(Image: Google Street View.)

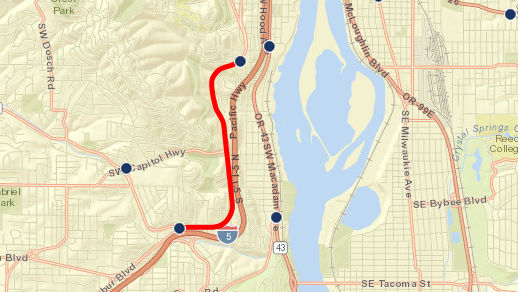

During a construction project last summer, the Oregon Department of Transportation seems to have discovered that there’s a way to cut extreme speeding on a curving two-mile stretch of Southwest Barbur Boulevard where six people have died in the last five years.

Was it closing the passing lanes? Lowering the posted speed limit from 45 to 35 mph? Upping traffic enforcement and penalties? Simply marking it as a construction zone?

The agency did all of those things at once, so it isn’t sure which one worked, and it currently has no plans to find out.

Meanwhile, the state-owned street has returned to normal indefinitely.

At a neighborhood meeting on Wednesday a state spokeswoman said that ODOT is reluctant to restripe the street with one less passing lane because, in part, all lanes would be needed if Interstate 5 collapses in an earthquake.

Safety was ‘not the focus’ of state analysis

(Photo: J.Maus/BikePortland)

Four ODOT staffers visited the Southwest Neighborhoods Inc. transportation committee last night to discuss an ODOT study of traffic patterns during last summer’s construction project.

But they didn’t discuss the apparent safety benefits of the project, which had also been illustrated by the data they gathered, because they said they hadn’t been assigned to assess safety.

“It’s really not the focus,” said Chi Mai, a senior traffic analyst and modeler for ODOT. “Our focus was to look at the average [traffic speeds and volumes] and compare them.”

Among those who called for ODOT to assess immediate safety improvements to Barbur were Lewis and Clark College, the City Club of Portland, Oregon Walks, the Bicycle Transportation Alliance and Portland Transportation Commissioner Steve Novick.

By examining those averages, ODOT determined that during the Tuesday, Wednesday and Thursday morning traffic peak, removing a lane from that two-mile stretch slowed the typical northbound car by an average of 68 seconds, with the most congestion between 8:15 and 8:45 a.m. The agency also found that the rush-hour slowdown led to no observable diversion of cars onto Terwilliger Boulevard or other alternative routes.

“The consistency was surprising,” said Jacob Skugrud, an analyst on ODOT’s major projects team.

Advertisement

We wrote about these findings in our coverage last month.

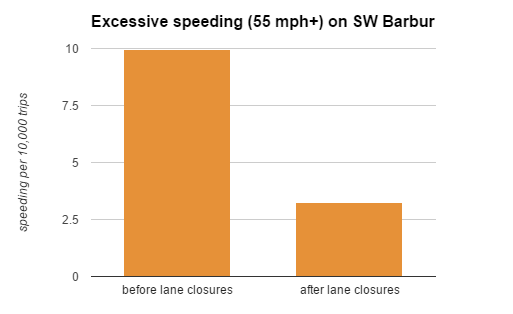

As we also reported at the time, the proportion of observed northbound drivers whose speed was 55 mph or faster fell 68 percent during the construction work: from about 10 drivers per 10,000 to about 3. This was based on electronic devices that detected Bluetooth signals as they passed two different points on the roadway, two miles apart.

But ODOT spokesman Don Hamilton said Thursday that ODOT’s usual method of measuring travel speed is to measure exact speed at a single location, so the Bluetooth travel time data couldn’t be used to draw conclusions about speed patterns.

“You take it from a single point, not between two,” Hamilton said.

Hamilton also said that speed data is “not accurate in an area where there is significant construction” because he believes people slow down in construction zones even without any changes to passing lanes, speed limits or enforcement.

ODOT: Any lane changes require regional consensus

(Click for data)

Susan Hanson, ODOT’s interim community affairs manager, said Wednesday that “more research” about safety would be needed “when this is discussed more broadly.”

She suggested it would be unlikely for ODOT to discuss changes to Barbur Boulevard more broadly except in the context of the Southwest Corridor Plan, which isn’t expected to result in any construction until 2021 at the soonest. This long-term plan to add rail or bus lanes on Barbur is fiercely opposed by public transit opponents in other cities, who have so far passed two ballot issues designed to stall or block the idea.

Hanson said that although this stretch of Barbur Boulevard sits within Portland city limits, the agency will not redesign the road without the agreement of other nearby cities.

She said that’s because it is a freight route that runs parallel to Interstate 5. Therefore, Hanson said, Barbur functions as “a seismic lifeline if I-5 goes down” and also as spillover in the case of major crashes on Interstate 5.

Some improvements made for biking and walking

(Image: Portland State University PORTAL system)

Also at Wednesday’s meeting, ODOT Transit and Active Transportation Liaison Jessica Horning discussed the agency’s efforts to improve sidewalks, and crosswalks and incomplete bike lanes up and down Barbur. Within the two-mile stretch in question, the agency has recently added flashing “bikes on roadway” beacons and a green-painted bike lane where Barbur meets Capitol Highway.

In 2012, the state also added a crossing beacon near the site of the 2010 fatality of a woman walking a bicycle.

Burke, 26, killed by a speeding driver

in 2010 while walking her bike across

Barbur to her apartment building.

The other five people killed on this two-mile stretch of Barbur since 2009 were in cars and on a motorcycle.

The Bicycle Transportation Alliance has circulated a petition to request that ODOT restripe this two-mile stretch of Barbur to remove a northbound passing lane and instead add protected bike lanes and walking paths on each side.

At Wednesday’s meeting, Kiel Johnson of the neighborhood advocacy group Friends of Barbur asked Mai how many collisions would be required before ODOT considers restriping Barbur immediately.

“Our traffic safety group would have to answer that kind of question,” Mai replied. “That’s not something that we work with enough to say.”

Thanks for reading.

BikePortland has served this community with independent community journalism since 2005. We rely on subscriptions from readers like you to survive. Your financial support is vital in keeping this valuable resource alive and well.

Please subscribe today to strengthen and expand our work.

The agency will not redesign the road without the agreement of other nearby cities because Barbur is “a seismic lifeline if I-5 goes down.”

Now ODOT’s Susan Hanson has gone beyond excuses and moved to outright lies. In the event of a major earthquake, paint on the road is not going to stop emergency vehicles or any other sort of short term reconfiguration. This is just insulting. I can’t wait until ODOT is completely out of Portland street management.

I-5 will be covered in rubble after an earthquake. That rubble will be former Barbur Boulevard.

Anything big enough to ‘take down I-5’ is probably going to take down a lot more. Barbur has bridges in many places. Also, restriping doesn’t preclude an emergency re-stripe to provide auto capacity in the event of a catastrophic event. Thought I recall NYC shutting down access to most autos in 2001 and people walking and biking over the major roads. Certainly buses would be more efficient if lane capacity is severely restricted.

Firefighters ran through the tunnels under the Hudson River when 9/11 took place.

Yeah I suspect that the Capital Highway overpass/on ramp would fall long before I-5 would become impassable.

As a publisher/editor I’ll say I am looking forward to us doing more reporting on this story.

As a Portland resident who uses a bike as my primary mode of transportation, I’ll say I am very concerned at ODOT’s seeming unwillingness to improve the design of this street despite clear support from the community, favorable modeling data, and their own claims to being an agency that wants to look beyond the outdated and dangerous status-quo that puts driving convenience and efficiency above everything else.

ODOT: If not here, where? If not now, when?

ODOT:

We are robots.

We don’t think.

We do not answer sensible questions.

Next?

It’s almost as if they are arguing for eliminating their design budget. If they can’t do something here, then why bother even doing what they do?

This isn’t just a bike issue. Most of the people killed on Barbur are motor vehicle operators.

complete joke. angered. furious.

Something that might be worth following up on is that other parts of ODOT besides Region 1 seem to be capable of dealing with safety issues. Remember the response to the HWY 101 paving screw-up?

The HWY 101 paving screw-up wasn’t about safety (from ODOT’s viewpoint), it was about egg-on-face, about being caught with their parameters down by someone with a good rolodex.

Any interest in a “Die-in” / “Stop de Kindermoord” style protest in front of ODOT Region 1 offices in downtown?

I used to ride that route every day during college. Not so often now unless i ride out to my mothers place. I dont see what the big deal is. It works fine. Terwilliger is right up the hill if you want a safer, slow car experience. Barber is fine for bikes and cars as it is. It was a disaster when they reduced the speed limit. It breaks traffic flow for the entire sw.

More data is needed for me to finish this comme

ODOT is capable of changing traffic flow on a dime – in the event of a crash on the highway, for example, they can have signs, cones, etc. on site in less than an hour. I find it hard to believe that in the event of a major disaster, they could not find a way to overcome painted strips on a road.

“…a curving two-mile stretch of Southwest Barbur Boulevard where six people have died in the last five years. …

…In 2012, the state also added a crossing beacon near the site of the 2010 fatality of a woman walking a bicycle. The other five people killed on this two-mile stretch of Barbur since 2009 were in cars and on a motorcycle. …” andersen/bikeportland

Just one person out of the six killed in collisions on the road, was a vulnerable road user. And what was the reason discovered, that the other five people in their cars and on their motorcycle crashed and died? The reason was people irresponsibly operating their vehicles beyond what their vehicles and the road were designed for.

This does not make much of an argument for the road diet idea requiring removal of one of the road’s main lanes, the main objective of which is to re-purpose some the road’s right of way to close a couple gaps in the road’s bike lane, where it crosses the road’s bridges.

“The reason was people irresponsibly operating their vehicles beyond what their vehicles and the road were designed for.”

So if the reason is just drivers being irresponsible, why does it happen so often on Barbur and not nearly every other road in Portland?

“…why does it happen so often on Barbur and not nearly every other road in Portland?”

One death on the road per year of a person driving that doesn’t drive their motor vehicle responsibly, isn’t an often occurrence. Reducing the two lanes of north bound Barbur traffic to just one, does not seem likely to stop the kind of driving that led to those deaths.

People wanting continuous bike lanes on Barbur, and a road diet, will most likely have to find a more convincing argument than attempting to suggest that deaths on this road occur often.

More than one death per year on a 1.5mi stretch of road? If that same rate was seen in the rest of the region, we would have thousands of people dying in the metro area each year. And the data on speeding is right there in the article. Keep sticking your head in the sand.

Look beyond the attention seeking story headlines, and the inflated rhetoric about the road being ‘dangerous’, and it’s apparent the road’s design isn’t particularly dangerous at all. The deaths are due to occasional examples of people taking advantage of the road’s relatively uninterrupted stretches, to drive badly. Specifically, late nite DUI speeding.

Aside from isolated example of this kind of bad driving, many hundreds of thousands of people use this road with few problems. I think, that in fact it’s because people are able to use the road with few problems, that they use the road whether driving or biking.

Of course the road could be quieter and more welcoming to use with a bike, and this could possibly be accomplished without resorting to a road diet, by working for lower posted speed limits, and using various means of discouraging speeding. Those approaches likely have as much chance, likely more, of being implemented, than does a road diet.

Personally, I’d say to people biking that don’t want to deal with Barbur’s motor vehicle traffic: Ride Corbett. It goes in and out of town, from Burlingame. Hillier for sure, but far more quiet and peaceful to ride. Barbur isn’t likely to become anything remotely like a peaceful esplanade for biking, anytime soon. Even with the road diet, it’s still likely to continue being a noisy, dirty ride.

But Bob, what’s not counted is the people (largely a substantial size) who won’t even use the road with its current format. And this is (and should be) the MAIN way into downtown from the SW. Forcing people (who don’t have the luxury of motors) onto hillier routes isn’t a great solution, esp. since the more people biking, the less auto traffic there would be anyway. If anything shouldn’t the people who travel without having to exert any physical effort be the ones routed on the hillier roads?

Bob the big question is why would you want to keep the road as is? ODOT and Portland have acknowledged that it is more dangerous than it should be (despite your objections). And the traffic counts over the last decade have shown a steady decrease in drivers. Why continue to use an unsafe, overbuilt road? To save a minute for some drivers during rush hour? To not rock the boat at ODOT?

“…Bob the big question is why would you want to keep the road as is? …” davemess

If you consistently read comments I’ve posted about this subject, you’d know that I don’t think that Barbur should necessarily be kept as is. Reduced posted speed limits, electronic speed monitoring and citation issuing, are some ideas having occurred to me to apply to the road. I’ve also thought of temporarily reconfiguring the road to a road diet for a true test period.

I tend to think that stepping up efforts to reduce speeds, short of reconfiguring for a road diet, would be better first steps towards a road environment more hospitable to biking.

Except that’s denying the fact that Portland has TERRIBLE track record with speed enforcement. I don’t think they’re just going to get it together for Barbur.

Wsbob, you’re right that removing a northbound passing lane wouldn’t eliminate the possibility of very-late-night zooming, let alone of drinking. What the state’s data shows, with surprising precision, is that half of the extreme speeding is actually happening in hours when there is other traffic on the road. Those are the stupid behaviors – traffic weaving – that became much rarer when the passing lane went away.

Michael, your story headline refers specifically to deaths occurring on the road over a period of five years. Those deaths were due to bad driving, rather to defect in the road’s design.

If the time of day the collision producing deaths occurred was when there was other traffic on the road, (generally daytime commute hours is what I presume you’re referring to.), that’s something to consider. I don’t exactly recall what times of day the collisions in question occurred.

Five of the six deaths since 2009 were coded by the state as being speed-related (the notation is 30; you can search for “fat” to find fatalties in that sheet). They occurred at 10 p.m., 6 p.m., 2 p.m., 3 a.m., 4 a.m., and 10 p.m., respectively.

The only one that wasn’t speed-related was the 2 p.m. collision, in which a woman unexpectedly crossed the center line and hit a truck. It’s anybody’s guess why that happened or whether she’d be alive if Barbur felt more like a city street in this stretch and less like a freeway.

Lots of nonfatal crashes in the same period, of course, but you’re right that I don’t mention them in the headline.

You apparently do not understand the connection between road design and “bad driving”. So you must think that the United States has over 30,000 road deaths per year because we are bad drivers? Or is it lack of enforcement? Why do people here die at rates 2-3x higher than other developed countries?

Barbur Boulevard on a diet would look less like a freeway with dashed lane lines (this is where you go fast, pass vehicles, drift back and forth from lane to lane) and more like a street (this is where everyone goes the same speed).

Of course, the speeders will probably go eat death in the Terwilligers. Maybe it’s not so much about saving lives, but about claiming the adjacent right-of-way for another use.

Not having the stomach for dealing with transit-hating suburbs is spineless, but I get it.

It’s deeply troubling that if there is a SUPER EMERGENCY CRISIS, a feckless ODOT will be unable to handle stripes on the road. And under what scenario would I5 be taken out, yet leave Barbur as a serviceable backup?

It’s hard to keep a conversation going until 2021, but that’s what it’ll take.

the pessemistic side of me thinks that the suburb’s response will be, “Barbur lane closure? Well, I never drive it or ride my bike on it, but I vote no.”

PBOT underwent a major lane reorganization on their stretch of Barbur a few years back, reducing 2 southbound lanes into 1 with a center turn lane and adding a buffer to bike lane. I don’t recall them having to get approval for Tigard or Southwest Corridor Plan to do this.

“ODOT is reluctant to restripe the street with one less passing lane because, in part, all lanes would be needed if Interstate 5 collapses in an earthquake.”

RIDICULOUS excuse

WTF, ODOT, WTF.

This meeting was especially disappointing considering Steve Novick’s pledge to study a barbur road diet “within 12 months” in his letter to “road dieters” he sent out last october. Apparently no study has taken place.

So if there’s an earthquake, we’re expecting I-5 (which just so happens to cross the one bridge over the Willamette that a recent PSU analysis showed could survive the “big one”) to be impassable but having that extra capacity on Barbur will save the day? Riight.

The arguments against a Barbur road diet have become so hamheaded and half-hearted that I’d bet even the people making them don’t believe them.

Where’s that study? I know that Marquam has cable ties, but I don’t think it’s rated above a 6.

Yeah, those cable ties were part of a recent-ish seismic retrofit. I couldn’t find the original documents with a quick Google but there are several stories from the media covering as much, like this one from KOIN.

http://koin.com/2013/05/24/how-safe-are-the-bridges-of-portland/

I was in Pomona during the Northridge, CA, quake and working at LAX. On the newer overpasses, the roadways fell but many columns remained in tact. On the older highways it was the other way around. The road failures were because the columns crumbled – the concrete was pounded into small cobbles and fell away from the reinforcement. Much of the retrofit for bridges involves wrapping the columns with a plastic reinforced fiber, glass or carbon, to prevent the pieces of concrete from falling away from the rebar. It would still need to be replaced, but it would survive enough that the roads would not fall down.

The overpasses at Corbett, Terwilliger, and 19th will all probably come down when the big one comes, blocking I-5 before reaching the Marquam Bridge from SW.

Still not relevant to lane diet, though. I don’t think people are going to be concerned about their morning commute at that time, for one, and emergency lanes could be setup regardless of a lane diet.

This is a critical article; one that sets up a perfect campaign.

As Jonathan noted, this is a perfect example of the culture so ingrained at ODOT (and the public and freight community at large).

It’s as if the traffic engineers, etc. just can’t understand why people aren’t focused on traffic throughput instead of lives being lost.

Anytime ODOT claims safety is its number one priority this needs to be brought up as Exhibit #1 as why that’s simply not true.

Hopefully BikePortland, the BTA, Steve Novick, the City Club, and the community will get it done. Unfortunately, there’s some worry that the suburban leaders (note the “regional consensus” reference) will try to spike it. They also need to be held responsible if they resist making this a safer place for all to travel.

As an automobile user, it’s blatantly obvious ODOT doesn’t care about my life when I get behind the wheel and traverse the streets.

As if crash corner is working extremely well in Raleigh Hills?

That earthquake excuse is laughable and insulting and just about everything but the truth, all at the same time.

Thank you for your continued coverage and support for safety improvements along this stretch of Barbur including in your podcasts, which I highly recommend.

Although the area studied by ODOT (thanks primarily to PBOT) was between Bertha and Hamilton the only section in need of a lane reduction for safety is from SW Miles to Hamilton. Other than the southern side of the road between the on/off I-5 ramps and Terwilliger, which is in desperate need of a sidewalk and pedestrian improvements and improved (protected?) bike lane markings on either side there is no need for a lane reduction. This is a very common misconception and I am baffled as to why the study was even considered or thought to be useful west of Terwilliger. I can only guess they also wanted to measure additional overflow/backups, which almost never occurred.

Has ODOT or the Freight Committee(s) thought to consider for even a moment a safer roadway for people using alternative modes would mean less traffic in current configured lanes and therefore faster, more efficient motorized travel for commercial vehicles and suburban commuters?

Is the sacrifice of actual and perceived (wsbob) safety for vulnerable road users 100% of the time worth the minute “saved” by motorized vehicle users less than 5% of the time? Travel Barbur at 10AM, 2PM, 7PM-6AM and you will likely see what I do 99% of the time during those hours. An asphalt, lifeless desert of a roadway that still feels dangerous to walk or bike on.

Has anyone from the state ever checked out the tremendous views from those bridges? Wouldn’t it be nice to see people enjoying them regularly?

Kiel, thanks for attending the SWNI meeting. With all due respect

Friends of Barbur is not a neighborhood group. It has been it’s own entity with a stagnant facebook page and website. My guess is a simple name change to People for a Safer Barbur Blvd (or something similar) would resonate more rapidly throughout the community and make a much greater impact. Honestly, it is difficult enough to be a friend of a creek or a tree, much less a dangerous roadway. Barbur does not have friends and should not have friends in it’s current state. Please consider this change and see what happens!

When Tilikum opens many will wonder why there is an active mode wall (Barbur Blvd) just west of the Gibbs St. Bridge.

Friends of Barbur were at a late 2014 meeting for the monthly SW Trails meetings.

“…Is the sacrifice of actual and perceived (wsbob) safety for vulnerable road users 100% of the time worth the minute “saved” by motorized vehicle users less than 5% of the time? Travel Barbur at 10AM, 2PM, 7PM-6AM and you will likely see what I do 99% of the time during those hours. An asphalt, lifeless desert of a roadway that still feels dangerous to walk or bike on. …” Phil Richman

If you’re seeking actual and perceived safety for vulnerable road user on Barbur, ask for slower posted speed limits, and, or speed limit control vans to help rein in people driving irresponsibly. A road diet isn’t likely to accomplish that.

Road diets are often accompanied with a speed limit reduction though. Do you have any data showing road diets don’t alter speed patterns?

All data I have seen shows a reduction in speed. http://safety.fhwa.dot.gov/provencountermeasures/fhwa_sa_12_013.cfm

“Road diets have multiple safety and operational benefits for vehicles as well as pedestrians, such as: Improving speed limit compliance and decreasing crash severity when crashes do occur.”

“In addition, based on a separate study of one site in Iowa, there appeared to be a traffic calming effect that resulted in a 4–5 mi/h reduction in 85th percentile free-flow speed and a 30 percent reduction in the percentage of vehicles traveling more than 5 mi/h over the speed limit (i.e., vehicles traveling 35 mi/h or higher).”

Knapp, K. and Giese, K. (1999). Speeds, Travel Times,

Delays on US 75 4/3 Lane Conversion through Sioux

Center, Iowa during the AM and PM Peak Periods.

Iowa State University/Center for Transportation

Research and Education for the Iowa Department of

Transportation, Ames, IA.

“Road diets are often accompanied with a speed limit reduction though. Do you have any data showing road diets don’t alter speed patterns? …” davemess

What I’m saying, is that if a reduction in top travel speed on this highway, Barbur Blvd, is one of the top changes sought, then ask for that to be accomplished more directly than a road diet likely would be able to. Ask that the posted speed limit be dropped from where it is presently. Ask for speed limit vans and photo radar equipment to positioned along at changing points along the road, to record and cite people driving that exceed the speed limit.

Constricting the road’s three main lanes from four to three, requiring traffic to at some point, change flow rate to merge from two lanes into the one, mainly so the roads’ bike lanes can be made continuous over the 100′ or so each, of the road’s two bridges, and then change back, doesn’t sound like a very good idea.

Too much moving back and forth of traffic consisting of the by far, most prominently used mode of travel travel on the road, motor vehicles. Traffic situations requiring that kind of back and forth movement are an added complication and an additional hazard. Better to keep traffic flowing down the road slowly and simply with a minimum of lane changes. If the posted speed limit were to be reduced, and vehicle speeds maintained by various means to no higher than 5 mph over that speed, that could create a situation for people biking that would allow them to much more easily merge from the bike lane and into main lane traffic for travel across the bridges. A road diet, which really, is being sought just to create room for continuous bike lanes over the bridges on the road’s limited width, may not be needed.

“Constricting the road’s three main lanes from four to three, requiring traffic to at some point, change flow rate to merge from two lanes into the one, mainly so the roads’ bike lanes can be made continuous over the 100′ or so each, of the road’s two bridges, and then change back, doesn’t sound like a very good idea.”

But a road diet is EXACTLY something that has been proven to slow speeds down (regardless of what the speed limit is). Infrastructure has shown to have a bigger impact than just changing the speed limit (as we all know PPB does not do an adequate job of enforcing speed limits).

Portland has shown a strong interest in road diets recently, and the increase in crashes (that you’re proposing) has not happened. In fact the opposite has. The roads have gotten safer than they were.

“…But a road diet is EXACTLY something that has been proven to slow speeds down (regardless of what the speed limit is). Infrastructure has shown to have a bigger impact than just changing the speed limit (as we all know PPB does not do an adequate job of enforcing speed limits).

Portland has shown a strong interest in road diets recently, and the increase in crashes (that you’re proposing) has not happened. In fact the opposite has. The roads have gotten safer than they were.” davemess

Barbur has never had an actual road diet configuration over the section of the road where the bridges are located. It’s questionable whether on this highway, an actual road diet, rather than a construction zone standing in for one, will stop the type of death producing driving that has occasionally occurred on the road.

Enforcement of speed limits could possibly be administered more practically, with speed limit cameras, etc.

I have provided links and data showing that road diets can and do reduce speeds. You are hypothesizing that a road diet won’t work with no data. I guess we’ll leave it at that.

Absurd. If I-5 collapses in an earthquake, we have bigger problems than suburbanites getting to work on time.

I’m apoplectically furious over this. So ridiculous. How long and loudly have advocates asked for this as part of the assessment during construction?

I believe “can’t do it because earthquake” is a new square on the PBOT/ODOT lack-of-action bingo card.

Particularly when coming from an organization that was ready to drop a billion dollars on a freeway expansion mega-project rather than retrofit its existing roadways to prevent damage during earthquakes.

Conflating PBOT and ODOT is an insult to PBOT.

Since ODOT doesn’t understand that people dying on Barbur is a problem, why not advocate with the police to do a better job of enforcing speed limits of cars on Barbur? That is something Portland police could do – and would not require action from ODOT.

PPS/Traffic doesn’t have much of an overnight crew to enforce speeds. This is an area of VZ/Safe Systems the *city* needs to focus more attention on (traffic enforcement). Changing road space allocation alone won’t have much effect between midnight and 5 AM on speeders. The city budget in this area is inadequate to the point of negligence.

I rode Barbur today and saw a metal lock cord in the “bike” lane. So much debris on Barbur, moms walking with zero shoulder on Babur in the SW 18th block.

You can write Susan.C.Hanson@odot.state.or.us (with polite and diplomatic lanaguage) about how ODOT has made it clear that safety is not their priority for Barbur Boulevard. If safety was their priority, they would more seriously consider protected bike lanes and improved sidewalks.

https://docs.google.com/forms/d/1pI5w8Fmf7YMVQ_MJ0o_PU27pDhgPX0X3nLObHiz8gIg/viewform?c=0&w=1

Here is the message I sent:

Disappointed in Southwest Neighborhoods Inc. Transportation Commitee meeting from yesterday, because ODOT does not appear committed to safety improvements on Barbur that Lewis and Clark College, the City Club of Portland, Oregon Walks, the Bicycle Transportation Alliance and Portland Transportation Commissioner Steve Novick have all called for.

To prevent further traffic deaths and injuries, ODOT should seriously consider potential solutions such as those proposed by the BTA:

https://docs.google.com/forms/d/1pI5w8Fmf7YMVQ_MJ0o_PU27pDhgPX0X3nLObHiz8gIg/viewform?c=0&w=1

Thanks for your consideration,

Josh Gold

driver, bicylist and pedestrian

Portland resident

I was hopeful for Barbur after the concise construction reporting last month, but now I feel Barbur is falling in line with the 2030 Bike Plan, Vision 0, Street Fee, 20’s Bikeway and Clinton Diverters. Feeling hopeless.

Today on a bike, north-bound on Barbur today at roughly 10:30 AM, zero cars passed me while I was going 17 mph between SW Brier Place and SW Capitol Highway. Zero cars were anywhere close to me traveling north across the Barbur bridges. Most are on I-5.

Well at least the ODOT staffers in attendance at the meeting were honest in what their priority (and I assume their supervisors priority) for this corridor is:

“But they didn’t discuss the apparent safety benefits of the project, which had also been illustrated by the data they gathered, because they said they hadn’t been assigned to assess safety.

‘It’s really not the focus,’ said Chi Mai, a senior traffic analyst and modeler for ODOT. ‘Our focus was to look at the average [traffic speeds and volumes] and compare them.’ “

It is the old capacity capacity capacity.

Please would a traffic engineer / or technician comment about the methods of traffic speed measurement (spot, vs journey or running speed) and the utility of the data collected vs ODOTs now desired data [as discussed by ODOT’s PR staff]:

“But ODOT spokesman Don Hamilton said Thursday that ODOT’s usual method of measuring travel speed is to use radar guns at a single location, so the Bluetooth travel time data couldn’t be used to draw conclusions about speed patterns.

‘You take it from a single point, not between two,’ Hamilton said.

Hamilton also said that speed data is ‘not accurate in an area where there is significant construction’ because he believes people slow down in construction zones even without any changes to passing lanes, speed limits or enforcement.”

Hamilton’s comment about the effect of construction on travel speeds has its greatest effect on spot speeds if the spot speed is close to the construction zone…so thus would not journey or running speed not be a better proxy measure of how a future corridor may function? [Chime in traffic engineers or technicians…if I have this wrong.]

Journey/running speeds are now commonly used for police enforcement of speeding in many countries and concurrency studies…because of the known short comings of spot speed measurement.

If spot data was so important to ODoT, why did they not take spot measurements with “radar” during the construction period. They knew this was going on…and would be discussed.

Since you’re asking specifically for feedback from a traffic engineer here I’ll take a shot at this, but I think it’s useful to first take a step back and look at what traffic engineering actually is.

One way to describe engineering might be to say that it’s the practice of applying the scientific method to try to solve a specific problem or accomplish a specific task. Note that this distinguishes engineering from pure science in a critical way: Scientists ask more general questions about how the universe works and will largely follow evidence wherever it leads, while engineers have a specific goal in mind at the outset, i.e., an agenda. Often that goal is obvious and noncontroversial, and success is easy to define. If the bridge does not fall, the structural engineer has succeeded. If the rocket deposits its payload into the proper orbit, the aerospace engineer has succeeded.

So what about the traffic engineer? What is our goal, and how do we know if we’ve succeeded?

Traffic engineering is a relatively new field that began to arise as something distinct from other branches of civil engineering during the go-go era of road building in the middle of the 20th Century. At that time, the amount of driving correlated nearly perfectly with economic output, and so the massive expansion of our auto infrastructure that occurred in the three decades after WWII was the backbone of the rapid economic growth that occurred during the era. In 1950, the first Highway Capacity Manual was published, which standardized the methodology for quantifying throughput of vehicles. Fifteen years later the first edition of AASHTO’s “green book” was published, standardizing many elements of highway design to ensure efficient traffic flow. Thus the profession was born, complete with its original sin: It would concern itself with throughput and travel times for motor vehicles, and little else. The goal of traffic engineering—maximizing throughput and minimizing delay—would remain the same and would not be seriously questioned for decades.

Today, of course, things are changing, and changing rapidly. The profession has largely rebranded itself as “transportation engineering,” and many if not most of us are asking a different and more complicated set of questions. Instead of, “How do we maximize throughput and minimize delay?,” we’re asking, “How do we maximize safety? How do we maximize the utility that a street can provide to its community?”

Of course, the old attitude is far from dead. Allowing for exceptions to every rule, the capacity-first engineers tend to be older (and thus have more seniority and more power) and tend to work for state DOT’s (which, generally, were formerly called “highway departments”) rather than cities. Exacerbating the problem, measuring capacity is a relatively easy thing to do from an analytical standpoint, especially given the 65 years of refinement and standardization of the practice. Safety, by contrast, is far, far harder to quantify and attempting as much has a far shorter history; the first Highway Safety Manual was published in 2009, nearly 60 years after its capacity-concerned counterpart.

In this context, everything coming out of ODOT makes sense and has been consistent from the get-go. ODOT continues to practice this old-school style of traffic engineering, where they’re concerned primarily or even exclusively with automotive throughput. The question they asked over the course of this study is, “How might a Barbur road diet affect capacity and delay?” This is what informed the methodology they used to collect speed data—calculating an average speed over a distance is a direct measurement of travel time. Calculating instantaneous speeds at a particular point really reveals no useful information regarding travel time. While we know that speed and crash risk/severity are directly related, and thus a before/after measurement of speeds at a given point on the roadway might be an excellent proxy for teasing out safety effects, ODOT simply isn’t interested in answering this question. This is an agency, after all, that recently claimed that road design doesn’t influence safety. The engineers there still view their job as one of maximizing throughput to accommodate economic growth. Since nearly all crashes have an element of human error, they can simply shrug and label them “accidents”—occurrences that become statistically inevitable as volumes increase.

That the study was designed to measure exclusively the delay and capacity effects of the road diet makes it harder, but by no means impossible, to use the findings to answer broader questions about the safety and utility of the street. But this clash of old-school and new-school thinking is something that plays out over and over again in any number of ways in my profession. This is what informs much of the analysis I’ve written on this (how do we do an apples-to-apples comparison of delay costs and safety benefits?) as well as my constant push-back against use of the term ‘accident’ and other symptoms of engineers being lazy in their analysis of safety implications.

With this in mind, Mikael Colville-Andersen, Jeff Speck, and their ilk have concluded that traffic engineers are The Problem, but this is simplistic. I believe that transportation engineers have a crucial and unique role to play in fixing our streets, provided we can start asking (and then seeking to answer) the right questions. ODOT has clearly asked and sought to answer the wrong ones here. While I can promise you I and many, many others are working diligently to eradicate this mindset, the fact that Barbur (and so many other streets like it) continue to claim victims while we toil is utterly heartbreaking.

“…the fact that Barbur (and so many other streets like it) continue to claim victims…” Brian Davis

Except that Barbur doesn’t claim victims. The road is not dangerous when driven and ridden responsibly. People bring about their own deaths, and occasionally that of other people on this road, through their own bad driving.

Livability of areas near to roads, and functionality of roads for travel by means in addition to motor vehicle, may today, have some chance, in some situations, of holding sway over throughput objectives being the top priority. Whether Barbur is one of those situations that calls sufficiently strongly for a restoration of livability of times past, remains to be seen.

If only there were some other livability increasing road near Barbur that people could use to get to downtown…….

Ride Corbett. Much nicer road to ride. Drop down onto it just east of Terwilliger, so a little travel on Barbur is involved. Enters town a bit east of where Barbur does. Does have some climbing involved.

I meant for cars…….

OAR 734-020-0015 (2a) describes the methodology for conducting speed studies. http://tinyurl.com/OAR734

The methodology states that free-flowing speed is the standard of comparison, combined with a review of crash rate. Think of it as grading on a curve. Absolutes are not part of the equation (No vision zero), but relative safety is the standard. So, if your road is doing better than the average, something else (2b) has to be going on for speeds to get lowered (IMO). Check out section 3.

Neighborhood groups and transportation activists shouldn’t be coming to ODOT hats in hand asking for a road diet. It’s on ODOT to demonstrate why this ridiculous road configuration even exists.

If we were building a brand-new 1.2mi stretch of street parallel to I-5, would ANYONE suggest to put in a four- to six-lane highway? Especially considering this 1.2mi highway would have stoplights and congestion at either end?

I live in Collins View near Market of Choice. I work in Lair Hill. This road serves ME better than almost anyone else on Earth but it’s a rare day when I drive on it instead of I-5.

“…If we were building a brand-new 1.2mi stretch of street parallel to I-5, would ANYONE suggest to put in a four- to six-lane highway? Especially considering this 1.2mi highway would have stoplights and congestion at either end? …” Paul Souders

Barbur is a continuation of highway 99w, given the name Barbur Blvd, at which point along the road, looking at the map, I’m not quite sure. As part of 99w Barbur serves as a highway that runs from Portland, west through Tigard and on to Newberg some 30 miles away from Portland.

Fairly sure that 99w-Barbur as a highway, precedes I-5’s presence through the same general area, by many years. 99w-Barbur’s longer presence and the function it provided then and somewhat continues to, today, likely accounts in no small part, for why the road came to have the multiple lanes in each direction configuration it has.

Making exaggerated claims that deaths of five people driving on this road over the last five years, must be due to some flaw in the road’s design, isn’t likely to make a convincing argument that the road’s number of lanes need a road diet so the bike lanes can continue unbroken over the road’s two bridges north of Burlingame Terwilliger.

Like I’ve said a number of times in past: Put the road diet idea in place as an experimental test for a determined period of time, three months, six months or a year, for example. Give it a fair test. Not a construction zone serving as a stand-in for the diet, but an actual road diet with all that implies. If it doesn’t work out, return the road to its present configuration. After the experimental period is completed, subject to approval, the road diet and its continuous bike lanes over the bridges, stay. If not approved, the road diet and the continuous bike lanes go.

When the “big one” hits Portland, I think this city will have a lot bigger concerns than I-5 or Barbur being passable. Think “Mad Max” levels of lawlessness. Lock and load NOW.

Really? I think Portland is the kind of place that would handle something like that well. Look at the Disaster Relief Trials, the urban farming, the community spirit. Just a hunch but I’d rather be here than say, L.A.

ODOT’s prioritization of traffic over safety subverts Vision Zero and becomes… Zero Vision.

I kinda feel bad for the traffic modelers since they’re merely doing their job of analyzing traffic. Buy hey, since they’re playing around with numbers, maybe it’s time to consider doing the math (just like I did back in 2010 http://seattletransitblog.com/2010/08/25/road-diet-disconnect/#comment-132592) from the safety angle. Please accept my apologies in advance for suggesting that a value should be assigned to someone’s life in the first place.

So then, ADT is 14,500 vehicles (http://bikeportland.org/2013/09/12/metro-traffic-engineer-says-odot-memo-overstated-effects-of-restriping-barbur-93830) giving an AADT (average annual daily traffic) of 5,292,500. Assuming that every single vehicle experiences a delay of 68 seconds (they don’t, that is only for the AM Peak), that is collectively 99,969 hours (11.4 years) of annual delay collectively. Assuming that peoples’ value of time has inflated (4%/year) from $25/hour back when I could reference the last study in my previous blog comment to ~$30/hour, that is collectively $2,923,752 cost to society per year.

According to Portland’s SW Barbur Boulevard High Crash Corridor Safety Plan (https://www.portlandoregon.gov/transportation/article/386469), there were 848 property damage only crashes between 2000-2009 or 84.8 per year. I found that the average auto liability claim for property damage was $3,073 in the year 2012 (http://www.rmiia.org/auto/traffic_safety/Cost_of_crashes.asp). So, that amounts to about $260,590 in property damage/year. Yet that report also notes 7 deaths (0.7/ year), 18 incapacitating injuries (1.8/year) and 437 non-incapacitating injuries (43.7/year). So, if the total annual value of lost life and time from injuries (that could be saved by a road diet) exceeds the delay cost minus the property damage cost ($2,923,752 – $260,590 = $2,663,162), then a road diet would be worth it. Put another way, if once every 4.3 years a road diet would save the life of a 30 year old that would’ve lived to 80 years old, then that alone would make the road diet worth doing from a numbers standpoint (excluding the societal/economic/etc output that that person would’ve contributed to society).

Oops, just noticed that the study was for all of Barbur in the city limits, so the crash stats are not all specific to the study area of the travel delay time quoted.

This is absolutely outrageous and disgusting. The recent rework was very disappointing: one of the northbound ramps up onto the bridge sidewalks has a big drainage grate right at the bottom, throwing you off balance just as you’re trying to thread your way onto that dicey, narrow stretch. So contrary to my hopes, cyclists still more or less forced to share with the general traffic lanes on Barbur.

Now this lame justification is just a spit in the face on top of everything else.

FWIW I’m now living in Minneapolis, but Barbur is still a hot button for me, since I used to commute on it regularly.