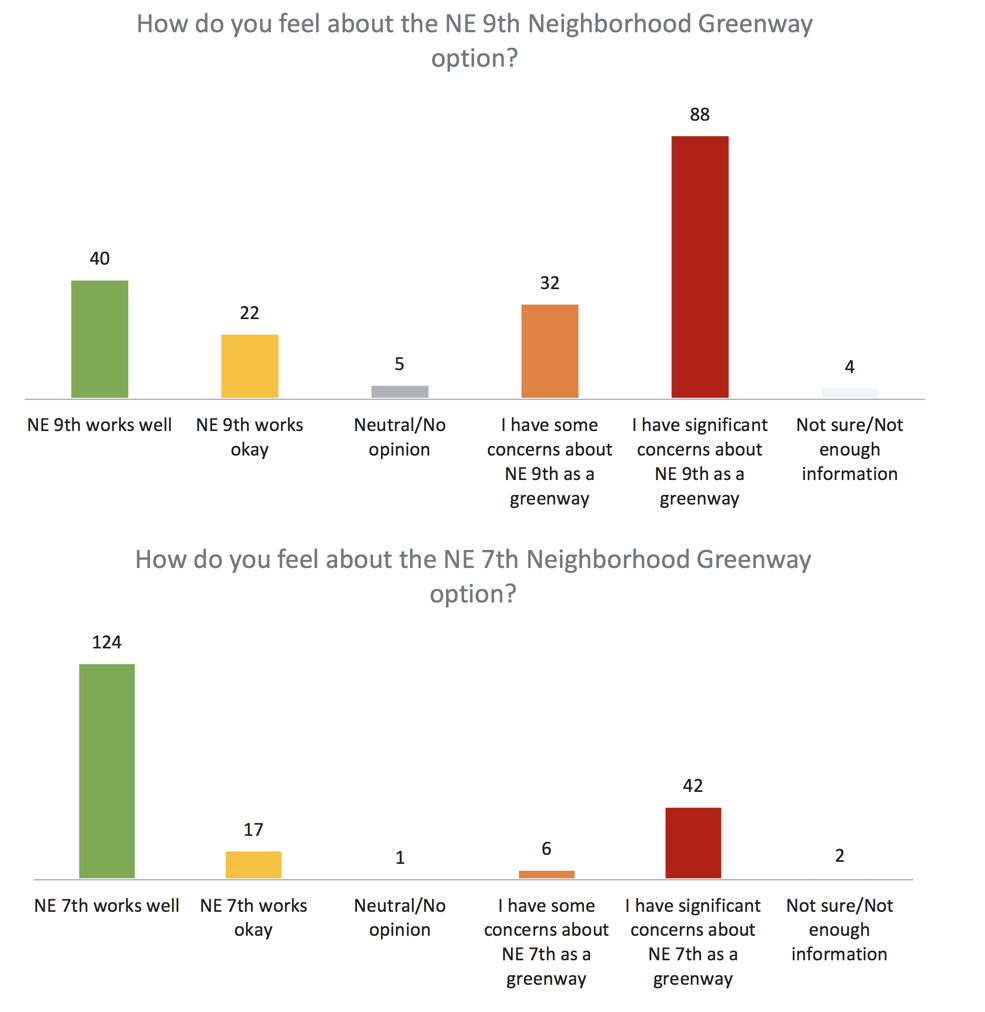

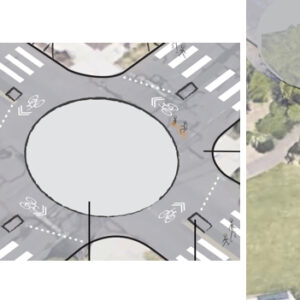

This project aims to create a low-stress, family-friendly bikeway that connects I-84 in the Lloyd to the north Portland neighborhood of Woodlawn. PBOT has shared two basic options — either using 7th or 9th avenue as the north-south route. Since the designs were first unveiled in July, a large majority of strong and enthusiastic support has emerged for the 7th Avenue alignment.

So far, all of PBOT outreach has shown that the NE 7th Avenue alignment is the overwhelming favorite. But that’s only if you measure by quantity of respondents. And as we’ve experienced in the past, it’s not just how many people speak up, it’s who speaks up.

PBOT’s latest stance on this project was explained in a letter from Senior Transportation Planner Nick Falbo that was published with a summary report of project feedback. This issue deserves clarity, so instead of explaining or paraphrasing PBOT’s letter, I’ve decided to share all of it below:

In July 2018, PBOT introduced two design concepts for a new neighborhood greenway street in Northeast Portland connecting the Lloyd and Woodlawn neighborhoods with route options primarily on either NE 7th Ave or NE 9th Ave. From July to September 2018, PBOT conducted outreach in the community to help make an informed and community-supported decision about where and how to build the new neighborhood greenway. After engaging with dozens of businesses and community organizations and hundreds of community members, the PBOT project team prepared the attached summary report to capture the themes, preferences and concerns raised about the project proposals to date.

The data misses what some community members – specifically the Black community – have told us about their concerns for this project.

At the August 1st Open House event, project staff heard from many Black community members who expressed strong concerns about the NE 7th Ave route option and raised larger concerns about how the benefits and burdens of the proposal for a new neighborhood greenway are distributed across Portlanders based on race, income and geography. There was high attendance of Black Portlanders that lived in the neighborhood and/or frequented neighborhood destinations (including schools, churches, social services and family homes) regularly. They engaged project staff to understand project goals and proposals and to express concerns about the NE 7th Ave route option. Many expressed that the street provided connectivity and accessibility and that prioritization of 7th for a neighborhood greenway would impact their travel patterns, but would not increase their travel options – which is also a central goal of the project. PBOT staff also heard concerns about how Black families have been burdened by transportation and other City investments for the “greater good” and that there was little confidence that their input could actually influence the future of this and other transportation projects.

The dialogue that occurred between and amongst PBOT staff and Black/ African American Portlanders was powerful, significant and has generated internal discussions about the City’s outreach strategies and planning processes. This moment has led to increased efforts to better understand the unique perspectives and priorities of Black Portlanders with connections to the Historic Albina community. Participants shared frustration about how information about the project had been previously disseminated and expressed concerns about the direction the project seemed to be going. Many community members view NE 7th Avenue as an arterial street for driving and as a crucial way to get around in a community they feel is less and less theirs; we heard concerns that making transformative changes to NE 7th Avenue will continue the decades-long trend of the City making changes for groups other than their own. Community members expressed the fear these changes could contribute to continued displacement of long-time community members from Northeast Portland.

We felt it was important to elevate this information because when the feedback from the in-person forum is combined with the responses from the Online Open House, some of the potency of messages we heard from this population can become diminished in this summarized format. While the summary report accurately describes the combined content heard in both in-person and online outreach efforts, we want to make it clear that the lessons learned at the in-person open house and the urgent need to better understand the perspectives of Black Portlanders will not be overlooked.

Advertisement

In response to these comments, PBOT extended the feedback period for the project design concepts from mid-August until the end of September 2018 to invite more participation. Since then, PBOT has broadened its engagement approach for this and other projects in North and Northeast Portland; PBOT has initiated a number of conversations and focus groups with Black/African American community members and organizations in the project area around what they feel the important transportation issues are in their communities. The intent of this expanded phase of engagement is to understand if and how the Lloyd to Woodlawn Neighborhood Greenway project can work for the Black community. No final decision will be made about the project route and design until after continued engagement with Black community members and organizations has occurred.

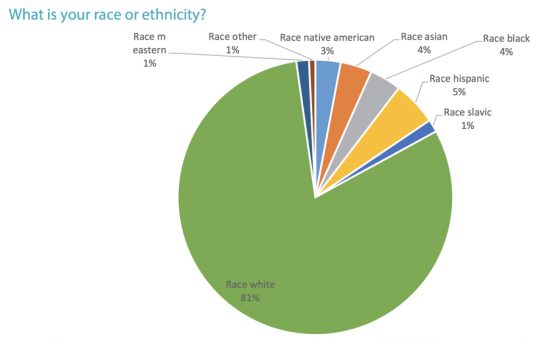

PBOT is making this decision in the context of neighborhoods that are the center of Portland’s black community (and historically even more so). Today 14 to 22 percent of the residents in the project corridor identify as black. Compare that to the percentage of respondents to PBOT’s online open house for this project. Of those 253 people, just four percent were black and 81 percent were white.

Five of the six letters PBOT included in their summary of comments publication voiced strong support for the 7th Avenue alignment. Those organizations include: Sabin Community Association, Northeast Coalition of Neighborhoods, the Eliot Neighborhood Association, and the Lloyd Community Association. PBOT’s own Bicycle Advisory Committee stated in an August 14th letter PBAC letter that, “The 7th Avenue Greenway alignment outperforms 9th Avenue in every measure that correlates to successful greenway design: safety, simplicity, intuitiveness, and cost efficiency.”

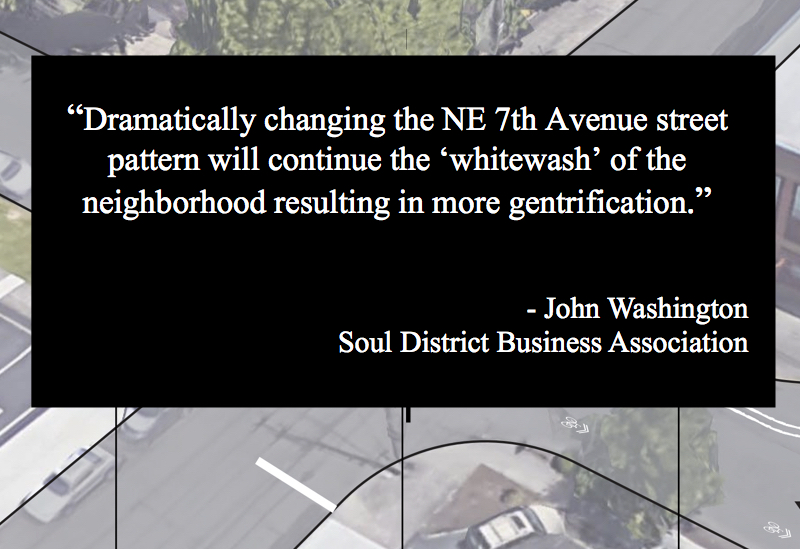

The one letter that opposed 7th Avenue came from the Soul District Business Association (formerly known as the Alberta Business Association). In their letter dated August 6th, Chair John Washington wrote, “We are concerned about the sincerity of PBOT to listen to our opposition to using NE 7th Avenue as a Greenway. We feel that the impact on our community of using 7th Avenue as a Greenway would perpetuate the negative effects of institutionalized racism and social engineering that has occurred in our African American neighborhoods and business community.”

Washington said they would rather see the greenway on 9th Avenue in part because, “We are deeply concerned that dramatically changing the NE 7th Avenue street pattern will continue the “whitewash” of the neighborhood resulting in more gentrification, as exemplified with the radical changes on Interstate Blvd., North Williams, and North Vancouver Avenues,” and that 9th will have, “Less impact to the street pattern, street use and street historical context, thus less gentrification.”

These concerns about how the project might change the neighborhood were echoed in comments left by some attendees of the open house and respondents to the online survey:

“I’ve spent my whole life in Woodlawn and every time y’all come in and change something it 1. raises the prices and forces my longstanding neighbors, friends, and family out and 2. makes the area more and more welcoming to the area’s new residents at the direct cost of the longstanding community. Please leave Woodlawn alone until you learn how to work with longstanding community members to address the actual set of problems we face. As things stand now, your projects are a barrage of neocolonial ‘development’ that — regardless of rhetoric or intent — pushes us out and destroys our community.”

“Again, getting into what, through my lifetime, has been a rich and white neighborhood and that is who these projects cater to and who they make comfortable so I’m sure they’ll love this minus a few NIMBYs who would be against you doing just about anything. NOTE: Prior to this if you were thinking this was from a NIMBY pov you would be wrong — I’m all for development that is wanted by the longstanding community that addresses historical inequalities and fixes or helps with structural problems that we face. What I don’t like is a bunch of neocolonial projects that, by design, destroy my community and our comfort in our home.”

“I want PBOT to prioritize and elevate feedback from the African American community on this decision. This community has been impacted by neighborhood improvements that have caused significant gentrification and displacement. I think that should be considered as a major factor in how feedback from different communities is weighed for the final design. I understand that there are significant concerns about the 7th Ave. option negatively impacting parents, caregivers and operations of the Albina Head Start program – these should be listened to and weighted in any greenway design decision.”

Projects that improve bicycling are no stranger to conversations about racism. How these concerns impact this specific greenway proposal remain to be seen. PBOT spokesperson Dylan Rivera said today that, “We are fully expecting to deliver a safety improvement project in this corridor.”

Kiel Johnson, a newcomer to the neighborhood who has worked hard raise awareness of the project, shares in a comment below that, “I think this is a good choice as long as there is a clear direction for this process will go in. My advice to PBOT is to make a clearly timed plan or you will lose the support that has been growing for this project.”

If you want to understand more about this topic, Dr. Adonia Lugo — author of Bicycle / Race — will be in Portland for a reading and discussion this Thursday (11/1).

— Jonathan Maus: (503) 706-8804, @jonathan_maus on Twitter and jonathan@bikeportland.org

Never miss a story. Sign-up for the daily BP Headlines email.

BikePortland needs your support.

Thanks for reading.

BikePortland has served this community with independent community journalism since 2005. We rely on subscriptions from readers like you to survive. Your financial support is vital in keeping this valuable resource alive and well.

Please subscribe today to strengthen and expand our work.

This is maddening. I saw the same pattern on the Williams St improvements. Compromises were made months late and the project suffered in the safety of ALL road users. Flyers are sent out asking for participation; for some reason this demographic ignores outreach and waits for the project to be in it’s final planning stages to derail it. Good citizenship requires paying attention and participating. Simply complaining and using race to poison the discussion is ineffective in obtaining a good outcome for all.

Our city is continuously growing and changing. Stopping change that benefits many people for the few is not the solution. I would be in favor of late outreach to address concerns of this project, however, just using it to derail hurts everyone. If there is historical injustice, there needs to be some effective way to address the grievances but simply trying to stop the city from growing is short sighted and lazy.

Hi Patrick B,

You sound like me back in 2011 when I covered the Williams project. I made some mistakes in how I covered and spoke about that project and I learned a lot from the experience.

I don’t think you can’t talk about what’s good “for all” if there are a number of people who don’t even see what you’re advocating for as a good — or who remain upset by past and current grievances. Especially when those people have deep ties to the neighborhood, have suffered from/still suffer from institutionalized racism, and have a cultural perspective that is very different than yours and mine.

I don’t think anyone is “stopping change.” What I hear is that people are concerned at the pace of change and the nature of the change. What you lament as compromises that made the Williams project “suffer,” are compromises I think made the Williams project possible.

And as you mention, there absolutely is historical injustice. And for some people those injustices remain. Racism is still very much a thing and I would argue it’s getting worse in the Trump era. We can’t act like it’s just in our history. We have to act with full knowledge that it exists today, that the planners and advocates in Portland are nearly all white, and that black people are still suffering from the consequences of discrimination.

I also think it’s extremely unfortunate that you’ve lobbed personal insults to people who are voicing their concerns. I don’t think that’s ever called for – no matter the circumstances.

Thanks for sharing your opinion. I hope you stay tuned and that you can be part of a productive and successful process going forward.

Referring to my use of “Lazy?” If so, I would say that it is more of a fact than a poorly used name to call. Effective citizenship requires early and frequent participation, and past problems are not a realistic excuse to opt out. To further my point–I think fighting this project is not addressing the gervence of past racist city planning. In fact, it may be alleviating the highway building neighborhood fragmentation and encouraging neighborhood (human connections) building. Increasing housing values is something that is happening independently–attacking a livability project like this is not effective in addressing past wrongs.

We disagree Patrick B. That’s fine. But if you want to continue to see your comments posted, please stop defending your use of the word “lazy” in this context. I hope you understand. Thank you.

Wow!

There was a process and they chose not to get involved at a time when there was an option to be a part of how things proceed.

At this stage in the game, I say ignore them.

Patrick B, your narrative of what occurred during the Williams process doesn’t sync with my own experience.

I don’t believe there were any compromises to safety made because of the input and valid concerns provided by the local black community throughout the entire process, but as a result of that input, PBOT added Rodney in addition to the Williams bikeway, and added a public art component to honor the neighborhood’s black history through public art. I was hoping we would see some wholesale changes to the way PBOT conducted public process throughout the city too. While PBOT may not be there yet, the letter from Project Manager Nick Falbo does remind me there are individuals within PBOT with the right approach.

If you have quibbles about the outcome of Williams, I suggest looking at Trimet who wouldn’t allow bus islands, and the initial project budget of a measly ~$500k for an entire corridor’s worth of improvements, both of which precluded a right-side-running bikeway.

Throughout the Williams Ave process we saw many bike advocates demonstrate their white fragility whenever race was brought up within the confines of a transportation project. Not here, not now, this is about bikes, etc. It has been gratifying to watch many within our predominantly white local bike advocacy community embrace intersectional work and come to terms their white privilege in the process.

I think the way PBOT is handling this one is absolutely the right move and is perhaps is the best demonstration of PBOT acting upon the lessons learned from the Williams process. Still, both PBOT and bike advocates have much more work to do.

You managed to use most of the key words progressives like to use, but you left out “Patriarchy”.

Gentle reminder that there are deep historical implications of white people calling black people lazy. It’s not okay. Like, ever.

Also, the folks from Soul District Business Association still proposed using NE 9th as a greenway—they’re not asking to scrap the project altogether. Yes, it’s an adjustment, but it’s not a roadblock.

Also, PBOT admits their outreach efforts didn’t garner input in a proportionate way, and (it seems) they’re trying to fix that.

Others mentioned the proposed I-5 expansion through a nearby neighborhood—also historically black—which would further compromise the air quality of Harriet Tubman Middle, recently reopened and championed by many black residents. Black people and many others are raising concerns about that expansion in regard to health and equity issues.

This population continually faces challenges to their well-being in Portland, and continually raises its voice in concern. Our city has the know-how and the means to adapt planning to best meet all its residents’ needs. It’s just a matter of will and effort.

Proportionate or disproportionate?

Should one group have more say than another?

Immediate residents should have more say.

I completely agree with you, Patrick B. This also reminds me of a few black activists a few years back protesting the planned Trader Joe’s on MLK (yet not protesting the Popeye’s, Pizza Hut, and other fast food restaurants prevalent on MLK). Whether its food options or transportation, City officials should make healthy planning choices to better serve our future and not pander to a few activists using the race card to prevent the progress of a good cause.

So you have no problem sitting in judgment of others’ decisions, preferences? Who are you to tell them that they should share your same ranking of businesses?

#Neocolonial.

This comment is full of dogwhistles.

This narrative is also inconsistent with my own understanding of the proposed Trader Joes and the development.

PAALF (Portland African American Leadership Forum) along with other neighborhood activists, including myself (a white guy btw), protested the millions in public subsidies going to prop up a commercial development in the rapidly gentrifying, formerly predominantly black neighborhood of Albina, and questioned why the money was not better spent on affordable housing in this context. Trader Joes, as they have in other places, expected the red carpet to be rolled out for them and did not seem interested in engaging in the conversation or pursuing a location there if there was any disagreement, so they took their toys and went home. Another grocery store took its place, and as a result of PAALF’s activism, PDC (Prosper Portland) came up with millions in additional money for affordable housing elsewhere in the area.

By your quick dismissal of this and strange focus on fast food restaurants, I question your intentions. You don’t seem to have a grasp of the neighborhood and the many years of activism from longtime residents around the development of their neighborhood and the many years of divestment and institutional racism employed by our city.

The disintegration of African American community in N and NE Portland was largely contributed to by the creation of freeways through those areas. Dangerous through traffic streets, including NE 7th, are a legacy of this destruction. Keeping 7th as an MLK bypass is maintaining the legacy of institutional racism in these neighborhoods.

I do not see the relevance in either statement and disagree with the first. Here is why:

I grew up in that neighborhood (born in 1979.) After the I5 was built in the 60s, the neighborhood was still predominately black. Big time. The freeway did far less to displace blacks in N/NE Portland than what has been done in the last 15-20 years. The biggest legacy I see of disintegration is Emanuel hospital (which occupies land my Father’s house once stood on), Cook Street Apartments/New Seasons (even though I love shopping there) on the corner of NE Cook where the hostess bakery/outlet store once stood, (I used to go there with my mom after school in the early 80s to buy bread and other goodies) the building across from it where Senn’s drive-in dairy used to be (used to pick a gallons of milk in a glass bottle…mid 80s), the red cross which is where my mother’s house used to stand, the large empty lots directly south of Dawson park, The Albert apartments across the street from Life change Church where the house of sound used to be and obviously the bike lane on Williams next to a string of cars stretching from just north of Fremont St. to south of Russell and further at times (even though I bike home on Williams Ave. daily, it’s a reminder nonetheless)…I could superfluously fill 2 pages with the rest of my list but I think this is plenty.

I do not believe many if any members of the black community will agree that “Keeping 7th as an MLK bypass is maintaining the legacy of institutional racism in these neighborhoods.” I can also say nobody in my family does. They feel quite the opposite.

The I-5 may not have led to displacement, but it did create air pollution which has effected the residents, especially children, that live in those neighborhoods. This was the intention, build in an area with lower political influence influence, where people can’t say no and for that matter can’t leave. N Williams and MLK developing into high car traffic streets that benefit the people who drive through those neighborhoods but don’t live in those neighborhoods has effected the ability for residents to walk safely or use non motorized transportation in those neighborhoods. Again, this effects children and the elderly the most. These negative effects devalued the property in these areas and in addition to targeting a vulnerable population, made it cheaper and easier for Legacy to take over land. This is institutionalized racism that is solidified in the built environment and continues to harm the people that live there.

Really not trying to troll or anything….

If all those things made real estate values tank then why is inner N/NE so expensive now? I lived in those neighborhoods my entire adult life starting in the mid/late 90s and when the desire to buy a home struck and I started looking there wasn’t *anything* affordable there. There wasn’t anything under 300k (my ceiling plus some) that wasn’t an absolute POS (basically tear down condition). So seriously, how is this? There are million dollar condos on Williams. I5 and it’s pollution still exist and there’s a hell of a lot more traffic and pollution on Williams/Vancouver now. So what am I missing? People that pay a million for a condo are dupes but there’s more to it than that.

A significant factor in the odd real estate prices in N/NE is actually property tax caps, believe it or not. A series of ballot measures in the 90s capped the amount a given site’s assessed value could increase to 3% per year, which happened to be at a time when much of N/NE was blighted by some very illegal mortgage lending practices that devalued large swathes of the area. Houses were worth very little, and since the max assessed value could only increase 3% per year from that initial value, many of them are still assessed as much under what they’re actually worth on the market for the purpose of calculating property tax. This doesn’t get uncapped at resale.

So many houses in the area have abnormally low property tax bills relative to the market value of the house. Why does this mean the house prices are higher? Because when you qualify for a mortgage, your cap is based off of how much monthly debt load the *total* cost of the mortgage will add to your current debt load – including property tax (which can be a significant portion). If the property tax portion is dramatically lower, you can qualify for a much higher mortgage payment with the bank at a given income level. People buying houses in N/NE can get larger mortgages for them than they could in an area with higher assessed values, so they can make higher offers for houses there than in other areas. This drives the sale prices up even faster than they’ve already increased in other areas, and here we are – crazy house prices in a neighborhood that doesn’t seem to warrant it.

Thanks, Daniel. I’m moderately familiar with the tax situation and was just discussing this with friends last week. One is a guy that owns very, very close in, since the 90s, and pays less in property taxes than I do out here (just east of 205) despite the high difference in the market value of our houses. This doesn’t stop him from complaining about it even though his house is loooong paid off. He pays utilities, property taxes and for groceries. Rough. Jerk (heh). I can’t imagine what it would be like to have no mortgage/rent payment.

I still don’t totally get why things that would lead to falling house prices for one demographic is no big deal to another. Thanks for the response, Daniel. I do appreciate it.

Property taxes on new construction are not at all lower in this area than they are anywhere else….. property tax levels on existing properties have nothing to do with the post-gentrification values in this area. Bikes, lattes, craft brews, boutiques and the proximity to downtown, however, certainly do.

Sure, but new construction is new construction – it’s expensive, and developers build it in order to get the highest sale price possible if they can. The question wasn’t why new stock was expensive, it’s why older houses, the kind that you might want to buy for a starter home, were *also* more expensive, and that is definitely related to suppressed property taxes.

To give an example, I bought a house in NE a few years ago. When shopping for a house in Portland, you don’t really know how large of a mortgage you can qualify for until you know which house you’re getting the mortgage on, because the possible swing in property tax burden is so large. Since the 2008 crash, these are hard and fast rules – nobody will issue a mortgage that exceeds a given debt-to-income ratio, because if they do they can’t resell the mortgage to Freddie/Fannie.

In my situation, the difference was stunning: I could qualify for almost $100,000 more in mortgage if it was for an assessment-capped house in NE, versus an identically-priced house in a neighborhood that made it through the 90s unscathed. Bikes and lattes had very little to do with my house’s purchase price. Here’s a map of property tax burden relative to real market value, note the wide swaths of blue in N/NE: https://projects.oregonlive.com/taxes/property/map/

Personally, I wish the ballot measures had been written to uncap on resale. I’d be paying more in property taxes, but under the current system I just end up paying more to the bank instead and I’d rather have the county get that money if I had a choice.

However, brand new houses are assessed at their full assessed value. And there are many, many million dollar homes that have been built or are under construction in the area that are being snapped up before construction even wraps up.

From the end of world war II untill the late 90’s the value of most homes was a multiple of the income of the people who would live there. Thus home values were fairly stable and affordable during this time ( even more so in a purposely marginalized part of town . But during the late 90’s the Fed, ( with the agreement of government and business) sought to improve the economy by boosting asset prices by lowering interest rates and pumping money in to the market. This caused house prices ( along with the stock market) to soar and people discovered N/NE Portland’s close proximity to downtown so prices soared there too. We had a hiccup with this asset “bubble” plan in 2008 but the Fed doubled down on lowering interest rates and pumping money in to the market and asset prices ( real estate) took off again. The forces of this growing real estate asset bubble are what have really caused the gentrification in North Portland and bikes are only token red herring to be blamed. The real answer to preserving the communities of N and NE Portland would have been to enact sweeping property tax and rent control laws back in the 1990’s. But I fear the real estate and development lobby would have been too powerful for that. I understand the feeling that Bike Lanes are some kind of talisman for gentrification, but in reality they are just one of the symptoms and not the disease.

In the 70s and 80s, banks were denying loans to blacks in certain areas of the city which contributed to the dismantling of the community. Here’s a good article on the racist history of Oregon and a lot of Portland as well.

https://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2016/07/racist-history-portland/492035/

So do you think that can be fixed?

It’s also worth noting that many former residents of the neighborhood still go to church, visit family and friends, use child care services, get haircuts or other personal services, go to community events, and other important activities in the neighborhood, and that’s if they had to move out to the numbers, biking is not really feasible, but their community in the Northeast 7th corridor needs them to be able to visit. In the skanner article one major concern was about the Head Start program at Fremont Avenue which I believe has no off-street parking and extremely limited on street parking or access. I can tell you is someone who bikes to the area with my kids to daycare in the area, it’s not easy and if I lived any further I don’t think it would be tenable. And people in Head Start are by definition short on money and short on time because poverty is extremely time-consuming.

People will still be able to drive to the neighborhood.

Are people unable to ride their bike on 7th?

People who can navigate speeding drivers that race them through traffic circles, that right hook without turn signals, and threaten them by passing at high speeds within less than a foot can ride their bikes on 7th. Also people who can ride over wet leaves covering fallen branches next to cars, and people who aren’t intimidated or too stressed out by aggressive drivers ride their bikes on 7th. This excludes most people ages 8 to 80. It excludes school age children. It often excludes the interested but concerned. But, Doug, you can ride your bike there and maybe that’s all that matters to you.

Thanks for the thoughtful replay instead of the normal and cavalier reply like “people can still drive there” comment. Those just get old and sound whiny. And if you call the worlds largest diverter something that can be driven over then maybe we should expect you to say something like your previous comment?

My partner is uwilling to ride on 7th. I suspect the majority of people who ride for transportation in Portland are unwilling to ride on 7th.

I didn’t say they wouldn’t, but accessing the Head Start might be more difficult unless those concerns about car access are taken into account. As someone with two toddlers who run in different directions away from me when I take them out of their carseats or bike seats, parents need to be able to get to that Head Start, and it is reasonable that a lot of them come by car for the reasons I explained above.

Hi Esther, despite accusations from other commenters, I wasn’t trying to be flippant or disregard your comment. I kept my comment short to avoid sounding overly argumentative.

I agree that there should be solutions to people getting to head start, possible solutions are mentioned by MaxD below, and could potentially make the child drop off situation safer and better than it is now. Dropping kids off on a high traffic street that is only going to get more congested over time unless it is protected is not a good plan.

It is important to understand that the choice isn’t make 7th a safe low traffic street or keep it the same. The choice is protect 7th from becoming much worse and provide safe access for diverse users or choose for it to become more congested and more dangerous.

https://www.theskanner.com/news/northwest/27340-new-greenway-in-ne-but-where

NE 7th is residential also.

This is incorrect. Almost the entire NE 7th alignment is zoned for multifamily or mixed use commercial.

Multifamily = residential = people live there and should be able to walk and cross the street safely. Most of NE 7th has people living directly on 7th.

If the zoning is different than the actual use, there will be gentrification.

I agree with Hello Kitty!

Blatantly false. Over 95% of NE 7th Ave (North of NE Broadway & South of NE Dekum) is zoned Residential (R2, R2.5, or R5) on both sides of the street. There is a small patch of Commercial (CM2) at NE Alberta for both NE 7th and NE 9th. And, the trouble area (NE Knott) consists of 3 parcels zoned Commercial (CM1).

https://www.portlandmaps.com/bps/zoning/#/map/

Please stop spreading lies that fit your narrative.

Sorry to diminish the joy of the moment, but I think HK is saying there will be gentrification regardless of implementing safety improvements on 7th or making it more congested with through traffic. I agree with HK too!

Yes — zoning changes incentivize redevelopment, which increases prices, which drives demographic change.

Craig, Actually we are both wrong. SE 7th is zoned R1 multifamily from Tilamook to Fremont on the South side with multiple lots of commercial zoning around Knott. From Fremont to Alberta it is zoned R2.5 and then around Alberta transitions into multiple blocks of mixed use commercial or multifamily zoning on both sides.

(The R2.5 color is very similar to the CM2 color so I mis-assigned several blocks.)

The NE 9th alignment is mostly R5, which is currently a single family house-only zone.

Also R2 is a multifamily housing zone.

Typo: R1=R2 is the lengthier post.

PBOT could add a curb extension at 7th and Fremont and block off the a half block along Fremont (west of 7th) as no parking/drop-off for Headstart. Cars could also turn south on to 7th from Fremont, drop off, and turn right on Ivy to get to MLK. The proposed safety improvements to 7th do not exclude cars, they only exclude cars from using 7th as a short-cut to avoid MLK or 15th.

Keep 7th Ave open to auto traffic, but speed bump the heck out of it. Make it where, yes, you can can drive, but 15 miles an hour or less… You know the speed bumps I’m talking about – the ones in parking lots, where you hit it and you’re like, “dang” can that speed bump get any bigger, rattles the whole car at 5 mph. A lot less people would use it.

Alternating one way stretches might also enhance multimodal use without without limiting access by residents and/or clients/customers.

Patrick, what you say may well be spot-on. However, I spent my high school years in a town (big town, 55,000) that was so white that when a friend shot and killed another friend one terrible Friday night, the local sheriff simply visited the three houses that had black male students who attended my high school. (All the witness knew was that the shooter attended my school and was a black male.) I don’t have data that far back, but it might have been 1% black and could have been lower.

All those things you mention as having gone by the wayside in your home neighborhood have also disappeared from mine, including that awesome dairy where we picked up the milk in bottles (after the other one stopped delivering the stuff), right across the street from the cool drive-in. However, I just looked up the latest census data and that town is now 12% black.

Things change. Lots of things change, often by large amounts. It’s hard to tease out causation from correlation in these complicated scenarios. Like I said, you may be absolutely right, but I’m not convinced by what you put on offer.

I’d say look at the number of blacks in N/NE Portland 1-5 years after the freeway. Then look at the number of blacks currently in N/NE Portland. How does the population count differ?

It’s clear that the freeway attracted a higher-income demographic, who displaced the lower-income residents who are in the area previously.

Surely you did not expect highway front property to stay cheap forever, did you?

** Close Lester; but you’ll have to try again if you want to read your comments here. I don’t appreciate the tone of your comments. – Jonathan **

Oh please Maus, all I did was parrot what a couple of the community members said. This project is so repulsive because all this city has done is crap on the black community and now Portland thinks it can make up for its sins of the past by building a bike path through the community to allow well off white folks to easily pass thru on their bikes.

First a freeway…now a bike greenway! Go green or go home! 😉

That’s interesting. I was unaware that the project is only for wealthy white people. I was under the impression anybody could use it.

Not a very perceptive comment. Gentrification is a real thing. And race is often not easily disentangled from its effects.

Do you accept the notion that bicycling is only for wealthy white people?

It is my belief that safe streets benefit everyone.

“It is my belief that safe streets benefit everyone.”

I would be inclined to think so too. But as this case demonstrates we might be mistaken; the framing, the perspective, the experience we bring to this question appears wholly different from the experience those who actually live there/used to live there/ feel ownership of that part of town. This gives me pause, and causes to me question my automatic endorsement of what we glibly call safe streets. If they don’t see a benefit or if the disbenefits they do see have greater salience than the traffic calming benefit we latch onto then isn’t it up to us (who by and large don’t live there) to listen, educate ourselves, try to understand?

This topic to me is one of the more fascinating ones I’ve encountered on bikeportland in years. Lots of threads seem to me to come together here, challenge our (largely white, largely fairly well off) preconceptions. This doesn’t happen too often in such a condensed fashion.

I will add that unlike the Lincoln diverter brouhaha, where the situation seemed to me rather easier to understand (younger(?) bike-ier folk vs older (white?) homeowner, auto-ier folk), this one seems (to me) vastly more complex, nuanced, difficult to quickly grasp. The difference, obviously, has everything to do with race and income and sway with city government. I don’t feel particularly beholden to the well off homeowners on Mt. Tabor who have had it pretty good for a century+, and who may resent a diverter or loss of onstreet parking, but I do feel that we as a society, a city have so consistently screwed up and biased our treatment of this demographic that any bike/auto, safe/unsafe binaries we may have at the ready should take a back seat until we’ve sorted out who’s not been heard here.

And you would be OK if that resulted in a continued dominance of automobility in this area, if those who have not been heard so desire?

That may be the result, or we may learn that the way we appreciate, understand, conceptualize this situation is incomplete. I’m open to learning something from this which I expect could be more valuable than scoring another point against automobility.

I’m also open to the possibility that just as we are unable to understand what some folks in this community are saying, they also may not be understanding us. So sitting down, finding a way to hear the other could, conceivably, lead to outcomes neither of us currently see or can imagine. You seem determined to see this as zero sum: one party loses. I’m not so sure.

I have been a long and consistent advocate for sitting down, hearing “the other,” and looking for mutually acceptable and creative solutions.

I never see these situations as zero-sum; I believe there are often ways to make things better for multiple constituencies simultaneously, and I believe I’ve said this frequently and consistently. It is others who have argued against this view.

I am happy to welcome you to the fold.

“I never see these situations as zero-sum”

That is easy to toss out—and good to hear—but you must realize that your statement to which I was responding certainly suggests this to be zero-sum.

While you may in your heart be open to mutually beneficial outcomes, your words typed into the bikeportland comments often give a decidedly different impression. And those are what I have access to.

It’s not about who gets to use it. Its how it was planned and built in the first place. People know when they’ve been ignored and forgotten in the name of “progress”. As an east Portland resident I know that feeling all too well. And I consider myself fortunate compared to the folks who’ve been displaced from inner NE.

Has the group involved presented their own plan for improving the neighborhood and correcting the effects of decades of racism? All I see is “do it somewhere else, we want our neighborhood to stay like it is…which we are also complaining about because of past racism”. I just legitimately don’t know how things are realistically improved in their opinions… keeping housing costs low? Keeping demographics primarily minority? Not bad things maybe but realistic within current landscape of the cities growth? What positive improvements/changes can they demand? Cause changes are happening regardless…

Shouldn’t it be up to residents whether their neighborhood needs to be “improved”?

That’s what the people on Lincoln and 50th said about that diverter. The answer was a resounding no cause the streets belong to everyone not just the property owners lining it. I’m not saying their input shouldn’t be considered or even weighted more then someone who just occasionally commutes through the area but in the end if we designed all streets based on the surrounding neighbors desires it would be a chaotic mess.

This may well be true. Take SE 26th, for example; if residents had their way, it would be a bit more chaotic and much slower to drive on, perhaps less hospitable to heavy trucks. It would be safer and more pleasant for cyclists and pedestrians. Luckily, the city is keeping the chaos at bay, and with an eye out for the larger good, is removing the bike lanes.

Well that’s an interesting twist. I’m not sure why you brought up 26th except to maybe win some argument you had with someone else about removing the bike lane or distract from the conversation. I also thought the City was opposed to removing the lane but ODOT was insisting on it. I also question your claim that having bikes take the lane is less chaotic. Also how is having a wider road we know causes people to speed less chaotic? They’re just speeding so they can stop sooner at the timed light anyway. The final irony is removing the lane is doing the opposite of what is proposed on 7th making it a more habitable area for all road users instead of just one on a street that is mostly residential.

I mentioned it because it’s a counter example to the idea that we’re always better off with planners making the decisions rather than local residents, which seems to be what you were arguing for by introducing 50th & Lincoln. If locals had their way with 26th, I’m pretty sure the street would be a lot more friendly from a cycling perspective than it will be. This is true whether you lay the blame with ODOT or PBOT or some combination thereof.

I wasn’t’ suggesting “we’re always better off with planners making the decisions” those are your words. I was responding to your suggestion that “it be up to residents whether their neighborhood needs to be “improved”” So to be clear. No I don’t think it should be up to residents whether their neighborhood streets are improved. Those streets are for everyone. And as I said before I’m not saying their input shouldn’t be considered or even weighted more then someone who commutes through.

I brought up 50th as an example where there were concessions made to the neighbors like turning right onto Lincoln from 50th but the entire project wasn’t just scraped because some residents didn’t want it at all.

Guess what, someone buys a property there they are now a resident and if they want to develop the land and build higher cost housing or retail that is up to them as a resident so other residents would support that right? As I said, change is happening regardless, either demand the change happens in a way that benefits your interests or understand that you will soon be lamenting that you lost something without getting anything in return.

You’d have to ask them. I’m guessing that most people would weight the benefits and external costs the project imposes on them. Though I might differ in your characterization of an absentee property owner/developer as a “resident”.

Well stated. It seems like this kind of involvement simply becomes a platform for bringing up past issues that there is still resentment about. I seldom hear actual solutions.

According to Wikipedia: The 2010 census reported Portland as 76.1% White (444,254 people), 7.1% Asian (41,448), 6.3% Black or African American (36,778), 1.0% Native American (5,838), 0.5% Pacific Islander (2,919), 4.7% belonging to two or more racial groups (24,437) and 5.0% from other races (28,987). 9.4% were Hispanic or Latino, of any race (54,840). Whites not of Hispanic origin made up 72.2% of the total population.

Based on the above stats which are approaching 9 years out of date the data in the responses to the outreach whites are over-represented by 5%, Asians under-represented by 3%, Blacks under-represented by 2%, Native Americans over-represented by 2%, and Hispanics under-represented by 4%.

Would a project on 7th Avenue reduce the legacy of institutional racism? Would it matter if that area were now predominantly inhabited by white people?

Nesting fail.

Should it? Could it?

The article states that, “…14 to 22 percent of the residents in the project corridor identify as black.” I believe you’re interpretation of the statistics may be wrong.

I’m not going to do it (at least not tonight), but one can go to the American Community Survey and look at the 2016 five-year rolling average for the census tracts that contain/border the project and get the racial make-up of the corridor.

It would probably be a good idea to compare that to the city as a whole (the numbers cited above are a bit out of date, as mentioned). Here’s what’s there for PDX at the household level:

White (non-Hispanic): 77.8%

Asian: 5.9%

Black: 5.2%

Hispanic:/Latino: 6.9%

Native American/Hawaiian/Pac Island: 1%

Multiple: 3.7%

Other: 1.8%

Note: it doesn’t add up to 100% because of the weirdness of Hispanic/Latino and white. White and Hispanic added together should be 82.4%, but when broken out end up totaling higher for some reason. That’s the problem with mixing race and ethnicity, I guess.

Dang, and all I want to do is ride my bike in any neighborhood that appeals to me or lies between my points A and B. Community resources get complicated in a hurry, what with having to involve the entire community and our history/present inequities.

Do those who oppose public outreach on bike projects, is this another example of “too much process”?

I think it’s a misunderstanding of the process. The city wants to hear your concerns. But don’t expect them to do anything about them. Just because they want to hear you doesn’t mean they’ll take action on your concerns. Sometimes there’s something that somebody brings up that does require action, but it’s not often.

N Williams, version 2. Why would anyone not want safer streets in their community?

What’s being proposed is the opposite of pushing a new freeway through the community. I don’t understand the pushback.

Listening is job#1.

Not understanding is fine, but stomping your feet in frustration, and implying that your inability to understand is someone else’s fault is not fine.

There was no blame or vitriol in my comments above. I was asking a sincere question and stated that I didn’t understand the opposition to the proposed project. No foot stomping involved.

The question you asked is a very uncomfortable one for many people, which is why you’ll never get a straight answer from them.

What do you do if you are a strong advocate for active transportation, and also for elevating voices that have historically been ignored, and those voices you seek to

elevate speak in opposition to active transportation?

“I didn’t understand the opposition to the proposed project”

I think the opposition has stated its case (with respect both to process and result). Your view of the result as an unambiguously ‘safer street’ doesn’t necessarily align with what someone else who has a different perspective, a different experience of this sort of thing, who’s been left holding the short end of the stick a few too many times sees, anticipates, fears.

My response to you above arose from my sense that you were more interested in asserting that their perspective didn’t make sense/ was absurd rather than expressing genuine interest, showing yourself eager to understand where they are coming from, being open to learning potentially uncomfortable new things.

I don’t know… “safer” seems a rather objective measure. It’s not culturally ambiguous.

Where you do see a cultural difference is on the tradeoff between automobility and safety/access for other modes; this is the same difference you have been slow to acknowledge in similar arguments in other parts of the city (east of 82nd, for example). Either that tradeoff is an absolute or it is situational. It can’t be both.

*You* see the tradeoff as “between automobility and safety/access for other modes,” what I’m trying to suggest is that this binary may not line up with the way these long-abused residents may see things, and to the extent I’m right about that it matters _because_ these residents have for all intents and purposes never been listened to, respected.

I do however see your phrase as a useful binary in other parts of town where I think I understand the history better; here I’m much less sure of myself, am more inclined to let those who feel marginalized speak for themselves.

“Either that tradeoff is an absolute or it is situational. It can’t be both.”

I’m not understanding.

It is complicated, I admit that. Full disclosure, I’m a middle-aged white male, but I’m aware that bestows privilege that affects my perspective on the world. I can’t change the situation I was born into, but I can strive to acknowledge my privilege and try to understand the perspective of others who have historically been oppressed.

I know that, as a society, we have failed miserably to eliminate all forms of discrimination. I am also familiar with the history of Portland’s racism and the grossly unfair decisions that have affected communities of color, especially in this part of town.

I am fortunate enough to be healthy and live close to my work, so that I can do my daily traveling by bike, foot or bus, and I am grateful for it every day. Our cities have prioritized motor travel for fifty years or more, and it’s not easy to just switch over to active transport when the hard infrastructure challenges it.

The fact is that automobility it ruining the planet and killing us all. Nearly every day, I read a new article that states that climate change is happening much faster than we thought. Shorter term, people driving cars manage to kill nearly 40,000 of us in the US alone, and many, many more have injuries significant enough to change their lives. We can’t get cars off the road soon enough.

Which is the right choice – allow historically oppressed communities to dictate that we limit changes to their neighborhood, or make the changes that *all of humanity* needs?

“Which is the right choice – allow historically oppressed communities to dictate that we limit changes to their neighborhood, or make the changes that *all of humanity* needs?”

On virtually all other bikeportland stories I’d unequivocally agree with you that it would be the latter. In this case, though—and I find this fascinating—I am not sure that the framing you and I share is the same one that those in question here would bring to the table. Once we’ve heard their perspective, their alternate interpretation, how they see the tradeoffs, and not before would I be willing to bring my/your choice to bear.

And I am open to learning that what to you and me seemed so obvious for all these other situations may not be once we’ve heard these folks out.

I very much agree that a great injustice was done when I5 went through these neighborhoods in addition to the blocks that were cleared and demolished for Emmanuel Hospital and its surround parking blocks. I would be in favor of doing the right thing and reversing these tragic decisions by blocking and filling I5 back in and offering all the land created preferentially to members of the traditional community on a subsidized basis, ( after all happy motoring is on its last legs and climate change needs addressing so lets make a bold move). Lets also demo the hospital and return the land to its original residents. I think our health dollars would be better spent setting up Cuban style neighborhood clinics all over town. Fighting over bike lanes is just a proxy battle for the real issues. Climate change is upon us, Our health care system is the worst and most expensive in the world and the people of a great neighborhood in Portland were ripped off let fix it all in one fell swoop that shows we are still a great people and a great city.

Comment of the week.

And a bike lane that helps displace more car-dependent people to the outskirts in favor of more healthy, climate-minded people who drive to the coast or Mt. Hood every weekend will have absolutely no net benefit to either climate change or health. But keep believing that gentrification is helping.

It’s not the worst in the world…c’mon.

I think this is a good choice as long as there is a clear direction for this process will go in. I was recently watching the streetsfilm for super blocks in barcelona (closing off entire neighborhoods to cars) and was struck that one of the advocates said that they were comforted that neighborhoods were being choosen partly because they had rent control to limit displacement.

What if PBOT used some of the road way and built affordable housing on it? Using that as a diverter? Or provided some system development excemptions to encourage more affordable housing on 7th? Or started loaning out affordable electric cargo bike and tricycles to people living nearby?

My advice to PBOT is to make a clearly timed plan or you will lose the support that has been growing for this project.

How to get things done in Portland, attach a dream about housing to it. Meanwhile we are still building empty buildings and offering $500 amazon gift cards for people to move in who don’t currently live in Oregon. Dangling the carrot until they are forced to submit is not a good reason for a greenway.

I disagree strongly with the statement that “this demographic” ignores outreach. In the case, it’s clear that PBOT staff didn’t do appropriate outreach; they didn’t learn their lesson from Williams!

I’m seeing a really paternalistic attitude from some commenters here, which feels quite a bit like the Williams Ave conversation years back. Depressingly so.

There seems to be this sense that, because (predominantly white) planners and (predominantly white) active transportation activists have designed a project that is “good” based on commenters’ criteria for “good” projects, that the Black community is obligated to feel the same way. Or, if Black folks don’t support the project, then they’re obligated to accept it because the (predominantly white) majority has decided it’s the right thing to do.

This is disturbing. As one of the public forum attendees says, it’s a fundamentally colonial attitude toward a community which has been disproportionately burdened by racism, gentrification, displacement, and “urban renewal” projects. It participates in the time-honored tradition that Matt Hern calls the “Portland Achievement” in his book, What a City is For:

“The more I study Portland, the more I encounter this particular civic strategy of power: liberal affirmations of tolerance, sincere apologies for historical traumas, listening sessions, broad mandates for consultation, and effusive evocations of solidarity, followed up with resolute inaction, re-entrenchment of white privilege, and business as usual. It’s a common strategy pretty much everywhere, but Portland has perfected it as a fine art. I suggest that this strategy henceforth be name the Portland achievement – the broadly branded maintenance of a liberal reputation despite compelling evidence to the contrary.”

Yes, I-5 did an incredible amount of harm to the Black community in North and Northeast Portland. Yes, the construction of Legacy Emanuel did the same – hell, there are some blocks where Black-owned houses stood that are STILL Legacy-owned empty fields today. But the solution to those historical injustices is not to ram a project down the community’s throat because it’s “good for them.” It’s to create deeply democratic, authentic public engagement processes that give ALL communities a chance to weigh in on what they’d like their neighborhoods to look like.

It sounds like that’s what PBOT’s doing. I’m overwhelmingly skeptical of the quality of city public engagement processes based on 10 years of experience navigating and participating in them. But hell, this is a step in the right direction.

Thanks for your words, comrade.

The concerns about gentrification have been weighing heavily on me. I am now persuaded that the proposed 7th alignment is problematic. I look forward to seeing the outcome of a public engagement process that emphasizes input from all communities.

Nicely stated, thank you!

*My vote for comment of the week*

Just want to say I’m excited to see two people in this thread have tagged comments with “comment of the week”! Thank you! Makes finding one to feature so much easier.

To be honest just reading the reporting above and the basis for concerns surrounding this the only conclusion I came to: NIMBY’s are NIMBY’s no matter their race.

The different between white and black is just the power with which they can resist these improvements. So it sounds like goal of prolonging the engagement period here is to give the black community the same opportunity to stop changes and complain about transportation improvements that are usually afforded to white neighborhoods…?

I believe the goal of extending the process is a good faith attempt by the city to facilitate meaningful input and contributions to this project from residents who would like to be a part of that process. I think it’s a very smart and encouraging move by PBOT.

I haven’t seen any evidence that the majority of the black community is opposed to the project. What I have seen is oversimplification of the black community, which like most communities has diverse needs and is complex. This is mostly due to easy headlines and lack of depth in understanding. However, like Williams, a few individuals with a vested interest in the status quo and maintaining car traffic speak out and claim to represent the entire community.

Most of the historic black community left Central Portland before 2010. Many moved to East Portland, but most moved out of the city altogether. I’ve even met some “Portland blacks” here in Greensboro, well-educated, west-coast dialect, very liberal, usually working at one of our local food coops.

Portland follows a classic disinvestment-cycle policy: 50 years of disinvestment and neglect of Albina followed by “White Lining” (literally, painting white bike lanes) and re-investment by the city (MAX Yellow Line), followed by gentrification by wealthier younger folks (mostly white, but also Asian and even middle-class black), leading to a nearly complete displacement of the original black community. The same pattern has been observed in every other US city of any size, but it’s especially glaring in Portland and DC.

Given that “people of color” includes the vast majority of humanity (representing more than 75% of the world’s population), I don’t know how any group could credibly claim to represent them, any more than any group could claim to represent people of European descent.

People can (and should) speak for themselves.

We’re talking about POC with roots and ties to a particular place….. something nomadic millennials who have actively chosen to relocate the whitest city in America might not understand.

Why should they care?

Who?

Your proclivity to be terse sometimes interferes with your audience’s ability to follow.

I strongly believe that the residents most impacted by this (or any) project should have an outsized voice in shaping it. I strongly believe that race is not what gives those voices legitimacy.

Good coverage! Thanks.

Personally, I don’t see a strong case that a 7th Ave route would have different effects on housing prices or cultural stability than a 9th Ave route would. (I’m a white guy who doesn’t live or work in the area, though I come through it regularly.) Personally, I do see a strong case that 7th is a better route for making biking useful to people who travel through this area, and also that a 7th Ave route would do more to disrupt people who are committed to driving through the area.

I think all of us humans have a strong tendency to take political positions based on our cultural affinity for those on one side or the other. I think the main antidote to this tendency is to find other affinities that crosscut or bridge those cultural divides.

This is hard.

The 7th route is adjacent to multifamily-zoned lots while the 9th option is adjacent to lots that are mostly zoned for single family residence. IMO, this makes for a huge difference in the gentrification potential between the two routes.

Maintaining and allowing the increase in high car traffic on a residential street is not a good solution for gentrification.

I believe that one can be anti-gentrification and pro-alternative transportation. I reject the idea that this relationship is a zero sum game.

Me too. Thats why I think advocating that people of lower SES should be exposed to greater health risk to prevent gentrification perpetuates inequity.

You do realize that no decisions have been made. This is a process, and a necessary one, ATMO.

Yes, and I agree that the process is necessary and very valuable, but the discussion in these comments includes the evaluation of the project, specifically, and a general discussion of how and when to designate streets as high car-traffic streets or to improve access to people who travel on or inhabit those those streets without cars.

I see this post as well as the discussion in the comments as part of the process.

Soren, what’s the most persuasive evidence you’ve seen that being located on a neighborhood greenway affects a home’s price? I have yet to see any that shows any measurable effect, in Portland or elsewhere.

There is a “correlation” between bike infrastructure density and real estate values. The causality may be difficult to prove but I think the perception matters regardless when it comes to our decision making process.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2016/01/14/why-bike-lanes-are-hugely-unpopular-in-some-neighborhoods/?utm_term=.563846842a4a

Some of the most convincing evidence that for causality comes from the aggressive use of walk and bike scores to market real estate development. (Both bike and walk scores correlate with increased real estate/land value – https://www.walkscore.com/bike-score-methodology.shtml).

I believe you wrote about this phenomenon as well:

https://peopleforbikes.org/blog/analytics-for-cities-why-bike-score-rankings-actually-matter/

“…Walk Score established itself as an imperfect but useful way to capture walkable urbanism, the hottest surviving commodity in the housing business.

Real estate agents across the country have embraced Walk Score for a reason: it helps them make money. A 2009 study concluded that each point of Walk Score correlated to a sale price difference of $700 to $3,000.”

I look forward to seeing how this expanded engagement goes and am hopeful that the process will result in something that both active transportation supporters and people who have raised concerns about gentrification can call a win.

There’s great evidence that Walk Score matters in a causal way, though Walk Score is unique as a transportation metric exactly because it looks at destinations rather than infrastructure, and there’s lots of other literature about the amenity value of nearby destinations. Nothing I’ve seen to show Bike Score (mostly about infrastructure used by a far far smaller share of the population) does.

In any case, I agree perceptions matter in their own right.

Initially I thought it sounded like a good plan, but the more I think about it this feels like a very self-serving project for the mostly white cycling community. No wonder people in the African-American community feel apprehensive. Too many bridges have been burned.

Metro cites data suggesting that “people of color” are slightly more likely to walk or bike in its 2016 regional transportation snapshot. However, this data is dated and homogenizes black people into a larger category.

https://www.oregonmetro.gov/news/you-are-here-snapshot-how-portland-region-gets-around

I find this sort of homogenization to be a form of “othering”.

Cars are the most important people so we’ll let cars use all of the streets while we talk about how best to build something eventually, maybe. I’m fine if everyone gets a say in how it should work as long as they would feel safe letting their 8yo kid or 80yo grandparent ride there. And ASAP. We need to have every street in the city be a place where normal people feel welcome on bikes, not this secret sparse labyrinth of greenways where “the cycling cyclist community” can sneak around on a bike and not interfere with any cars doing important car stuff.

Last time I checked, black children deserve safe streets just as much as white children.

Crosswalk Cathy is very relevant to this discussion:

https://www.portlandmercury.com/blogtown/2018/10/30/24136789/white-woman-calls-cops-on-black-mans-parking-job?

It’s clear from the video that the back tire was fully into the curb cut area so the back bumper had to be more than a few feet into the sidewalk, making it hazardous for people to cross there. It looks like a diagonal apron, but that’s still some car-culture entitlement parking, which has nothing to do with race. “The video doesn’t show much of the car, but it’s clearly sticking out an inch or two in front of a curb where a crosswalk begins.”

Everyone could have handled it better but the problem is still cars. If they live in the neighborhood, why did they need a car to pickup some food?

And the driver’s car was (reportedly) blocking a crosswalk, which is uncool regardless of race.

Confirmation bias for people who see racism everywhere.

Would you feel that way if the driver were an “entitled” white BMW driver?

I concur.

“Now, could she have hung up the phone at that point and said what they did was not cool? Yup!”

Bingo.

And this is how I feel about the NE 7th project. It’s time to hang up the aggressive advocacy and say that we are willing to listen, to discuss this further with underrepresented members of our community.

We should always be listening to the community.

Should she have treated them differently because of their race (which I am told does not exist)?

Given the pervasive pattern of racism (institutionalized and otherwise) I think the onus is on those who want us to think a given behavior is not racist to demonstrate that, persuade us, not the other way around.

On an utterly unrelated topic, what is going on in the banner image at the top of this page? It looks like a cyclist is forcing his way through a crossing that appears well occupied. Or is that just a trick of perspective? And why are people crossing three car lengths past the intersection?

Inquiring minds want to know.

The sins of the majority white in the past, in this case the freeway rolling through the poor black neighborhoods, comes back to haunt Portland and Oregon. Until the debts are paid, there will be trouble until this generation passes on.

Who owes a debt to whom? Were property owners unfairly compensated?

Oh yeah, they were totally fairly compensated. Just like women in the workplace. Or sharecroppers. Or…you get the picture.

Probably not best to whitewash this one kitty.

Actually, I don’t get the picture. I’m not even sure if you mean a financial debt.

That’s typically how the white right responds “I just don’t understand”. Which is why everyone will continue to pay for the sins of the past until they are compensated.

No, I literally don’t understand what you want when you say “compensate for the sins of the past”. Does this mean money? Is this a specific reference to people ODOT bought land from for its projects?

Partly.

Thanks for the clarification!

Then what else? Specifically, what sort of compensation do you feel is appropriate?

Yes — I was reflecting back what I hear from you so often.

Ignore.

The money kind. We reward people for all kinds of things. It’s not hard to do the math.

Now we’re getting somewhere. What are the factors we would use to make the calculation?

The Federal government paid out reparations to the Japanese Americans incarcerated during WWII. Seeing as how black slave labor built this country, Federal reparations to descendants of slaves ought to be on the table.

I am sure this is funny for you. But it isn’t for those who were displaced.

I’m not joking with you. It’s just hard to understand what you are asking for if you won’t tell me even the basic things you would think about when determining how much someone should be paid.

“There’s a convoy coming. It’s full of [people of a different race]. We can’t allow their kind in. They are dangerous to our culture, and will change our community. They speak different, they dress different, they have a different culture, their skin is a different color. We need to keep them out. Our community should not ever have to change because people would like to immigrate into it. We should instead prevent those other people from moving here.”

This sounds oddly familiar.

–

On the one hand, yes this neighborhood’s creation is a horrible history, and yes there’s a contemporary affordable housing shortage. On the other hand, do we really want to enforce racial housing rules so that people of color can only live in one neighborhood, or enforce rules so that only people of certain races can live in certain neighborhoods?

–

And, to me, even more salient: are black people less deserving of safety improvements in their neighborhoods than white people in theirs? Is it really *more* racially fair to deny safety improvements in black neighborhoods, for fear of making the neighborhood safer, and thus whiter? That’s a catch-22. The city either makes the neighborhood a pit of disfunction to keep wealthier (mostly, but not all, white) people out, or it gradually makes the neighborhood safer, as it does with every other neighborhood.

–

If a bikeway on 7th is a better option in terms of safety for the very people who live in this neighborhood, I think the solution is public art and more listening sessions and more touchy feely and, in the end, a bikeway on 7th. If we, as a culture, value black people’s bodies as much as we value white people’s bodies, we owe this neighborhood no less.

“If a bikeway on 7th is a better option in terms of safety for the very people who live in this neighborhood, I think the solution is public art and more listening …”

Are *you* listening?

It seems to me that the folks who live there are using different metrics, view these choices differently than you.

I totally agree, and I hope you continue to feel that different points of view and different ways of seeing things should be respected in the future.

My respect for different points of view is filtered through the mal-distribution of power.

Cars-first, screw-cyclists perspectives, when voiced by ODOT get no respect from me.

What passes for this from NE Portland’s longtime and mistreated residents I hear very differently. Both because of the speakers and because I’m not sure it is championing cars over bikes as much as it stems from a different set of priorities I readily admit I haven’t had a chance to understand yet, and I’d like to.

I don’t think ODOT qualifies as a legitimate voice of the people; you won’t hear me saying we should treat them as such.

I’ve been listening since the Williams debacle, almost a decade ago, and I think it’s fine if the City wants to keep listening, and fine if historic education ends up as part of a really effective, really safe bikeway. What am I supposed to think, though, when someone’s “different metrics” has a negative effect on my own personal safety, and, especially gallingly, the very poorest people of color in their own neighborhood? My metric for our streets is safety first. Why should I concede any other metric as a first priority? NE 7th currently does not have diverters; has that successfully prevented the neighborhood from changing? Is there any proof that maintaining unsafe cycling conditions on this street will prevent gentrification??? I’m listening, alright, and I have yet to hear an answer to these questions.

–

There are huge, powerful reasons black people are hurting. Safety improvements on city streets ain’t one. But, cyclists are a useful scapegoat for people (black or white!) who don’t want to lose car access. It reminds me of the environmentalists who get more angry, passionate, and active in their fight against mountain bikes than they are passionate about real resource extraction or global warming. Since it is practically impossible to fight the wealthy, national industrial machine, it can feel like a sort of reclaiming-of-power to prevent mtb access to a local park, for example. “Those loggers/miners/gas drillers are too powerful for me to stop, but at least those mountain bikers are disorganized and don’t have a billion dollar lobby in DC, so I can keep them out of my forest!” The ruling class have it made: instead ganging up on the power, we minorities (whether transportational or racial) fight each other for scraps.

–

I advocate for the bike lane way out on Holgate. Some residents didn’t want it because cars.

I advocate for diverters on SE Lincoln. Some residents don’t want them because cars.

I advocate for the diverters on SE Clinton. Some residents didn’t want them because cars.

I advocate for the road diet on SE Foster. Some residents don’t want them because cars.

I advocate for the diverters on NE 7th. Some resident don’t want them because. . . wait, you expect me to believe that the objections from this neighborhood are truly rooted in something completely different from all the other human neighborhoods in our town, or even, our country?

–

This one neighborhood? This neighborhood alone gets an excuse to advocate against my safety? All around Portland neighborhoods are changing fast, and damn near every person I talk to about it is pissed about it. No one likes change, whether in NE or SE, whether black or white. No one wants bike lanes. No one wants diverters. No one want apartment buildings or density. No one want the immigrants. Replace “Go back to California” with “Go back to Mexico” and see how that feels. The residents who watched black people moving into old Albina neighborhood generations ago probably yelled “Go back to Mississippi” (or worse) when black people, hoping for a better life, moved to Portland. This neighborhood is no different. We are a flawed species, groping toward the light. This neighborhood is no different.

–

Preventing safe bike facilities in this neighborhood won’t bring back Albina, but it will prolong unsafe traveling conditions for the hundreds of people who use that street, or who have to navigate N Williams instead. I see no justice in that situation, and no metric of justice would recognize dangerous streets as a benefit.

I don’t totally agree with your point of view, but I do appreciate that you have a clear-eyed set of principles that you can apply across the board.

Thanks for taking the time to explain all that. Maybe you’re right. I hope we get to find out.

You asked:

“My metric for our streets is safety first. Why should I concede any other metric as a first priority”

I guess for me it boils down to this. You feel passionately that your metric is not only right, but trumps anyone else’s. Because you know, deep down, that everyone who doesn’t share your safety priority just wants continued unfettered car access which you are unwilling to grant them, or resents gentrification. If you are 100% correct, fine, I agree, that is lame, and doesn’t measure up well to what we both seem to think this world and our neighborhoods need. But what if you are not right? What if, like so many others, your deeply held belief that your view is the superior one is flawed, partial, inadequate, but one among many equally valid perspectives? What if those who oppose your ‘safety’ actually don’t just resent gentrification, but actually have something else in mind, something constructive, something plausible? Why can’t they be allowed to fade fine their own view, ranking, stance?