In last Wednesday’s three-hour public hearing on the proposed Raleigh Crest development at Alpenrose, the two most significant words spoken were “nexus” and ”proportional.” Coming from Steven Hultberg, the attorney for Raleigh Crest LLC, they signaled that the developer would be pushing back against the most recent requirements from city staff.

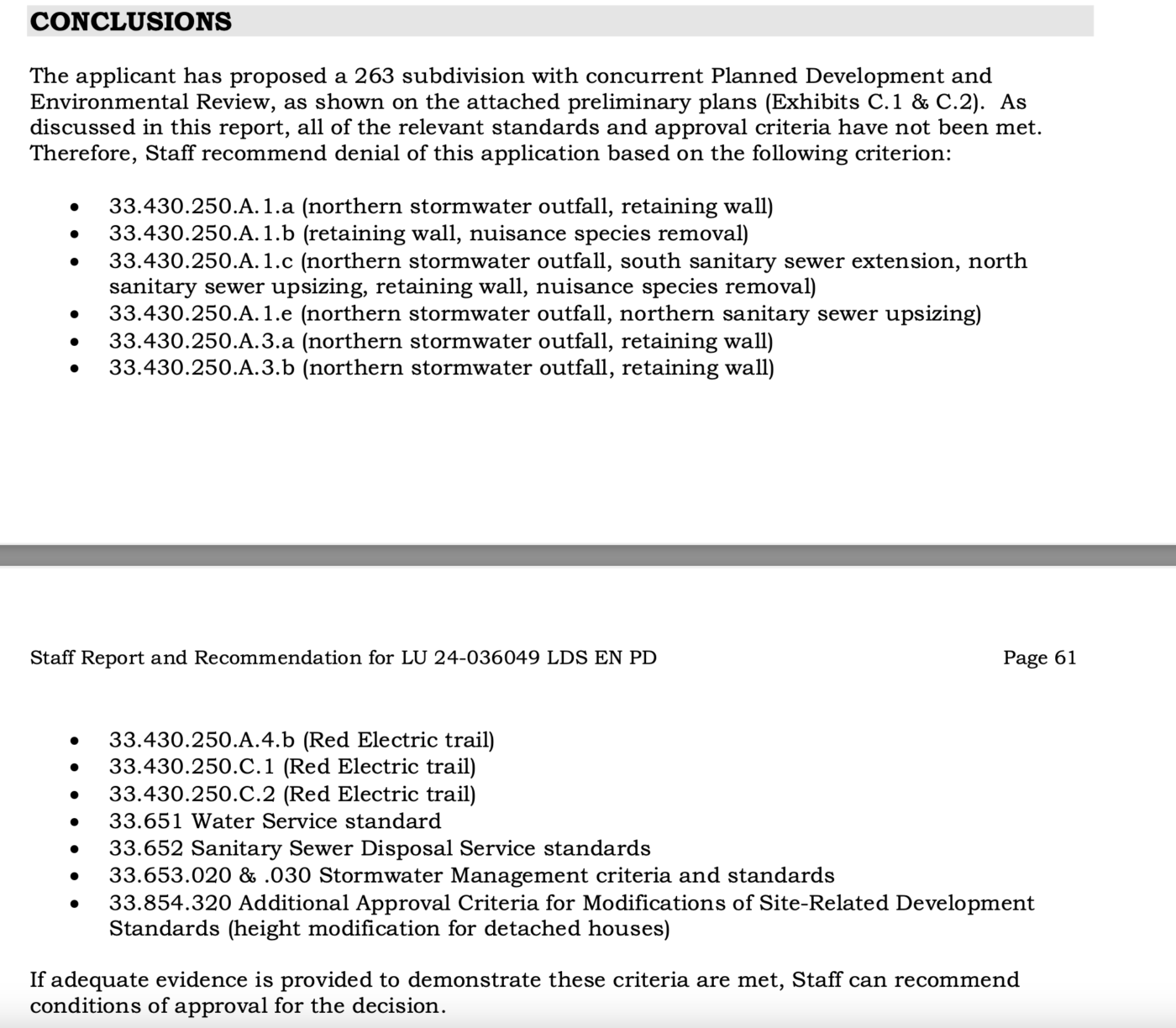

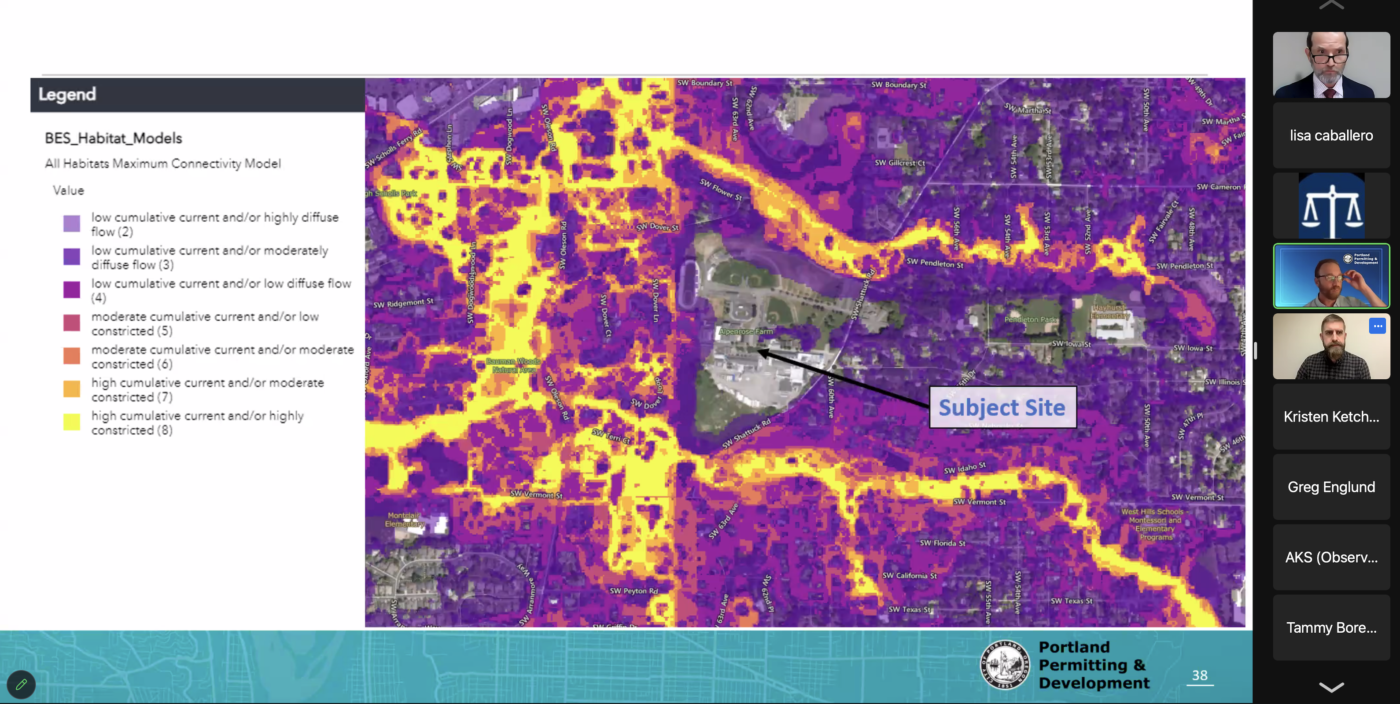

As BikePortland reported last week, city staff had recommended denying the Land Use permit for the proposed 263-unit Raleigh Crest development. In their Staff Report to the Hearings Officer, most of the “relevant standards and criteria” that had not been met pertained to either stormwater or other environmental concerns.

BES: Nexus and Proportionality

The terms “nexus” and “proportionality” refer to key concepts in a body of jurisprudence which limits how much a government can exact from a developer, and which is referred to as Nollan/Dolan, after the Supreme Court decisions in those two cases. By using those terms in his testimony, the mild-mannered Hultberg made it clear that his client had reached the limit of their compliance with certain city requirements, most specifically pertaining to environmental mitigation, and that they could possibly challenge these requests using Nollan/Dolan arguments.

Specifically, Hultberg brought up “nexus” with regard to the sensitive wetlands at the property’s southern tip. He argued that there was no connection, or “nexus,” between any possible harm caused by their work in the riparian environmental zone and the mitigation the city was requiring.

At first glance, writing about Nollan/Dolan might seem like a stretch for BikePortland, but really it isn’t. “Dolan” is Dolan v. City of Tigard, a 1994 US Supreme Court decision involving Tigard’s Fanno Creek Trail, a multi-use path (MUP) just downstream from the Alpenrose environmental zones. In fact, a section of the Red Electric Trail which is planned to cross the northern end of the Alpenrose site, will eventually connect with the Fanno Creek Trail. So the Nollan/Dolan cases are very much relevant to this proposed development, and are an invisible-to-the-uninitiated dominating presence in many Portland Land Use decisions.

This is the best summary of Nollan/Dolan I’ve read:

The Court’s decisions in Nollan and Dolan address the potential abuse of the permitting process by setting out a two-part test modeled on the unconstitutional conditions doctrine. First, permit conditions must have an “essential nexus” to the government’s land-use interest, ensuring that the government is acting to further its stated purpose, not leveraging its permitting monopoly to exact private property without paying for it. Second, permit conditions must have “rough proportionality” to the development’s impact on the land-use interest and may not require a landowner to give up (or pay) more than is necessary to mitigate harms resulting from new development.

2023 Syllabus prepared for the US Supreme Court

By using the words “nexus” and “proportional,” Hultberg became a soft-spoken rattler of some significant sabers.

The public’s turn

After the Staff and Developer had presented their cases against and for approving the permit, it was the public’s turn. The first speaker was Marita Ingalsbe, President of the Hayhurst Neighborhood Association and one of the founders of the Friends of Alpenrose advocacy group. She started by saying, “Our top concern is the lack of safe pedestrian and bicycling connectivity,” and she described deficiencies in the general area of the development, including lack of a sidewalk and bike lane between the site’s northern boundary and the Beaverton-Hillsdale Highway, and also the sidewalk gaps and absent bike lane on Vermont St to the south.

Let’s pause there a moment. Those comments were directed to the Portland Bureau of Transportation (PBOT), it’s not the developer’s responsibility to fix the city’s half-a-century neglect of the streets in the broader area.

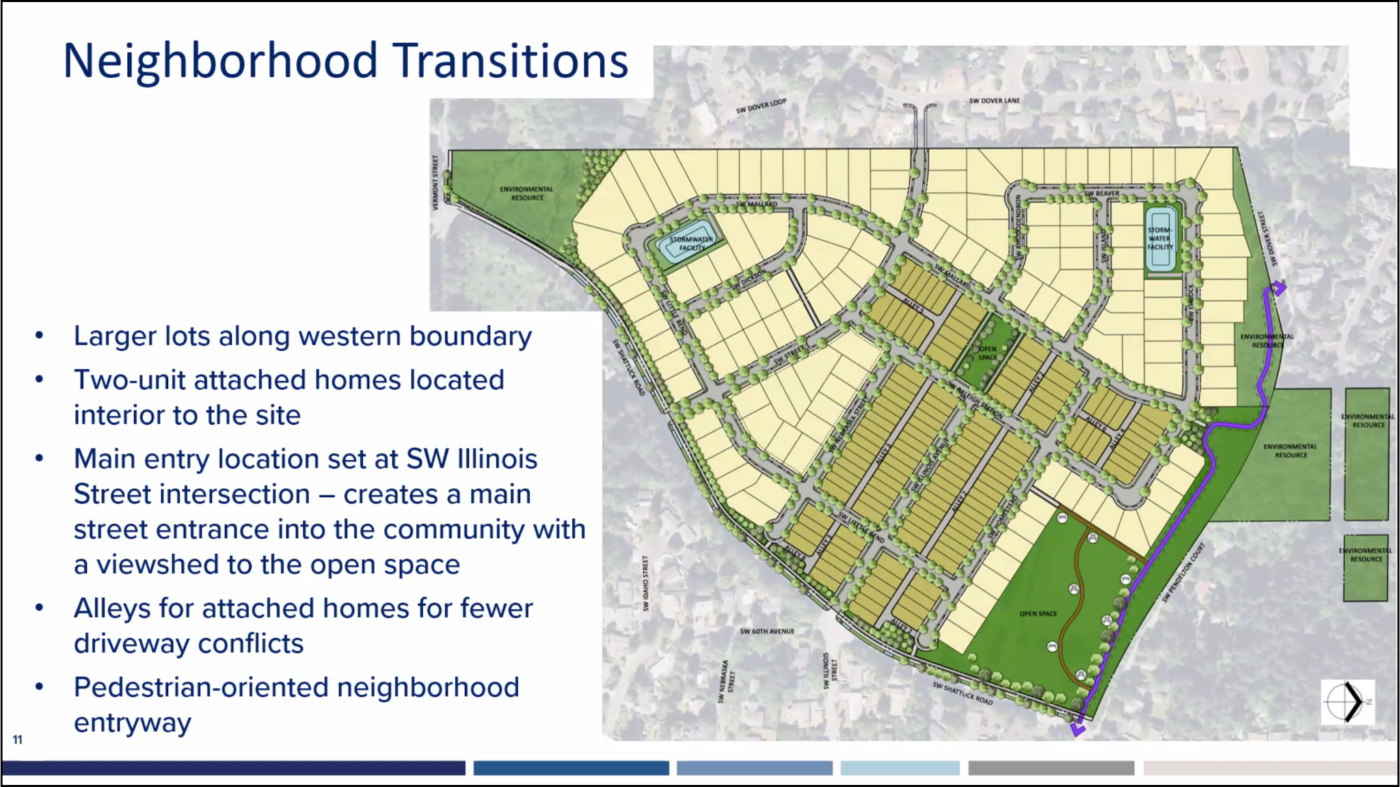

But Ingalsbe continued on with compelling testimony about many specific problem locations along the Alpenrose frontage which arguably could be the developer’s responsibility to improve or mitigate, if the city would require them to. For brevity, I’m going to highlight just one of those locations, the intersection of Illinois St and Shattuck Rd.

The intersection of SW Illinois St and Shattuck Rd

Illinois is southwest Portland’s longest greenway, and it is also Safe Routes to School (SRTS) designated. Currently, the road dead-ends at the Alpenrose Dairy in a “T” with Shattuck. The proposed development will add a new road traversing the development on Shattuck’s west side, and Illinois will become a through street connecting to it.

Inglesbe made a number of suggestions for improving what will become a complicated 5-legged intersection and concluded that, “some better design really needs to happen at this intersection when the new development goes in, we can’t just have a crosswalk.”

Or, as bike advocate Keith Liden wrote in one of his several letters to the city over the summer:

I am disappointed to see that the revised application continues to propose the same deficient pedestrian and bicycle designs as before. My descriptions of these problems and proposed solutions are contained in the attached emails.

(Read this PDF of Liden’s testimony at the hearing. It is an excellent critique of the proposed bicycle and pedestrian system, with suggestions for improving it.)

It was in response to these and other comments from the public that attorney Hultberg used the word “proportional,” but he also expressed a willingness to work with the city on “safety concerns that were addressed by a number of the commenters today,” saying that the developer is “more than happy to continue to discuss” them with the city.

PBOT: where’s transportation?

Given the public’s reasonable requests, and developer’s apparent willingness to discuss them, it is curious that PBOT has been so passive about requiring these public safety improvements, which would appear to meet the Nollan/Dolan nexus and proportionality tests.

Irregular, 5-legged meetings of several roads are pretty common in the southwest, and PBOT has excellent designers who are able arrive at low-cost solutions for making them safer. Readers might be surprised to learn that it is standard in Portland for the “Transportation” section of a Staff Report to be copied straight from the “Traffic Impact Analysis” of the developer’s traffic consultant, with the following paragraph tacked on at the end:

PBOT has reviewed and concurs with the information supplied and the methodology, assumptions and conclusions made by the applicant’s traffic consultant. As noted in the findings, mitigation is necessary for the transportation system to be capable of supporting the proposed development in addition to the existing uses in the area. Subject to the recommended conditions of approval, these criteria are met.

The only “condition of approval” PBOT has required of the Shattuck intersection with Illinois is a crosswalk and “appropriate signage.”

I don’t know where the siloes fall within the PBOT organization, but looking from the outside, it doesn’t appear that the desk tasked with PBOT’s development review has access to PBOT’s street design staff—the people who design capital, SRTS, Vision Zero, bike and other projects. Rather, the development review group (now working under Portland Permitting and Development) seem to limit themselves to approving or disapproving the proposals made by the developer’s traffic engineer. So PBOT’s wealth of experience and values around safety, active transportation and street design goes untapped with private development projects. This might be why the street improvements associated with private development often seem inadequate.

Timeline

The Hearings Officer has kept the record open to new evidence and comments for another 14 days past the hearing date. Following that there will be a rebuttal period until October 23rd. Following the rebuttal, the Hearings Officer has 17 days to deliver his decision about whether to grant a Land Use permit for the proposed Raleigh Crest development, on November 8th.

— Read more BikePortland coverage of the Alpenrose Development, here.

Thanks for reading.

BikePortland has served this community with independent community journalism since 2005. We rely on subscriptions from readers like you to survive. Your financial support is vital in keeping this valuable resource alive and well.

Please subscribe today to strengthen and expand our work.

Thank you for keeping the public informed about one of the larger residential projects underway in the city of Portland. These are done in Washington County without drama all the time.

A bike and ped connection with a curb to Beaverton-Hillsdale is a must. Maybe one side is the sidewalk, and the other is a 2-way bike and micromobility lane.

The SDC for this project is substantial. PBOT is completely empowered to dedicate it to completing bike and ped connections. It may also be the case the BES SDC can meet the stormwater needs the city wants and stormwater improvements, including bioswales for a curbed sidewalk.

Let’s hope the NA and Friends of Alpenrose can negotiate support from Shattuck neighbors for an improvement paid for by the SDC which improves their property values. Certainly the Capitol Highway improvements are an example, and this project does not need to be that deluxe.

Nothing ‘passive’ about it – it’s outright active hostility amongst some in PBOT management to pedestrians and cyclists in SW; most likely management at Development Review or those running the Altrernative Review process.

It is a CHOICE to look at a situation that clearly will be hazardouse for all modes of transportation, clearly needs addressed, and CLEARLY has a strong case for passing Nollan/Dolan for the simple fact that there are now many cars slated to enter from a new direction and say “Just slap a crosswalk on there; $*#% ’em.”

I would wager that two stops signs placed on Shattuck to make this intersection an all-way stop and increase pedestrian safety would cost about the same as striping a crosswalk, so this really is egregious.

There would be a lot more push back by the city and PBOT if the developer was proposing a new Pearl District or some other high-density development, let alone a corporate center, a rendering plant, or a shopping district. The fact is, the developer is proposing a very modest and non-controversial low-density residential development well within the suburban style of SW Portland. And as you say, it’s the city that has been negligent for so long, not the land owner or the developer.

You’re missing the point of “proportionality,” and there is nothing “modest” about 263 new housing units, nor is it “non-controversial,” come on, it’s been controversial every step of the way!

The proposed development will have an impact on the surrounding area and the developer has been very cooperative in recognizing that, and has engendered good-will with the MUP and Red Electric Trail. So why isn’t PBOT’s review staff asking for an obvious, low-hanging intersection improvement at Illinois?

Might it be because the intersection is physically just outside of the project area, in public right-of-way? Development Review deals with the land outside of ROW, though they do on occasion add to that ROW through dedications and easements, but the DR staff I know go out of their way to avoid doing anything with land outside of their jurisdiction – they don’t want that kind of controversy, they worry it may cost them their job or at least a promotion.

It’s not outside their jurisdiction, and requiring an update to the main intersection which feeds into the new development should not be a reach.

I think you’re misunderstanding what PBOT and other reviewers do. They regularly look at things outside the project site (the ownership the project is on) and require the project to do things there–sidewalk improvements, street trees, utility upgrades, driveways, etc. It’s not going to cost anyone their jobs or promotion, and it’s certainly not outside their jurisdiction–it’s a basic function of their job.

PBOT especially goes further, to parts of the transportation infrastructure like this intersection (ESPECIALLY like this intersection, since it’s as close as it could possibly be to the property) that the project may impact.

Well, the person who made NOT asking developers to do things SW policy was promted to running aspects of the development process citywide, so I’d wager lower staff can take a hint.

I could see the logic of ‘we can’t make the developer fix the Illinois side, as proportinately few development residents are expected to drive through it,’ but pretending they will have little effect on SW Shattuck and just requiring a crosswalk borders on insane. All-way stop signs should have been de minimus. I’m sure someone at PBOT will quote a disproven study that stop signs make pedestrians less safe or some such, or that AASHTO rules forbid inconveniencing a driver…

Why not solve the 5-legged intersection with high speeds and low sightlines with a roundabout? They are know to be safe and effective at reducing traffic deaths. We alrrady have several intersections of doom in SW (like the Raleigh Hills intersection of BH Hwy, Oleson and Scholls Ferry) that could be vastly improved with roundabouts. These would be costly of course, but here at Ilinois and Shattuck that could be added easily.

Keith Liden’s prepared testimony was very readable, and seemed convincing. Impressive work.

One comment (about the City wondering why more people don’t ride bikes) made me think of both the City’s elected leaders and the City’s voters in a new light: I think *both* the elected leaders and voters are overstating their support for policies related to bicycle safety, pedestrian safety and CO2 reductions.

I’d argue that we have a lot of preference falsification around these issues.

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Preference_falsification

The way I see it, the elected leaders are representing voters’ preferences pretty well: most voters like the sound of “let’s fight climate change,” and like the sound of “pro-bike,” but aren’t personally invested in either cause.

I mean that literally. What amount of their own money would voters be willing to spend on climate mitigation? Voters are more enthusiastic about taxing “rich people” or “corporations” to fight climate change, but directly taxing the middle class is clearly unpopular.

Similarly, many local people like bikes and want safety for riders… but clearly there’s a good bit of local pushback against new bike lanes, or other safety treatments.

Surely, some of these are not the same people! I mean, many people who oppose bike lanes also don’t give a hoot about bike riders’ safety.

However, I think there’s some overlap: how often do we hear someone say “I’m a bike rider, too, but bike lanes are not a good fit for my street because we need on-street parking.”

As regards elected leaders, I’ve never gotten the sense that any are *particularly* invested in cycling as a solution to our problems.

Many are of course happy to sign off on some amount of funding for safety improvements, and some have even gone to bat on controversial issues (Sam Adams over BES funding, iirc; Hales on off-road cycling). But more often we have examples of public support and behind-the-scenes disinterest or opposition (Hardesty, Mapps, Fritz).

Perhaps I’m being too cynical about this. Even if it’s not as strong as preference falsification, I’d still argue that politicians and voters overstate their support for cycling and climate mitigation. Most local voters want to think of themselves as environmentally-minded citizens, so candidates flatter us by adopting “pro-bike” positions, etc. That’s the mechanism by which the transportation safety hierarchy adopted by the full City Council, but is ignored (as Liden expertly points out) when it comes to accommodating the housing development at Alpenrose.

I do not mean this as some kind of denunciation of rank hypocrisy! I think bike/pedestrian safety and climate mitigation are hard and expensive nuts to crack. There are differences in impact that create entrenched opposition to change, and fully funded solutions would require enormous sums of money.

It’s no surprise that some people feel hopeless, or conversely, that some people maintain a kind of blissful ignorance as to the true costs of either project. Most of us feel “on edge” to one degree or another. Who really feels economically secure? Secure enough to devote a substantial part of our income to climate mitigations? Few people feel physically secure enough to risk commuting by bike, much less give up owning a car.

Even then, we’d still like to see positive change… just as long as it doesn’t cost us too much.

Yep – you’ve put your finger on why city councilors and PBOT staff show up for Sunday Parkways in SW to be photographed on bikes. And we never ever see them on a bike again.

Rene Gonzalez is a rare exception: a city councilor who actually gets around by bike, when cameras aren’t around, and doesn’t make a big deal about it.

They do – just over on the east side. The SDC is a slush fund, and the bulk of it – as far as I can tell – gets hied off to projects elsewhere, or dumped into mega projects like Capitol Highway. Lisa, no doubt, has the numbers somewhere; IIRC, SW gets something like 40% return of SDC charges put in, but it gets used up quick in the big projects. This is why SWIM is basically an unfunded mandate from PBOT – a (not particularly inspirational) ) asperational band aid. The priority projects over on the east side use most dollars from developments on west side.

I am happy to eat crow if I have remembered wrong! Sadly, the laws state you can’t keep the SDC money in the area it was generated.

This connection is something that a functional city, with politicians who act on their campaign promises (as noted elsewhere, ours tend not), and bureaus who do not view some areas with hostility, could be brainstorming solutions for. But Portland, and PBOT, prefer to do nothing, if nothing is easy,

Vote for council members who understand transpo issues. With RCV, you might get a couple!

My personal suspicion is that while some brave souls at BES took their job seriously, and pitched a good case to their bosses that losing an N/D lawsuit was worth the risk to prevent further harm to the environment, II bet someone at PBOT was afraid that if they required more than a crosswalk and got sued they’d WIN. PBOT would be screwed. No way do they want precedent set to give people in SW more than an unpaved shoulder…

“I don’t know where the siloes fall within the PBOT organization, but looking from the outside, it doesn’t appear that the desk tasked with PBOT’s development review has access to PBOT’s street design staff—the people who design capital, SRTS, Vision Zero, bike and other projects. Rather, the development review group (now working under Portland Permitting and Development) seem to limit themselves to approving or disapproving the proposals made by the developer’s traffic engineer. So PBOT’s wealth of experience and values around safety, active transportation and street design goes untapped with private development projects.”

That seems to have been the specific intent of Carmen Rubio’s plan to unify the permitting functions under a single bureau where the permitting employees do not interact on a daily basis with their peers who have a broader view.

Yes – let’s do bad development faster.

Richard is on to something – I’m sure Lisa knows the specifics better than I, but I believe a major issue in BDS taking so long to approve permits was Development Review at PBOT. “Streamlining” the process usually means cutting out things that slowed it, like details.

Not sure what you’re talking about, cct. Fire was notoriously slow according to the graphs I’ve seen.

Did DR not get caled out for taking a long time? I thought you even wrote about it. They weren’t the only ones, obviously, but my impression was they were a major delay. Claim happily withdrawn with proof to contrary! Like those graphs…

Can’t prove a negative, but if you google for my Housing Regulatory Reform posts, I think one of them has a chart showing the average times it take the various permitting bureaus to turnaround their work. I’m not going to look for it, but as I remember PBOT did pretty well, Fire was the foot-dragger that slowed the works down.

This https://bikeportland.org/2024/04/30/new-city-bureau-will-take-development-review-function-away-from-pbot-385974 is prbably what put me in that mindframe – “take away” seems punitive. I checked the city’s info

https://www.portland.gov/audit-services/news/2021/3/23/building-permit-review-audit and PBOT was smack in the middle for delays.

Claim withdrawn. Standing firm on giving fox key to henhouse, tho.

If the developer agrees on the record to constructing improvements, city staff and the hearings officer should absolutely be able to add them as conditions of approval. However ‘willing to discuss’ is noncommittal, and isn’t a response that should make city staff immediately reconsider their recommendation. Also, it’s a bit knee-jerk to say city staff is being passive in response to what’s said during a land use hearing. That can sometimes be the first instance that staff hears an applicant’s direct response to testimony. The record is still open and staff may revise things in response.

There are more recent cases in the Nolan/Dolan lineage that could explain a less aggressive approach when it comes to transportation requirements.

Most recently, the 2024 Sheetz decision applies nexus and proportionality to SDCs. Prior to that decision, SDCs were usually categorized as more of a non-discretionary tax, which shielded them from heightened scrutiny and the Nollan/Dolan tests. They are now an exaction that needs to be factored into proportionality. It clearly becomes more difficult (though not impossible) to meet Dolan when the size of the ‘exaction pie’ increases.

Another is the 2019 Knick decision. The key outcome of that ruling is that takings claims can proceed directly to federal court as a civil rights lawsuit, and do not have to exhaust local appeals before doing so. Defending a takings claim at LUBA (a typical first step for appeals of a city’s final land use decision in Oregon) is relatively inexpensive and not costly if the city doesn’t prevail. Defending a civil rights claim is much more expensive and damages can be astronomical.

I have no idea to what extent these are factoring into city staff’s recommendations, if at all. Takings jurisprudence is generally making it easier on developers and harder on local governments when it comes to requiring public infrastructure. There are very real reasons why the city might not to push the envelope.