“Portland used to be a mecca for transportation innovation.”

– Nina Byrd, Friends of Frog Ferry

It was just last summer when supporters of the non-profit initiative Friends of Frog Ferry (FOFF) announced their pilot program for a ferry to whisk passengers up and down the Willamette River was set for imminent launch. But a lot can change in a year. On Tuesday officials behind the project announced the dream of a Willamette River ferry system is no longer alive in Portland – at least for the time being.

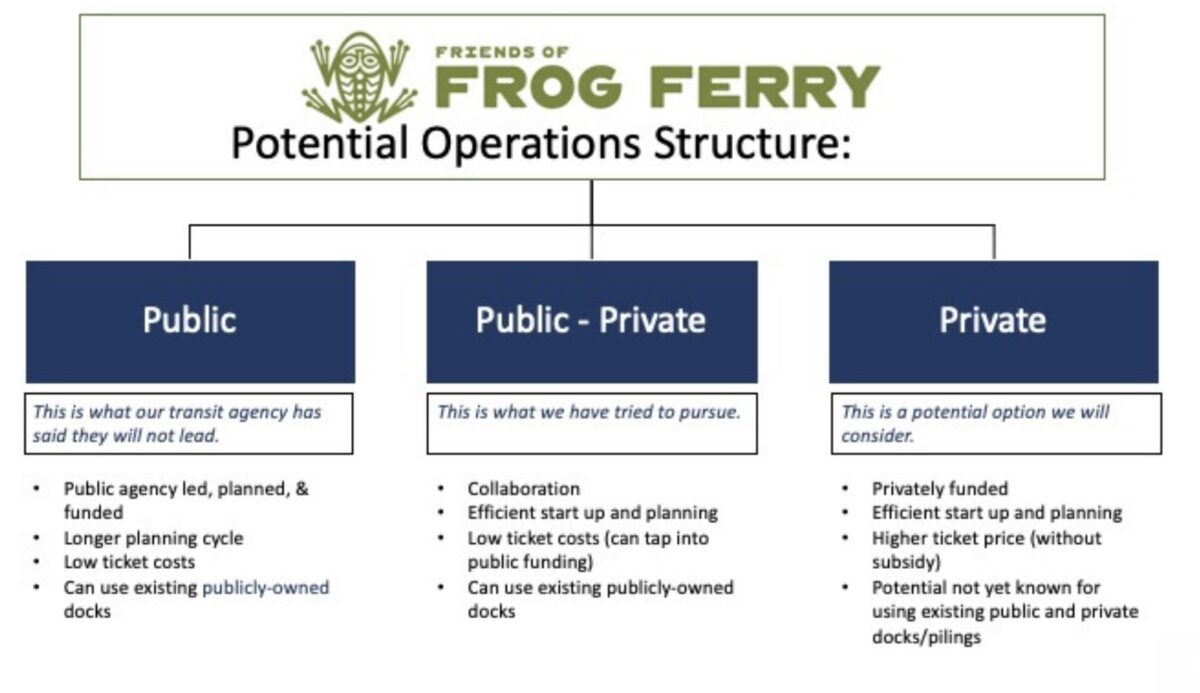

FOFF members, who have been advocating for this new transportation mode since 2018, needed a public agency – either TriMet or the City of Portland – to partner with them in order to apply for a Federal Transit Administration grant to develop the ferry pilot. That deadline came and went on Tuesday and Frog Ferry struck out.

The non-profit has received financial support from the City of Portland and State of Oregon the past; but local political will for the ferry project has fallen flat, and Frog Ferry leaders say they now have no choice but to put the program on an indefinite pause.

“We are able to a put a boat on the water within 18 months. We will not be able to do so until our City Leaders also make it a priority,” reads an email sent to supporters yesterday.

To FOFF supporters, this saga indicates the City of Portland is failing to innovate like it used to.

“Portland used to be a mecca for transportation innovation. If that’s a title that we were proud of, we’ll have to continue to evolve,” FOFF board member Nina Byrd told BikePortland on a phone call this morning. “[That evolution] requires robust transportation infrastructure, which includes a ferry system. It’s really not rocket science.”

But ferry-skeptical City of Portland leaders say they don’t have the bandwidth to take a project like this on right now. When Portland City Council discussed the ferry pilot back in April, Portland Bureau of Transportation Commissioner Jo Ann Hardesty appeared particularly wary of allocating resources to FOFF.

“I realize you’re interested in seeing PBOT tackle transport transformative transportation projects. The challenge is that the Bureau is already tackling numerous transformative transportation projects,” Hardesty said at the time.

Byrd said PBOT can do multiple things at once, and given that FOFF doesn’t need city money right now, all they’d have to do is help sign off on the federal grant application.

“This project has been seen as just an additional burden on behalf of our Bureau. I really do think it’s just a lack of sophistication in terms of bandwidth capacity,” Byrd said. “I get that, but it’s not an excuse to not innovate and to continue to grow our transportation system.”

However, Hardesty was also put off by a financial dispute between FOFF and TriMet, who was in charge of doling out the $500,000 in state funds to the ferry program. In April, TriMet officials wrote to city staff to express concerns that FOFF’s founder Susan Bladholm was asking the transit agency for questionable reimbursements. Bladholm has denied these allegations. To FOFF, TriMet is making up baseless accusations in order to withhold a chunk of the money allocated to the project.

“The level of scrutiny this project is under seems to be mired in political realities and personal opinion on behalf of our government leaders,” Byrd said. “[Accusations of financial impropriety] are nothing but absurdity.”

It’s not just the public agencies who are skeptical of the ferry proposal. Joe Cortright took his disagreements with Frog Ferry to City Observatory in April, writing that the ferry’s claims of expediency and practicality are outlandish.

“It’s not possible for a regular ferry service to travel faster between Vancouver and Portland than a car, or even today’s bus service. In the real world, boats are slower than both cars and buses,” Cortright wrote. “Water transportation, especially given the circuitous water route between Vancouver and Portland, the slow speeds of even “fast” ferries, the need to minimize damaging wakes at higher speeds, and the relative remoteness of docks from actual destinations, means that ferries in Portland are an unwise, uneconomic folly.”

But the FOFF concept will likely persist. Byrd told BikePortland the ferry is popular and inevitable in Portland, and even though the project is currently a sinking ship, they’re still asking for support.

“We believe that by and large, the majority of Portlanders are for the project. We believe there’s a pathway forward, but the public agencies have to step up and sponsor it,” she said. “We will have a ferry system one day. To say otherwise is like saying we’re not going to build another bridge or bike loop.”