At a meeting of its Transportation Policy Advisory Committee (TPAC) on Friday (4/7), Metro made it clear they’d like to get into the e-bike purchase incentive game. They join the cities of Tigard and Portland, as well as Oregon lawmakers and the federal government in their enthusiasm to fill demand for e-bikes as weapons against climate change and as effective tools for personal and family mobility.

TPAC, which is made up of over a dozen technical staff from agencies and governments throughout the region, learned about the potential investment in e-bike access via a presentation about the federal Carbon Reduction Program. This $5.2 billion program was approved as part of President Joe Biden’s Bipartisan Infrastructure Law in November 2021 and is administered through the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) with a goal to, “fund projects designed to reduce transportation emissions.”

Oregon will receive about $82.5 million total from the Carbon Reduction Program. The Oregon Department of Transportation will hand out about $54 million of that, and Metro estimates they’ll have about $18.8 million total to spend over five years. At the TPAC meeting Friday, Metro said they plan to award five years in one allocation process. As part of that effort, they’ve developed several draft packages of projects that will be refined by TPAC, the Joint Policy Advisory Committee on Transportation (JPACT, which is sort of a TPAC for elected officials), and Metro Council members.

Those draft packages were revealed publicly for the first time Friday.

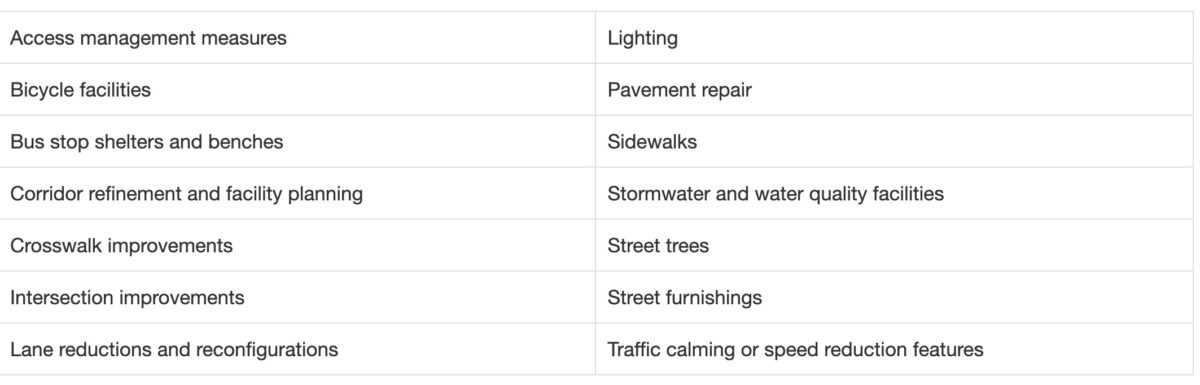

Metro has come up with four different packages that would guide this $18.8 million allocation. Three of the four include a strong tilt toward transit projects because Metro used their Climate Smart Strategy plan as the backbone for Carbon Reduction Program decision-making and transit came very highly recommended through that process.

As you can see in the graphic from the TPAC presentation, Packages A, B, and C include four projects each, with three of those being transit-related: bus rapid transit on 82nd and Tualatin-Valley Highway, and a transit signal priority project on TriMet Line 33 (McLoughlin Blvd). The only difference in those three packages is a $3 million investment into a fourth project. Package A would fund an e-bike program, Package B would invest in Safe Routes to School projects, and Package C would put that $3 million into a general Active Transportation pot. Package D would fund five projects that just missed out on funding in a recent Metro federal active transportation funding process (known as the Regional Flexible Funding Allocation, or RFFA). All four packages would set-aside $1.8 million for Metro’s Climate Smart implementation program.

It was the $3 million e-bike program that caught my eye as something new.

Here’s what the Metro presentation said about what it could fund:

Potential elements include a subsidy/rebate program, promotional campaign, and transit access elements such as secured parking with charging stations. Potential partnerships with local agencies and non-profit organizations and coordination with potential state rebate program under consideration by the Oregon legislature.

According to Metro Resource Development Section Manager Ted Leybold, the specific type of program has yet to be determined. “At this point, it is only a conceptual investment to support deployment and use of electric powered bicycles,” shared Leybold in an email to BikePortland. The program would be further defined only if Package A is recommended by JPACT, TPAC and Metro Council.

No TPAC members objected to the e-bike program at Friday’s meeting. One of them, Indigo Namkoong who represents environmental justice nonprofit Verde, said she’s an e-bike user and “fan” but warned that the barrier to more e-bike riders in the northeast Cully neighborhood her organization works in isn’t just about cost. “It’s about infrastructure and feeling and experiencing safety on the roads,” Namkoong said. “We don’t have bike lanes in a lot of areas in our neighborhoods in Cully and surrounding areas… so safety infrastructure is one of the most important hurdles that we hear about.”

Metro staff will return to TPAC and other advisory bodies in the coming months to seek an official recommendation on which package should move forward. It’s a relatively tight timeline because Metro needs to have their decision to FHWA by November of this year.

If Package A and the e-bike investment program is prioritized, Leybold says there will be several issues to work through including: restrictions with federal funds (that prohibit direct subsidy for private vehicles, “so we would need to get creative on how to use the funds to support deployment and use while still being compliant,” Leybold said) and how best to coordinate with other e-bike funding programs already being considered by the Oregon Legislature and the City of Portland.

Lawmakers in Salem are currently considering a bill (House Bill 2571) that would offer rebates to e-bike buyers in the amount of $400 or $1,200. That bill passed out of its first committee on March 29th and is currently in a budget committee. And the City of Portland is likely to use revenue from the Clean Energy Fund (PCEF) to establish an e-bike rebate program of its own. As we reported last month, a PCEF committee has recommended $20 million to increase e-bike access over the next five years.

If HB 2571 becomes law, Metro’s $3 million e-bike investment could be added to the “Electric Bicycle Incentive Fund” that bill would create. Or it could be a standalone program.

In addition to these three e-bike incentive efforts, there’s also the federal E-BIKE Act that was just reintroduced to Congress late last month. If signed into law, the E-BIKE Act would offer individual consumers a refundable 30% tax credit for purchasing an electric bicycle — up to a $1,500 credit for new bicycles less than $8,000. The credit would be allowed once per individual every three years, or twice for a joint-return couple buying two electric bicycles. Income caps of of $150,000 annually for single filers, and $225,000 for heads of households, and $300,000 for those filing jointly would apply.

Watch this space in May for final decisions about these draft packages at Metro. Any allocations would have to be amended into the Metropolitan Transportation Improvement Program before they could be spent; but no matter how you slice it, buying an e-bike is very likely to become much easier in the coming months.