In response to climate and transportation activists who are wary of expanding I-5, both Interstate Bridge Replacement Program (IBRP) leadership and politicians who voted ‘aye’ on the project have gestured to a consolation prize. IBRP planners – correctly – point out that the current bridge is unfriendly to people using active transportation, given the small path dedicated to biking and walking with dangerous gaps and little protection against the three lanes of car traffic in either direction. They say the vehicle lane expansion is just part of the project, and that it will also include improved facilities for people to walk, bike and roll between Portland and Vancouver.

But what good is nice infrastructure if it’s too steep to easily use?

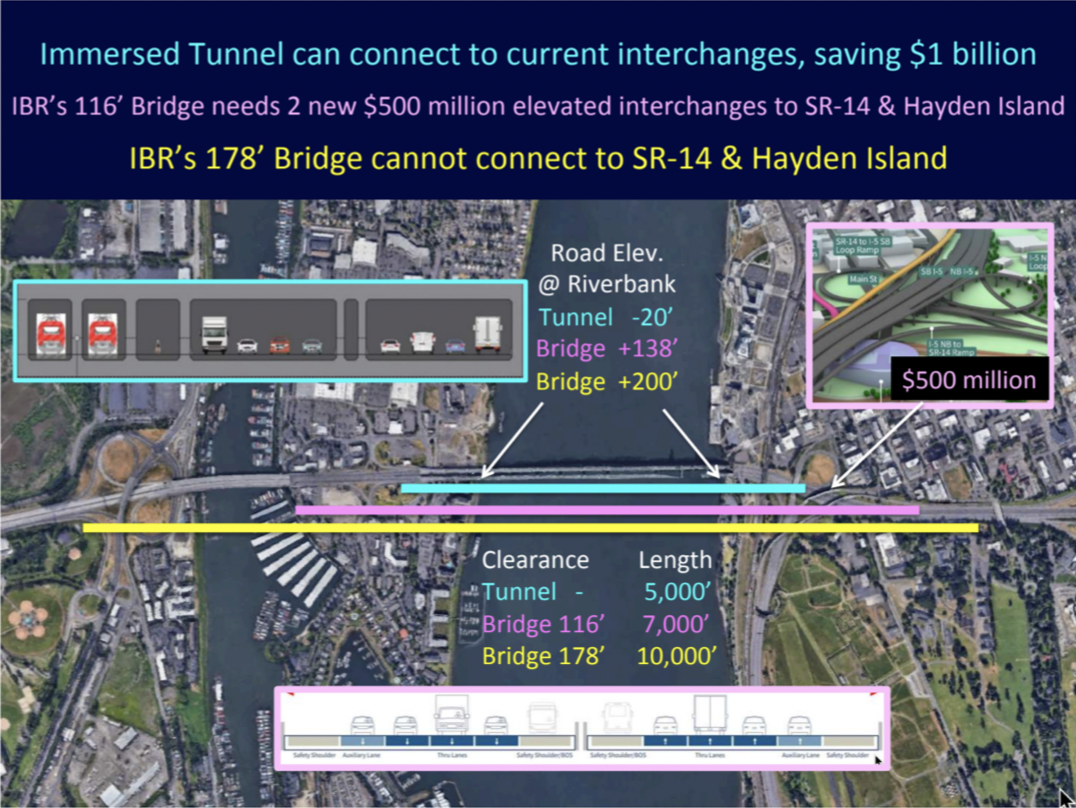

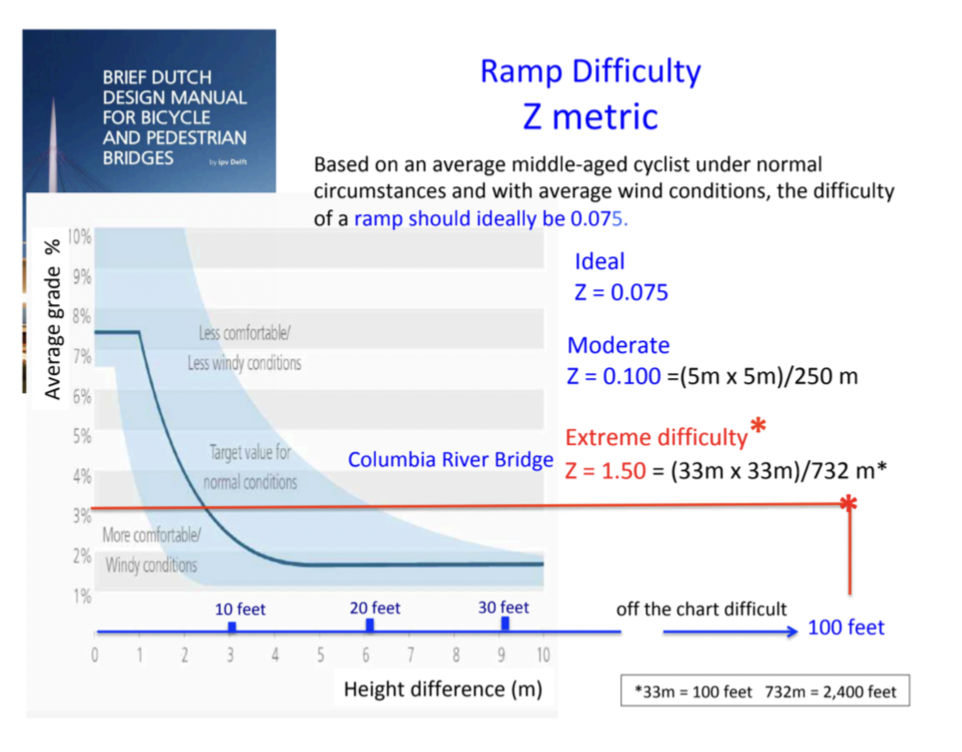

Just before Portland-area government agencies were set to vote on the IBRP’s Locally Preferred Alternative, the U.S. Coast Guard wrote a letter to project staff saying the replacement bridge design will need to provide at least 178 feet of vertical space so large ships can pass underneath. Transportation advocates already bristled at the idea of asking bicyclists to climb 116 feet as called for in the LPA design. An additional 50+ feet of height makes the situation even more dire.

The Problem With a Tall Bridge

Engineers have two options to ensure bridges have manageable grades: go low or go long. Biking across the existing I-5 bridge is far from ideal, but because it has a lift span to accommodate shipping vessels, at least it’s not very high off the ground (about 72-feet high). Getting from the ground to the bridge doesn’t require a significant climb, and the bridge doesn’t extend too far past the river.

With a fixed height of 178 feet, however, a bridge would have to be very long – about two miles – in order to meet the grade requirement of 4%. This would have an especially profound impact on downtown Vancouver, which is located just on the other side of the bridge. Even a 116-foot-tall bridge will require completely new infrastructure. And a 4% climb over two miles is nothing to scoff at in itself.

As a comparison, Portland’s Tilikum Crossing has an average incline of just under 5% for about a third of a mile, and this can feel difficult to traverse on tired legs. But the Tilikum Crossing, devoid of car traffic, makes up for the climb. I can’t imagine pedaling across a freeway bridge for two miles with the roar of traffic in your ear could provide that same balance.

To transportation and climate activists, this is just another example of the IBRP hastily pushing forward with a freeway expansion with not enough attention paid to the needs of people who aren’t in cars.

The Skeptics

Ahead of the City of Portland vote to support the bridge, members of the Portland bicycle and pedestrian advisory committees wrote a joint letter (PDF) to city leadership to hold off on supporting the project until they can make sure the height will “accommodate the 8-80 year old cyclist and allow for wheelchair users to access the bridge without significant effort.” The letter says mockups of the project area “gloss over the impact of height,” which makes it difficult to fully evaluate the sufficiency of walking, biking and rolling facilities.

When Just Crossing Alliance issued an action alert asking Metro at Portland City Council to force the IBRP to include more bridge design options in the LPA, the first point on their list was that it have, “gentler grades for freight and people walking, rolling and biking.”

IBR program leaders maintain the bridge will be manageable for people walking, biking and rolling – and also say they’ll be able to negotiate with the Coast Guard to keep it at 116 feet. But economist and IBR data watchdog Joe Cortright thinks they’re downplaying the seriousness of the Coast Guard’s requirement.

“The Coast Guard’s conclusion makes it clear that it is strongly committed to maintaining the existing river clearance, that it won’t approve a 116 foot bridge, and that the economic effects of this would be unacceptable,” Cortright wrote in City Observatory earlier this month. “Still, the [Oregon and Washington State Departments of Transportation] are equivocating, implying that the Coast Guard decision has no weight…and implying that the Departments of Transportation and not the Coast Guard are the ones who determine the minimum navigation clearance.”

IBR administrator Greg Johnson says they can’t use a different design like a tunnel or lift feature – both of which the Coast Guard suggests as feasible alternatives – citing logistical problems that critics dispute.

Retired engineer Bob Ortblad, one of the IBRP’s most outspoken critics, has been strongly advocating for an immersed tube tunnel concept in part because he says it solves the incline problem. Ortblad has investigated Dutch design manuals for best practices in designing bridges suited to bicyclists, and he found that considering the height and length of the IBRP, they would deem the strenuousness of this bridge unfathomable. According to the Dutch, an average grade of 4% is only acceptable if the bridge is 10 feet off the ground. Anything taller than that should max out at under 2%.

Any improved active transportation facilities will gather dust if the bridge is too high. A would-be Vancouver to Portland bike commuter may peer up at a path 178 feet in the air and decide it’d just be easier to drive a car.

Thanks for reading.

BikePortland has served this community with independent community journalism since 2005. We rely on subscriptions from readers like you to survive. Your financial support is vital in keeping this valuable resource alive and well.

Please subscribe today to strengthen and expand our work.

Exactly this! I occasionally biked the existing bridge when I worked in downtown Vancouver, and it is/was terrible, but this replacement is somehow more terrible still. I hate seeing the project engineers and electeds touting the new multimodal infrastructure as a “win” or a reason to proceed with this terrible bridge replacement and freeway widening project. Don’t bike wash this project!

I do wonder if “good” bike/walk infrastructure on an interstate highway facility is even possible though. Are there any examples of projects that truly appeal to the 8-80 year old demographic? I have a hard time imagining how any facility that close to a freeway could ever be pleasant, though they could certainly be less hard than the proposed steep climb.

I’m in favor of a totally separate multimodal bridge, aka Tillikum over the Columbia, coupled with some seismic improvements to the existing bridge, and none of the rest of this lane widening nonsense.

We can “enjoy” the full experience first-hand, with no imagination needed, on the Glenn Jackson (I-205) bridge. Steep, long, windy, and SO NOISY!

Given the practical limitations from the location of the bridge, it definitely seems like this bridge can’t be all things. At least if light rail were added, bikes could take that across and continue on.

No, ED, I really can’t think of any MUPs on any interstate bridges that are pleasant to ride on. They are always narrow and noisy and subject to frequent conflict with other cyclists or walkers. But my feeling has always been that I’m lucky to have ANY PATH AT ALL – let alone a pleasant one.

If I were the transportation czar, I would turn Hwy 30 into I-5 and build a new bridge at St Helens – make it 200 feet high. Turn the current I-5 bridge into a local bridge for transit, bikes, and walkers only. You heard it here first.

I am disapoointed that our leadership is willing to back ODOT’s plan. By downplaying the Coast Guard’s height requirement and saying they can find a way to negotiate, that are are immplying that that they intend to spend 100’s of millions of dollars to buy out the river-based businesses and purchase/modify Coast Guard equipment. That is what the CRC project was proposing, though the Coast Guard never bought off on it. That is sucha shameful waste of money plus a permanent limitation on river-based businesses. Our leadership should be invested in converving our funds and protecting our current and future businesses and mitigating climate impacts. Why not compel ODOT to explore the tunnel option? They are all just so bad.

Because the GOP has said they would “defund every facet of the U.S. government” if returned to office, this bridge is likely never to be built.

I could bike the grade but I wouldn’t do it just because I’m scared of heights and can’t imagine being 178 ft up with all that traffic and getting hit by crosswinds. No thanks.

For a couple points of local context, the St. John’s Bridge has clearance below of 205 ft (per Wikipedia), although the approaches at both ends are considerably higher than the banks of the Columbia River. The Glenn Jackson (I-205) bridge has clearance below of only 144 ft, and it already seems huge. It would be a monstrosity to put a bridge with 178 ft of clearance between Hayden Island and downtown Vancouver. (Note that the 178 ft proposal appears to be based on the current clearance of the Interstate Bridge with the spans lifted.)

There is no serious proposal to build a bridge at 178′. That would interfere with Pearson Airport’s flight path. It sounds like the Coast Guard is pushing for a bascule bridge, but it would be one of the largest in the world if they require to span the full 300′ wide channel.

The largest bascule bridge costed 173 million euros in 2011 with a span of 307ft. Burnside bridge, also a bascule bridge has a span of 251ft.

Sounds like it would be a lot cheaper than rebuilding a bunch of interchanges and building at an egregious height. But then ODOT wouldn’t be able to do a 5 mile freeway expansion so now its “unfeasible”.

The FAA has no legal authority to limit bridge heights. It can require warning lights on the bridge, that’s all. The current river channel is just 230′ wide (controlled by the width of the swing span of the downstream BN Rail Bridge).

ODOT is claiming that a new lift span would have to have a wider clearance than the existing bridge (something USCG hasn’t decided), but that it will somehow be allowed to build a fixed span that will be 62 feet shorter than the current bridge (something that the USCG has determined is “an unreasonable restriction on navigation.”)

Also: The USCG forced VA and MD to construct a bascule lift bridge for I-95 in Washington DC, which carries roughly twice as many vehicles per day as the I-5 briges.

https://cityobservatory.org/oregon-and-washington-dots-plan-too-low-a-bridge-again/.

I am inclined (pardon the pun) to believe that the height will be whatever the USCG wants. Navigational Supremacy has been a pretty standard legal theory and as long as the USCG says “we need this height” they are likely to get it. Even “we think we may need this height someday” is a strong legal argument. If they are going to build it then it’s probably time to start looking at mitigation options for cyclists and walkers. A train would be a good option as a thought.

Thanks for the comparison to the Tillikum crossing bridge. That gave me some good perspective.

I believe that the height is a social justice issue. I suspect that most of those who read Bike Portland can deal with the grades. They might not like it, but they can deal with it. Those less “physically” fortunate cannot. They cannot afford transit either. If one takes a critical look at those who walk and bike across the bridge, it will be clear that the bridge height being proposed is totally unfair to those who have long been punished by a most unjust transportation system. If social justice was other than a PR effort by the IBR team, the bridge would not be anywhere near the height proposed.

I feel like if you are physically capable of making the 2+ mile trip on foot/bike from destinations in Portland to Vancouver you are capable of climbing 100 feet on a 4 percent grade.

One nitpick – IF I did the math correctly, to gain 178 feet at 4% grade would take “only” about ONE mile, not two. The bridge would be about two miles long, a mile up, a mile back down, unless I’m missing something about the elevations at each end.

Has the idea of bi-directional lanes been considered? Why have lanes that are used only for rush hour one direction?

Regardless, it seems like we should try congestion pricing before determining the design parameters for the the thing:

https://cityobservatory.org/how-to-solve-traffic-congestion-a-miracle-in-louisville/

“Louisville charges a cheap $1 to $2 toll for people driving across the Ohio River on I-65.

After doubling the size of the I-65 bridges from six lanes to 12, tolls slashed traffic by half, from about 130,000 cars per day to fewer than 65,000.

Kentucky and Indiana wasted a billion dollars on highway capacity that people don’t use or value.

If asked to pay for even a fraction of the cost of providing a road, half of all road users say, “No thanks, I’ll go somewhere else” or not take the trip at all.

The fact that highway engineers aren’t celebrating and copying tolling as a proven means to reduce congestion shows they actually don’t give a damn about congestion, but simply want more money to build things.”

With a $2 toll and bidirectional lanes seems like this thing could have much LESS space for cars than the existing two bridges, yet still not have congestion.

Oregon seems intent on wasting Billions of dollars of OUR taxpayer money – it all just seems crazy to me…..

So… why not a tunnel? Seems like it solves a lot of the concerns regarding the infrastructure and views at either end (even gives some real estate back to Portland and the ‘Couve). It provides more flexibility to solving grade issues and keeps the river traffic moving and unencumbered. We could leave the existing bridge (newer span) in place for bikes/peds and Hayden Island access to the OR side. I-5 wouldn’t connect to SR-19 any longer, but SR-500 and 205 are literally right there. A tunnel can also help solve the railway bridge issue.

Construction costs are likely higher than the bridge, but the constant planning failures by ODOT and WADOT aren’t cheap either. They’ve already cost us huge chunk of that price difference. By my count, over $200million so far.

Tunnel gets the job done, IMHO. BP even covered some of this recently: https://bikeportland.org/2022/02/23/the-overlooked-i-5-columbia-crossing-option-an-immersed-tube-tunnel-348880