The Hayhurst Neighborhood Association (HNA) has decided not to appeal the Hearings Officer’s November 8th decision to approve the Land Use permit for the proposed 263-dwelling subdivision of the Alpenrose Dairy site. After an emergency board meeting, held on November 20th, a little over a week after the group had voted to appeal the HO decision, the HNA decided ultimately not to file an appeal. No group or individual met the November 22nd appeal deadline, which means that the HO’s decision stands, and the Raleigh Crest development can move forward with its plans.

The HNA issued a press release early Friday evening which stated that they had, hours earlier, signed an agreement with Walter Remmers, an owner of Raleigh Crest LLC. The agreement covers, 1) monitoring the environmentally sensitive wildlife crossing at the southern end of the property and 2), funding a traffic study “to help support future safety improvements to SW Shattuck Road and its intersections, particularly the SW Illinois/60th intersection at the entrance to the new development.”

I spoke with HNA Chair Marita Ingalsbe Friday evening and she added some details to the press release.

Concerning the traffic study, the developer has agreed to fund up to $50,000 for the study, the scope and date to be determined by the HNA. This flexibility means that HNA could obtain real-world traffic information after the first phase of the development is built. The thinking is that real data, collected after a partial build-out of the housing, and years after any pandemic-related traffic depression, would better inform road safety improvements than the Trip Generation tables traffic engineers use for estimates.

Analysis

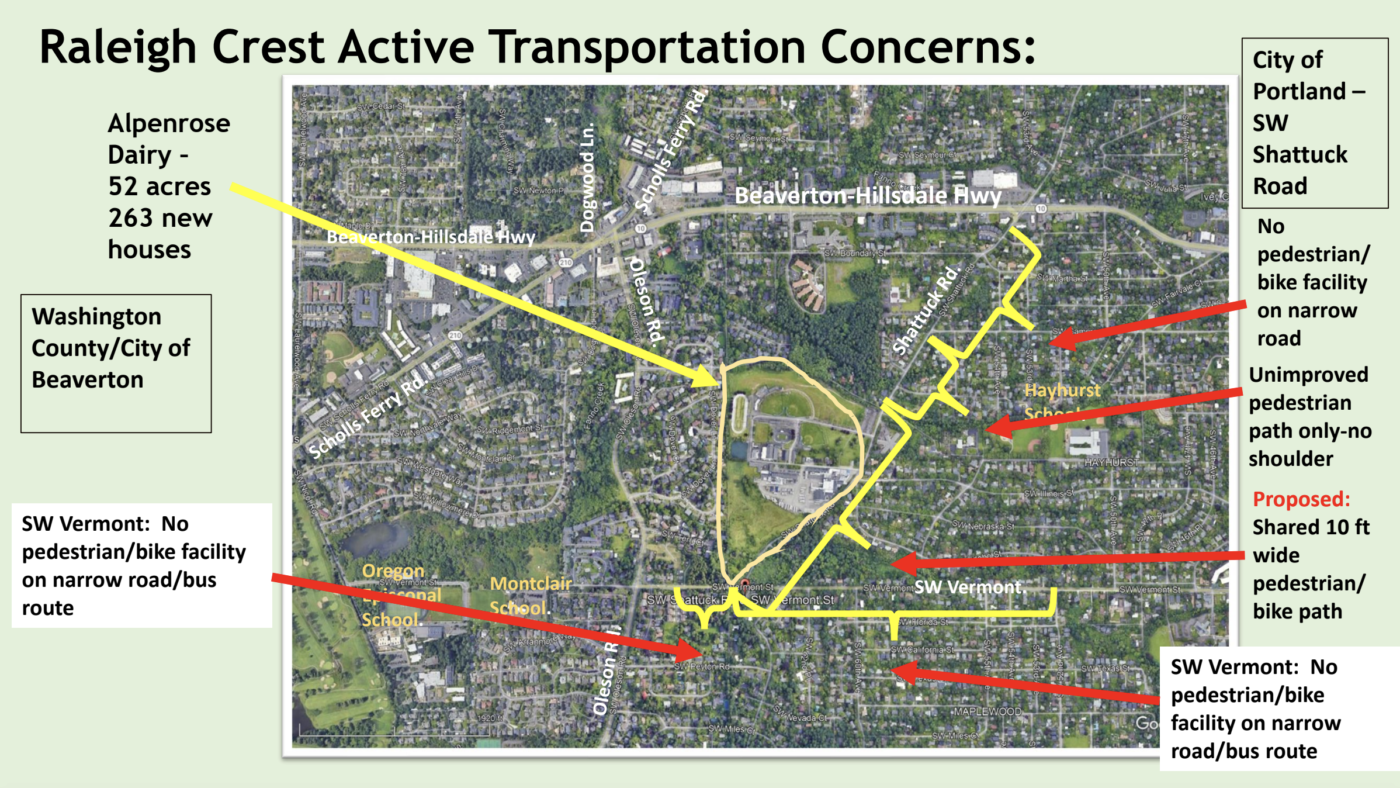

At first glance, it might seem that by backing off the appeal the NA has given up its leverage for obtaining safety improvements. Of particular issue has been the intersection of Shattuck Rd, Illinois St and 60th Ave, which sits at the entrance to the new development to the west, and to a Neighborhood Greenway and Safe Route to School to the east. The intersection would be the main route for elementary school children from the development to reach their school, Hayhurst Elementary, two blocks away.

The HO approved the Land Use (LU) permit without the stop signs or speed bumps that the developer’s traffic consultant had initially recommended for traffic calming.

It’s a gambit, but one possibly significant consequence of not holding up the LU permit is that it removes authority over the street design from the Public Infrastructure section of Portland Permitting and Development (PP&D) and puts it back in the domain of the Portland Bureau of Transportation (PBOT).

The pathway for transportation spending differs between capital projects (public money) and private development (developer money). Portlanders are mainly familiar with big capital projects, things like the “in Motion” plans and the 102nd Avenue Safety Corridor project. Those projects are designed by PBOT planners and funded with taxpayer money. They invite public input, and process and public outreach are a big part of the efforts

That is a world apart from the traffic mitigations and frontage improvements the city requires of developers. Most important, the group which oversees them is different. PP&D Transportation Development Review has a different design culture, and they are independent of the non-binding transportation policies the City of Portland has adopted — things like Vision Zero, Safe Routes to School, 15-minute neighborhoods and PedPDX.

Unlike PBOT, PP&D makes decisions with one eye on Nollan/Dolan jurisprudence (the developer appeals the decision) and the other eye on the Neighborhood Association, which can also appeal. A successful outcome for them is no appeals, and then the group moves on to the next project. They work under a lot of pressure to keep development moving forward and on schedule, and their right-of-way requirements are often minimal.

The region is like a puzzle with half the pieces missing, a disconnected network built piecemeal, development by development.

I don’t have the data to back this up, but I would say that most of southwest Portland’s right-of-way design is the product of the developer-funded pathway. That is probably why the southwest has, by far, the least sidewalk coverage and most disconnected bike network of any area in the city. The region is like a puzzle with half the pieces missing, a disconnected network built piecemeal, development by development.

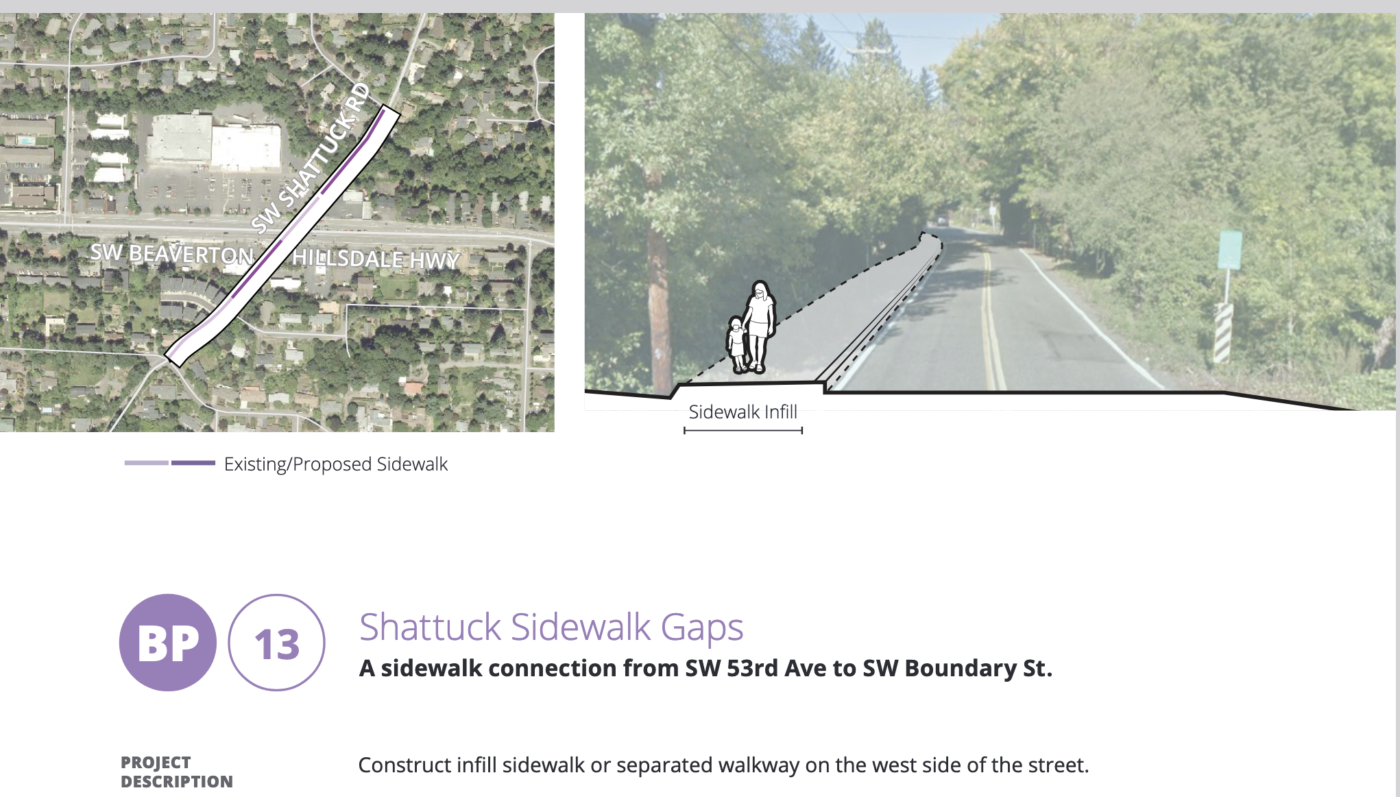

So putting Shattuck safety improvements in the hands of PBOT might have some advantages. From an advocate’s point of view, it opens up the discussion to other parties. Whether because of custom, courtesy or city code, transportation advocates defer to the NA in Land Use cases. That can shift once road improvements move out of the development realm. For example, there are a couple Southwest in Motion (SWIM) projects on Shattuck, and SWTrails has an interest in Shattuck because its Red Electric Trail crosses the road.

The change in authority means that the city will have to pay for any safety improvements, not the developer. But at stake in this disagreement were speed bumps and stop signs — not big-ticket items. And the most important safety improvement to the road — continuing pedestrian and bike facilities all the way to Beaverton-Hillsdale Highway — was never on the table with the developer. The city can’t expect a private land owner to foot the bill for decades of its infrastructure neglect, and Nollan/Dolan jurisprudence ensures that.

Another change which could work in favor of active transportation in southwest Portland is the new system of district representation. Many District 4 candidates made a point of following Shattuck and the Alpenrose development — more accountable representation and less politicized bureaus might shift how and where PBOT spends money.

If all goes well, Raleigh Crest could break ground in the summer of 2026. And my prediction is that our new City Council and Mayor will be focused on homelessness for their first year. So I don’t expect much more transportation news regarding SW Shattuck Road for a while.

Thanks for reading.

BikePortland has served this community with independent community journalism since 2005. We rely on subscriptions from readers like you to survive. Your financial support is vital in keeping this valuable resource alive and well.

Please subscribe today to strengthen and expand our work.

It would be nice if pbot would sign into an agreement to do significant interventions if a post construction traffic safety study indicates there are significant safety issues. I’m guessing they’ll sit on their hands.

The problem with the approach that is being taken is that pbot is basically bankrupt. They don’t have the money to redesign and build intersections. The developers do have money. Getting safety improvements before development is basically the only way to do it.

Despite the seeming good intentions of the neighborhood association and the developer, the failure of pp&d and pbot to act now means that a golden opportunity has been lost.

You’re right, Yut. In every other city I’ve lived in – and I’ve lived all over the country – the city compels developers to improve infrastructure before they can build. Developers have great incentive to create the improvements cuz they need to build and sell houses (all about da mun-nay mun-nay).

Only in Portland is the situation reversed – where developers tell the city to pound sand. It’s crazy, and it’s a big reason I’m moving out of Portland as soon as I can.

Municipalities across the country are limited to an extent in what they can require as a condition of development, determined by the Supreme Court cases, Noland, Dolan and Koontz (spelling?).

The point of Dolan/Nolan is that communities must be fair on how regulations are applied, that cities can’t have one set of willy-nilly requirements for one outside developer and another for well-connected insiders and homeowners, that all applicants need to be treated fairly, that all comp plans honored, and if you have a bike, beach, or other public amenity plan, that you mark where you want stuff beforehand and not afterwards when some new development opportunity comes in.

I grew up in a community (Grand Forks ND) that required that all sidewalks, gravel-lined concrete streets, lamp poles, utilities, water lines, sewers, and driveways for a development or subdivision be put in before a single house foundation was allowed to go in, and that all those items be inspected before, during and after development. Yeah, sure, it made houses, apartments, and commercial structures more expensive to build, but they lasted longer and the public infrastructure was far more usable and connected, even in poorer parts of town – and the outside developers would complain, but that was just the cost of building stuff in Grand Forks – and the rules were strictly applied to everyone. The community of 50,000 has a 50+ mile off-street paved path system that was built gradually, but steadily, useful for both bicycling year-round and for snowmobiles. No beaches, but a lot of river paths, several no-car concrete river bridges, and a huge concrete flood wall.

Meanwhile, Fargo ND is a bit like Portland, rapid growth and dirt-lined asphalt roads without sidewalks everywhere, but with the added bonus of 4-foot deep freeze/thaws that cause streets to buckle every winter.

Lisa has her rose-colored glasses on – PBOT has stated explicitly that money (when they have it) goes farther on the east side than it does on west, that equity scores prioriize projects – and SW scores badly in some areas, like Alpenose – and that the Krueger Doctrine is one huge road redo like Captol Highway per generation. Why on earth would people think PBOT woul put in the very speed bmps and stop signs the DEVELOPER offered to pay for, when PBOT said no to them doing so?

No money, no equity score, too expensive, and bureau hostility means we will have to wait till a child or cyclist is killed before the ASShto manual says it’s ok for PBOT to consider doing something. It will take a change in management before anything happens.

Perhaps what the developer and PBOT should have done was bring some of East Portland to Southwest? There’s a development south of Division on 125th that was put in 1993 with subsidized low-income housing, a mix of apartments, townhouses, and crap homes, and only one way out, no signal at Division for 25 years (they finally put one in for the TriMet bus project), two crime gangs fighting it out for 30 years now. If the developer had applied for 2,300 units instead of 230, I bet the city would put in a few stop signs, maybe even a sidewalk or two!

That sounds very cynical, David. Is there perhaps another explanation for what happened in the SE 125th development?

PBOT has put in speed bumps and bike lanes and other safety infrastructure in SW Portland in plenty of places like Shattuck Rd in recent years. Sure,they spend less money in SW Portland than East Portland, and that’s fine. But it’s not like they are averse to doing low-cost safety improvements like speed bumps in SW Portland.

Any speed bumps in ‘recent years’ have been the work of Fixing our Streets and Safe Routes To School, which are specific areas with specific metrics. And it’s no guarantee – I know of two projects where Alternative Review recently killed pedestrian safety improvements, despite the road being a designated SRTS street (the sick joke of an explanation on one was ‘the established neighborhood prectice’ of NOT having a sidewalk!).

PBOT is hostile to ped/bike efforts in SW unless they do a whole street re-do, like Capitol Highway; they say it constantly, like at Alpenrose, where they mentioned preferring corridor improvement over ‘spot treatment.’ With no money, and low equity score, Shattuck will not be getting a ‘corridor improvement’ any time soon. And if isn’t a SRTS stereet. despite the fact kids need to use it to get to some schools or bus stops.

How maddening!

Luckily, this will change with the new city government. Or so I hear.

Power of the purse?.Setting up new ‘safey division’ and giving most non-pothole -filling monies to it? Pressuring city manager to shake up management? Possibilities abound.

Do not comply in advance, Watts!

It sounds to me as if the technical side of things is pretty much played out. This is the sort of problem you used to be able to take a second swing at politically by contacting the commissioner in charge (and it would be especially powerful if the developer and the community approached together, as sounds possible in this case).

People tell me the new system will offer elected officials more leverage over PBOT, so in January perhaps folks can give this another shot.

Almost all of Portland including much of SW, the land and it’s resulting street network is part of the “Township and Range” land division system set up by Congress in the late 1700s, used heavily and almost exclusively in the West, Midwest, South Central, and even in parts of Alabama & Mississippi, whereby land is divided into 1-mile sections of 640 acres, then subdivided into 160-acre quarter sections, then 40-acre quarters of quarters. Division, Stark, 62nd, 82nd, 122nd, SW Vermont are all “section line roads”. The diagonal roadways are older routes, sometimes Indian trails (Powell, Sandy & Foster are known examples) while some others may be byproducts of early settlers using the East Coast (British “metes and bounds” land division system.

Back before streets were paved (pre-1890 generally) all of these were gravel-lined dirt roads that the neighbors would build and improve (usually farmers). Later when cities and counties started to add sewers and water lines, the roads would start to get constructed, but even in downtown there were plenty of mud streets – often the only paved streets were those paid by bicyclists through subscriptions. Most regular roadway construction by the city and county wasn’t until the early 1920s when cars started to become popular. Sidewalks came earlier, often before the street was paved, in rich developments where developers were trying to attract wealthier buyers – I’ve seen many old photos of Portland streets with sidewalks, a trolley rail, and a street full of mud and gravel – but most parts of Portland had no sidewalks at all until the federal WPA projects in the early 1930s.

From 2000 through 2006 I worked in the GIS mapping section of PBOT where we mapped sidewalks, streets, signage, easements, and whatnot – a very boring job – but we did have to regularly read county maps and roadway profiles to map all those “street features”. Nearly every section line road and most residential streets started out as Multnomah County designed streets or roads, even within some private developments, more or less east of 39th, north of Ainsworth, south of Duke, and all those west of Downtown – with some major exceptions. The County typically laid out enough right-of-way for a 20 to 24 foot roadway with 6 to 8 feet of sidewalk or drainage ditch on each side – a 40-foot right-of-way was pretty typical – and had a raised asphalt roadway over a water main down the center. Rural roads had ditches, urban roads had curbs and sewers but often lacked sidewalks. Most county roads were constructed this way between 1930 and 1960, but in the 60s and 70s many section line roads were massively widened into our modern stroads with federal grants.

In the 1950s and 1960s there was a major national movement by city fathers and engineers to increase personal traffic safety by not building any new sidewalks and by narrowing existing downtown sidewalks significantly – anyone walking is doing so at their own risk and they really ought to be getting around by car was the thinking at the time – and so those parts of Portland developed in the 1950s and 60s are the least likely to have sidewalks, including large parts of SW and East Portland.

Nice history lesson – thanks, David!

Do you have a source on Powell as a Native trail? I’ve read that about both Sandy and Foster, but was under the impression that Powell was a farm road. Of course, many farm roads also grew from Native trails, but I’ve never seen something about Powell specifically and I’d be curious to read more.

Inner Powell is a section-line road, more of a quarter of a quarter section line road, to about I-205, but the outer part was built upon an old Indian trail through a lot of swamp. It was named for early farmers in Gresham who settled around 1852 – it’s too easy to think that most roads radiated out from downtown Portland, but Powell was one of the few that radiated from Gresham towards Portland.

I thought the developer will pay for part of the improvements along the westside of Shattuck?

Yes Rick, that’s correct. Raleigh Crest has designed, and will be paying for the multi-use path along the full frontage of their property. They will also be building the Red Electric Trail across the northern end of their property. So they are doing some really good things, and the area will benefit from those improvements.

I just wish that the Red Electric Trail will enter SW Dover Street across from 6403 SW Dover because it is very steep in the far northwest corner of the Alpenrose property. I know when I will have a lightweight bicycle, I will climb over that white fence across from that house rather than riding down a steep hill with a very sharp turn just to get to Dover.

Think their current proposal is doing just that.

The RET will be ADA-compliant across the property, and also through anything parks designed to the east.

This seems crazy. New developments within two or three miles to the west of this property result in new sidewalks and street lamps.

Rick, are you making a sly point that Beaverton, just to the west, has a functional city gov’t, while Portland, “The City That Works,” does not? I would agree with that interpretation generally, but if Beaverton is subject to the same Oregon laws, court precedents, etc, how are they able to do more functional and seamless housing and transportation development, while CoP effs it up continually?

Even unincorporated Washington County has new developments in Raleigh Hills that bring new sidewalks and new street lamps over the last twenty years.

Serious question as I just don’t know, does Beaverton have the non-profit industry that Portland has?

If it doesn’t that could explain why as Portland government relies on non-profits to do much of the work that Portland city workers should be doing. And non-profits are going to do their task the cheapest way possible which equates to low quality and low function.

I’m not sure what Portland nonprofits have to do with anything discussed in the above article or the comments. Nonprofits are not doing permitting and land use approvals. They aren’t building roads or doing infrastructure safety improvements.

Seems to me like you’re trying to drag homeless services into the conversation. Or am I misreading you?

I grew up in SW and rode my bike, skateboarded and walked everywhere. Never thought anything of it. I remember being annoyed when the sidewalks when in on Sunset Blvd because what used to be a flat smooth-ok maybe not that smooth-shoulder now had a bunch of ups and downs to accommodate for driveways. That and the clicking of hard polyurethane wheels on the sidewalk was a crappy sensory experience. So we got pushed further out into the road than before.

There was a blind guy, however, who used a cane and walked down Sunset to Hillsdale every day. I hope the sidewalks were an improvement for him and the kids walking to school.

Anyways, I didn’t know how good bike infrastructure could be until I moved across the river. What SW lacks in sidewalks and bike lanes it makes up for in trails, but thankfully it’s not an either/or scenario. I say bring on any improvements we can get.

I can relate to your observation, Rock, about the incredible disparity between bike infra east and west of the river.

JM and Eva do a regular segment on the BP podcast about how they get from point A to point B by bike, which is interesting but always highlights for me how many ways there are to get places by bike, east of the river, and how few ways there are to get places by bike in SW. BP has a very “east of the river” perspective since that’s where JM lives (so good to have Lisa writing about development in SW).

I ride my bike on SW Shattuck almost daily, so I can say with great confidence that cars speed on that road with impunity. It is narrow and has curves and short sightlines.

Soon we’ll have 263 new families in 263 new houses, and hundreds of people driving hundreds more cars, all trying to get places quickly, and I predict someone (probably a kid) is going to get killed on that road.

Since the city didn’t calm traffic in the design, PBOT will then come in and reiterate their commitment to “Vision Zero” and retroactively take measures to calm the traffic and try to prevent another person from being killed. It’s just the way we do things in Portland.

PBOT would rather wait for the “tragedy” to occur, and then they will add a RFB crossing or some speed bumps with cutouts that every SUV can just blow through anyway.

Yep – the speed bumps are classic Performative Portland: designed to look like the city is doing something about speeding, when in fact it is doing nothing of the kind.

Come on, this is hardly some “performative Portland” problem. Speed bumps and other half measures to calm drivers are the norm in every single place in the country

Just because other cities are performative, why should we put up with Portland being so as well? We should demand better from our politicians and public workers. Being Woke and Performative are not good things.

Speed bumps are the surest sign of the lack of intelligent life on this planet. No one likes them, yet every driver speeds though neighborhoods until they are installed. If that’s not shortsighted stupidity, I don’t know what is. Then, when the bumps are installed, the same drivers curse the bumps they encouraged and swerve to the center to take the emergency vehicle line that the city insists must be there for firetrucks and the like. More of the same. If we travelled through the as if we lived in community with our neighbors, none of these reactive measures would be required. If we designed our transportation systems with the most vulnerable users in mind, I think we all might get where we wanted to be a little more efficiently.

I would love for a little sanity to be applied to the design of how we get around in Portland. Doesn’t seem to be happening, though. Sigh…

Stph

Settlements like this often seem disappointing in some ways, compared to seeing the neighbors dig in and possibly get more than what they settled for.

But the people involved know a lot more than anyone else. It could be the developer SHOULD do a lot more, but legally it may have been tough to achieve that. Also, there’s been an incredible amount of volunteer work to get to this point, and they did achieve something with the appeal and settlement.

One thing about appealing an approval is it creates a situation where the City and developer become allies, defending the decision. The appellants have to fight against both alone, going up against paid City staff, the City Attorney, the developer’s attorneys and consultants, etc.–and they have to do it as volunteers with no ability to hire lawyers or consultants without passing a collection hat around.

I’m glad they got some positive, informed coverage here, to at least make up for some of the “NIMBYs!”, “this is why housing is so expensive”, “this is why developers have left Portland”, etc. comments that came up even here.

Those are great insights about the process. Thanks!

Except that the developer initially suggested the city and developer split some costs

o Per PBOT’s Traffic Design Manual, the implementation of speed cushions would be an appropriate safety and traffic calming treatment along SW Shattuck Road.

o Based on the 85th percentile speeds collected in the Fall 2022 along this section of the street, the City could alternatively consider constructing the cushions prior to neighborhood construction. – Transportation Impact Anaylsis, page 2

Now, perhaps Remmers meant “PBOT pays and we take credit” – note the ‘hey, PBOT could put them in before we even get digging!’ line – but ‘collaborate’ to me implies some sort of cost-sharing is on the table. Speed bumps aren’t that expensive in the grand scheme of this project.

And from Beaverton:

So Beaverton felt comfortable that possibly requiring speed bumps wasn’t going to trigger Nollan/Dolan.

PBOT looked at the OFFER to help put in speed bumps and said “LOL no”

Everything you wrote could be true.

qqq, what more would you have the developer do? They are doing a wonderful job with the frontage and the RET across the property. They aren’t responsible for upgrading the surrounding area. Those decades of infrastructure neglect are on the city.

PBOT views many collectors in southwest as highways, vital connectors in the flow of car traffic. Cushions, stop signs, mess with that.

Re cct’s comment , the Beaverton side, the “Dovers,” are not mile-long through streets.

A few speed bumps, entirely within the length of Raleigh Crest’s ROW, would have been appropriate and similar to the Dovers treatment. PBOT nonetheless said NO.

No need to head west to Beaverton, Shattuck north of BHH has speed bumps.

Not necessarily anything. I was thinking more generally–that in appeals like this, even if the appellants know of things they think the developer should do, there are still reasons to drop the appeal and settle for something less.

Your “They aren’t responsible for upgrading the surrounding area” is saying pretty much what I was thinking of with my “legally it may have been tough to achieve that”–as in, even if a development may add impacts to the surrounding area, the law may not require (“they’re not responsible for”) them to address those. Or maybe (speaking generally again) the law MIGHT require it, but being able to prove that without an army of lawyers could be impossible, making settling a better option than going through with an appeal.

Good. It’s time for Portland to grow up and get realistic about housing demand. Not everyone wants to live in a 1 or 2 bedroom apartment next to a wine bar. People want single family homes with yards, parking, privacy and all the good stuff that we work hard for. It’s insane that activists and naysayers continue to doom-and-gloom about Chicken Little scenarios while Portland gets ever-more crowded and miserable, leading to more aggressive driving and road fatalities. We’re long overdue for a reckoning on what works and what doesn’t, and I hope more people realize that being a doomscrolling stick-in-the-mud doesn’t actually accomplish anything. Build baby, build!