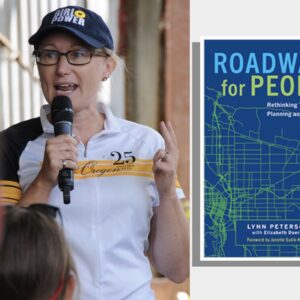

It took me a while to figure out who was the intended audience for Metro President (and now candidate for U.S. Congress) Lynn Peterson’s recent book, Roadways for People: Rethinking Transportation Planning and Engineering (co-authored by Elizabeth Doerr).

The short answer is, “probably not you.” The book is the collected wisdom of an accomplished mid-career professional, and would make a wonderful text for a graduate-level course titled Engineering 240: Transportation and Community Engagement. And if you are already a transportation geek who is seeking a deeper understanding of why Portland’s transportation system is the way it is, it’s a good guide into the belly of the beast.

For me however, I found it a bit disappointing — not because of what I read, but because of what I didn’t.

Before being elected the Metro President, Peterson was the secretary of the Washington State Department of Transportation for Governor Jay Inslee; the transportation policy advisor to Governor John Kitzhaber; TriMet’s strategic planning manager; and transportation advocate for 1000 Friends of Oregon — as well as being elected to the Lake Oswego City Council, and chair of the Clackamas County Commission.

Drawing from that deep background, Peterson illustrates many of her points with examples from Portland. The book builds to a middle chapter titled, Addressing the Racist Legacy of Transportation and Housing Policy in which she uses the destruction of the historically Black Lower Albina neighborhood, and the controversial I-5 Rose Quarter Freeway widening and capping project, to illustrate ineffective community engagement, and she criticizes the Oregon Department of Transportation (ODOT) for it.

Early in the chapter she recounts the destruction of Albina between the late 1950s into the 1970s as I-5 was routed through the heart of the neighborhood. In the name of urban renewal, Portland allowed houses and businesses in this neighborhood to be razed to make way for the Memorial Coliseum, the Rose Quarter, Emanuel Hospital, Lloyd Center, and the Portland Public Schools Administrative Building.

From that sad and disturbing history, which is well-trod ground, Peterson pivots to present-day racial equity initiatives, the Rose Quarter widening and capping project, and she recommends Ibram X. Kendi’s 2019 book, How to be an Antiracist, as a starting point for one’s own antiracist journey. The chapter ends with instructions for how to bring a racial equity framework to the reader’s transportation work.

It is in the construction of a narrative that views all actions through a racial lens that I become aware of the accumulating errors of omission. For example, in Peterson’s discussion of “deep-listening” to the community, “community” always seems to mean Albina Vision Trust, the nonprofit that seeks to redevelop Albina and that Peterson hitched her position on the project to. But when invoking “community,” Peterson never mentions No More Freeways, the protesting students at Harriet Tubman Middle School, the Eliot Neighborhood, the Sunrise Movement. None of them make the book. She excises global warming from the discussion.

There might be pedagogical reasons for that, a clean simple narrative could be the easiest way to introduce the evolution of different programs for community engagement, but it strips the current Rose Quarter freeway expansion controversy of its flavor. It sanitizes a complicated story and makes it bland.

Similarly, in a section about overlooked and undervalued ethnic neighborhoods, Peterson turns to neighborhood greenways (PBOT’s bike-friendly residential streets) as an example of how “Whiter, wealthier neighborhoods were becoming safer as a result of these improvements…” But that overlooks the fact that the whitest area of town, southwest Portland, has the fewest number of greenways. That fact is not useful for her narrative.

My final example is the destruction of the Albina neighborhood itself. What Portland did is horrible, and the city is a less vibrant and humane place because of it. But Albina wasn’t the only neighborhood in Portland destroyed by urban renewal and freeway building. The Portland Development Commission also razed 54 “blighted” blocks in South Portland, home to a working class Jewish and Italian neighborhood. That ethnic neighborhood was so annihilated that there is no longer evidence that it ever existed. Between the South Auditorium Urban Renewal project, (the area around Keller Fountain), Interstate 405, the surface streets of Highway 26 and the Ross Island Bridge ramps, “block after block of south Portland homes, businesses, bars, churches and rooming houses [were cleared] … And by the mid-1970s, new construction had taken the place of most of the old structures.”

Again, leaving out the context of Albina’s destruction serves to support Peterson’s narrative.

My examples are not a three-part exercise in whataboutism. I’ve written all over this part of my book with marginalia — a lot of it question marks and exclamation points. To be transparent, I’ve given money to No More Freeways which opposes the Rose Quarter expansion of I-5. Peterson approves of the Rose Quarter Project, as she makes very clear.

However, I have a flexible mind, I can be convinced. But this section lost me, it skipped too many steps in the chain of logic, and left out the inconvenient facts that could make a too-clean narrative messy, and that just might make a story interesting.

By the end of the chapter, I found myself not completely trusting my narrator, and wondering if Peterson might be part of a cohort of traffic engineers who badly want their legacy to be having rectified the mistakes of a previous generation.

I do not think I would recommend this book to many people. You have to be pretty deep in the policy weeds to appreciate it. But for those who do jump in, it offers an illuminating peek into the ideas that appear to animate the higher levels of Portland’s transportation culture.

Thanks for reading.

BikePortland has served this community with independent community journalism since 2005. We rely on subscriptions from readers like you to survive. Your financial support is vital in keeping this valuable resource alive and well.

Please subscribe today to strengthen and expand our work.

Thanks for the book rec!

Something I find eternally frustrating about the Rose Quarter project is how it is really two entirely different projects (a freeway expansion and a freeway cap) lumped into one. It “had” to be this way because the freeway expansion on its own was dead in the water in Portland, and ODOT does need the city to cooperate. Adding the cap was a way to garner political support for the expansion, and it needs to be viewed in this light. Because if ODOT were truly serious about restorative justice for Albina, they would be pushing ahead with a freeway cap even if it meant a different approach for the expansion/congestion fix that they were directed to do by the legislature. Since they aren’t doing this, I can only assume that they view freeway operations as more important than restorative justice for Albina.

Anyways, there are a myriad of stories to tell about urban renewal, freeway building, and the mid 20th century in Portland. They are all interesting in their own ways, but I would have been far more interested if Lynn Peterson chose to talk about I-205, and how Lake Oswego and Laurelhurst essentially forced the state and cities hands respectively to move the alignment further south and east. Because ultimately the real issue at hand when it comes to freeway building and expanding is political power – Lake Oswego and Laurelhurst were able to wield enough power to move a freeway, while Maywood Park, Lents, and Albina were not.

What does “restorative justice” mean in the context of a place, rather than people?

Do we have any inherent obligation to places? There are lots of places we’ve utterly destroyed. Or does it make more sense to see it through the eyes of general urban improvement?

I personally think the caps are going to offer a small-to-modest benefit that comes with a disproportionately high cost.

I agree with you. My thoughts on the project are this; let ODOT build their just one more lane bro, but nix exit and surface street garbage. Give the city money to build a bunch of dank bike/ped bridges across the freeway and infrastructure to reach them.

“What does “restorative justice” mean in the context of a place, rather than people?”

This brings up an irony to me. Clearly N/NE Portland neighborhoods and the people who lived and worked in them were harmed when the freeway went in. Caps will help mitigate some of the damage done to the place.

But most of the people harmed have died or moved away (including of course those who moved when their homes were demolished), some by choice, some driven out as the area gentrified.

So almost all of the people who will benefit from the caps are the people who replaced those who were harmed by the freeway going in. The caps are portrayed/celebrated as a healing project, but are decades too late to benefit the people harmed. I could see some of those people feeling like the system was rigged against them.

This project ignores all the people who live along the 1-5 corridor between the rose quarter and the IBRP/Columbia Crossing. They are already living with exceptionally bad air quality, and the freeway widening to the north and south of these neighborhoods is guaranteed to create increased congestion on I-5 in their neighborhood and diversion through their neighborhood. Where is the justice for the existing neighborhoods? Any amount of freeway widening under the guise of restorative justice’ is bs because it comes at the expense of displacing freeway impacts onto an existing neighborhood. Portland should fight like hell to avoid adding a lane through the Rose Quarter and admit that the cap is a distraction.

Yes, I agree with all that, and that was also my point. The caps or other mitigations will help the place, not the people who were harmed when the freeway went in (because they’ve almost all died or moved).

Also, when I say the caps or other mitigations will help the place, I mean the widening with them is better than the widening without them, but I agree that it would be much better to skip the widening altogether.

My main point was that the people originally harmed by the freeway going in are not getting any benefit from the caps, and when the caps are referred to as “restorative justice”, that term implies–at least to me–that they’re somehow restoring justice to the people originally harmed, which isn’t true.

Additionally, the pollution emitted under the caps is going to go somewhere, most likely into the lungs of people living on either end of them. So the “restorative justice” for the place will actively harm current residents.

They can filter it.

That never happens, even in long tunnels.

These freeways harm residents (especially children) every day, all hours of the day. Don’t downplay that.

Yes, I agree. But those vast majority of those children aren’t the children or even grandchildren of the people who were originally harmed. Of course they should be protected (the best way being not to widen the freeway, but still to do mitigations to reduce the impacts the existing freeway already has).

But imagine parents whose grandparents had the freeway go in next to their home, then moved away because they didn’t want their children growing up next to a freeway. Now the children of those children read that caps are proposed as “restorative justice” decades after it’s too late to matter to their parents and grandparents who were the ones originally harmed. It’s not any kind of restorative justice for them.

Any “justice” happening is helping the place, but not the people originally harmed, so using terms like “restorative justice” is misleading and sugar-coating in my opinion.

The phrase is a critical fundraising tool for the non-profits profiting from the project. By greasing the skids for financial transfer, it plays an important role.

In general, our obligation is to people – places matter in how they relate to people and their lives. Lets consider the aborted Legacy Hospital expansion that demolished the blocks around Williams/Russel. Restorative justice could look like subdividing that land, building homes for displaced Black Portlanders and giving it to them – focusing on the families who were directly affected by said demolition.

It’s obviously a little more difficult for something like I5, where the chances of full scale removal are slim (unfortunately). But the general idea holds, and if the freeway cap gets built the best use of the very high cost cap from a “justice” stand point would be similar. Giving it to the people or families who were displaced or negatively affected.

From here, I think it’s fair to consider that maybe a $750 million dollar price tag for 4 acres of land is a little steep. And that capping the freeway with just greenspace might provide enough benefits for the surrounding area that the fringe lots and parking lots could be bought and given to families instead. Or when the time comes for Memorial Coliseum to be retired, that land could be redeveloped in the same restorative way.

My grandparents were forced to moved by highway construction (but not in Albina). I also once had to move because the owner of my building wanted to redeveloping the site. I’d like to get some property for that.

But don’t forget that the freeway caps will make it *LOOK* like something is being done to right past wrongs. In Portland, the optics are always the most important thing.

Being a bullsh*t artist is practically requirement #1 for elected officials these days. I do wonder if Janette Sadik-Khan read the book before writing the foreword, though, especially after Sadik-Khan’s brutal tweet about the Rose Qtr freeway expansion a few years ago…

Which tweet? Can you share it, please?

This is great review/critique. It sounds like President Petersen is decrying the ills of freeways while simultaneously using her considerable power to greenlight further expansion and continued destruction from them. I guess politics is the right place for type of person, but I find that pretty gross.

“a narrative that views all actions through a racial lens”

Indeed, could have been climate instead, something that devotees have said.

It’s the choice of one kind of current activism in place of transportation versus the other current and related one, Equity, or the much-older Climate activism, and will have fans, particularly those most devoted to race obsession and reverse racism. It includes activists in government who routinely substitute politics for governing.

Jonathan,

Are you her new campaign manager? Two articles in a week? She was fired as director of the Washington State Department of Transportation due to a “laundry list of concerns, including cost overruns, management failures and project delays” and hasn’t done any better at Metro.

I am sure your fine eye for comprehensive reading caught that in two separate spots, it names the author who penned this book review and neither time was it Jonathan 😉

Mr. Maus is included at the bottom of article because he’s the Big Cheese.

I made this comment on one of Lisa’s earlier articles but why do people like Lynn Peterson only talk about Albina?….the razing of the Jewish neighborhood in Portland seems to have been forgotten…the “renewal” of the Black community of Portland (Albina) although equally problematic was not the only community destroyed (by urban “renewal”).

Please do not forget the historically Jewish neighborhood of Portland was also destroyed by development during an urban “renewal” project in 1958. Yet all we hear about is Albina nowadays. It’s very odd that Portland is feeling more anti-Semitic even as it races to embrace “racial justice”.

“And then in the late ’50s and early ’60s, a series of highway projects and Portland’s first urban renewal program cut the neighborhood to shreds.The Portland Development Commission declared it a blighted neighborhood, ” Olsen says, and razed 54 blocks

https://www.oregonlive.com/portland/2011/12/tales_of_jewish_south_portland.html

https://www.hadassahmagazine.org/2009/10/23/jewish-traveler-portland-oregon/

Thank you Jim and thank you Lisa for reminding us of this painful yet important part of Portland history.

SW 3rd Avenue in the South Auditorium URA was the heart of a small Gypsy (what is the proper word?) community as well in the 50’s. And South Portland had Black residents as well. Who has done a thorough account of the SA URA?

PS the Auditorium was there since 1917!

Romani is the proper word

Thank you Lenny for catching my mistake about the auditorium. I’ve re-written that paragraph and included a link to more information. Refresh your browser and changes will appear.

Metro and Peterson have had an enormous pile of voters’ tax money for homeless shelters and affordable housing (about $700MM over the past couple years, I think). As of last year, Metro was already missing its targets.

https://www.portlandmercury.com/news/2022/08/31/46028887/metros-supportive-housing-bond-falls-short-on-first-year-goals

Peterson celebrated the “achievement”, said Metro was just 1 year into a 10 year effort, and got re-elected with some pretty lukewarm endorsements.

https://www.wweek.com/news/2022/04/27/wws-may-2022-endorsements-metro/

Now she wants to bail, just 2 years into her 10 year effort?

It seems to me there is enough track record on which to judge this candidate. Her book is irrelevant, to me.

In January of 2021 in her State of the Region speech, Peterson promised there would be visible progress in 6 months on the homeless front using the tax heavy “housing first” approach. (NEWSFLASH: It’s worse!). She was quick to blame the group People for Portland and their push for rapid sheltering of our unhoused. She’s been very quiet lately. I wonder why?

Peterson said progress is being made and promised that things will start to look different within six months, thanks in large part to the 10-year, $2.4 billion supportive services ballot measure approved by Metro voters in 2020.

Metro chief promises visible progress on homeless crisis soon (newsbreak.com)

But, hey, say “bikes” a lot, and this website will give you lots of free promotional articles and deliver lots of votes. It’s a pretty well-trodden campaign path by now.

Thanks so much, Lisa, for reading this book, so I don’t have to. (TBH, I probably wouldn’t have read it anyway.)

To be successful in Portland politics, you don’t need to learn how to govern – you need to learn how to perform governance.

To be successful in Portland communication, you don’t need to know how to communicate – you need to perform communication.

Peterson has been wildly successful in Portland-area politics, so she has perfected the art of performative governance and communication. I’m not surprised to hear that her book is packed with platitudes about how she’s righting the wrongs of previous generations. Facing up to the evils of people who are no longer here is a lot easier than facing up to the evils perpetrated today – the stuff we are doing and condoning, like widening freeways and speeding the death of the planet.

It’s kinda sad that Peterson is apparently the best our politics can produce.

WA state was a bit wiser. They fired her. Portland voters not so wise, they re-elected her after a subpar performance.

At a recent event when I heard Peterson say (multiple times and with gusto) how much she loves concrete, it became perfectly clear she gives not too shits about climate. After reiterating this a number of times she paused and, as an aside, acknowledge how bad concrete is for climate, I realized she wasn’t naive, rather, she was knowingly giving the middle finger to climate.