Lost amid the protests, politicking, and police statements at last week’s traffic safety press conference was a new report from Multnomah County that offers clear solutions to our staggering increase in crashes, deaths and injuries.

While Portland Transportation Commissioner Mingus Mapps said the focus of the event was to spark a “culture change” on our roads by focusing on individual behaviors, the County’s report recommends shifting away from behavior change and instead building a “safe system” by investing in safer road designs, changing laws to promote safer vehicles, funding health services to create safer vehicle users, and more.

For the first time ever, the County has gone beyond police records and engineering analyses to understand this problem. Instead, their report relied on data compiled from medical examiner investigation records. The report, Public Health Data Report: Traffic Crash Deaths in Multnomah County Taking a Safe System approach to address traffic-related fatality trends & contributing factors, digs into the data from 2020 and 2021 and comes at the problem from an epidemiological perspective.

At the press conference on Monday, Multnomah County Healthy Homes and Communities Manager Brendon Haggerty said the recent rise in traffic deaths and injuries is an “alarming situation.”

“It’s a leading cause of death, the trend is going up, and what’s especially alarming is that we see racial disparities,” Haggerty said in his remarks in front of City Hall.

The County’s report used data from 170 deaths and focused on several factors that influence crash injury severity: speed and roadway design; race, socio-economic and housing status; and use of intoxicants.

Excessive speed was found to be a factor in 42% of traffic crash deaths in 2020 and 2021. Over that same two-year time frame, the report found that a quarter of all traffic fatalities were homeless people and there’s twice the rate of traffic death among Black people as non-Hispanic whites. And when it comes to the use of intoxicants, four out of five victims tested positive for at least one. “That doesn’t necessarily indicate impairment,” Haggerty cautioned. “But it is a very high proportion.”

To turn things around, Haggerty said the answer is in the “safe systems” approach (of which the concept “vision zero” is just one element). Given the role of human behavior in traffic deaths, Haggerty said, “A critical insight of that approach is that humans make mistakes. And our system should be built so that when mistakes happen, they don’t result in serious injury.”

The County’s direct role will be to help people find more stable housing so they spend less time on the street exposed to high-risk intersections. They can also provide more behavior health and addiction support, so that people are in a healthier state when they get behind the wheel of a car.

On other measures, the County will have to use soft power to have an influence. This report is part of that effort.

Fewer people would die, the report found, if people would drive smaller cars. The report was one of the first from a local government agency to specifically identify the role larger, heavier cars have on the death toll. The County wants to work with state and city officials to increase the registration fee for heavier and taller, non-commercial vehicles.

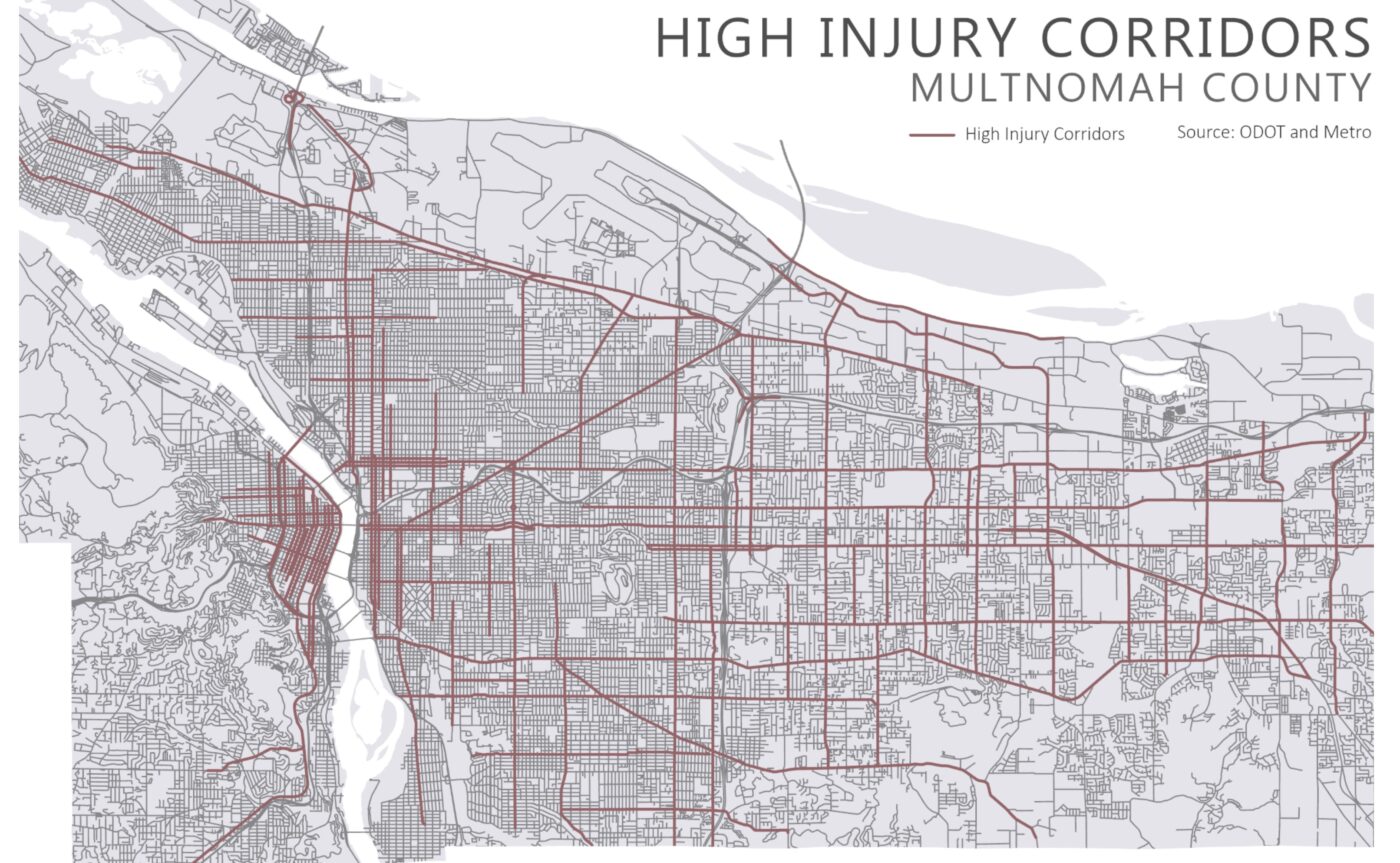

The report offers a range of detailed recommendations. The ones that caught my eyes were: a 30 mph, countywide urban street speed limit that would be supported by investments in proven traffic calming projects; automated enforcement cameras; the use of more unarmed traffic officers; statewide laws on speed-limiting technology and alcohol detection systems in vehicles; and political opposition to all projects that “increase or do not decrease” vehicle miles traveled.

If Commissioner Mapps was looking for a plan of action, this report from the County would be a great place to start. I highly recommend giving it a read. Find the full report here.