Some people, upon hearing cycling and transportation activists talk about new road designs or different infrastructure funding priorities, respond with statements like, “but not everyone can bike” or “some of us need our cars.” What’s lost in these debates is that even a relatively small shift in how we get around, Oregonians — and the state of Oregon itself — could see major positive impacts.

As part of their preparation to build a 2025 transportation funding package, the Oregon Legislature is hosting meetings to educate lawmakers and hear input from experts (I mentioned these workgroups in my previous post about the budget). In a November 20th meeting of one of these workgroups, Miguel Moravec from the Rocky Mountain Institute shared a presentation about how Oregon would benefit from a shift in mode choice.

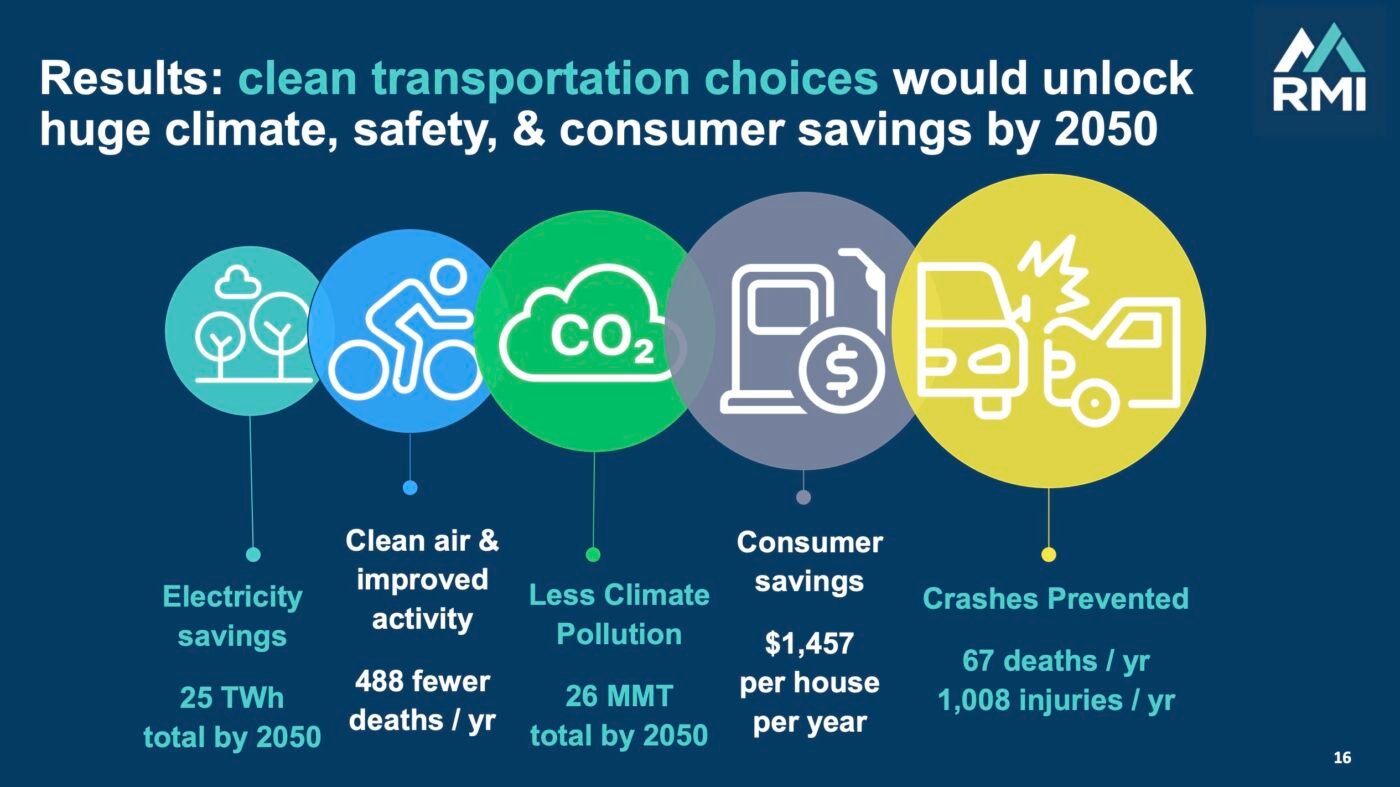

RMI is a nonprofit think tank that started during the oil crisis of the 1970s and now provides research and analysis “to advance the clean energy transition.” You might have heard about their widely-used induced demand calculator tool, which is used by The Street Trust in their candidate training program. Moravec brought a different tool to the legislative working group: something RMI calls their “smarter modes calculator.” Using that calculator across a 2024-2050 timeframe, Moravec based his presentation around what would happen if Oregon was able to shift just 20% of its current driving miles to other modes like walking, cycling, or transit.

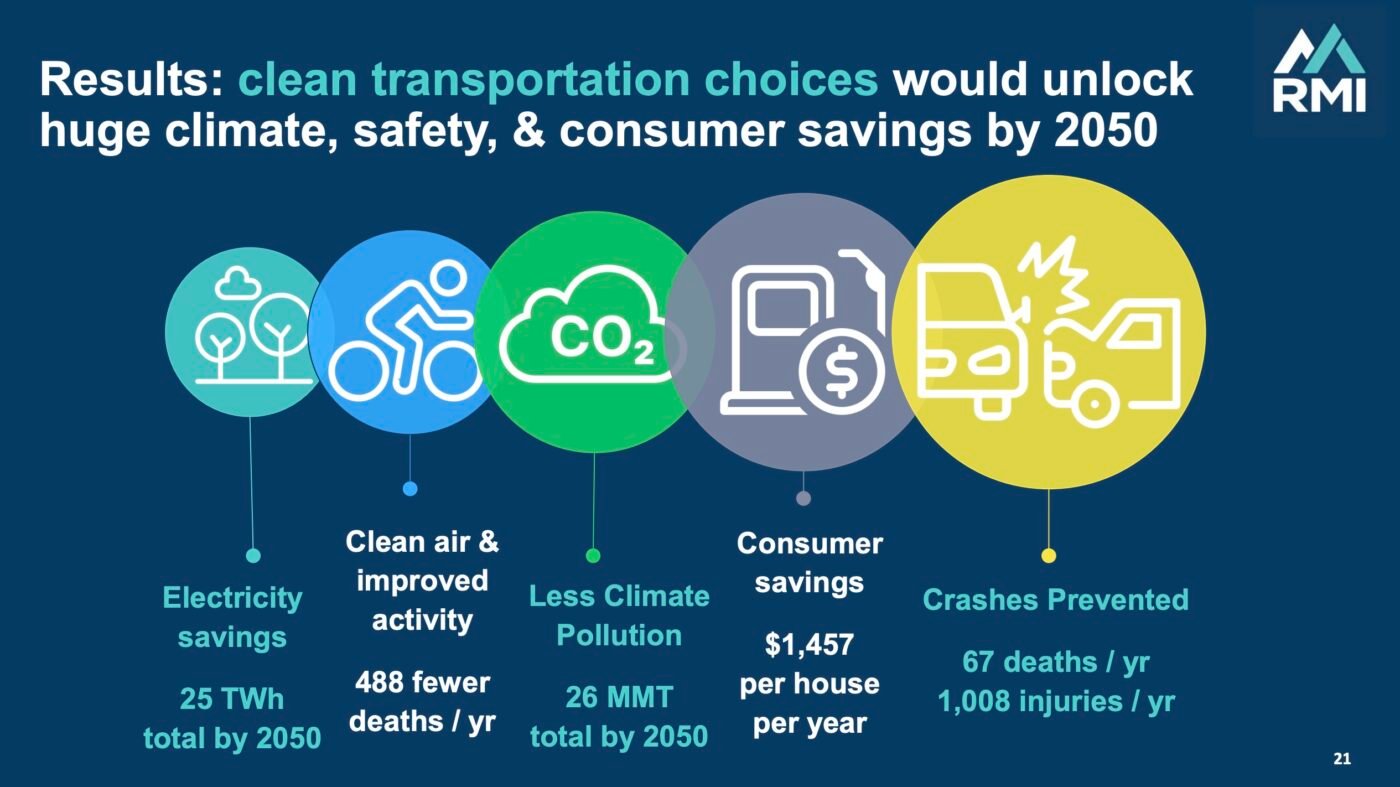

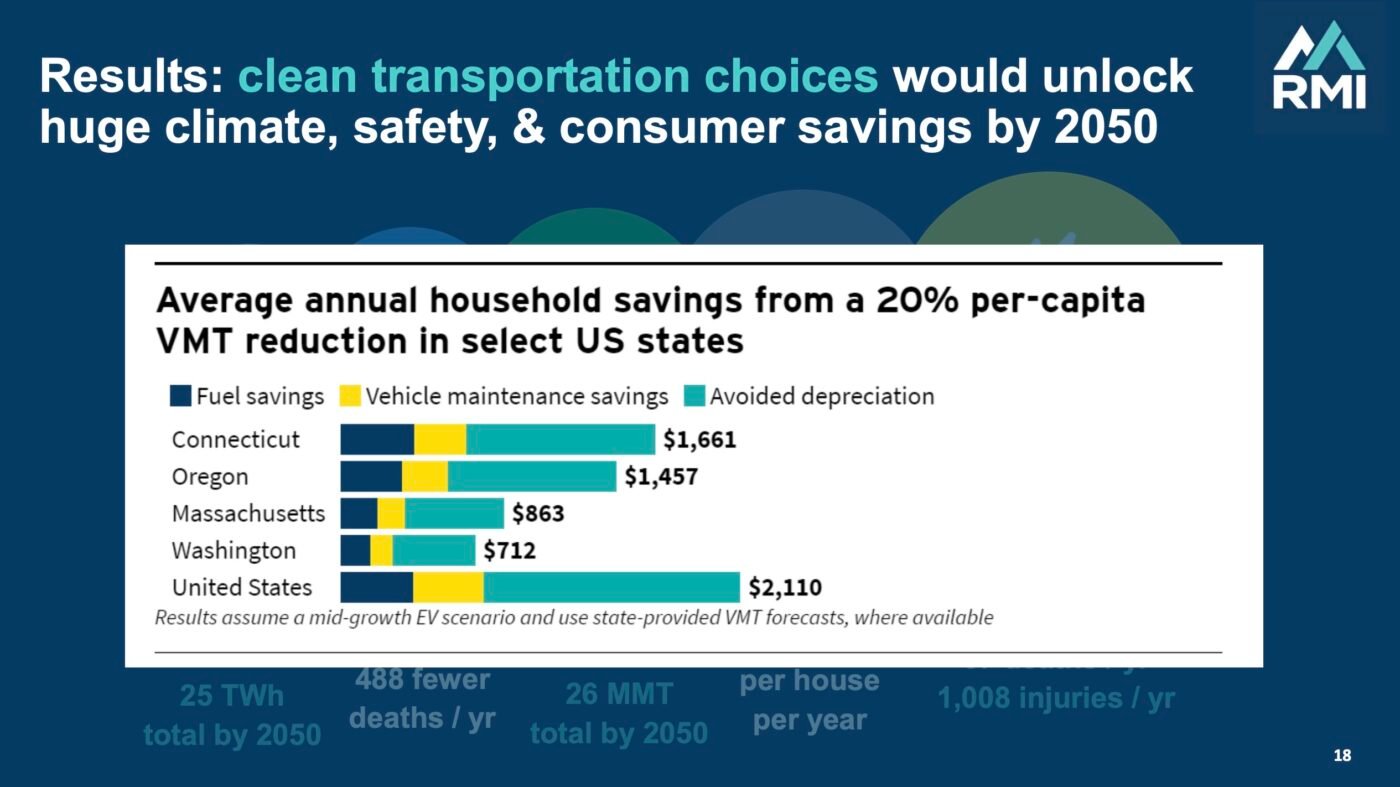

According to Moravec, if Oregon residents shifted just one out of every five auto trips to a non-driving mode, every household would save $1,457. “This is a literal stimulus check-sized boost,” Moravec said. (Or about $500 larger than the size of an average “Oregon kicker” rebate.) RMI’s household savings number is based on the fact that the average cost to own and maintain a car in the U.S. is about $12,000 per year and the average Oregon household owns two cars.

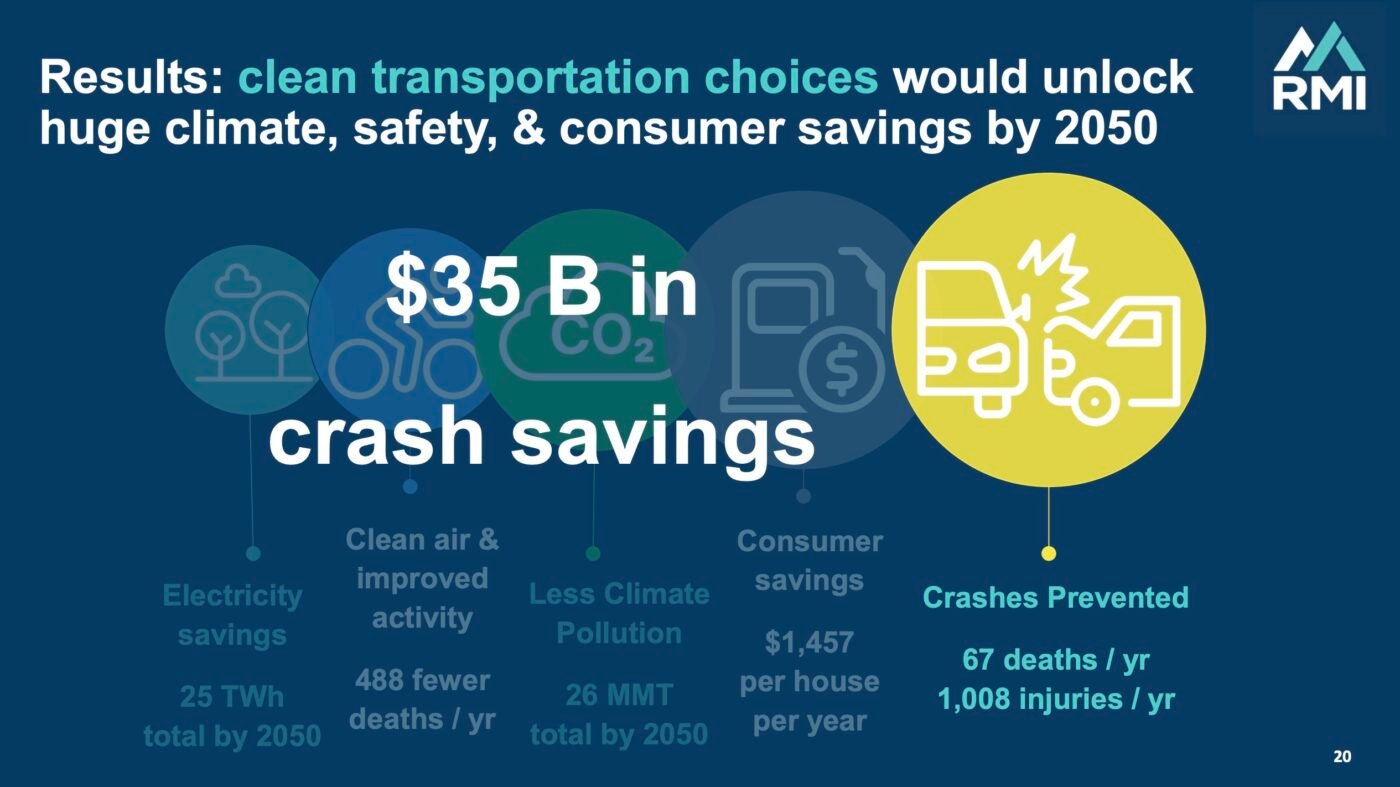

Other benefits of a 20% vehicle miles traveled (VMT) reduction would include: 488 fewer deaths per year due to improved air quality and more physical activity, and a reduction in crashes that would save 67 lives and prevent over 1,000 injuries per year. If that’s not enough to sweeten the deal, a 20% shift would prevent 25 metric tons of CO2 from being released into the atmosphere. There’s a cost to road crashes too, and RMI’s calculator reveals that Oregon would save $35 billion just by putting down their car keys and lowering road exposure time.

There would be other livability and urban planning benefits as well. Moravec used a case study of Arlington, Virginia, to show how when city planners made non-driving modes more attractive, they also boosted the local economy. “Clean transportation choices in Oregon can stimulate Main Street economic activity, and it’s a virtuous cycle because as residents’ need to drive decreased, the area became more desirable to live.” More human-centric places create a stronger tax base for local governments, Moravec shared, a benefit that is amplified when fewer car trips lead to savings on road maintenance costs.

To unlock all these benefits, Moravec said lawmakers cannot just hope people change behaviors on their own. The legislature must support and implement laws and programs that entice fewer car trips. What type of policies do this? His presentation pointed to congestion pricing in New York City, as well as a state payroll tax and casino tax. In New Jersey, lawmakers have passed a tax on corporate incomes to fund transit. Colorado and Minnesota have a fee on home deliveries from the likes of Amazon to fund transportation options, and Minnesota is expected to raise $700 million a year from a combination of regional sales taxes.

Keep in mind this presentation was being heard by a very influential and powerful group of lawmakers, advocacy leaders, and ODOT staff that included: Co-chairs of the Oregon Legislature Joint Committee on Transportation Senator Chris Gorsek and Rep. Susan McLain, Oregon Transportation Commission Chair Julie Brown, and many others.

Rep. McLain expressed interest in the home delivery fee and Rep. Kevin Mannix wanted to know more about the funding package passed in Minnesota.

This was just one of many presentations that has been shared with lawmakers in recent weeks and months. I’ve been impressed with the amount of information and feedback that’s being processed during these workgroup meetings and can’t wait to see what type of proposals end up on the table once the legislative session begins next month.

Thanks for reading.

BikePortland has served this community with independent community journalism since 2005. We rely on subscriptions from readers like you to survive. Your financial support is vital in keeping this valuable resource alive and well.

Please subscribe today to strengthen and expand our work.

This sounds pretty easy; just get people to switch 20% of their miles driven to bikes and transit. Why didn’t anyone think of this before?

I wish someone would think about what it would actually take, specifically, to make this happen, and present a plan along with a realistic estimate of costs.

I hear you Watts. That’s what I hope this is leading too. The folks in this working group are literally right now putting proposals on paper that will create new funding and new priorities for Oregon transportation that will get folks to shift away from cars. Obviously it’s a wait and see, but your call for some action is what is happening right now.

People have been trying to accomplish this in one guise or another for many decades. Funding is not really the problem; a lack of actionable and effective ideas that are politically palatable is the problem.

Not sure I understand what you’re trying to express Watts. I guess I’m curious what you consider, “actionable and effective ideas that are politically palatable.” Are you talking about good projects? Or good revenue streams?

I’m talking about the lack of specific plans that are actually implementable that would reduce VMT by 20% statewide. Finding funding is the easy part; finding ideas that would work in the real world (which includes passing political muster) is what’s hard.

I’m guessing that if someone said “here’s a credible and politically palatable plan that would reduce VMT across the state by 20%, and it would cost $200M per year,” we’d find the money.

OK thanks. I think one thing to keep in mind is pricing pressures. As driving becomes more expensive, people will do it less. That’s a key problem in America. Driving is waaaay to cheap. Anything we do in Oregon in the 2025 session will result in making driving more expensive… and we need leaders who can convince voters that that’s a very good thing! And one result of that price pressure is that a percentage of people will begin to drive less… maybe not 20% less but that’s a nice goal!

That remains to be seen. Any significant increase in the cost of driving will be politically painful for many representatives, especially in suburban and rural areas. Queue the equity concerns.

Indeed, we do. Know any?

with a Dem supermajority, if Oregon fails to deliver a transpo package this session it will be a failure on par with the Dems failure in the national election last month IMO.

I went to an all-day conference in September in which RMI also presented the same ideas but with NC data, and the same questions Watts has, came up – repeatedly – and the same lame answers. Most of the audience were Dems in a state that Republicans have a near supermajority – everyone was confident that Harris would win and magically push our state to a Dems majority – but even then everyone agreed that it is super hard to move 20% of present trips out of cars when well over 70% of state residents have no access to public transit or any sort of safe bike or walk infrastructure.

Even in places you do have good access to such infrastructure, such as in Portland, it is proving quite difficult to meaningfully move the needle.

There are some people who have a strong faith that it is possible, but they have difficulty saying how, exactly, it could be done. I have nothing against religion, of course, but it’s not a good basis for effective policy, especially when most people are non-believers.

Let’s talk about religion. Let’s talk about the religion of machines, of cryptocurrency and “passive income”. Lets talk about people who “believe” that electrification and automation will solve all of the negative externalities of cars. Let’s talk about how the religion of capitalism is very happy to throw up a shield of “equity” and “disability” for any non-preferred policy despite being creators and exploiters of those very things.

The US car-centric transportation system is the most dangerous AND the most expensive option, and the result is massive death and inequity. There are many cities and countries that have made changes, providing evidence that cars are a net negative for society. Despite that, there’s a fervent religious belief that cars are going to somehow make us all wealthy. There’s a fervent religious belief that these giant, hulking machines will be made safe by some altruistic techbros. There’s a fervent belief that our roads and cars are “already built” despite both the infrastructure and the vehicles being a MASSIVE ONGOING COST that we pay every year.

You want some concrete plans, here you go:

Every single one of those plans is more likely than trusting that automation and electrification of multi-thousand pound vehicles will *someday* be safe and efficient and cheap.

If you really want to see what a cybertruck/cryptofascist future looks like, I recommend moving to Austin Texas, the place I just left. You can stand outside the whole foods and be in awe of the multiple 12-lane intersections. You can go to the center of downtown and marvel at the 22-lane highway expansion that’s under construction. You’ve got choices for work: you can either be a tech worker who can afford to live in the city (if you can find a job) or you can be a food service professional who lives in the exurbs and commutes 40 minutes each way. Your pick.

I didn’t write this for you, by the way. I wrote it for the people who come in here and read the crap that trolls put out. See, the goal of trolling is to bring down the audience, to move them to a place of depression and inaction. Maybe my words will help provide some hope after your condescension.

Sure — I don’t believe in any of the things you listed (except passive income, which anyone with a bank account or 401k plan knows is real), but some of them, at least, might make interesting topics for conversation.

You made three specific proposals. I am skeptical they’re realistic, or would meaningfully move the needle on VMT, but if there were sufficient political support to implement any or all of them, I’d be in favor. Contact your elected officials and tell them your ideas.

In terms of what I actually do believe, I think automation is coming (I can try it today in one of several US cities, and many more abroad). What we do with that is up to us, but pretending it’s not real is probably not going to be the most effective response. I think systemic change creates opportunities, and it’s up to us how to exploit those to build a better city.

I agree with Watts…”Queue the equity concerns”. “Equity” will prevent the Democratic supermajority from doing anything of consequence regarding shifting transportation mode.

I’m surprised you think a Dem supermajority will be a force for good on transpo issues when all history suggests otherwise. It’s been dems who are pushing the IBR freeway expansion boondoggle, the Rose quarter freeway expansion, the dems who have controlled the purse strings of Portland for decades and yet active transportation is worse as well as making public transportation worse, dems who allow/suggest ODOT operate on a bond mentality saddling future generations with increasing debt and inability to use funds for actual transportation. If I’m not mistaken it was dems like Schrunk and Goldschmidt plus supportive council members and local union support that put I5 and Emmanuel Hospital through the Albina neighborhood.

Maybe thinking belonging to a certain political party makes one a good, moral person eager to help solve the issues of the day is not how the problems are going to be solved when it is one particular party (in Oregon) over the last several decades that have been firmly on the wrong side of improved transportation issues for anything but cars.

Given how Dems in the past have acted on transportation I would be terrified if they were able to pass a comprehensive transportation bill as going on history it will be wildly biased towards cars and/or lining the pockets of their political supporters to the detriment of the population. .

Because I never said that! I just said they should be able to pass something. I’m well aware that it’s Dems behind massive freeway projects and that bad transpo policy can come from any party!

Please try not to assume my beliefs and read what I write carefully. Thanks.

This is what you wrote. Why would you want them to pass something if you don’t think it is a good thing? it seems you want them to pass something otherwise you would not use the term “failure” to describe not passing some kind of legislation. Do you want them to pass a bad package?

I would hope not. I assumed you think it would be a good thing and a net positive for transportation if they passed a package because i thought you would not want a random or detrimental package passed and that anything passed should be good for Portland and Oregon. Maybe I was wrong. It’s happened before.

Wow ok so it happens so often and I’m tired of having to defend myself like this… But it feels to me like you and some others on here will often read into what I type and ascertain some type of opinion or bias or belief when in fact what I am doing is just sharing information and often information that is not expressing some feeling or opinion. Does that make sense? In this case I typed a statement that I feel like Dems should be able to pass something and if they can’t it will be a failure. One person thought that meant I support whatever Dems pass and you are assuming I think whatever they pass will be good. I never said any of that.

I’m making a punditry-type statement, saying that it would be a political failure to not pass a necessary revenue package with a one-party super majority. I wasn’t making any value judgment about what they pass whatsoever.

Obviously I want them to pass something that I like! I just want folks to give my words fair treatment and stop implying my motives that aren’t there. Thanks.

It’s ‘cue’ not ‘queue’. But you’re on the money about the political appetite for raising the (marginal) cost of driving. I think the best strategy is to divide the automobile supporters by pitching arguments to rural folks to the effect that ‘their’ taxes are funding urban roads and should be supplemented by tolls that only people who drive in the city pay.

“It’s ‘cue’ not ‘queue’. ”

No — we’re talking about Oregon Democrats… I was thinking there would be a cripplingly long line of equity concerns, queued up around the block.

If you want to cut statewide VMT by 20%, you’re not going to get there by tolling only relatively short intra-Portland trips, if there were even a way to do that. Rural trips are going to have to change mode too, and I have yet to hear anyone pitch a compelling system of rural mass transit that could compete with taking the F250 on a bi-weekly Costco run.

Agreed. I don’t think 20% VMT reduction is realistic. That’s not a reason to avoid making improvements, and I think tolling is something to consider. One reason I think so is that a competent politician could conceivably gather enough support for it. Of course government competency is in short supply….

I’d support tolling, so long as it didn’t divert vehicles off highways and arteries onto the streets I walk and bike on. I would also oppose proposals that involve tracking where individuals drive, something I think a solid majority of Oregonians would agree with me on.

But sure, bring on the tolling (especially after we see how the system performs in NYC).

Driving is way too cheap. But the real killer is that only a fraction substantially less than one of the (significant) cost of driving is reduced by changing trips to bike/transit. To do many things one ‘needs’ a car and hence spends a lot of $$ before the first mile is driven. It’s like a ski pass — once you’ve paid for it, you might as well use it. I own a car, and it would be quite inconvenient for me to go without it. Given that the car is available, it’s the cheapest (not to mention the most convenient/fastest/most comfortable) mode available to me.

So why don’t you like (marginally) cheap/convenient/fast/comfortable? Let’s figure out how to reduce the external costs, and maybe accept that in many cases, for many people, automobiles are a pretty good choice.

Because the total cost (to me and externally) is high. Socially, automobiles are a terrible choice — I don’t enjoy or want to drive, but I haven’t found a better alternative for long trips. Personal transportation choices are clearly conditioned on our built environment. A good road network (necessary for the current auto dependence) is artificial: it is the product of organized political action. The ‘pretty good choice’ that many people make has been encouraged by government policy. If we had (historically had) better policy people would make better choices now.

This may well be true, but it doesn’t change where we are now. We’ve got what we’ve got, and we need to build from that. For better or worse, that gives motorized road vehicles a huge advantage because the necessary infrastructure already exists.

I’m the first to admit there are large downsides to having a society built on driving. But there are some pretty big upsides as well (some of which you identified), and replacing driving with some other transportation mode that does not offer similar (or compensating) upsides is going to be hard. This is one reason convincing people to use transit is so difficult.

So I, at least, am heartened by ongoing efforts towards electrification and the promise of automation, which, between them, could address most of the negative aspects of our current system of driving.

I’m happy to have people exploring other ideas, but the world is changing, rapidly, and most of the alternatives people propose do not reflect this. Rather than debating, yet again, whether transit can get a little more mode share if we just spend more money, or if a marketing plan from PBOT can convince a few more people to ride bikes, we should be thinking about how to shape the coming world so it’s more to our liking.

Not sure I understand where you’re coming from. I’m also not sure the world is changing that rapidly in ways that are meaningful to transportation infrastructure projects. TBH, this seems like a time of stagnation for the road system. Even the mega-projects like IBR or the RQ only make incremental changes. In a future where we are being terrorized by electric, autonomous muskmobiles instead of ICE SUVs I will still want transit and biking to be designed and built for. And I will still want tolling to produce a revenue stream for it.

That’s exactly what I was doing when I suggested tolling. But that was just one off the cuff suggestion that has been shown to be feasible and successful in many places. I would also like a good light rail system with frequent service over an extensive network like exists in many cities … but tolling seems like an easier political lift that moves us in the correct direction. What ideas do you have?

Sure. It would be nice. I’m not sure Portland is up to the task, or would even support such a system. We voted down the last proposal to build new rail infrastructure (back when Max was still generally well regarded, unlike now). Maybe next time?

With a reduced focus on downtown, does new LRT even make sense? It costs $10.69[1] to provide a single passenger a ride on Max, and costs are climbing. That’s not sustainable (though still better than WES, which costs almost $100 to serve a single passenger!)

Do people want to bike more? Apparently not, or they’d be doing it.

We agree the current situation is stagnant. I really don’t see many good options for moving the needle given today’s landscape; we’ve tried lots of things, and here we are. RMI (the subject of this article) wants to reduce VMT by 20%, but, despite focusing on the issue, has not proposed any specific ideas about how to accomplish it. No one has a plan.

Electrification and automation are potentially huge, transformative, once-in-a-lifetime changes, and could help resolve many (but not all) of the intractable transportation issues we currently face. With automation, for example, ubiquitous tolling (if that’s still desirable) becomes as easy as raising the tax on beer (ok, not easy, but a standard policy fight, unlike today).

Whether you like them or not, these things are coming (and will likely be upon us well before we can get even one more LRT line in service). Whether we use them to build the city we want or simply react is up to us.

[1] https://trimet.org/about/pdf/2024/Apr%202024%20MPR.pdf

Since you raised this again, I have to ask: what connection do you see between automation and tolling? There are toll roads on the east coast, CA, etc. all tolling human piloted cars. It’s not hard — just build a little hut and pay a dude to sit in there and collect the toll from each car. If somebody refuses to pay, send them a ticket or whatever. The Bridge of the Gods is tolled, FFS. Maybe the one at Hood River, too?? Seattle tolls 520 now, I think. I can see how robot cars could make it easier to do the bookeeping/venmo, but that’s a problem that’s been solved for at least a millennium. Today, given appropriate legislation, we could start soaking people crossing the Columbia by personal auto — no technological revolution required.

This is another thing you’ve mentioned a couple times, which has piqued my curiosity. What positive changes could we bring about during this period of rapid change if we really grab the bull by the horns? Like RMI, you point out that things could be better but don’t give a plan to get there. I think there is a bigger issue that there is not a consensus/vision of what we even want to achieve, but I’d be interested in the broad outlines of what you would like to see.

I am fairly confident that automated vehicles will be primarily appear in the form of taxis. The owners will know where they are at all times, so assessing a toll on them will be easy, a bit like tolling TriMet busses.

Tolling human drivers is harder; you have basically two choices: 1) only toll specific controlled access roads (with the impact of driving traffic off of them onto local surface streets); or 2) track where everyone drives and toll them accordingly, with possible diversionary effects if you toll different roads at different rates. (And no one builds human collected tolls anymore; everything new is automated.)

Certain geographies let you do option 1 without much diversion (such as tolling the Columbia River bridges), but most other places in Portland will create problems for other facilities. Toll I-205, for example, and 82nd will take a big hit.

And yes, I agree, we could toll the Columbia bridges today with no new tech and no diversion (and I would support doing so). But that would be a pretty limited tolling program, and might not even be legal under federal law regulating tolling at state lines.

Things we could do now are set up a legal framework to ensure that when automated cars arrive here, we have data sharing requirements, rules preventing using neighborhood streets as cut-throughs, designating areas for parking/no-parking of automated vehicles, etc. Develop a fee structure for AVs to ensure we get revenue from them. We should also be developing a system to allow renters to charge EVs at home, regulations ensuring fire safety for EV storage in apartment buildings (applied to motorized bikes as well), etc.

The video linked elsewhere projected that automation companies will push for pedestrian hostile road changes that make things better for automated vehicles. We should strengthen community participation for any traffic/street modifications to provide a bulwark against automated vehicle companies running roughshod over city planners, as AirBnb and Uber did when they arrived in town. (I know, people here just hate community involvement.)

As for a plan to make electrification/automation happen? Unlike RMI, I don’t need one, because electrification and automation will arrive regardless (our choice is how prepared we are), while reducing VMT by 20% is absolutely not going to happen without a good plan. In this regard, the two concepts are asymmetrical.

Thanks for the reply. So you think it’s easier to track/toll autonomous vehicles than piloted ones because the robot does not yet have privacy rights? For sure we need to extract money from any robot taxi service. I think uber and airbnb are great examples of what to avoid. I’m skeptical that a large fraction of current VMT will be displaced by AV in the near/middle term (and even more skeptical that this is desirable), but I could be wrong.

No — I think they’re easier to track because they’ll be fleet vehicles, and fleet owners usually track where their vehicles are. From ODOT’s standpoint, it will pretty much be a matter of setting a rate and getting the companies to pay, just like, say, the alcohol tax.

A lot hinges on safety. If AVs have a sufficiently established safety record, I suspect there will be financial and other pressures to speed up adoption (think insurance companies and worried parents, for example).

If AVs do not prove safer than human drivers (a low, low bar), the whole project will likely fail.

Early safety data is quite positive, and it seems very likely to continue to improve, but it will be some time before we can be fully confident one way or the other.

Ultimately, it’s hard to make predictions, especially about the future. EV adoption seems a near certainty, AVs less so.

OK, so it’s being part of a fleet that makes it easy to toll? Maybe (by which I mean surely) we should be charging the current uber/lyft trips. Amazon/brown santa, too. I’m still not seeing how the humanity of the driver is connected to the feasibility of tolling/taxing them. If what you’re suggesting is that we should tax autos more and that E/AV adoption represents a political opportunity to do so, I’m on board. Send me a sample letter, and I will blow up my legislators’ and council members’ inboxes/voicemails. If we try to charge commercial fleets, they will scream about how unfair it is that they are singled out and treated differently. And I don’t see AV taxis meaningfully displacing the personal auto (how is a robot better than an immigrant who will work for low wages??), so I don’t see how tax fairness arguments are strongly affected by making the driver less human.

“Maybe (by which I mean surely) we should be charging the current uber/lyft trips.”

I don’t know whether we should or not, but we certainly could assess Uber, Amazon, and other fleet vehicles a per mile tax much more easily than we could private drivers. You are right that it would be a big political fight, but that’s nothing new.

If AVs win out over human driven taxis it will be on the basis of price. If they are not both cheaper and safer, they’re not going to work.

I haven’t given a lot of thought to what sort of tax regime would make sense in the context of automated vehicles. We may want to tax them, or maybe not. After all, we highly subsidize public transit, and it is possible we might want to subsidize at least some AV trips as well. I just don’t know. What I do know is that we should be thinking about it.

You’re thinking about it the wrong way. There’s really nothing stopping anyone from biking to the store right now.

The problem is that we have made driving a car so darned easy, convenient, comfortable, and safe that no one wants to do anything but drive a car. Cycling simply can’t compete with these aspects of driving a car, so we need something else, like a gov’t mandate to drive less, Maybe *that* is what Watts is referring to?

The irony is that we need almost NOTHING to improve mode share, except for the will of The People to make it happen.

You’re right! And yet, for some reason, people aren’t doing this en masse. As you say, people like their other choices better (even riding transit).

Again, absolutely true! Anyone who wants change can have it, today. What’s harder is imposing that change on others who don’t want it.

PS What would a “mandate to drive less” look like, and how would we make it politically salable in Oregon?

Maybe something like the Covid lockdowns? Declare a public emergency, on Wednesday everyone who has an odd-numbered license plate will be banned from driving, with $1,457 minimum penalties, on Thursday the even-numbered plates will be banned? When Paris has air pollution emergencies I hear they do something similar.

“My job interview is on Wednesday! The nearest Tri-Met stop is over a mile away from the interview and it’s pouring outside. I guess I won’t get that job because my plate number ends with a 9.”

“My child is vomiting and has a high fever. The school needs me to pick her up immediately and…CRAP! It’s Thursday and my husband has the car with the even plate! How do I order an Uber with an even number plate?”

“I love driving anywhere I want, whenever I want! The cops can’t ticket me because my vanity plate reads BLZR FAN. No numbers = no restrictions!”

I have no idea what this means. There are methods based on research that increase mode share consistently across many cities and countries around the globe. The will of the people is not an operational definition, i.e., we cannot operationalize and measure its effect on mode share.

This statement shows a lack of empathy for why most people don’t choose to use a bike for everyday use. We have solid evidence regarding the “interested but concerned.” We know why they do not choose to bike, and we have solid evidence that tends to increase their bike usage.

We know why they say they don’t bike, and we have recent, Portland-specific evidence that building bike infrastructure does not increase bike usage here.

Look for that research and show me the evidence.

Bike lanes up, bike riders down. I think these are generally accepted facts; do you really need a citation to believe them?

Look for the evidence to support your hypothesis and show me the research.

If I believed you were making a good faith request for information, I would help you find a source or modify my claims to not rely on the disputed assertion.

But that’s not the case here. You are being argumentative to distract from the fact that what you call “solid evidence” (i.e. stated preference survey data based on hypotheticals and conversations with people at Sunday Parkways) is confounded by contradicting historical trends.

I don’t claim that building more bike infrastructure cannot increase ridership in Portland, but I do claim that there is no evidence it will as long as whatever has been suppressing ridership is unaddressed. I do not know what that thing is, nor, apparently, does anyone else. But we do know it is probably not a shortage of infrastructure.

I am strongly in favor of building more stuff for bikes — I ride a lot and I like good infrastructure as much as anyone else (and it’s especially nice when I’m the only one using it), and I would love it if PBOT would spend more money catering to me. I wish building more were the key to reviving Portland’s bike mojo (to use a word from better times), but there is no evidence it is. We keep building, and ridership falls.

That is the basic argument you don’t want to engage with. I am willing to accept that, in a vacuum, more infrastructure will lead to more bike riders, but we are not in a vacuum, and your “solid evidence” isn’t a prescription for increasing ridership in Portland.

You probably don’t actually care what I think (I’m just some internet rando who thinks cars can drive themselves), but anyone holding the purse strings is going to be asking the same questions I am (Roger Geller and Steve Novick have done much the same in recent weeks), so figuring out how to answer them (or restructure your arguments to avoid them) is an exercise with value well outside the realm of BikePortland.

I’m open to a good faith discussion with you on this topic, or we can move on.

I know what it looks like: I don’t use my car for ANY in-town trips that I can bike to. So my mode share is something like 80% bike, 20% car.

If we could get half of people to do just their in-town trips by bike, we’d shift mode-share radically.

Easy! Grow our urban bike mode share from 3% to 50%. Sounds totally doable.

(Also, it’s not the number of trips, but the miles traveled (the MT in VMT), so one long trip across the state could easily blow your percentages if most of your city trips are short).

In sum, by arguing that nothing will change, positions will always be supported by established superficial observations, will not contribute anything creative and therefore will assume the least possible risk.

I never said nothing will change; I think everything will change. I just don’t think anyone has a plausible plan for reducing VMT by 20% statewide, and that systemic change will not come via efforts like this.

I would love to be proven wrong.

Awesome.”Everything will change.” Another factually correct statement. This is as valuable and imaginative as the solutions that you propose.

Unlike the statement “we can reduce statewide VMT by 20%… somehow”.

SD, Watts is here to express his primarily rationalist opinion without having any real interest in understanding empiricism (evidence that suggests things that undermine or support those opinions). Unfortunately, I have found engaging with him most often fruitless and sometimes find his ideas bland sophistry.

Winning arguments through exhaustion shouldn’t be the point of comments. My hope is that we all come on here to be helpful in educating and engaging with people by sharing different ideas in order to improve our environment, not merely here for ego tripping based on likes or gotchas.

In this case, we are taking about the possibility of something extraordinary — reducing statewide VMT by 20%, without anyone able to explain how it could be done.

I am highly motivated by evidence and reasoning, but, in this case, there is none to discuss.

I too want to improve our environment, but we can only get there by dealing with facts rationally and understanding the consequences of various options.

Reducing VMT would be great, but only if someone can figure out how it could actually work.

And instead of maintaining a stance purely based on opinion and rational argument, you could potentially look at research to support any hypotheses you have with empirical evidence.

Unfortunately, I rarely see you attempt to do this. Rather, you rely on a basic supposition that the status quo is most likely, which is a bland truism and unhelpful. I would encourage you to listen more to people and offer your opinion less. Opinions are a dime a dozen. Evidence to support an idea on the other hand is a difficult and more robust means to support an idea, and often leads to more substantive, nuanced, and helpful content. Arguing that change is implausible is as meaningless as arguing that change is possible. They are simply just platitudes devoid of context. I hope you understand that a lot of people find it frustrating that disregarding evidence by using anecdote is frequently unhelpful for people on this site who genuinely want to get more informed, and not simply wish to voice a strong opinion.

I don’t want you to think this is an ad hominem. I simply hope that you recognize a lot of your comments are unhelpful due to the lack of evidence and reliance on anecdote and strongly held opinion. Thanks for reading.

The reason the status quo is what it is is because we’ve made thousands of decisions that seemed reasonable in the moment that have led us here. And while there might not be anything inevitable about it, it does have to be the starting point for any plan for change. We have to accept that it, and not some other set of facts, is our reality, and that reality closes out some set of possible futures.

I am highly data motivated, and I frequently cite evidence to support my comments, including links to specific sources. In this case, what evidence could I cite to demonstrate that no one has a plan for reducing VMT statewide by 20%? I don’t believe it’s possible, but I can’t prove it, and if someone had a plausible plan, I’d change my view.

(I agree that my “everything will change” statement was a bit of a platitude, but you have to read it in the context of the accusation that I think “nothing will change” when I’ve said repeatedly that I think we’re on the cusp of a once-in-a-century transformation that could give us a way out of many intractable aspects of the status quo.)

Portland and Arlington, VA/Washington D.C. are entirely different animals. Arlington benefits by being a compact city with well-planed commercial centers, frequent transit, expanded transit hours, and a significant amount of transit overlap with Metro. Whenever I go there, I never rent a car because I can get anywhere with relative ease on mass transit that is easily demonstrated as more efficient and less expensive than car driving. Final mile or getting to a further flung residential zone in poor weather – Uber/Lyft for a few bucks. Most importantly, there is visible security and you can’t get to a train or on a bus without proof of payment. If I lived in that area, I wouldn’t own a vehicle because the system is that good!

We’ve got…Tri-Met.

Our fundamental issue is that our transit is not particularly convenient nor is rider comfort/safety a given. There is little commerce along the MAX lines and what is there is plagued with crime, encampments, and feels unsafe. The virtually empty Lloyd Center area is a perfect example of what’s wrong. You can hector people all you like about the environment. You can promote less pedestrian deaths. You can call it, “The right thing to do!”. None of that matters if people feel unsafe or a car trip is faster, more comfortable, and perceived to be safer than riding transit, walking, or hopping on your bike.

To get a 20% reduction in car trips, then you have to make the alternatives far more attractive. That goes beyond any broad funding plans, tolls, congestion pricing, etc. People will use alternatives but the alternative better be very good.

The DC Metro also has no dedicated funding, and Arlington County contributes just 6.7% of the net operating budget of the system (page 14). Meanwhile, DC contributes 36% of the operating budget – 5x that of Arlington – despite having just 2.75x the population. I bring this up most to say that the DC Metro faces huge issues too, you just aren’t likely to hear about them. TriMet, for all its problems, benefits immensely from a strong amount of financial/institutional support from the city, region, and state (in the scheme of American transit systems anyways).

And yes, there are issues with TriMet. The MAX is too slow for most non-downtown trips, especially for people who live in Portland itself. But on some corridors, it’s extremely well utilized – especially Goose Hollow to Beaverton and on to Hillsboro. It’s a central commercial/residential core of most of the western Washington County suburbs, and it gets (relatively) good ridership out there as a result. When the system was planned (and for most of its existence) the Lloyd Center was a categorically different place too. I hardly think that serving a mall + major employment district that has now seen better days is indicative of a poorly planned system.

Now yes, I could think of dozens of examples of poorly planned parts of the MAX system (most of the Orange Line, the 2009 addition of light rail, cars, and parking to the transit mall, the continued existence of downtown street running, the fact that we just spent a cool hundred mil on a Better Red and it’s still just as crushingly slow to get from the airport to downtown as ever, the use of a 120 year old sub-sub-leased bridge as the critical point of the entire system, generally poor land use especially on the eastern leg towards Gresham and along the Orange Line, really awful nighttime service the list goes on), but most of the issues are fixable. It remains to be seen if they will be fixed, but we are in a stronger position than almost any region in the country to fix them at least.

The issue with Trimet as not being competitive for suburban trips is ironic, because the system was designed as a hybrid S-Bahn style / streetcar system, to provide higher speeds in the suburbs and a streetcar like experience in the central city.

Unfortunately, the central city right of way provides a glacially slow transit experience, compounded by the short blocks, stations being too close together, and the Steel Bridge.

The fact that the City of Portland and suburbs are extremely low density, and most of the retail in the city is built around strip malls and car-dominated shopping centers has only compounded the effort.

Basically, Metro has completely failed at guiding dense transit oriented development. Sad, really.

And TriMet built the Orange Line such that it would be difficult to build housing along it anywhere between Powell and McLoughlin. At least they ensured they had plenty of parking at their bus depot.

Yes, but the thing about the stadtbahns that the MAX allegedly draws inspiration from (like Stuttgart) is that they almost always have full grade separation in the downtown cores. When the MAX was being planned, German stadtbahns were planning what essentially amounted to streetcar tunnels for (what an American would identify as) legacy streetcars. There was never strong justification for significant downtown street running.

I feel like this is just factually not true, especially not in the context of US cities. NW, the Pearl, and the major N/NE/SE corridors (Hawthorne, Belmont, Division, Mississippi, Williams, Alberta, etc.) are very obviously not “strip malls and car-dominated shopping centers”. You may feel that they are for rich yuppies (fair), but to say they are “car-dominated” feels like a stretch.

In terms of density, Portland as a city is relatively low density. But you should always take density with a grain of salt. Within the city limits of Portland there is a large international airport, one of the largest urban parks in the country, and a fairly significant amount of industrial activity. Berkeley is well over twice as dense as Portland, but its city limits include far less of the regional industry, almost none of the regional parks, and no airports. Portland also annexed a significant amount of formerly unincorporated land. Saying the City of Portland is “low density” doesn’t mean much when parts of Portland are dense by any standard, it has ultimately arbitrary city limits, and there is huge variation within it.

I bet the money-saving stats would be similar if people just swapped their large SUVs and pickups for smaller commuter cars.

I recently took the MAX from Beaverton to NE Portland, instead of driving. It took a little over an hour, which is ~20-30 minutes more than driving. It was nice to just sit on the train and read, and I didn’t have any issues on board. If the MAX was reliably clean and safe, I think more people would get on board, myself included. I used to work downtown, and could bike or MAX in a similar amount of time. After a few too many “experiences” on the MAX downtown, I wasn’t too keen on riding it if I didn’t have to. I just noticed that Trimet is installing big red security phones at stations. More of those types of proactive safety improvements would help a lot with peoples’ perceptions of transit.

Since I don’t ride Max anymore I haven’t seen those phones. My first question, would be, at 5:30 AM when I’d ride Max (if I wasn’t taking the bus) who would I connect with? I bet no one. Pre-Covid I rode the Max much more, and I never once saw a security person at that time of morning. Never ever. On the ride home, yes, many times.

Now what is TriMet doing about safety for the bus riders? Every week I see multiple occurrences of people boarding the bus and not paying. Most of the time they do nothing, but there are times (at least once a week) where they do act out in what some would perceive as frightening ways.

TriMet’s management has had their day in the sun and have failed. Time to get new management.

I know you don’t have the answers, but your comment made me wonder . . . .

In your caption for this article, i especially appreciated your “maybe don’t take the trip at all!” It’s often overlooked as an option.

People are too often caught on in self-congratulation for taking (or advocating for) non-car transportation for unnecessary trips. It’s not walking or biking instead of driving that I’m thinking of, but more to things like people advocating for bullet trains to Seattle so they can attend a Mariners game.

I would push back against the idea that a trip to Seattle for an M’s game isn’t necessary. Maybe you don’t view someone going to a baseball game as “necessary”, but I certainly know people who would strongly disagree. Sports are an integral part of our society, and its hardly fair to call participation in viewing them as somehow unnecessary.

When I go to see a show at the Clinton Street Theater, am I taking a necessary or unnecessary trip? I’m not fulfilling some basic need, but I enjoy watching weird movies on the big screen. And I think that the local theater scene contributes deeply to what makes Portland, Portland. I wouldn’t insist on anyone calling that a necessary trip, but when I consider moving to a different city the lack of good small cinemas is an actual reason why I find it hard to imagine leaving this place. I realize this probably isn’t the point you’re making, but culture and participation in culture is not some unnecessary part of life – it’s the vital thing that makes life interesting.

And for my money, I think improving rail service to Seattle is a worthy investment. But I religiously ride Amtrak Cascades already, so take that with a grain of salt. People ride intercity trains for all sorts of reasons, but it’s not just a bunch of yuppies riding for unnecessary, frivolous fun. It’s people visiting family, or friends, or loved ones and a whole lot more.

Questioning spending billions so someone can take a faster train from Portland to a Mariners game is nowhere close to saying participation in viewing sports is unnecessary.

First, I didn’t say going to a baseball game wasn’t necessary, I criticized people who are self-congratulatory about advocating for a (hugely expensive) bullet train so they can attend a Mariners game. You can still attend without a bullet train. I also realize there are other purposes of a bullet train.

Second, you can also find people who think it’s necessary to drive at double the speed limit, drive drunk, park within a block of their destination, drive a quarter mile to the store, park in bike lanes, have a 10,000 sf vacation house, drive a Hummer to the golf course, etc.

It doesn’t matter to me, because you’re not congratulating yourself for being green and responsible for advocating for spending billions of dollars of public money so you can attend more conveniently, or so you can attend a different theater in Seattle.

so what I’ve gathered here is that we should build a bullet train from blumdrew’s house to the clinton st theater

Excellent point Blum. What are considered “necessary” and “unnecessary” trips are often conflated with cars being necessary regardless of their start/end point and other modes as generally flexible in this category. These categories are largely cultural.

Necessary trips depend on context, time, function and many qualitative (not just quantitative) variables that cannot be pared out easily. Is my car trip to the PT necessary but stopping and walking to a restaurant along the way unnecessary? These are circular arguments that are based on a system of design that has been centered around SOV flow and capacity at its base assumptions, with design qualities that work well as roads (e.g., highways outside of a city), but have virtually no application for a city environment.

Those assumptions do not get to the point of transportation system which is intrinsically tied to a quality of life and also a basic quantitative variable: “how efficient can we move the most people in a comfortable and functional means.”

Portland (council, its inhabitants, and PBOT in particular) has not faced this basic principle in any meaningful way. The starting point for any street evaluation for PBOT is measuring the SOV car capacity and speed regardless of what the theoretical function of that street is. That basic concept is at odds with what our city actually needs to create quality and livable space.

In reality there are very few “necessary” and “unnecessary” trips. I would argue that an ambulance is necessary sometimes, but that does not necessitate widening roads or the absence of separated bike lanes. Ambulances actually move much faster (and safer) when using separated space whether it be pedestrianizing a street or allowing emergency vehicles to use the PBL during emergencies.

Delivery vehicles could be considered necessary but again widening roads isn’t a realistic solution because it simply just adds cars/congestion. In NYC the sheer amount of delivery vehicles has necessitated logistical hubs (and ebike gathering areas) where cargo bikes are much more efficient at navigating city space for relatively shorter distances. Again, delivery vehicles and cargo bikes move much more efficiently on pedestrianized streets.

The argument for widening highways for freight is also somewhat bizarre since widening a highway simply induces more SOVs. Freight can be considered “necessary” but there are other ways of dealing with this more effectively (e.g., having delivery times for grocery stores at non peak hours, or having freight only lanes.)

The point I am trying to make is that “necessary” and “unnecessary” are almost entirely cultural definitions, not intrinsically tied to any one mode, function or end goal. We prioritize SOVs in our transportation systems and that makes cars by simple definition implicitly “necessary.” Does a pedestrianized street make every person walking on that street “necessary?”

Anecdotally I dearly miss riding the MTA mostly because of the same families and weirdos I would see on a daily basis. I was going to work, but I wouldn’t trade a swift and magically congestion free car ride to work for any of that. Ultimately, that is a cultural decision on what options we want to give people to interact. Right now in Portland we generally maintain and dump the vast majority of our resources into one option: SOVs. So they become necessary.

I think a more constructive way to think about it is if I deem the trip worth making, it is “necessary,” and no one has a right to second-guess that decision. So your trip to the restaruant is as necessary as the one to PT.

And yet the city requires employees that worked from home during COVID to come into the office at least half the time . They also are encouraging businesses to do the same. And the new mayor wants all city employees in the office every day. How can we make a serious reduction in trips when our city government is encouraging and in many cases mandating unnecessary trips.

There’s a lot we lose when people stay home all day working alone at the kitchen table.

And sometimes a lot to gain.

Yes, lots of people (like your City government example) like the concept of not taking unnecessary trips, but think whatever trips they’re taking (or mandating) themselves are necessary.

Imagine PBOT employees driving to their office computers to run a PR campaign encouraging people to avoid unnecessary trips, when they could be (and would prefer to be) doing the same work from home.

Those are clearly the employees PBOT doesn’t need as they don’t contribute to the agency’s core mission.

The blogger Mr. Money Mustache also talks about how biking saves you a ton of money: Get Rich With… Bikes.

This is pretty stark. One trip out of every five makes that much of a difference? Cool! This is an achievable goal for the general population, and the kind of data that supports the two major components of increasing mode share: bike lanes and a friendly (or at least familiar) road culture that understands how to share it. One without the other does not work, and we must allocate funding accordingly! Man, can we distill this into how many trips per week people should aim to take by bike/walk/transit? Five? Seven? So one per day, or one full day of only biking?

Roger Geller, get your PR campaign funded! Do some polite driving PSAs! Do a “have you done your five trips by bike this week?” PSA!! A trip-chaining PSA! Winter/rain biking PSA! Bring in influencers for young people, new parents, careerists, parents of kids in sports, DINKS, LGBTQ+ crowds, empty nesters, retirees, etc on their social medias of choice! (Shoutout to Jenna Bikes and Coach Balto – they can’t do this work alone!)

City council/PBOT, get your network connections funded! Get the signage for the neighborhood greenways unified and up in people’s faces so we know where we’re going! Put the beg buttons in rational locations. Let us take up some SPACE on the road! Pass the e-bike subsidy! Raise parking prices! Build secure Heck, the city should pitch Columbia, Vvolt, Showers Pass, etc to chime in on their social media about how the best way to get around Portland is by bike with their gear, or sponsor a PSA!

Businesses, hit up PCEF or wherever for grants to put more and bike parking out!! Hotels, grow your stable of bikes for guests to use gratis and work with local tour groups to actually get people out there! Insurance companies, get a grip and insure businesses that want to rent out e-bikes! There are so many opportunities for partnerships.

We can do this!! We can really get people to do this. We can revive the culture of biking and build the best bike network in the country. The ideas exist, they just need to be executed without fear and without hedging. This requires money, yes, but maybe more importantly, a sense of adventure, courage, confidence, verve, and straight-up fun. Biking is f-ing cool, full stop. Come join the cool kids and have a good time!

Small order-of-magnitude correction:

“a 20% shift would prevent 25 metric tons of CO2”

That should be 26 million metric tons (cumulatively by 2050).