After 38 years, the end of the line has come for Citybikes. At least for now. The shop will close this Friday (September 13th) while the remaining owners decide what to do next.

Rumors have swirled about the organization’s demise for years and BikePortland confirmed its fate today with one of its last remaining owners. After a reader shared a sign that recently popped up on the front door of the shop on Southeast Ankeny Street, I emailed Bob Kamzelski (who also owns Bantam Bicycle Works) to find out what was going on.

“Citybikes will be ceasing retail and repair operations on the 13th of this month,” Kamzelski wrote. “After 15 years of declining sales, and taking more than $120k in losses over the last three years, it has become obvious that the business is not sustainable and we have made the decision to stop operating while we figure out what to do next.”

The shop and worker-owned cooperative was an institution during Portland’s heyday as a cycling mecca. There were once two locations on Ankeny (at SE 20th and SE 8th), but the “Annex” on 8th closed in 2016 amid a decline in business. At its peak, Citybikes had 25 worker-owners. Last I heard there were just four (three in addition to Kamzelski).

A messy lawsuit between current and past co-owners that came to light in 2022 was likely one of the final attempts to change the direction of Citybikes.

A former worker-owner, Brian Lacy (who, coincidentally, founded the Community Cycling Center), was spearheading an attempt regain control of the organization from Kamzelski and others. At the time Lacy told BikePortland, “We’re going to rebuild Citybikes. We don’t want it to die.” But reached today via email about the pending closure, Lacy said he knows nothing about it.

And while Kamzelski said he plans to close the doors while they figure out what to do next, his comments to BikePortland in 2022 don’t make it sound like the shop will ever reopen.

“It’s not a viable business anymore,” Kamzelski told us two years ago. “It’s been a very successful run and I’ve been here for a third of it. I just think it’s time to move on. Other shops are closing. It’s a very hard time to run a bike shop.”

Thanks for reading.

BikePortland has served this community with independent community journalism since 2005. We rely on subscriptions from readers like you to survive. Your financial support is vital in keeping this valuable resource alive and well.

Please subscribe today to strengthen and expand our work.

Bummer

What a shame. Back in the mid-80s, I worked just a few blocks away from them. I biked in most days, so they were my regular bike shop for a few years.

Two blows to City bike shop infrastructure today. Real bummer. I feel partially responsible for buying parts at REI, Amazon, and eBay from time to time. It’s even more of a kick in the pants knowing that REI, too, had pulled up steaks and withdrawn from the City. We get what we pay for…

REI left because we normalized & excused away crime against commercial storefronts, not because you bought a couple parts on eBay.

City Bikes, both Ankeny storefronts led the way. Those two shops will return in another name for the same services. Bicycles are forever. Electric scooters suck.

OK boomer.

Guilty. I’ve got this idea for a self-driving scooter: it recognizes when it’s on a sidewalk and won’t go faster than a walking speed. Scooters, bicycling, walking too will never be safe until the car-dependency problem gets somehow fixed.

You believe that propaganda. They left because of declining sales, not the imaginary rise of retail crime.

REI left because the space they were in was too small for the business they were doing and shoplifting was a convenient political scapegoat at the time. Oh and because the workers were organizing a union.

After reading these comments, REI left because of shoplifting, declining sales, too many sales for their space, and potential unionization. Others have said it was because their lease was up and the landlord didn’t want to make certain improvements, that the city wouldn’t provide security, or that Portland’s business taxes drove them out.

Glad we’ve got that figured out.

What we do know for sure is that they left, that to shop at REI now requires a trip to the suburbs (by car for most of us), and that for outdoorsy types, this is a big loss.

It’s a shame that Portland is no longer able to welcome a store like REI in the urban core. Luckily we still have some decent alternatives.

There’s always Next Adventure. Better options for used gear anyways, and in a cool old historical building to boot

Indeed. They’re first on my list of “decent alternatives”.

Actually, in recent years, REI occupied top spot on my list of “decent alternatives to Next Adventure”.

Frek too, went from Downtown anchor to trendy blight NW rebirth with tiny little presence, I could hardly find the place and I doubt they want anything to do with any of the ground level misplaced cyclists I saw in the empty courtyards.

This news makes me sad.

Definitely a blow. Was the first shop I ever went to in Portland. Hope everyone involved with the shop lately is doing alright, it was a really lovely space

Nostalgia doesn’t sustain business. This is just more evidence of the death of the old Portland. It will finally just live in our collective minds.

All things must end. It was a good run.

RIP Citybikes! They were always kind and patient with me anytime I went there. Sorry to see them go.

Your experience there was far different than mine. Noel and a couple other workers whose names escape me at the moment were cool but there were a few who were so rude, dismissive and impatient that I haven’t been to City Bikes in many, many years. This, to me, is sad in a RIP Old Portland kinda way, but that’s all.

The drama here is amusing, so I’m thankful for that.

You just came up with the name for the new bike shop that should take their place.

Neighborhood bike shops are an indicator-species of a healthy urban environment.

This does not bode well.

Who woulda thought…another socialist “worker-owner” co-op goes under. I visited Community Cycling Center on Alberta with the same type of business model and it was a total joke. No surprise both are finished.

They actually have very different business models.

The Community Cycling Center is a non-profit organization

CityBikes is a for-profit worker-owned cooperative.

Regardless of the future of either organizations, most businesses of their scale, regardless of business models last >30 years.

LOL! You probably don’t even ride a bike. How is a co-op “socialist”? REI did the exact same thing, as well as University Cycles in the same hood. This is about the bike shop industry and brink and mortar retail; not socialism.

REI is a customer owned co-op, which is fundamentally different than a worker owned collective like CityBikes. Customer owned co-ops run much more like a conventional business, overseen by a board elected by owners. They’ll typically have a conventional management structure.

There are few odd-birds out there like Alberta Co-op and People’s who are both consumer owned and collectively managed, where the employees manage themselves according to policies set by the board, but do not have a direct ownership stake (unless they are also members, which not all are).

None of these arrangements is “socialist”, and probably couldn’t even exist in a true socialist economy.

Citybikes started in 1990. Pretty damn good run by socialists. Go socialism

Weird how when dictatorship style companies go under every day it’s not an indicator that that type of business model is a joke.

Can you explain in better detail how a worker cooperative is a bad business model?

Yeah, 30 years of being a successful business only to see sales decline unsustainably since the pandemic until now, yeah what looser’s.

Interesting what this articles doesn’t mention is that CityBikes sold a building for likely $1million this last year. This is my opinion: The 3 current worker owners who locked the 4th worker owner out of the business. (Literally changed the locks.) Want to close the business. Liquidate and keep the profits for themselves. My best understanding by observing the behavior of the current worker owners is they don’t want the business to look sustainable because they want to cash out.

The current court cases are about the legality around shoving the other owner out for not wanting to close and liquidate. And my impression is there is another case about whether every worker owner who has invested time over the lifetime of the bike shop should be paid out of the closing surplus.

I don’t know how the current three worker owners justify closing a community business and potentially earning so much profit for themselves. It seems unethical.

Note: CityBikes owns the house it works out if and recently owned and sold a building in inner SE. It’s supposed to be a cooperative not an early retirement cash cow for 3 people who appear to have mismanaged the business.

Thanks for sharing! Reporting so weird. Can be so one sided.

Thanks Jolyn. I am not always able to find out all the angles and insights into every story. I appreciate you sharing this information and I will consider taking a closer look at this for a future story.

Thanks Jonathan! It’s true about all those angles. How would you know. I have a different perspective because of my proximity to their community. And have worked with different staff members over the years as City Repair, People’s Food Coop, and City Bikes used to support each other with meeting facilitation and mediation.

Please do !

FYI – I wrote to bikePortland about the issues Joyln is bringing up (I am a former Citybikes co-owner) when the previous article came out about owner issues and nothing came of it/wasn’t contacted.

As someone who went there regularly for 20 years, after the last article you wrote about them I mentioned that the current owners should pass the torch to someone willing to continue. A week later I went in with my kid and the “owner” literally asked if it was me (out of the 100s of comments) and said I was not welcome in the shop ever again. He literally told me to leave. I haven’t gone back and instead started going to other bike shops. I can’t be the only one that had this happened to them

Is it a “community business”? The way you describe sounds like an employee-owned business. Those can be structured a lot of ways, but it’s the employee-owners who make the decisions and set the goals and priorities, not the community.

Yes, but it’s a worker owned cooperative with by laws. And some of those bylaws speak to community. It also has an extensive list of worker owners who have contributed to the business over the years. I don’t have a problem with them deciding to close and sell. I have a problem with how they are doing it. Because I think they aren’t following their cooperative bylaws. And there was 4 employee owners. One of them didn’t want necessarily close or sell and wanted to bring it to the larger community of worker owners. And the other three locked a worker owner out of the business. A person who has worked there for decades. Because he wasn’t agreeing with them. That seems concerning and uncooperative. Also not community minded.

Did the bylaws specify how decisions were made? Did major decisions need to be agreed to unanimously, or by majority vote?

From their Wikipedia page: Citybikes operates with consensus-based decision making. The majority of decisions that affect the cooperative are made in bimonthly general meetings, with all workers present having equal say and voting power. Day-to-day operations are also carried out by consensus – Citybikes does not have any managers or traditional hierarchy. The board of directors is made up of the worker-owners, and is responsible for the long-term interests of the cooperative, setting goals and making final decisions on policies and procedures.

I see. So they don’t have consensus to sell off their assets, but the majority current owners can (in essence) go on strike / run the business into the ground so they have no choice. That does sound tricky. It’s kind of the nature of democracy, actual power lies with what a majority decides (even if formally they run on consensus), and they can decide to do bad things. Unless what they’re doing actually is illegal in some way, which I hope it is. I’m sure whatever profits they end up making by selling off assets (if that happens) will at least have to be shared with the current owners.

I suppose if you lock the dissenting owner out, it’s easier to reach consensus.

I don’t know all the details, or if anything you said was true, but if the coop sold a building and wants to cash out, what on Earth is unethical about that? I’m sure they’ll have to do something about the one owner who doesn’t want to sell, and if they don’t that would be unethical (I’m sure illegal). But what are you leaving out that would make selling a building and going out of business unethical?

It’s not unethical to sell the business. It’s unethical to lock one of the owners out and sell it against that persons will and not pay that person out. It may be unethical to sell a worker owned business that had 50 other previous owners with years of investment and not pay them out, too. It’s in court so a judge or jury will decide.

The current worker owners will walk away potentially with $400,000(this is a complete guess given lawyers fees etc.) Because they claim the business wasn’t manageable /financially viable. They didn’t buy these buildings or invest in all the infrastructure of the years of business. They are cashing out on something that was built as a cooperative and they are doing it in an uncooperative way. I personally think it’s unethical. And as I said earlier it’s my opinion.

Cooperatives even worker owned ones aren’t regular companies.

That said, if the Citybikes owners (or a subset of them) wanted to increase the amount “they’ll walk away with”, they could offset some of their capital gains taxes by “buying out” CCC, essentially becoming the CCC’s largest creditor, and more gradually “realize” their return on investment from selling the Citybikes building(s). CCC has good prospects for long-term income from PCEF-funded grants, so all the Citybike owners would need to do is reorganize the CCC board (eliminate everyone) and gut the management (fire employees), accumulate funds to allow the cash surplus needed to do the PCEF grants, then hire gig workers (1099 MISC) as needed to do the projects. While individuals at CCC would be screwed, the community gains from the continued existence of CCC and the core mission would continue.

And if that’s what’s truly happening, I hope they face legal consequences. If the bylaws of CityBikes really says that all former owners have a stake in some way, and that they need full consensus to make this decision, then they’re in violation of the bylaws.

I’m not advocating for what these owners should be doing. But from other comments I’ve read it sounds like maybe the bylaws weren’t so clear in what say the former owners have. Certainly people are sad about what’s happening. I am, and I’m not a former owner. All I’m saying is if the bylaws don’t say they can’t close up shop and take the money, I don’t see anything unethical about doing it, in the same way a sole proprietor could decide to retire and sell the business. But it’s a legal dispute to be resolved. Writing good bylaws is one of the trickier parts of running a co-op, as I understand it.

I miss the days when you could rummage through the back room at CityBikes and find who knows what random thing. I don’t know anyone else who stocks all sorts of odd random used bits that, when you need them, you need them.

Yep. Citybikes was a unique shop in my experience. One that built a sense of possibility and empowerment that I didn’t feel at more traditional bike shops.

Bike Farm! Washco bikes in Hillsboro.

CityBikes is where I bought my first commuter bike after moving to Portland, a bike I still own to this day even though I have more bikes now and rarely ride that first one. But it’s my old standby, just a nice, solid, affordable commuter bike. Thank you, CityBikes, for all your years of helping people find their bikes!

As a former member of 24 years, i can say that this is an unnecessary move. All former owners (50) are in agreement that the co-op is still viable and see this closure as just a asset grab on part of Bob and one other present owner. I have letters from Bob’s lawyer stating that they feel they are entitled to all of Citybikes assets (two buildings one of which just sold for a million dollars, which certainly could have floated a restructuring of the business.) Attorney letter will be forthcoming

The former owners have had over two years to buy the business and save it. I haven’t seen any one of you put your money where your mouth is.

Running a collective in a capitalist landscape has always been a bit of tilting at windmills.

It’s an idea that simply doesn’t attract enough altruistic people, especially in a 2024 economy.

Part of the blame lies with the founders who, when they wrote the bylaws, never anticipated the potential greed of future generations; and so no provision for dispersing assets to all previous owners was ever created.

Part of the blame lies with the three remaining owners, who saw that omission as their chance to clean up and did so.

I worked at Citybikes for nearly two decades. Other than my skill set and a little profit-sharing I will have nothing else materially to show for it — and I *knew* that would be the case when I left. I never earned enough there to save anything for the future, had no meaningful health coverage, and understood even then that in some ways, it was a cooperative more in name than in practice. In a capitalist economy, it couldn’t really be any other way.

I’m not sorry to see it close.

It’s past time to move on.

Let the three remaining owners worry about their own karma, and I will tend to mine.

A collective is a very pure form of capitalism, with the people who work there are also being the owners (no different than a partnership). The owners decide how to allocate the capital, not the state (socialism) or “the people” (communism).

The problems collectives face is that it can be cumbersome to make decisions with so many cooks in the kitchen. That’s a human problem, not an economic one.

Potato potahto. I (and other socialists) see worker owned cooperatives as a step in the directon of Socialism. They are far more democratic (i.e. socialist) than any other workplace which literally has dictators by another name.

But if you want to call them pure capitalism, go for it! I just want to see more of them. I don’t think the too many cooks in the kitchen issue is really a problem in reality. It’s not like regular corporations don’t have legal scandals and badly written contracts and mismanagement and other kinds of failure. There’s just a lot more of them so we see some that stick around a long time.

I see them as the highest form of capitalism, so we both agree that, decision making aside, they are great when they work!

I will admit I’m confused why a socialist enterprise (where the state owned the enterprise) would be more democratic than a capitalist one where the workers themselves owned it. Care to expand on that?

My comments about too many cooks was about the difficulty making decisions when there are 30 people who have to agree (less of a problem in a 4 person collective), which is a different problem than poorly written contracts and the such. It’s not necessarily a comment on the situation at CityBikes, which had a different set of issues.

Sky High has a good answer to these questions. But to say it another way – socialism is not when the government does stuff, or even when it owns stuff. That’s one way to do it, because if the government is truly democratic, the government owning stuff is the same as the workers owning stuff.

A worker owned co-op is a literally worker owned means of production. It’s a small commune bubble, if you will, existing in a capitalist context. The people doing the work decide what to do with the profits democratically. You’re right that it is no different than a partnership, until the partnership starts hiring employees.

A regular corporation is an undemocratic dictatorship. Sure people are free to leave, just like people could migrate away from a king they didn’t like before enclosure and modern strict border enforcement. But the operation of the business is a top-down authoritarian organization.

To answer your particular example, with a state-run enterprise (that’s != socialism), if the state is democratic then the workers have democratic control over their workplace. So does everyone else, and that can run into problems, but it doesn’t have to be organized that way. A “capitalist one where the workers themselves owned it” is sort of a contradiction. They’re running their business in a capitalist run government, but themselves are very much not operating like capitalists. Same as any actually existing communism in history that had to operate in the context of a capitalist dominated world.

However you define things, it is an undisputable fact that co-ops and collectives are part of capitalist systems all around the world, and are entirely compatible with our laws and frameworks. Oregon (along with most states) has a specific set of laws that support co-ops/collectives, so they clearly aren’t just a quirky corner case that a cigar chomping capitalist failed to eradicate.

If you consider collectives socialist, then that part of socialism is a subset of capitalism. That’s fine with me — I see capitalism as the “big tent” of economic systems.

Your statement “but themselves are very much not operating like capitalists” falls prey to the No True Scotsman fallacy. Collectives operate exactly like capitalists, with the owners deciding what to do with the proceeds of their enterprise.

That’s trivially true. It’s an indisputable fact that the USSR was part of a capitalist system all around the world. But internally, they were anything but.

A co-op is operated in a fundamentally different way from any other business. It is literally the core difference between socialism/communism and capitalism. In a worker-owned co-op, the workers are in control, in a regular corporation, they have no power except to leave (sort of). This is the main definitional difference between capitalism and socialism. You can say “then there is no such thing as socialism” because you don’t know what the word means, but that’s what it is.

It’s not a no true Scotsman fallacy. When things aren’t the same, they’re not the same. You’re just saying it’s that fallacy because you don’t agree, but that’s your opinion. The key is that worker-owned co-ops are run by the workers. That’s a fundamentally different thing from a regular owner-employee corporation.

It’s not a fundamental difference; you could have a conventional corporation that makes decisions with a consensus mechanism, or a collective with an owner-appointed board that chooses a manager who makes decisions on behalf of the organization.

It’s true that collectives (different than co-ops like REI, which operate much more like “capitalist” companies) and conventional corporations tend to choose different mechanisms, but that’s more due to logistics and size than anything.

Either type of organization could choose either operating model. Alberta and People’s co-ops are good examples: the workers have no ownership stake, but make all the decisions. It’s cumbersome in practice, and they are pushing the limit of how big they can get with that management system. And Mondragon (Spain) is a worker-owned collective with a conventional management structure; it’s far, far too big to make decisions collectively.

Not really. A conventional corporation could “let” their employees have a say, but the final say is with the owners. In a worker owned co-op (what you’re calling a collective), the final say is with the workers. They can decide to elect a leader, but they can un-decide that too. And all this depends on the bylaws, but it ultimately starts with a democratic process, unlike a traditional corporation.

And co-ops like those grocery co-ops are misleading, because they are not worker owned. If the workers have no ownership stake, they don’t really make all the decisions. If they did, they could decide to make themselves owners.

Mondragon is worker owned and operated exactly in the same way a democracy is operated by the voters. They have a say.

I mean, I guess like in a democratic government, the participants can vote themselves out of their own democracy. They can change their bylaws to have an authoritarian leader, no takebacksies. Sure. At that point, it wouldn’t really be a worker owned collective anymore by any reasonable understanding.

In my view, a worker-owned collective is basically a small socialist enterprise. A good thing. If you want to say they’re perfect capitalism, again, go for it.

Yes, ultimate control lies with the owners, in both cases. The thing that defines a collective work is that the owners happen to also be the employees. That’s a consequence of who owns the company, not some fundamentally different economic system.

Any company could become a collective if the employees wrote up a contract amongst themselves and bought it out.

I used Alberta and People’s as examples of how non-employee owned companies could be run by employees. Ultimately, yes, the collective management needs to follow the policies set out by the owners (though since employees have a seat on the board, and decisions are made by consensus, employees have a significant voice in those policies), but how they do it is up to them. There is no general manager or other owner representative with any voice at all in day-to-day operations. And at Mondragon, the workers do indeed have a say; the same say that a shareholder of any company has over its board. It has a very conventional corporate structure.

You are arguing that when the workers happen to own the company it becomes radically different, transforming from a capitalist system to a socialist one. But you have pointed to nothing that fundamentally changes during that transformation. This is because nothing does fundamentally change, and I am sure you are not arguing that socialism is just some happy quirk of capitalism.

Collectives are just one flavor of capitalist enterprise.

(Here’s a slightly but not too contrived example of how your analysis doesn’t work, based on a scenario you mentioned earlier. Three partners own an equal share of their company: socialist. They hire a secretary: suddenly capitalist. They lay the secretary off: back to socialist. They sign a contract with another company to provide secretarial services: still socialist, even though the new secretary has fewer legal rights than the earlier one. Is the difference between capitalism and socialism really so trite?)

Yes! It is radically different! That’s the whole fundamental difference between capitalism and socialism! What doesn’t make sense to you?

Who owns it is the transformation! This is so simple!

This is like “you’ve pointed to indentured servitude compared to capitalism, but nothing fundamentally changes besides who is allowed freedom to choose where they work”. It’s a giant difference.

Your example makes no sense, because yes of course something can fluctuate between varying levels of “socialist-like”. It’s not like there is some sharp, fine line. Signing a contract with a company to provide services, which may not be collectively owned, is indeed an unfortunate consequence of living under capitalism. The same way I consider myself a socialist, but cannot actually survive without participating in capitalism. The difference between socialism and capitalism is who owns the rights to labor, and in a collective, that is the workers (like in socialism).

A socialist government is one big collective enterprise. If you have many of them, that is just a bunch of collectives. If you have a capitalist economy, but every company happens to be a worker owned collective, that is not fundamentally different than many socialist governments.

The key you refuse to acknowledge is that who owns the business is the key difference between capitalism and socialism. That’s like the whole thing. All sorts of details and philosophies stem from that, but the root is that ownership of means of production belongs with the workers. That’s a collective.

I will accept your definition if you will accept the consequence that “socialist” enterprises are welcome first class players in a capitalist economy, and, aside from that overlap between ownership and employment, are not fundamentally different from other enterprises.

I accept that they are welcome (in ours at least!), and I would also suggest that any economic system puts its thumb on the scale to favor whatever kinds of business it wants. Capitalism favors private ownership and wage labor. So under our system, co-ops tend to be harder to put together and may be less ruthlessly able to compete, because we allow alternatives that are willing to exploit labor more harshly. So we “allow” collectives but they can only be the most competitive if they exploit their workers (themselves). Just like we “allow” drivers to drive carefully, but it’s too easy to do otherwise.

I mean yes, if you want to simplify it, the difference between capitalism and socialism is nothing aside from that overlap between ownership and employment. Facts. But “nothing aside from that overlap” is doing a lot of heavy lifting there though.

Maybe a succinct way to express this is that socialism is a forced overlap, whereas capitalism is the freedom to overlap if you so choose.

“A worker owned co-op is a literally worker owned means of production. It’s a small commune bubble, if you will, existing in a capitalist context. The people doing the work decide what to do with the profits democratically.”

AND…

As in any human-run endeavor, those with the strongest/most assertive personalities have the most social capital to sway decisions closer to their liking, often at the expense of members with quieter or less confrontational personalities. So the “democratic” aspect was, and could not be, truly democratic.

AND…

Citybikes was never a commune, or a community. It was a business.

Owner-members were paid an hourly wage. Hours were tallied each year so that profits could be distributed based on how many hours one worked in a given year. The resulting period payouts amounted to a few hundred dollars per check for most owner-members, over a period of multiple years (depending on how long one remained an owner).

There was no meaningful health coverage, because before the ACA — and with multiple owners seeking coverage for chronic or preexisting conditions — the costs of entering into such a plan with an insurance company were prohibitive. The best that could be done was to set up an annual Health stipend paid out to each owner based on the hours worked in the previous year. (Full disclosure: my Health stipend never amounted to more than about $1,200 a year. For someone with multiple chronic conditions, that was chump change, especially in the years I earned too much to qualify for the Oregon Health Plan.)

In short, in order for the system to function, everyone had to agree to a standard of living that made it difficult or impossible to buy a home, start a family or save for retirement — unless you lived like a monk or were married to someone who earned more than you did. Considering how rapidly the cost of living rose in Portland over the last twenty years, that system stood on an increasingly shaky foundation, and it was no surprise to me every time an owner chose to leave — for college, a better paying job, or whatever else.

Living like a monk is fine when you’re young — and I think everyone should try it, at least for a little while. But as we age, our needs change; and working in a bike shop was never going to be a lifelong pursuit for most folks. Anyone joining the cooperative was quickly disabused of the notion of a long term career early on, or should have been.

Change is Everything.

Well, yes and no. Nothing is going to make human relationships go away, you always have to deal with that. It’s the human condition. But being democratic is not a binary, and worker owned co-ops are more democratic.

Citybikes was a collectively owned business. Yes, this is akin to a commune. You don’t have to be afraid of the word, it describes the situation. It’s not a dirty word.

The rest of your comment amounts to the unfortunate reality that it doesn’t make that much money to run a bike shop. Collective ownership doesn’t generate money out of thin air, it only lets you decide as a group what to do with the money that is earned and how you run the workplace. If someone wants to work on bikes for a living, even temporarily, that sounds way better than getting paid less somewhere else so the shop owner might be able to buy a house.

“Citybikes was a collectively owned business. Yes, this is akin to a commune. You don’t have to be afraid of the word, it describes the situation. It’s not a dirty word.”

A commune is generally understood to include shared living arrangements, whether within a cluster of houses surrounding a common area, or a very large share living space. A commune could be considered a kind of family of choice, depending on many layers of context and purpose.

Citybikes was most definitely NOT a commune. It was a for-profit business, whose stated mission was to provide meaningful employment for as many people as possible, in a non-hierarchical, consensus-driven structure.

At the end of the day, workers went home to their very separate homes and families. Annual all-cooperative “retreats” included meetings about matters of the business that needed attention.

We did not celebrate holidays together as a collective.

We did not celebrate regular communal rituals for strengthening and sustaining a sense of community unless they were a direct outgrowth of the work we did in the business.

While I did enjoy some friendships among the staff, I did not consider any of these people to be part of my family structure in intention or in practice.

This was not a commune, but a collectively-run business.

And that is probably why I have so few deep emotions around my history at Citybikes today. It was not a marriage, but a job. And I am okay with that. I wish the other former owners well and hope they find some closure.

Yes, it’s an analogy. It is analogous to a a commune. It doesn’t include the living arrangements, but rather the shared goals and common interests. I was trying to avoid outright saying it’s a little socialist organization to avoid the red scare triggers, I guess the point didn’t get across.

Whenever I hear an organization claim to be “non-hierarchical”, I understand that to mean they’ve swapped a transparent formally defined hierarchy for an opaque unwritten one based on personality and popularity.

Some people thrive better in one than the other, but I absolutely know which I prefer.

Worker owned business is not socialist by any definition unless you think REI is a socialist enterprise. This is a laughable discussion.

REI isn’t worker owned, I thought someone already corrected you but maybe it was someone else. There are lots of things people call co-ops, only worker-owned ones resemble socialism, in the sense that the workers own the company and run it in some collective process. CityBikes was this kind.

REI is a consumer co-op, which is a cursed naming convention that confuses a lot of people.

No worker owned companies in the US are socialist by any definition.

Everyone is operating in the Capitalist system.

They are all for profit companies.

You are so ignorant it is embarrassing.

I mean, by any definition other than most definitions of socialism.

The global economic system is capitalist. Does that mean socialism just doesn’t exist?

Call worker owned co-ops “collectives”, and consumer owned co-ops “co-ops”.

You can, but they’re all called co-ops, and I think it’s more informative to just distinguish them by what they are or aren’t (e.g. worker-owned co-op, consumer co-op).

I see no reference to a “collective” on this page, for example:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Worker_cooperative

Agreed. And it’s hard to check your self-interest at the door in a collective endeavor. Which I suppose is why I didn’t expect anything magical or even greater than the sum of its parts while I worked there. I made my peace long ago and hope others can do so as well.

If things are structured right, you shouldn’t have to — things work best when your self-interest is aligned with that of the enterprise, which is why, in principle at least, collectives should work better than a company where the owner hires people who may not have the best interest of the enterprise at heart. As you noted, if the charter had a requirement that previous owners would get a share of the assets in the event of dissolution, that would diminish the incentive to take the money and run.

One possible advantage that a conventional company has over a collective is that it’s easier to get specialists… instead of 6 bike mechanics who also try to mange the business, you have 4 mechanics, an accountant/buyer, and a chief decision maker who does whatever else is needed. You could do that with a collective ownership structure, but that’s rarely how it works.

Socialism=/=the state

Socialism is when the workers own the means of production, and in some forms this can be through government control of industry, but certainly not all.

Anarchism is also a form of socialism. Under Anarchism no state would exist at all.

A collective is not a pure form of capitalism. That’s nonsensical. Capitalism is when the means of production is privately owned. Collectives are not that.

Collectives also have fantastic ways to make decisions. Many use forms of Formal Consensus, which, when people have an understanding of how the consensus process works, makes it not cumbersome at all. It only seems cumbersome because you are so used to only one person or a tiny group of people making decisions for everyone else.

Please do not try to over simplify these socio-economic systems so they can fit your narrative.

Don’t tell that to an anarchist!

That really depends on your definition of “capitalism”. If you view capitalism as something like “market based competition”, then I see what you are getting at. But that’s not really how a socialist would frame capitalism – since the pertinent thing is the private control of capital in pursuit of profit in a market. Big capital tends to seek out the highest possible rate of return on their money, rather than seek to be the best solution for their original business. This is why US Steel bought out Marathon Oil in the 1980s rather than investing in modernizing their steel production – more profit to be made in oil.

If US Steel had been owned by the workers in the 1980s, it’s exceedingly unlikely that they would have spent a bunch of money buying an oil company because the workers have a vested interest in spending capital to improve their own working conditions. Worker owned industries also don’t send their factories overseas, though even the presence of a strong labor union tends to be enough to prevent this (part of why US industrialists have been more successful than their European counterparts in moving production overseas).

Still, the motivation to seek out the highest rate of personal profit does play a role in cooperatives and evidently played some role in why City Bikes is closing (from what I can surmise anyways). There’s always a risk in any business that ownership will prioritize short term profits over long term stability. I’m of the opinion that cooperative structures tend to be more stable in some ways (good collective ownership naturally prefers to reinvest in itself) while being less stable in others (more prone to being pushed out of the market by other firms which do ruthlessly pursue the highest profits, and thus have more expendable capital).

For me, I think of things as being socialist if they are founded in ideas that workers should have the power over their workplace. And in this sense, a collective is socialist – or it at least has a lot in common with socialism

To me the most important aspects of capitalism are the private ownership of capital, and the freedom to contract (not necessarily in an unregulated manner — I’m absolutely not an absolutist).

Competition is a consequence of what I wrote above (but you can also have competition in a socialist economy), as is the opportunity to pursue profit.

Some workers may prioritize working conditions over making more money, but given that most people work specifically to get money, I’d expect most workers to choose whichever course of action makes the most money for them, just a individual owner or group of shareholders would.

And, behold, that’s exactly what’s happening at collectively owned CityBikes.

You simply can’t have a collective without private ownership of capital and contracts. With those tools, you can create whatever sort of enterprise you want, be it a collective, a co-op, a sole proprietorship, a B-corporation, or what have you.

You’re looking at co-ops as an entity within capitalism. They are, factually, a thing that can exist in a capitalist system. But that’s a useless definition. You can’t just use the definition of “anything that happens in a capitalist-run country is capitalism”. It’s facile.

What we’re (at least I’m) saying is that the internal operation of a co-op is socialist. There is no private ownership of capital within a co-op. Because everything is – get this – cooperatively owned. Everyone owns it. That’s definitionally not private ownership. And as for contracts, a co-op has its founding documents (whatever they’re called), a sort of contract, but that has to be agreed to by everyone in the co-op. I.e. the workers. In a regular corporation, a small group of share holders owns the capital and dictates the terms of the contracts, and all the rest, usually the vast majority, owns nothing and has no say in the contract terms.

Of course everyone in a co-op is working for their own self interest. That’s how it works under any economic system. In a worker-owned co-op, hopefully, self interest is aligned with the co-op’s interest. In the case of CityBikes, I don’t know what standing all the former employee-owners have. If their rules don’t say that former employees have a right to the sale of the business, there is nothing weird about what is going on. That’s up to the courts to decide. But the key is, the employee-owners decide to sell, not a small board of directors or whatever, which definitely won’t share the profits.

Why not? How is that different from any other privately held company whose bylaws restrict the ownership of shares?

My claim isn’t “anything that happens in a capitalist-run country is capitalism”; my claim is that capitalist systems support the creation of collectives (as opposed to co-ops, which are typically consumer owned) as first class entities on par with other types of corporations.

In a collective, all the owners get a voice in what happens, using whatever mechanism is written into the bylaws. In a conventional corporation, all the owners get a voice in what happens, using whatever mechanism is written into the bylaws.

I’m not sure I see the difference.

Seriously? The differences is in who “all the owners” is. You said it right there, are you pretending not to understand?

Seriously. Who happens to own the company is more of a happy alignment than some fundamental difference. Nothing changes when the employees acquire the last share of ownership.

What can change the flavor of the company is new bylaws, but I’ve given you examples where you can have a collective work environment without ownership, and others where you have a conventional work environment with employee ownership.

In other words, bylaws are independent of ownership. Changing the corporate bylaws is easier when you own a controlling majority of the company (51%, not the 100% needed to be “socialist”), but I’ve shown it’s possible to give employees complete control over their workspace without any ownership at all.

I am genuinely curious: after you’ve reviewed our conversation here and above, do you think you’ve made a convincing case (not to me — you haven’t — but to an open minded outside reader) that employee ownership is not just another flavor of capitalist enterprise?

At this point you’re just playing dumb.

An authoritarian government with a dictator at the head can have bylaws. The difference is in who gets to change the bylaws.

I’ve given you examples of where the bylaws and operating structure are independent of employee ownership. It’s not a reasonable response to just ignore those and call me dumb.

I didn’t call you dumb. On the contrary, I acknowledged that you understand my argument but you’re pretending not to.

You did not show me examples where bylaws and operating structure are independent of employee ownership. In all your examples, these things are all dependent on who owns the business.

This always the case. This does not change if the owners happen to be the employees or not. There is no fundamental change. Owners can make whichever polices they want (within the bounds of the law). That’s how both conventional companies and collectives work. They’re just variations on the same theme.

I do understand your argument (something fundamental changes when ownership happens to coincide with employment), but you haven’t made much of a case that there’s any fundamental difference.

You don’t get a change of working conditions when that happens — that requires changes to the corporate bylaws, which can happen with or without employee ownership (as I’ve shown with clear, specific examples). And changing corporate bylaws don’t teleport a company into “socialism” — it’s just a different set of boring old capitalist contracts.

If you don’t have anything new to bring to this conversation, I don’t think there’s any point in going further. I’ve made my arguments to the best of my ability, and I haven’t convinced you. We both like the collective business model (when it works), and maybe the economic philosophy is just too much for this forum.

Sorry for the double comment, I missed this.

I think to an open minded reader, at least some, I have made a case that there is a fundamental difference between working for a boss (a capitalist – an owner of a company) that makes all the rules and can decide by fiat who they hire and fire and how you work, and a collectively owned business where everyone who works there has a say in who they hire, fire and what all the working conditions are like.

There is a fundamental difference between working for someone else and working for yourself / a group that includes you. A collective is where everyone who works there has ownership.

What determines who has hiring/firing power is the corporate bylaws, not the ownership. You can have a company that gives employees control over employment decisions without ownership. This is exactly what Alberta Coop and People’s have done. An employee owned company does not need to have these policies, e.g. WinCo, where employees own a controlling majority of the company.

These are specific, local counter examples that contradict your assertion that this structure relies on employee ownership. It does not. Anyone who owns a company is free to institute these corporate policies.

I think you are conflating corporate policies letting employees self-manage with who owns the company, and letting your identity as a “socialist” cloud your analysis.

FWIW, BP has a nice, clean ownership structure, and very clear management too! 😉

But it’s capitalist.

Cold, hard capitalism.

I’m not confusing anything, and you haven’t provided counter examples to anything except whatever argument you have in your head.

Employee ownership is the only structure that guarantees the right of employees to at least have a say in how the company is managed. Any company can give some authority (however they want – bylaws, or otherwise) to an employee to do things whatever they want. But a worker owned collective is definitionally built on that power. The bylaws necessarily are written by the founding members and can only be changed by whatever process was laid out in those bylaws. That doesn’t mean they can’t democracy their way into an authoritarian structure or rid themselves of some of their rights. We do that in America all the time.

Regardless, you don’t have to think the worker owned collective structure is socialist in nature. Most Americans are too red scare pilled to use that word with a positive connotation. If you want to think of it as “capitalist” somehow, I can’t stop you. But it’s clearly a structure that gives more power and rights to the people who work there, which I think we should have more of. And I think most workers wish they had more of.

Excellent… we seem to have arrived at something of an agreement. We agree that the bylaws/charter/policies of a corporation (essentially a set of contracts) are what can empower workers (or not). We agree that when employees own a controlling share of the company stock, they have a greater power to alter the corporate documents to their liking, just as a majority of owners can in any company. (Stretch goal: We might even agree that when employees are fully aligned with the corporate mission the company should in principle operate more efficiently.)

You can call that socialism if you like, and see it as a fundamentally different economic model. I don’t see any real difference there — it all seems like standard capitalist corporate mechanics to me — but I’m happy to disagree on that.

Shared victory?

This is a mainstream capitalist belief though, not an intrinsic fact of life. There’s a reason that the abolition of the wage (and wage slavery) play a central role in historical socialist thought, if not so much in any of the existing structures in the US that have their roots in early socialist ideology (labor unions primarily). It’s because to some extent, reducing everything to profits and money alienates people from the other non-monetary benefits of labor – namely, working at things because you get satisfaction out of creation, or because you enjoy the literal process of doing so.

I think it’s also worth saying that competition is only a consequence of private ownership of capital insofar as no firm reaches a dominant or strongly leading position within the market. Tons of industries are more accurately understood through monopolistic pricing than competitive pricing. And that these factors are all ultimately also related to social ideas of what is acceptable. Maybe that’s a bit of a tangent though as it pertains to City Bikes, monopolistic pricing certainly isn’t something we worry about as it pertains to the local bike market (though perhaps there is still some tacit minimum price setting done by shops who understand that if they continually undercut each other on price, then they risk being ultimately taken over by larger firms).

I still think that the workers have a fundamentally different outlook on their prospects than shareholders would, I think they have obviously different interests. Workers care about long term stability of their workplace more than shareholders (especially more than shareholders who have a hugely diversified portfolio). Workers also care more about investments to improve their own working conditions. And yes, City Bikes is succumbing to the pressure of a quick profit it seems, but not without significantly more dissent and legal action than would be expected for any other bike shop in the city.

This is a very narrow view of what is possible. Throughout world history, tons of things that resemble collectives have existed without the same emphasis on private ownership of capital and the same type of legal structures we have now. Collective ownership of land, especially in the context of agriculture, was the norm for the vast majority of human history and still exists in many parts of the world.

I was focusing my comments on economic entities in the modern world. The reason CityBikes is tied up in legal action is because, in the opinion of some of the stakeholders, the contracts governing the situation have been abused. Many conventionally held companies also end up in a complex legal process when they unravel.

Though it wasn’t really the topic, collective ownership of pastoral land doesn’t seem completely dissimilar to government ownership of land, like the Forest Service or whatever. Ultimately there needs to be a dispute resolution process, and the decider is effectively the owner, even if there is no formal deed. If that process is collective, it basically boils down to a government in some form or another, even if it goes by a different name.

That’s my take after 5 minutes of thought, anyway.

I am a former co-owner at Citybikes. I was on the hiring committee that hired Bob, and the other two owners Bryce, and Claire, were hired and trained (I was one of their core trainers) through the Citybikes apprenticeship program. The fourth owner Noel, is the one who was locked out of the building and is now working at another shop, but has been a co-owner at Citybikes for over twice as long as the other three and wished to keep the business going.

They have allowed, and encouraged the business to run into the ground. In the history of the company through financial ups and downs no other owners have failed to realize it was time for them leave and let new people lead. And no other owners have sought to violate the articles of incorporation which states since founding that shareholders B, all former owners would receive a portion of any profits left after loan repayments should the company close and the two owned buildings be sold (with shareholders A, current owners receiving a significantly larger percentage).

The annex building is worth a significant amount of money, with its sale, a loss over the years of $120k is nothing and the sale of the annex could help the mother shop (so called by Citybikes staff) could weather the bike industry ups and downs.

I am genuinely heartbroken that the current owners have become so misguided in their quest to close the company. In other hands, it could be the go to community shop. Yes, other bike shops have closed, but in this situation these three have lost perspective and are taking the ship down with them.

Former owners spent months and months trying to help them see reason but two current owners in particular have been hellbent on closing. The third had opportunities to side with the fourth owner (who was locked out of the business) and all former owners to save the business but chose silent acquiescence.

It is a sad end.

Hi, Ash! Do you know what bike shop Noel is working at? I’m a long-time CityBikes customer (I live in the neighborhood) & Noel has has worked on my bike for the past many yhears. It’s time for a tune-up and I’d love to continue having him do that bc I trust hiim 100% (he does great work & I’ve always really appreciated that he didn’t try & sell me services that I didn’t need). Thanks!

Noel is now owns Wizard Cycles at 421 NE 12th Ave. Best mechanic in town!

Dang … Another shop bites the dust from the internet and high end bicycles.

First cat6, then Gladys now Citybikes and the Community Cycling Center is also very challenged with having enough business to stay open.

I don’t like to buy on line. I get the cost savings and immediate gratification for parts not in stock but we are putting are friends and neighbors out of business buy not buying local.

Online ordering also increases the impact of neighborhood traffic and the faster deterioration of our roads with more traffic.

Just a few of my thoughts on keeping our bike purchases local even of we have to wait. Our LBS’s are as important as our bicycle infrastructure. They are all connected.

ride safe y’all

John

City Bikes is everyone’s. Time for a new City Bikes

I worked at the Bicycle Repair Collective (which opened in 1976 in the same space) for five years prior to starting Citybikes in 1986, when they moved to 45th & Belmont (now home to Mount Tabor Bakery). One of the first things I learned there, was that the interests of the collective and the community superseded personal interests.

I didn’t enjoy being a sole proprietor and missed the collective management of the BRC, so at the end of our fourth season, inspired by a film about the Mondragon workers’ cooperatives in the Basque region of Spain, I donated the business to the workers and went to work for my friend Sherman Coventry.

Citybikes thrived under the stewardship of the wonderful people who took over. I was delighted and honored when they invited me to join them four years later. I loved working there. Needless to say, I was sad about its demise, largely due to the fact that its assets (the two properties, that I was involved in purchasing to make the co-op financially secure) exceeded the value of the business.

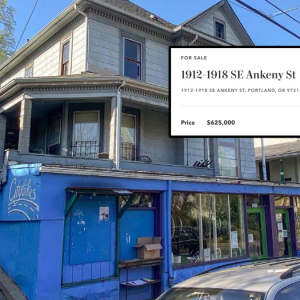

I learned today that the building housing what we affectionately referred to as the Mother Shop is on the market:

https://www.loopnet.com/Listing/1912-1918-SE-Ankeny-St-Portland-OR/35484134/

It is ideally located on Portland’s original “neighborhood greenway”, with a 48 year history as a continuously running community bike shop (in various guises). Some of my former co-workers & I fantasize about taking it back, but we don’t have the resources to do so. I would be delighted if it were to be home to a community bike shop again and hope that someone or a group were to acquire the property and make that a reality.