When Oregon’s landmark “Bike Bill” passed in 1971, America was in the throes of a major bike boom. 50 years later a group of Portland bike advocates think our current cycling resurgence is the right time to update it

The nonprofit Street Trust has announced plans to seek an amendment to ORS 366.514. This law states “reasonable amounts” of the State Highway Fund must be spent by the Oregon Department of Transportation, “to provide footpaths and bicycle trails… wherever a highway, road or street is being constructed, reconstructed or relocated.” That “reasonable amount” is further defined as a minimum of 1% of the Highway Fund each fiscal year.

Advertisement

“The intent of the Bike Bill is to accommodate bicyclists and pedestrians in all road projects, but the vague statutory language gives the agency the discretion to determine reasonable amounts.”

— Hau Hagedorn, PSU masters candidate

This would be the second time The Street Trust takes aim at the bill. They (as Bicycle Transportation Alliance) sued the City of Portland in 1993 when construction plans for streets outside the Moda Center didn’t include bike lanes. The city argued it had met its obligation by spending 1% of project funds on biking and walking facilities. The Street Trust disagreed and won the lawsuit two years later. “The court concluded that the 1% figure is a floor, not a ceiling, for government spending on bicycle and pedestrian projects,” The Oregonian reported on March 11th 1995.

“This ruling says loud and clear that local governments have to consider everyone’s mobility needs when they build or rebuild roads,” said former Street Trust leader Karen Frost in a 1995 press release.

In an emailed newsletter today, Street Trust Co-director Tia Sherry wrote, “We are thrilled to be working on an update to the Oregon Bike Bill… Our amendment will aim to ensure that adequate sidewalks and bike lanes are included in every road or highway project in Oregon.” The amendment language has not been finalized, but the plan is to introduce a bill in the 2021 legislative session.

Advertisement

Street Trust Co-director Greg Sutliff shared with me earlier this month that the decision to amend the bike bill was informed by the work of former Street Trust board member Hau Hagedorn. Hagedorn, who’s currently associate director of the Transportation Research and Education Center at Portland State University and chair of the Oregon Bicycle and Pedestrian Advisory Committee, wrote a paper titled, “Policy Implications of the Oregon Bike Bill” (PDF) as a capstone project in her pursuit of Masters of Public Administration at PSU.

(Photo: TREC at PSU)

Hagedorn outlined several weaknesses of the law. She says ODOT uses loopholes to create substandard cycling facilities, isn’t spending nearly enough on biking and walking facilities to meet the state’s needs, and that there’s a lack of transparency and accountability in how the law is implemented.

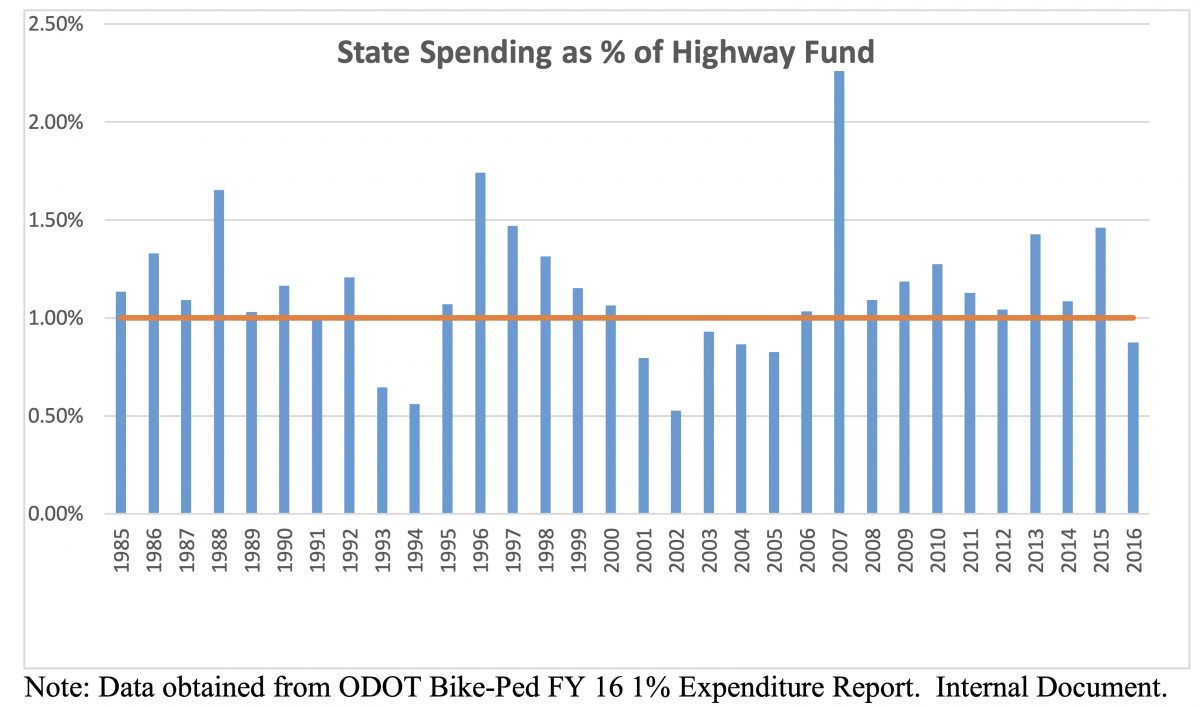

“The intent of the Bike Bill is to accommodate bicyclists and pedestrians in all road projects,” she writes, “but the vague statutory language gives the agency the discretion to determine reasonable amounts.” Hagedorn’s analysis of ODOT budgets revealed that in the past 30 years, ODOT has spent an average of just 1.1% of state highway funds on biking and walking infrastructure and did not meet the 1% requirement for eight of those years.

Hagedorn recommends boosting the legal funding requirement to 3%, removing vague language from the bill, creating clear design standards, and setting up an advisory board and performance metrics to make sure ODOT stays on course.

Sutliff with The Street Trust says the draft language of their proposed amendment will include all those recommendations. The proposal is currently in the office of State Senator Floyd Prozanski who plans to sponsor the bill. Prozanski is a long-time supporter of cycling issues. He was the chief sponsor of Oregon’s safe passing law for bicycle riders in 2007 and he successfully rolled the “Idaho Stop” law across the finish line in 2019.

— Jonathan Maus: (503) 706-8804, @jonathan_maus on Twitter and jonathan@bikeportland.org

— Get our headlines delivered to your inbox.

— Support this independent community media outlet with a one-time contribution or monthly subscription.

![It's official; Governor will look to expand Oregon Bike Bill [Updated] Buffered Bike Lane with a bike symbol and arrow pointing forward](https://bikeportland.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/bikeportland-default-thumbnail-3-300x300.jpg)

Thanks for reading.

BikePortland has served this community with independent community journalism since 2005. We rely on subscriptions from readers like you to survive. Your financial support is vital in keeping this valuable resource alive and well.

Please subscribe today to strengthen and expand our work.

I wonder what happened to that sweet bike?

And its appropriately outfitted with a transverse bag / saddle bag…true utility until panniers took over for most US riders.

Schwinn Paramont owned by Representative Don Stanthos (R) (?)https://www.oregonencyclopedia.org/articles/oregon_bicycle_bill/#.X9lIIC_r2i4 https://bikeportland.org/2011/02/24/read-the-letter-to-trimet-about-naming-new-bridge-after-don-stathos-48567

“My recommendation is to increase the minimum to match rates of federal funds expenditures at approximately 3%.”

1. The recommendation is entirely based on matching federal funds expenditures, not any other variable. 3% is incredibly low given that 99% for cars has been the status quo for decades.

“ODOT does not regularly publish performance metrics related to

the Bike Bill. Providing an annual report on implementation of the Bike Bill would

increase transparency and accountability.”

2. Without any goals, performance metrics are useless. The Bike Bill must have specific, measurable and attainable goals, updated quarterly.

“ODOT’s codification of highway shoulders as a minimum design standard for

bicyclists on urban freeways is problematic.”

3. Design standards must be clear and include “physically separated infrastructure” or they are meaningless.

“The language regarding exceptions can be clarified by removing “other available ways”. The term is vague and broad. Especially in urban areas, ODOT can easily point to the local street network that parallels state highways to exempt the agency from providing bicycle and pedestrian infrastructure on state highways.”

4. Remove language for exceptions entirely, and require ODOT to undergo an EIS and clearly designed community engagement and/or advisory board process.

I find it odd every time that ODOT, the most liberal state DOT in the USA, gets 100% of the blame for such conservative transportation funding policies in Oregon, when in fact it’s the governor and state legislature that is to blame, and the residents who keep electing them every election.

#1: The figure is closer to 90% for highways and 10% for other modes, including river dredging, ports, Amtrak services, rural bus subsidies, urban bus payroll tax, MTIP projects, etc. I agree it should be lower, maybe based on the percentage of deaths and serious injuries – maybe 70% roads, 20% pedestrian and bike infrastructure, the rest other modes, but that’s up to you and who you elect to your state legislature to represent your interests.

#2: ODOT has measurable goals concerning roadway speeds, congestion, and keeping their jobs, and while one could argue they are the wrong goals, it’s your conservative state legislature to set these goals.

#3: ODOT has built numerous separated bike/walk facilities such as the I-205 and I-84 paths in Portland, but how successful they are is open to question. The City of Portland also uses the parallel-street excuse to not put in PBLs and PBIs where they can get away with it.

#4: ODOT has a public engagement policy. That they use the OTC and JPACT isn’t all that different from PBOT using the Planning Commission, FAC, PAC, and BAC to rubber-stamp projects; both agencies often create CACs that are packed with handpicked pliable membership. The chief purpose of an EIS is to get area jurisdictions to sign off on a common project, which in the case of the Rose Quarter worked very well, as Portland signed off when the governor and state legislature needed them to, then the city tried to back out after it was too late, for an election. I agree it could be better, but I also know it could be a lot worse, and in most states it is worse.

Was Tom MCall the man or what?

Interesting. I wonder what the high dollar outlier years built in 1996 and 2007? All of this looks fantastic. This is absolutely the direction Street Trust should take. We cracked the State Highway fund for public transport, we backed ADA ramps, affordable housing. I hope we can get all of those same communities to get behind bikers for 10% not 3% of state funds. Go big or home!! Especially since bike growth has grown 30% we know we can hit even higher numbers of mode split. ❤️

We should add a statewide youth public transit pass. Get it from OHA for health impact on transport related social and economic justice for the young. They are all on the Plan anyways 😉

I find it a bit curious that they are going after such a heavy lift without clear leadership as they have neither an executive director nor a dedicated lobbyist. The legislative session starts in just over 3 weeks, time is short if they are going to move a bill like this. Opening the bicycle bill up could result in improvements but there is also the possibility that funding could become even less guaranteed than it is now and you can bet other groups will be lobbying heavily in that direction. Luckily the current makeup of the legislature makes me think it is unlikely that things would get much worse. On a related note the bike bill is also only as good as the enforcement and unfortunately the BTA/Street Trust ceded their status as watchdog when they decided not to sue ODOT over the lack of improvements to the St John’s bridge when it was overhauled.

This would be great if the city +/- the state actually used the funds to build usable facilities; I see empty, unused relatively new bike infrastucture all over the city; there is a major disconnect somewhere, and ‘updating’ the ‘Bike Bill’ will probably not change that.

One example of these empty new bike streets is on the Halsey/Glisan couplet. PBoT has built one of the better PBL designs next to a beautiful new park, but it is only a few blocks long, completely isolated, and reachable by riding the sidewalk only. The recently proposed Halsey design will hopefully fill this gap. I appreciate funds spent in E Portland. But this is why a network of PBLs in the inner neighborhoods should be its first priority, not an arbitrary assortment of streets sprinkled across Portland. The same applies to E Portland. Start with 122nd and build outward from that.

You might think it was more connected if you rode it. I have accessed it both from the new bike facility on 102nd as well as from the I-205 path(this connection through the fred meyer parking lot could be better but isn’t that bad). It does a nice job of getting you out east to N/S bike routes that can connect you into powell butte a ride I did just last week. It won’t all get built at once but there is more connectivity than you think out there, although it if you get off the network by a couple blocks it is pretty crummy for sure especially when crossing major streets.

Been there a few times. 102nd is a standard buffered bike lane alongside 30+mph traffic, something I would not recommend anyone in my family or friends to ride. It’s a great design for maintaining car capacity and speed, not safety. The few times I rode there, I witnessed people speeding in excess of 40mph passing and driving in the bike lane. So I stayed on the sidewalk.

I definitely agree the protection could be improved, although it is better than what it replaced, but I was speaking more to the connectivity. It isn’t a bike lane to no where IMHO.

Anyone know how Portland justified reconstructing inner SE Division, NW 23rd Ave south of Lovejoy, and constructed/reconstructed streets in the the Hoyt Yards development of the Pearl without bike facilities? What other streets has Portland constructed or reconstructed without pedestrian or bicycle facilities in the last 50 years?

Oh boy, where to start…

First of all, rebuild or build means you are removing the base material, sewers, water lines, etc, and replacing the whole thing – if you are “moving the curb”, you are rebuilding the road. But if you are grinding the pavement and adding a new layer of asphalt, that’s not a rebuild, it’s just repaving. Portland had done lots of that and has no legal obligation to put in bike facilities, sidewalks, etc.

Back in 2009 when I first started to help campaign for city-funded sidewalks for East Portland, we were repeatedly told a mantra by both PBOT and by Planning that all sidewalks in Portland were put in by either developers or by homeowners; that we needed to form an LID (local improvement district) to tax local homeowners and businesses to build sidewalks; and that neither PBOT nor its pre-1988 predecessor Department of Public Works had ever EVER built any sidewalks using public funds. Yes, ODOT and the county had done it on occasion, but not the City of Portland. Sometime in 2010 I was at a budget meeting at PBOT, again vainly advocating for city funded sidewalks, again got the usual mantra, when suddenly a bridge engineer who had no skin in the conversation brought up a report that PBOT staff had done in 2000 in which they laid out the history of sidewalk construction in Portland, including all the many instances that PBOT and Public Works had in fact built sidewalks at public expense, usually in rich areas of town.

Long story short, if you live in inner Portland, there’s a very good chance your sidewalks were put in by early developers and homeowners long before the street was paved, often decades before – there was a stone-lined trolley but otherwise no pavement. The earliest street pavement was paid for by bicycle subscribers who wanted paved tracks for their bikes starting in the 1890s; most streets didn’t get paved for cars until after the First World War. The city likely built the sidewalks along major highways like Sandy, McLaughlin, Naito, and Barbur before ODOT had even been formed. After WW2, unincorporated parts of the city had sidewalks in richer neighborhoods, put in by developers to attract wealthier buyers, such as in Cherry Park and Argay. Almost all the bike lanes in East Portland were put in by Multnomah County in the 1980s before annexation (1986-1991), on arterial streets where on-street parking was completely banned, at a time when inner Portland had nearly no bike lanes at all. After annexation, PBOT removed traffic lanes in East Portland and added parking lanes, but didn’t do any sidewalk infill until we got on their case 20 years later, and only because Mayor Adams was breathing down their necks and found money during the Great Recession by delaying bond payments on the Sellwood Bridge.

As for on-street bike facilities on streets built or rebuilt since 1970, any street rebuilt by ODOT should have had bike lanes added, and they in fact did so within the Multnomah County areas and in Gresham, but PBOT kept preventing ODOT from adding bike lanes within the city, including on inner Powell, McLaughlin, Lombard, and 82nd. 82nd south of the city, in Clackamas County, actually does have bike lanes. The Barbur lanes were added later.

In part sometimes the city and or ODOT violates the bike bill and nothing happens because the remedy is for someone to sue. There was a time when that someone might have been the BTA but there hasn’t been an organization with the money, know how, and desire to file a suit in some time. I was surprised that there wasn’t a lawsuit over the St. John’s bridge. https://bikeportland.org/2006/06/15/st-johns-bridge-still-unsafe-after-75-years-1486

Thank you Hau Hagedorn and The Street Trust for your work on this!