for the State of Washington, spoke at this

morning’s opening plenary.

(Photos: J. Maus/BikePortland)

The “shared vision” of transportation reform advocates was literally on display at the kickoff of the Oregon Active Transportation Summit this morning. The event, organized by the Bicycle Transportation Alliance, is being held at the Sentinel hotel in downtown Portland today and tomorrow.

I’m covering the action for the first part of the day, then our News Editor Michael Anderson will take over in the afternoon.

The summit started with an opening speech by Lynn Peterson, the former transportation policy advisor to former Oregon Governor John Kitzhaber who was recently forced out of her position as director of Washington’s Department of Transportation.

Peterson shared lessons learned from the successful passage of the Connection Washington Transportation Investment iniviative that will pump $16 billion into infrastructure over the next 16 years. That plan includes mandates to “design to the minimum, not the maximum standards.” Peterson said the engineering profession abides by too many standards based on always building the largest project possible instead of “least-cost planning” standards. Peterson encouraged attendees to always challenge assumptions. As an example she pointed out how up until a few years ago Washington set advisory speed limits on curves based on standards created by a Model-T Ford.

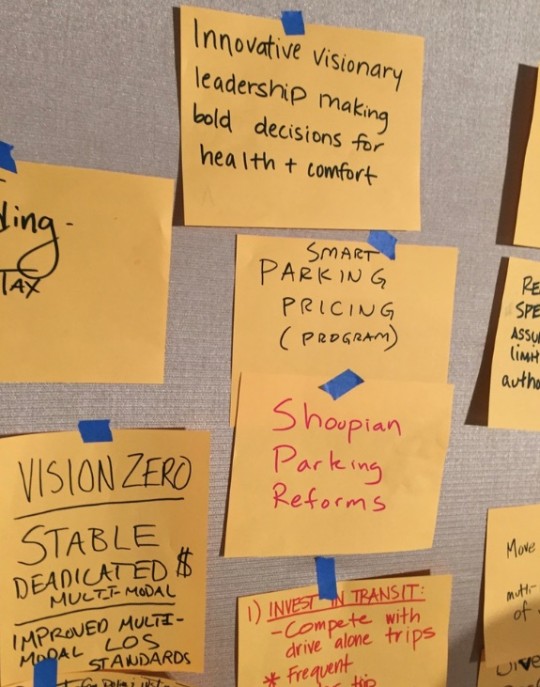

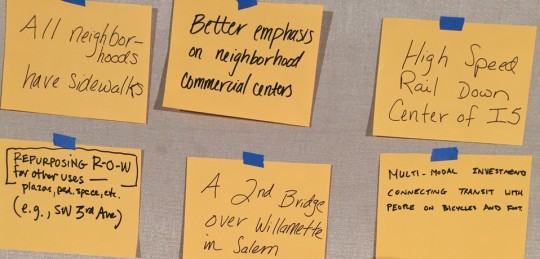

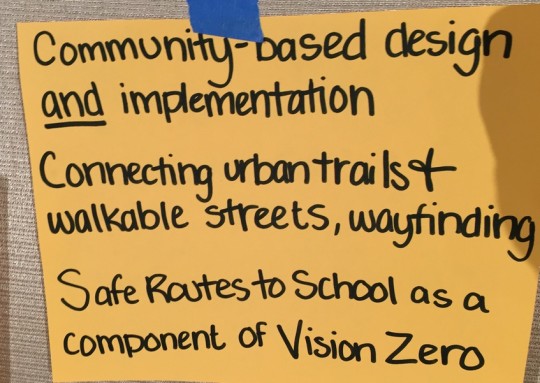

After Peterson’s speech, BTA Directors Stephanie Noll and Rob Sadowsky had the crowd work together to write down and prioritize programs, policies, and projects that should be our state’s “share vision for healthy streets.” They then posted the responses on stage and read them allowed. Sadowsky asked the crowd to keep them in mind during this election season. “Wouldn’t it be great to have an elected leader who believed in these things,” he said. And Noll asked the crowd, “What is your role in getting us here and what do you need from others in the room to get here… Let’s keep having those conversations today,” she said. It was a good way to kick off a full day of inspiring panel discussions and workshops. Below are a few photos of the responses:

Advertisement

The Myth of the Freight-Dependent Economy

My first session of the day was a presentation by economist Joe Cortright. You might know Cortright from his work with City Observatory and articles he writes for various outlets. His goal today was to slay the myth of the “freight-dependent economy.” Transportation agencies love to talk about the importance of freight and it’s commonly used as justification for expense freeway and road widening projects. But is it really necessary?

“If private companies aren’t willing to spend their own money to make goods move faster, that’s a pretty good sign that you don’t want to spend public money on it.”

— Joe Cortright, economist

Cortright says no. In fact he says the myth is perpetuated by “the cargo cult” and that’s based in thinking from 100 years ago. With a black-and-white photo of a horse and buggy on the screen, Cortright said, “This is the image policymakers carry around in their heads to this day… It says, ‘If you don’t have the railroad come into your town, your town is screwed.'”

Cortright’s fundamental point is that successful economies are based in the creation of ideas and new products — not in how much stuff they move around their roads. During a recent trip to Italy Cortright found craft beer brewed in Portland in a tiny town in the country. “That had nothing to do with freight and everything to do with the quality of the product we make here. Transportation costs are essentially irrelevant.”

Put another way, he shared a slide titled “Backwards Logic”:

“We export things because we’re good at making them.

We don’t make things because we’re good at exporting them.”

In true Cortright fashion, he backed up his words with lots of data. Despite the constant refrain from some transportation policymakers that freight viability is an urgent crisis and that it’s always growing (and thus needing higher capacity roadways), the overall trend in Oregon is that volume of freight miles driven and the value of what they haul is way down. Meanwhile, the economy is on the upswing and we’ve got record lows in unemployment.

“Incremental improvements to our freight system will do nothing to transform our economy.”

— Joe Cortright

Specificaly, the type of products that are on the rise in our region are from high-value industries that ship relatively tiny amounts of freight. And heavy goods like gravel and logs are not dependent on fast delivery and are usually staying local. “We’re creating as much value as ever while moving 42 percent few tons of physical goods,” Cortright pointed out.

The value of shipped goods in past decade in Oregon is up 55 percent, while the tonnage is down 44 percent. That’s a stat Cortright says, “Has everything do to with creating valuable ideas.” On a broader level, a metric known as “freight intensity of GDP (gross domestic product),” that measures the proportion of GDP that relies on freight, is trended way down. Each unit of GDP produced in Oregon is done with 20-25 percent less freight than a decade

ago.

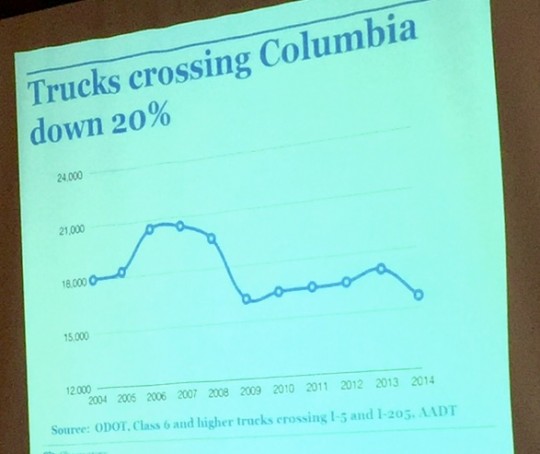

A central tenet of freight proponents is that truck traffic is up and will continue to go up into the future. It’s almost a basic assumption in some planning circles. But facts prove otherwise. In Oregon, truck traffic is at its lowest level since 2000. And for a very local and relevant political example, the number of trucks crossing the Columbia River (where many people wanted to spend $4 billion in the name of freight), are down 20 percent in the past eight years.

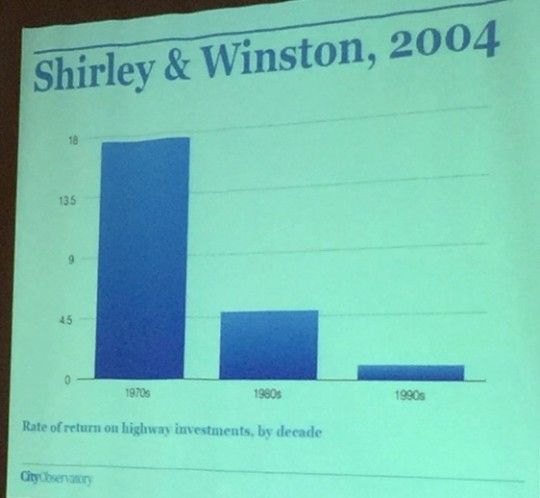

It’s important to understand that Cortright isn’t anti-freight. He doesn’t want to abolish our existing network, he wants to optimize it without adding to it. He warns about diminishing returns of road investments. “Once you have a [road] system in place, increments to that system have much fewer benefits… Incremental improvements to our freight system will do nothing to transform our economy,” he said.

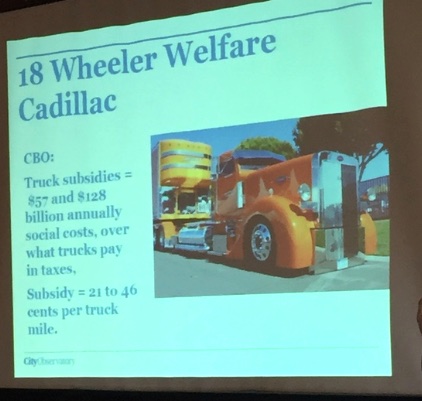

Not only is freight not essential to our economy, Cortright says, it’s also expensive and heavily subsidized. A study from the Congressional Budget Office estimated that trucks are subsidized by taxpayers to the tune of 21 to 46 cents per mile driven. In fact, Cortright says, “Trucks are often a value-subtracting activity because of high costs.”

In the end, Cortright says it comes down to making smart use of public funds. “If private companies aren’t willing to spend their own money to make goods move faster, that’s a pretty good sign that you don’t want to spend public money on it.”

You can view Cortright’s entire presentation here.

How are Local Governments in Oregon Pursuing Vision Zero?

This panel, moderated by founder and director of the Vision Zero Network Leah Shahum, came just days after the national Vision Zero Summit was held in New York City. Shahum’s at the center of a fast-growing network of cities across the country that are actively working on Vision Zero initiatives.

“We’re going from taking over the streets to going after the systems and policies that need to change.”

— Leah Shahum, Vision Zero Network

In just a few short years, the concept has caught fire, changing from an enigmatic phrase uttered by activists to a mainstream program taking root at every level of government. “We’re going from taking over the streets to going after the systems and policies that need to change,” Shahum said.

The panel included staff from the cities of Portland and Eugene as well as Clackamas and Linn counties.

The Portland Bureau of Transportation’s Margi Bradway was frank in her description of why Vision Zero is a huge priority at her agency. “We have, very clearly, a pedestrian problem in Portland. They make 9 percent of trips, but 31 percent of deaths,” she said. “We are a leader of a lot of things, but we are not a leader on traffic safety.”

Bradway used the phrase “traffic violence” and pointed out that it consistently causes more deaths in Portland than homicides. “It is one, if not the killer in Portland.”

One of many actions PBOT is taking is to wrest control of speed limits away from the State of Oregon. Currently the Oregon Department of Transportation controls speed on all streets in the state — even ones they don’t have jurisdiction over. If PBOT wants to reduce a speed limit, they must put in a formal request at the State Speed Board. In response to an audience question, Bradway said that process is “Hugely frustrating and arcane… We wait from six months to a year-and-a-half.” PBOT has reached out to ODOT to reform that process, but it’s “going slow” Bradway said.

Stay tuned for more stories from the Active Transportation Summit. Next up I’ll have some pictures and updates from some of the advocates and city staffers I’ve run into this morning.

— Jonathan Maus, (503) 706-8804 – jonathan@bikeportland.org

BikePortland can’t survive without subscribers. It’s just $10 per month and you can sign up in a few minutes.

Thanks for reading.

BikePortland has served this community with independent community journalism since 2005. We rely on subscriptions from readers like you to survive. Your financial support is vital in keeping this valuable resource alive and well.

Please subscribe today to strengthen and expand our work.

Cortright: “Transportation costs are essentially irrelevant.”

I see where he’s going with this, but I’d have hoped he could have also noted that the single reason for this, and for much of the rest of what he said is a century + of cheap fossil fuels. With the looming end of that, his premise and argument will change. I’m sure he knows that, but it wasn’t clear from the presentation.

I only harp on this because I think it is important at these sorts of shindigs to be very clear about how much will change in our lifetimes. From that presentation you’d never have guessed it.

Appreciate the interesting piece on freight, but I find it difficult to comprehend the idea that freight is not important to the economy. Most of the physical goods in our lives–even caffeine–has to come a long way to us via freight. If the freight tonnage in this region is down significantly, is there some other reason such as major shipping lines abandoning our ports?

You’re correct, of course. But you have to remember the Cortright is an economist. Economists always pay attention to what is expensive. Fossil fuels have not been expensive. Although everything pretty much that arrives at our doorsteps got there with large helpings of fossil fuels, because, relatively speaking, those inputs weren’t a large fraction of the cost (so understood), economists feel comfortable not paying much attention to them (even smart ones like Cortright, apparently).

If the economy is doing ok, does that mean we don’t have to care much about road congestion that causes businesses to have difficulty delivering their products to customers? What comfort to businesses struggling with congestion to move freight to points along I-5 south of the river, is the study data suggesting that twenty percent less freight in recent years has been crossing the I-5 CRC?

The mention of Model T’s used to speed limits on curves, attributed to Linn Petersen was interesting:

“…Peterson encouraged attendees to always challenge assumptions. As an example she pointed out how up until a few years ago Washington set advisory speed limits on curves based on standards created by a Model-T Ford.

T’s top speed is slow compared to modern cars, and their ability to stay upright on turns is far less than modern cars. It was an economy car too. Safe speeds on curves for such cars would be slower than for cars with more sophisticated engineering, and that were bigger and faster and more expensive…like Dusenberg’s, Packards, Buicks and so on.

I don’t think it’s about freight being an unimportant aspect of the economy. As you say, it’s a fundamental part of it. I think the point is that *promoting* freight isn’t going to improve the economy. Take the example you gave–coffee. We’re going to buy coffee and it’s going to be shipped, whether we build a new freeway lane or not. Adding that new lane is not going to alter the amount of coffee we import or export–the small expense that could be avoided by reducing traffic isn’t going to increase coffee imports or exports (obviously hypothetically, since adding that freeway lane would likely have no long term affect on traffic).

Much of freight is the materials and products that communities need to sustain themselves: food, clothing, building materials and so on. Road congestion slowing the transport of freight, can cause the cost of these things to people that need them, to rise. Locally grown and produced can help some to reduce congestion, but there’s generally some transport involved for these things as well.

Cortright has a point in saying that smaller, less weighty, higher value products mean fewer trucks to transport them, which could partially explain the percent reduction in freight across the river over the years. As a strategy for countering congestion, hoping to sustain that kind of correlation doesn’t seem like a viable plan.

Biggest issue seems to be population increase, which is something nobody appears to be claiming will decrease. Everyone seems to think it’s going to increase. Such increases generally result in greater demand to meet people’s travel needs from area roadways.

Freight in Portland has impacts on the local (Portland), metro-wide, regional (OR-WA), and super-regional (10 state area). Until local policy wonks start really looking at the local level impacts of super-regional and regional freight needs and demands, nobody will really address the underlying problems of freight for transportation in Portland. People tend to get bogged down in thinking that if they go to the store and buy some coffee, they are participating in the freight economy, which is true, but in Portland, the Freight economy has a great transportation HUB. The HUB is the rail nexus of the super-regional area. This rail hub is serviced by many local truck trips in the Portland area for freight which neither originates in Portland nor is destined for Portland. Nobody seems to want to discuss this in a policy sense. This freight lobby need to maintain super-regional shipping container businesses and is controlling PBOT and ODOT policy on freight for places like SE 26th Ave, SE McLoughlin Blvd, SE 7th Ave, NE Interstate, NE Going, NE Greeley, and the Central Eastside – all feeders and local truck-driven shuttles inside the rail network. To them, the residents of these areas are just an impediment to smooth flow of international cargo. Sure, some of these containers are hauling Christmas trees from Estacada going to Taiwan, or straw bails of animal feed from Stayton going to China, but many of them are hauling Wal-Mart goods from China headed to Chicago. Of course, we need to maintain smooth delivery of goods headed to and from local (Portland) businesses and consumers, but people need to realize that the Freight policy in Portland is set by the needs of far off business and consumers, whether they are farmers down the valley, Chinese factories, Rail barons, or consumers in Ohio. This transport hub that runs through the heart of inner East Portland contributes greatly to our road congestion, poor air quality, and has a nominal benefit to our local economy. Freight lobby hides behind the needs of local business (say a produce distributor in central Eastside) to set local freight policy at the city and state level which really benefits these far off interests at the detraction to local residents. Sure, there are needs for interstate truck traffic to flow up and down the west coast, but I am talking about all of the heavy truck traffic flowing on Portland city streets hauling cargo neither headed to or coming from Portland, just stopping off for a transfer on a long trip or coming from other regional areas to hop on the rails, here.

As resident of Eugene, I found Rob Inerfeld’s participation interesting. He’s the traffic planner for a city that has had 50% of its roadway deaths represented by cyclists and pedestrians over the past decade (and he’s been here longer than that). He should know something about how a city can be the opposite of a good example of vision zero, but that’s about it.

Sadly, this CARnage has occurred over a time frame that has seen massive losses of cyclists. Eugene lost 37% of its cycling commuters back to cars over the past five years. Perhaps these former cyclists are assessing the relative risks and coming to the conclusion that the odds just aren’t good enough.

What are the Portland Police doing to stop this killing?

Stop sign enforcement in Ladd’s Addition.

Will they also be exploring the myth of the necessity of free storage of personal motor vehicles in the public right-of-way? How many bike and pedestrian projects that would improve safety for vulnerable users have been shelved or severely compromised to protect the parking status quo?

So the OREGON Active Transportation Summit was held in Portland. I guess it should have been called the Portland Active Transportation Summit.

This should have been held in our State Capitol. And it should have been held during the recent legislative session. But I guess when everything revolves around Portland (at least to Portlanders, including all the state employees and advocacy groups), then of course you’d locate a summit that’s about he whole state in Portland.