— By former BikePortland Assistant Editor, Lisa Caballero

I’m in Geneva, Switzerland, on vacation with my husband, but I can’t stop thinking about Portland. That’s because every time I see a nice bike or pedestrian facility, which is constantly, my mind races back to our own efforts to make Portland safer, greener and more livable.

Geneva is a wealthy city, with enviable pedestrian and bicycle infrastructure, and it has already successful transitioned away from car dependence. So it’s exciting to be here, and to be reminded that Portland gets a lot of things right.

On the other hand, I can’t help but bemoan all our plastic wands and paint.

The design elements aren’t so different between the two cities — the protected bike lanes, lane narrowing and road diets — it’s just that Geneva uses permanent materials and makes bolder changes. No half-measures or timidity here. So I’m writing this post as encouragement — you’re on the right track Portland, go for it! But also as a gentle kick in the butt.

Join me if you will, for a photo tour of some first-rate infrastructure. I’m also throwing in a little history too, because Geneva wasn’t always like this. How it went from being a city overrun by cars to where it is today shows that the transition is possible, not easy or cheap, but possible.

Bike lanes

I can’t pass one of these parking-protected facilities without thinking about the Broadway bike lane debacle. Geneva has parking-protected bike lanes all over, other cities do too. So Portland isn’t doing anything unusual or experimental by installing them — parking-protected bike lanes have become standard fare.

And look at how unapologetic Geneva is about reclaiming a whole lane from cars. The width of those cycle tracks in the first photo is generous. Nothing about them reads as temporary or added-on, they are an integral part of the street.

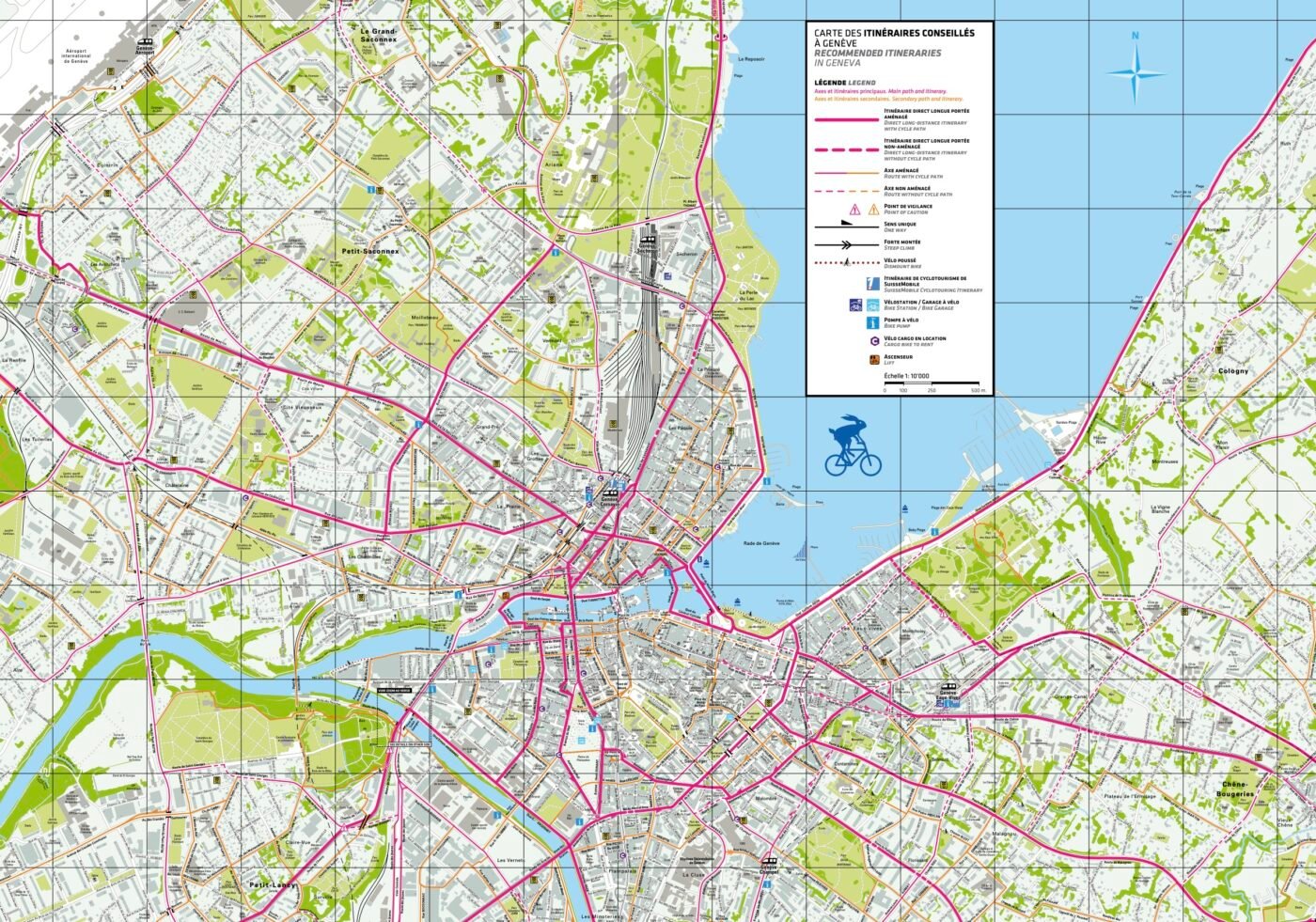

As you can see in the map above, the Geneva area has built a network of cycle tracks (shown as solid pink and orange lines). I don’t know when it dates from, but in 2018 a national initiative passed which required cantons (states) to plan and build connected bike networks, and the Swiss government to build “quality” bike facilities on 500 km of federal roads.

Closing streets

Councilor Mitch Green lit up the BikePortland comments a few weeks ago with talk about closing streets. There are many ways to do that, and Geneva uses most of them. Once you become attuned, you can find repurposed streets and parking lots all over the city.

Europe wasn’t always like Europe: some history

I can hear it from all the way across the ocean: “But Portland isn’t ___.” Fill in the blank [Paris, Milan, Geneva].

I understand that. But what many folks might not realize is that, not so long ago, those European cities were overrun by automobiles. (Remember Art Buchwald? He was mostly before my time too, but he had a joke: “Why are there so many churches in Paris? So you can pray before crossing the street.”)

Corny jokes aside, I took my first trips to Europe with my husband in the 1990s, from Manhattan, and I can tell you that car traffic at that time felt more threatening in Paris and Geneva than in New York City. And things weren’t that great in pre-Bloomberg NYC either.

Geneva tore out its tram network in the 50s and 60s. In the 70s, in the name of urban renewal, it razed entire neighborhoods. It also widened streets to accommodate cars. Europe surely had its own version of Robert Moses.

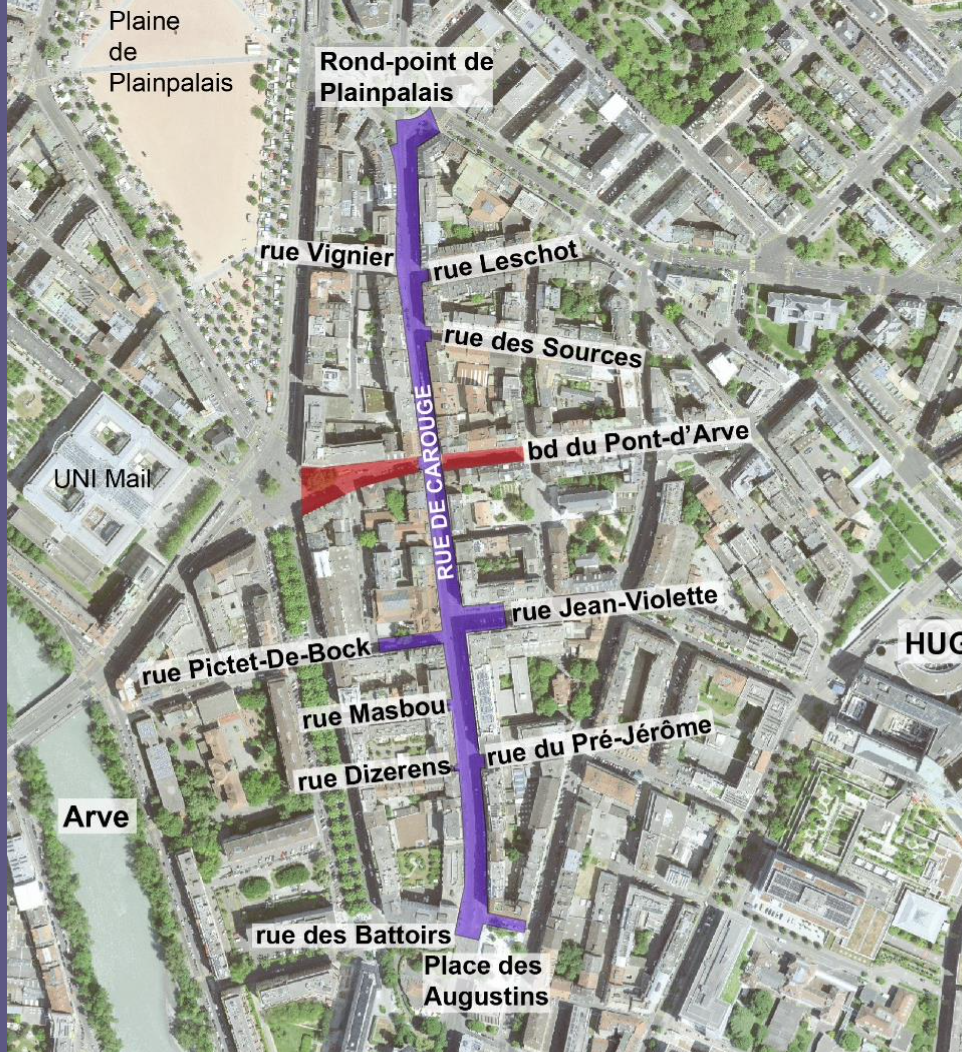

The rue de Carouge

For me, the rue de Carouge represents an inflection point, a specific location where the pursuit of modernity finally came to a halt. You can see it in the photo above.

Notice the inconsistency in building setbacks? The street was slated for widening; in anticipation, the city required bigger setbacks for new buildings (the old buildings were to be torn down).

But the widening never happened. And all that’s left to mark the beginning of what has turned out to be a significant urban design course correction is this jagged line of façades. (There should be a commemorative plaque or something.)

The other cool thing about the rue de Carouge is that it carries the only original tram line that Geneva didn’t tear out. The last one standing. Apparently too many people used it to stop the service.

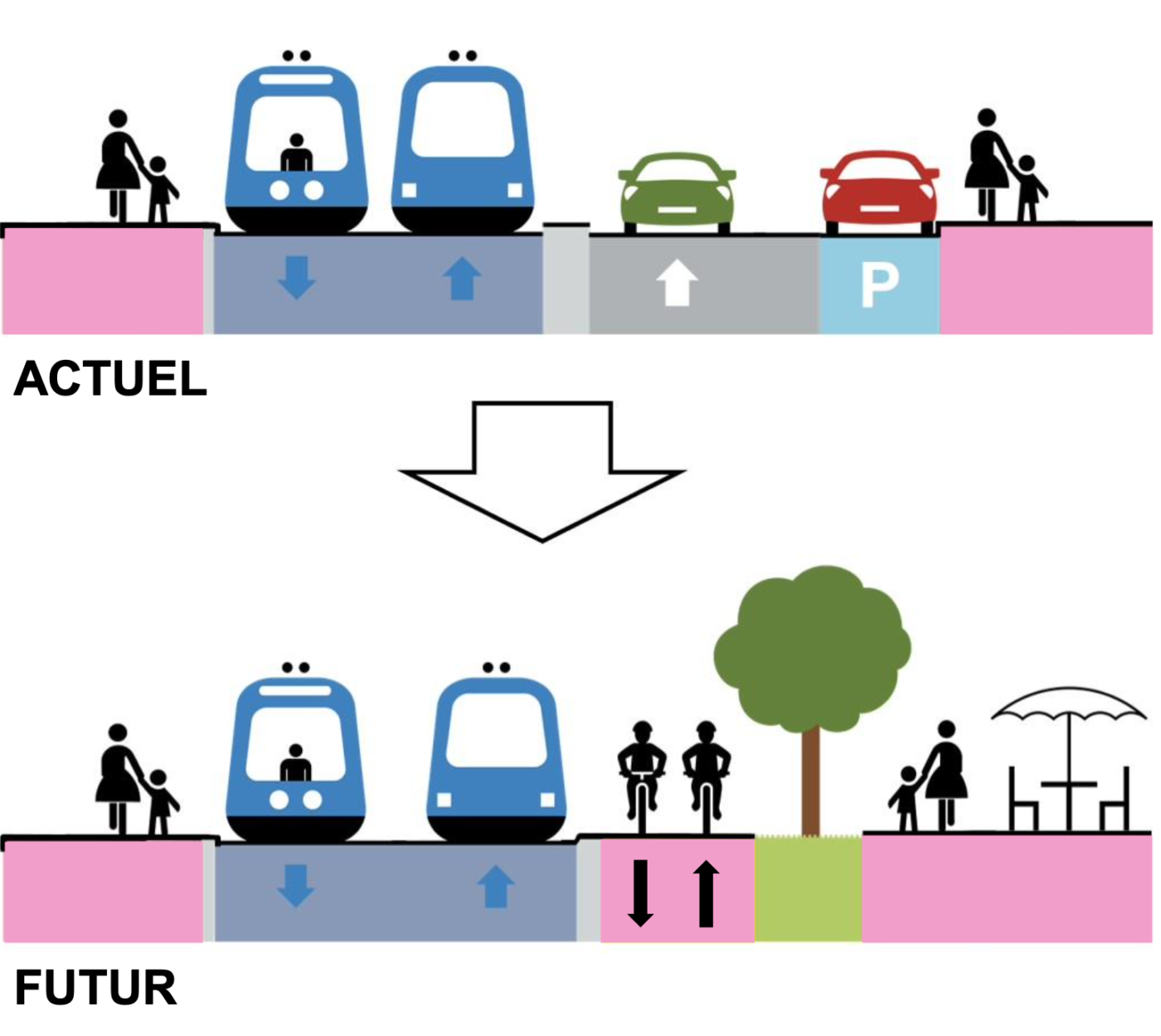

That’s all about to change, though, because Geneva has already broken ground on its big new plans for the street: it’s soon to be the heart of a car-free zone. Here are the current and future street cross sections:

The rue de Carouge is one of the main retail districts through Geneva, comparable to Hawthorne, Division or NW 23rd. Can you imagine if Portland closed a half-mile of those streets to cars?

Why Geneva can get tough on cars

After its last tram deinstallation in 1969, Geneva, at great expense, began building a new tram network in the 1980s. It expanded its trolley-bus network also.

Having a good public transportation system has let the city put policies in place to discourage car use:

- Geneva doesn’t seem to have any free parking.

- The city heavily taxes car ownership with a formula based on vehicle emissions and weight, and with no income accommodation. (A friend of ours who owns an old car pays over $1,000 a year in city tax.)

- Additionally, residents pay around $200 for a blue zone residential parking permit.

- The city has removed a shocking number parking spaces.

Tear down those signals!

As a result, there is a noticeable drop in the number of moving cars through the city. Like in Manhattan, residents who own cars mainly use them for getting out of town on the weekend, not for commuting or errands — so there are many perma-parked cars, and it is difficult to find a parking space.

With so much less car traffic, Geneva has taken the bold step of removing traffic signals at some intersections. It looks chaotic — and maybe it is — but crossing at one of these decommissioned intersections feels pretty comfortable.

I like the intersections where they have removed the signal and replaced it with a painted circle to indicate a round-about. Drivers appear to respect the paint.

Traffic fatalities

I’m not going to look for historical data to try to establish a correlation between reduced number of cars and traffic deaths, but the Geneva area presently has few traffic fatalities. I can’t find statistics for just the city (which has less than a third of the population of Portland anyway) but the Canton of Geneva has about the same population as Portland, so I’ll use the state numbers.

In 2023, the canton saw 13 traffic deaths, nine of them on two wheels: four cyclists, three scooterists; two motorcyclists; one car driver, one passenger, and two pedestrians.

In 2024, it was one cyclist, three motorcyclists, three scooterists, two people in cars, and four pedestrians. Of the pedestrians, two were hit by trams.

Geneva characterizes these numbers as “stable, but high.”

Here’s Portland in 2024 according to BikePortland’s Fatality Tracker: 67 deaths in total, nine motorcyclists, five cyclists, twenty-six pedestrians and twenty-four people in cars.

I’ll let you chew on those numbers yourselves, I‘ve got to wrap this post up. I wouldn’t have been able to write it without my husband, who is from Geneva and knows the city like the back of his hand. I’ve relied on his memory in a couple of places, and fact-checked him where I could. To him, and the friends and family who shared their transportation experiences with me, thank you.

Thanks for reading.

BikePortland has served this community with independent community journalism since 2005. We rely on subscriptions from readers like you to survive. Your financial support is vital in keeping this valuable resource alive and well.

Please subscribe today to strengthen and expand our work.

But Portland isn’t ___.

(Though one thing we do apparently have in common with Geneva is referring to motorized vehicles as “bicycles”.)

“Comparison is the thief of joy”. If we’re not willing to explore the underlying aspects of a society that has things we don’t, why bother comparing at all. Bike advocates will wax on about how nice this all looks and yet financial services and commodities trading is 35% of Geneva’s GDP. They prioritize capitalism as the engine for good services, we can’t keep an outdoor retailer and then wonder why we don’t have separated bike facilities and streets closed for vehicle traffic. They have a Four-Seasons, Ritz-Carlton, Mandarin Oriental, Fairmont and others, our one Ritz Carlton is literally going to go out of business. Wild.

I didnt realize the agreed upon definition of bicycle meant that it can only be human powered with zero assistance from a motor.

I didn’t either. But look at the photo captioned as a bicycle; it shows a motor powered vehicle with zero assistance from a human.

That’s what made the comment seem humorous to me; it wryly illustrates how some in the bicycling community have thoroughly embraced motor vehicles while simultaneously engaging in a war on other motor vehicles. It’s really kind of absurd when you think about it.

“Can you imagine if Portland closed a half-mile of those streets to cars?”

I picture it every day.

Great article! Thanks Lisa!

Taxing cars on age is interesting. I imagine it’s a reasonably good proxy for emissions (rate) and fuel economy. But that does create some perverse incentives where an infrequent driver may feel the “need” to replace a perfectly good “sunk cost” (carbon from manufacture & $$). In an ideal world, we’d find away to tax actual emissions. But finding an economical and socially palatable way to do that well beyond my pay grade.

For gasoline powered cars, this is easy: gas tax.

This doesn’t account for the quality of combustion though. That’s important because uncombusted fuel is arguably worse to emit than CO2. That’s what I was getting at (and probably the biggest difference you see in cars of various ages).

I think gasoline consumption and CO2 emissions are closely enough correlated that for public policy purposes we can just assume they are equal. Especially since we have an established mechanism for taxing gasoline consumption and essentially no way of factoring in “combustion quality”.

I think this is a perfect/enemy of good type of situation.

If you were really concerned with old polluting vehicles on the road, we could reinstate Cash for Clunkers. But probably not until after 2028.

https://www.investopedia.com/terms/c/cash-for-clunkers.asp

Volkswagen TDI scandal is a great case in point. They had real world 45+ mpg fuel economy that could rival most comparable hybrid gas cars. But under heavy loads and hard acceleration, they emitted nitrates and sulfates at excessive levels. A fuel tax doesn’t capture the actual air quality impact.

Similarly, aftermarket diesel emissions tuning can simultaneously improve fuel economy and power of diesel trucks, while massively increasing emissions of regulated particulates. Again, a fuel tax rewards the cheaters.

The real scandal there was not the emissions, but the way VW lied and deceived regulators internationally, even to the point of designing and installing deceptive sensors in their vehicles.

In Oregon, we do test vehicles for emissions to ensure they are within acceptable limits. I imagine some people cheat those in various ways, but I don’t know if there is a practical way to prevent that, or if it’s a big enough problem to even worry about.

Oregon emissions testing is a joke. Emissions aren’t actually tested at all. They just check to see if the car’s engine control unit is reporting that it is operating within normal parameters. It is laughably easy to fool Oregon deq testing. Other states actually test emissions. Oregon does not.

If you have custom vehicle mods and are trying to cheat the system, you’d press the “emissions testing mode” button on the way to the testing station. That’s essentially what VW did.

Is there any evidence that relying on the engine’s computer for data is unreliable in a meaningful way?

There’s a whole genre of YouTube videos that instruct viewers how to easily bypass O2 sensors. If you disable your O2 sensors, you can run straight pipes with no catalytic converter and still pass emissions tests… I don’t know how common that is, but it’s pretty easy to do.

Diesel truck engine mods are a multi million dollar industry, and there were at least a couple of major distributors operating in the Portland area that were targeted for prosecution before the Biden admin decided to deprioritize enforcement of vehicle emissions laws.

If you’ve ever seen a truck roll coal, it was definitely an illegal modification that was producing illegal levels of particulate emissions. I’ve seen dozens and dozens, personally.

I don’t know if anyone has a handle on the scale of the problem, but it’s not insignificant. The EPA probably had a website about it at some point. Doubtful that kind of info is maintained by the government under the current admin.

Here’s a peer reviewed article that says that roadside monitoring is effective at reducing vehicle emissions: https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.abl7575

California, Virginia, Colorado, and other states do mobile enforcement. They also measure actual tailpipe emissions, not OBII scanner readouts, like Oregon.

Oregon only tests in metro Portland/Medford. Want to get rid of your car that can’t pass the test, sell it to someone outside ofmetro Portland/Medford. Oregon is not serious about emissions testing.

The new 2025 automobile tax is more complicated https://www.ge.ch/impot-vehicules/nouvel-impot-2025 (in French): Briefly a 120 CHF ($135) base, then a progressive weight tax for EVs, and a progressive g/km CO2 tax for ICE cars. For old cars owned by lower income friends the price becomes prohibitive.

Thank you, I’ve corrected the text to reflect that.

I feel the same way about giving tax breaks for having children.

Something I don’t understand is the city’s seeming resistance to widespread parking protected bike lanes. There is a lower probability of getting doored (since most people drive alone and exit from the driver side), provides a protective barrier, and doesn’t reduce any parking. Seems like a win-win for everyone, what am I missing?

Reduced visibility increases risk of being hooked, and I don’t like being trapped if something happens in the bike lane ahead (perhaps someone unloads their vehicle into the bike lane, as I’ve seen several times, or sometimes people just hanging out there). Those are my primary complaints about the design.

Hooks are a real risk, while danger from behind, the primary thing protected lanes protect against, is pretty much not.

BTW, the risk of getting doored is probably greater in a parking protected bike lane than in a sufficiently buffered bike lane (exiting passengers probably don’t consider the possibility of a cyclist coming on the curb side of the vehicle). But a modern bike lane should offer a degree of protection from dooring either way.

I think the solution to the risk of hooking is buffers, or constructed islands, at intersections at other conflict points. But that means taking away parking spaces, and I think that, along with the cost of building/striping, is probably the primary driver of door-zone vs. parking-protected bike lanes.

Hi Watts – have you been hooked a bunch?

I ask because I regularly use the parking protected lanes on Broadway and 2nd downtown, and I use the buffered lanes on Vancouver/Williams daily. I would say my dangerous car interactions happen in buffered/unprotected lanes twice or more as much as the parking protected lanes. The worst right hook I’ve gotten was in an unbuffered gutter lane when I had a green light to go straight on NE Lloyd crossing Grand, and a car turning right didn’t have a blinker on and didn’t see me, and we smashed into each other. I slowed down at the last minute when I realize the guy wasn’t going to yield to me, and rode my bike home with some sore shoulders. Very lucky!

That’s my own anecdata, so obviously we have diverging experiences. I’m curious why, do you think?

I ride a regular commuter, and I would put my riding style at medium fast and medium assertiveness. I’ll even treat a few red lights as stop signs if the intersection is clear. You can use that information to compare our riding styles if that’s helpful.

I’ve often gotten the sense that you feel protected lanes slow you down. I find that cars stopped/parked in buffered lanes slow me down daily, where as a slow rider in a protected lane that I have to wait a block to pass slows me down very occasionally.

So, I’m curious: why is your experience with protected lanes so different than mine? Is there any type of protected lane infrastructure that you support and would like to see in Portland? Are there any examples in Lisa’s photos that appeal to you? What road/path in Portland gives you your ideal riding experience?

Super sorry to hear about your crash. Huge bummer, and glad you weren’t (seriously) hurt.

TL;DR: My criticism of protected bike lanes boils down to this: protected lanes protect against a low risk threat (being hit from behind), while increasing a high risk threat (hooks).

The main “slowing down” complaint I’ve levied relates to Seattle, where their signal timing through downtown is infuriating. I don’t really see that as a “protected bike lane” problem, but as a specific implementation issue that happens to impact a protected bike lane.

In Portland, my main concern is the increased potential for hooks because of the reduced visibility and unexpected location of bikes. As you know, hooks are one of the major threats to riding in traffic.

I’ve was nearly hooked on SW 2nd, in the new bike lanes. I strongly prefer 4th where I can safely ride in the center lane like a king (until PBOT screws that up, at least).

I like Better Naito a lot (it’s become my preferred N/S route on the west side), especially with the lack of other users at the times I ride; is that a protected lane? The other standout facility for me is SW Oak, where an entire traffic lane is given over to bikes.

The Hawthorne protected lanes are better than I thought — especially where signals are used to prevent hooks (the unsignalized crossings make me nervous given the speed involved, but I’ve never had an incident). The prior situation there was a bit stressful, and the current situation is less so.

Do you think a protected lane would have prevented your hook?

PS Our riding styles sound similar.

I am 100% positive a protected lane would have prevented the right hook I was involved in. Given the road doesn’t have parking on it, I’m working on the assumption that the protection would be either a curb or wands – both visual cues to drivers to be prepared to interact with bikes. There was a bike signal at the light at the time, but I think that goes to show how easy one indicator is to ignore, but multiple indicators – i.e. lane protection AND signals/islands/etc. – can send a clearer message.

I was thinking about the point you like to make that rear hits are far less common than turning hooks, even without infrastructure. I don’t think a strong concern for a rear hit is irrational, though. To address this legitimate fear, we’ve created bike lanes, which ostensibly keep cars on separate tracks from bikes, preventing rear hits. To me, that means we can use infrastructure to solve the problem of hooks. dw above is on the money with intersection islands, and a few of Lisa’s photos above have good examples. They’re more expensive, but if they can largely solve the problem of hooking, that’s worth it, no?

Lastly, we have another disagreement on which street is more comfortable to ride on! I would choose 2nd over 4th any day! Frankly, riding in the center lane on that or any street sounds like a circle of hell to me. To each their own!

Curb protected lanes like you are describing do not raise the visibility or unexpected position concerns that a parking protected bike lane does, so I have no general concerns about them.

I agree that a fear of being hit from behind is not irrational, just as a fear of snakes is not irrational, even though the chance of being hurt by either of them is pretty small. If we can address that psychological fear without increasing actual danger, then I am all in — my complaint is infrastructure that increases common dangers in order to make rare events even rarer. And, of course, I am totally in favor of reducing hooks through better infrastructure.

My preference would be to keep both 2nd and 4th as they are, so different people can find a street that makes them the most comfortable. I like the center lane because drivers can easily see me, and are not trying to turn in front of me. Since I can ride at the speed of traffic, it feels pretty comfortable.

Hey John, It’s a complicated question, and you’ll get a lot of “I feel” and anecdotes etc from people, who are currently cyclists, but don’t really get the value of a separated network (e.g., the inclusion of non-avid cyclists, people with disabilities, etc).

I’ll link to Cityhikes to give you an idea of how Portland’s planning policy has baked in the essential movement of other modes (SOVs) vs safety of cycling. Blumdrew can explain better, but that policy preference has historically led to a specific focus on politically feasible, and largely ineffective greenways. When designed largely without divertors greenways simply become a means for building “bike infrastructure” without really building any bike infrastructure. So whereas the city theoretically has a hierarchy of ideals consistent with prioritizing pedestrians first, then cyclists and so on, practically speaking Portland builds close to zero separated bike lanes per year, has no plan to build a separated network, and generally precludes any bike infrastructure given SOV traffic counts.

Ironically, my primary complaint is that protected bike lanes cater to the “I feel” folks while increasing the actual danger from things like hooks.

When I talk with traffic engineers here in North Carolina, they remind me that painted “bike lanes” aren’t really for bicyclists, they are for car drivers, to keep them in line – literally. When you build a barrier-protected bike lane or parking-protected bike lane, it is for bicyclists, it takes space away from car drivers and if car drivers “get out of line” they’ll hit other (parked) cars, which from a city government perspective in which most elected officials still drive, means that staff will get blamed for designing a street that allows for bad or distracted drivers to hit other drivers.

Lovely story. I always appreciate some coverage of a foreign city like Geneva with some history of its transportation policies. It shows that just about everywhere has had, or is having, or will have, similar conversations about allocating road space and competing visions for transportation. Many of those infrastructure examples would be possible here in Portland with leadership and vision. Thanks for sharing!

Geneva has just over 200,000 residents (about the size of Eugene or Salem) with a metropolitan population of a bit over 1 million. In other words, it’s got a bit of a problem with urban and suburban sprawl that extends into nearby France (its airport is partly in both countries). And I’m guessing it’s a lot like other Swiss cities that I’ve been to in that local authorities severely under-count the number of foreign-born residents there.

It would be more interesting to me on how the suburban areas are being adjusted and modified (or not) for public transport, bicycling, walking, land use, and so on.

Swiss urban sprawl tends to be more compact than American urban sprawl. Here’s a neighboring municipality to Geneva, Onex, which has a population density of 17k/sq mile (4x of Portland). In Onex, I see a main drag with pretty nice bike lanes and a dedicated tramway.

A lot of the Swiss borderlands have seen massive growth in the last 20 years or so. In Ticino (where I’m most familiar with and have visited a few times), there’s a huge amount of new industrial development that leverages the proximity to Italy for lower wages (but still high wages for Italians commuting into Switzerland). I would assume these dynamics are also at play in the Geneva area, though I am less familiar with the wage arbitrage with France as I am with Italy.

My personal anecdote: suburban Switzerland has public transportation which rivals every major city in the US outside of New York. When I’ve stayed in suburbs of Lugano, there were ~8 to 10 buses an hour heading to downtown for the majority of the day (in an area with population densities of ~6,000/sq mile too). And it’s usually fairly walkable, and definitely by US suburban standards.

Interestingly, the canton of Geneva’s population is 514 K, compared to City of Portland 652 K, with rather similar surfaces (and climate), so both have about 1,800 habitants/km2. And Geneva, similar to Portland, but contrary to Zurich and Basel, ripped out nearly all its streetcars in the sixties, only to rebuild them recently. As to your question, the buses and trams (and a new Leman Express commuter rail) extend into France and to Park & Rides there (the borders are now open between all Shengen countries). The map Lisa included extends beyond the city of Geneva proper and covers some of the neighboring towns and there are decent bike lanes. In my opinion the main difference between these cities is that in Geneva it is possible to get anywhere by public transport (or bike/ebike) and it is expensive and most painful (traffic congestion/scarce parking) to drive.

This is very interesting Robert. Thanks for posting. My guess is Geneva went the way of a lot of French cities in the ~60s, tearing out streetcars in the name of progress, even though Swiss cities tended to maintain theirs. Please correct me if you know.

Basel, Bern, and Zurich were the major Swiss cities to maintain tram (streetcar) networks throughout the entirety of the twentieth century alongside Geneva’s single line. A quick nomenclature note: in Europe, what we would call streetcars are more commonly referred to as trams – helpful for doing further research. Here’s a wiki link on tramways (historic and current) in Switzerland. Lausanne, Luzerne, Geneva, and the Italian speaking cities (which are essentially a conurbation now – Lugano, Locarno, Mendrisio) all had all removed their lines by the 60s. It seems to me that Zurich and Basel were exceptional in their retention of essentially their entire networks, while every other Swiss city either mostly or fully dismantled their tram networks in the middle of the twentieth century.

I can’t really speak further on it – other than the general trend worldwide of favoring cheaper buses and auto-oriented urban planning. I’m sure local politics in each city played a big role in if/when trams were abandoned like you mention though.

Much obliged. That’s some interesting stuff. I wonder if the funicular in Lausanne (and a few others if I’m not mistaken, but may also include cogwheel trains) went into disrepair or it was just too functional to get rid of. I guess it really depended on how solvent the systems were and how much it would have been to upgrade them? I mean we’re also talking about one of the richest countries in the world, particularly circa late 19th/early 20th, so it may have just been more auto age ideals at work. Incidentally, Basel uses a fixed cable line and current to ferry people across the river, which i always found ingenious, and wish we had one here.

I know in Lugano, the funiculars were retained for either extreme functionality (the one connecting the main station to the central city) or for tourism/heritage value (the ones up San Salvatore and Monte Bre were only ever for tourists anyways).

I think it’s important to recall that most US cities sprawled under full-blown and well-funded auto age dreams, while European cities were still rebuilding from the war. By the time the European recovery was mostly finished, the oil crises of the 1970s (which largely ended auto age optimism even in the US) had taken hold. So most European transit systems were more solvent by virtue of having less auto competition in the pre-1970s era, and reinvestment wasn’t nearly as costly. That’s how I think about it anyways. So historical circumstance presents itself as greater solvency for European transit systems, which led to a higher degree of preservation and expansion here than there.

Eawriste, blumdrew has answered really well. I’m also wondering if there is a north/south, Germanic/Latin divide.

I love Switzerland. I felt similar ways about Zurich when I visited last summer as you write here about Geneva. I would live in Zurich if I could speak German and had the money, and I very rarely feel that way about cities that I visit outside of the US.

I think it’s easier to remove car infrastructure when there are reasonable alternatives. We’ve all (presumably) heard of the incredible Swiss trains – and they are truly incredible. But beyond that, the rural bus provider (Post Bus) gets a whopping 175 million rides a year (in per capita terms, it’s almost on par with TriMet [20 vs. 28]). You can get to basically every place in the entirety of Switzerland on a train + bus. So even rural cantons like Graubunden have car ownership rates lower than every US city other than New York.

In Oregon, you can’t even take a bus directly to the largest urban area outside the Willamette Valley (Medford) from anywhere in the Willamette Valley. We are so far away from having a sensible state public transit system, we can hardly be surprised when everyone owns a car.

That’s a good comment, thank you Blumdrew. What is interesting about Geneva as an example, is that it suggests an order in which changes need to unroll, i.e. with a good public transit system it’s easier to get hard-nosed about cars. Portland is having to do a lot at the same time —- densify, build a transit system, build active transportation system. So it is a bumpy transition.

Interestingly, the Swiss recently voted against a plan to widen the freeway between Lausanne and Geneva. As Joe Cortright recently pointed out to the city council T&I committee, dollars spent on freeway widening could fix most of Portland’s surface street problems.

Hey, Lisa. Interesting conversation. Love the article. Hope you got to basel, which is one of my favs. I guess I’m much less prone to believing in any specific “order” for change, but I think I hear what you’re saying as a rule of thumb.

As an example, NYC had–arguably still has–one of the best public transit systems in the world. At the same time (to your point) that cars were infrequently used prior to 1900, it was only natural for the city to build separated cycle tracks (e.g., Ocean Pkwy bike path 1894). It was clear even then that it is safer to have slower-moving people separated from cars. But because of cultural priorities (e.g., as overnight parking was allowed in the city around 1950), those bike paths were torn out or left to degrade and became essentially unusable (but a great place to do bmx jumps).

My point is: the transit system was there, the density was there, the demand was even there (a lot of people wanted to bike), even some basic infrastructure was still there, but cycling and walking was looked at as more an inconvenience for early 20th century city planners. Portland certainly doesn’t have a fantastic transit system, nor have the density of NYC (outside of downtown). But I’m skeptical of the idea that we aren’t “ready” or at the right “stage” for a separated bike network. As you alluded to Joe Cartright’s, it’s cultural priority, not ability. We don’t have a separated network because it’s simply not a priority for the city.

Yeah, it feels it’s all a bit chicken and egg for most urban issues. It’s hard to get people to support removing car access without great public transit, but it’s hard to get great public transit when everyone is so accustomed to using a car. I’m not sure there’s a perfect path forward, but I feel generally more at home advocating for improving transit than I do at limiting car access (even if I support both).

Portland’s transit network is pretty good, but I think the loss of downtown commuter traffic will make things look bad for policy makers for the foreseeable future. For better or worse, the region’s historical push to centralize office jobs in downtown Portland alongside transit investment into it means that no matter how hard we pivot, we will likely never be able to fully recover from the rise in work from home. It’s up to you if that’s good or bad – I waffle on it personally. On the one hand, saving all the time and energy required for commute trips is good, but on the other hand work from home has a generally de-centralizing effect which I just can’t get fully behind – not to mention the price effect on work from home hotspots (Bend, Heber, Truckee, etc.).

Anyways, I think Swiss transportation policy is fascinating. While other European countries have gone all in on high speed rail (usually at the expense of rural connectivity), the Swiss have gone mostly in the opposite direction. There are almost no abandoned lines in Switzerland (~500 km or 10%) compared to France, Germany, or the UK (~30,000km or 50%) and pretty good passenger service exists everywhere on the network and I think this helps create the political situation to reject freeway funding

If that’s even politically/technically/financially possible in a city like Portland.

Mass transit works great for some trips, is ok for more of them, and is awful for many others. It is wasteful to drive big diesel buses around on routes with low ridership or in the middle of the night when there just aren’t many riders. Drivers are expensive. Stopping every few blocks makes transit inherently slow, no matter what else you do to speed things along. Downtown is excruciating. Potential riders now have a hugely negative view of the transit experience.

I do think our general assessment of the situation is similar: we should improve transit where we can, and the hollowing out of downtown creates very challenging challenges in doing that. We both think the Swiss rail system is amazing (but we don’t have that and probably never will).

We may disagree on whether decentralizing is good or bad (I think of it as a neutral thing that’s just a fact to contend with, and see it an opportunity to build more housing downtown, in the hub of our hub-and-spoke transportation system).

Cost of labor is generally higher in Switzerland than it is in the US, and they manage just fine. If we replaced our Military Keynesian status quo with a public transit Keynesian status quo, maybe things would look different (yes I know that’s a borderline silly sentence).

I’ve written about this on my own blog, but most BRT projects in the US consist of what is essentially “minimum viable European local bus service”. The extent to which bus service is bad in the US at almost every level is under appreciated even by transit advocates. But I maintain that’s an implementation issue, not something inherent to public transportation writ large. Wrapped up in this is the idea that public transit is a “carrier of last resort” – something for the poor, destitute, and weird. As long as we continue to treat transit riders as temporarily inconvenienced drivers, we have no chance of shifting the status quo. I remain confident that we can change this status quo, in part because I’ve personally experienced places where riding the bus is normal for everyone (like in the semi-suburban parts of a small Swiss city)

Historically, Portland has done better than most US cities on this front – by centering the job commute and traffic aspects of transit. To some extent, housing in downtown is a good thing for transit ridership, but even if we replaced every job now remote in downtown with a resident, I’d be surprised if ridership rebounded as much as if it would of work from home were ended.

…public transit is a “carrier of last resort” – something for the poor, destitute, and weird.

Is this an assessment of transportation policy or a description of what it looks like? I remember a time not long ago that Portland / TriMet public transit was listed among the top ten cool things about the city. One celebratory phrase I recall is “middle class folks ride the bus.” I was one of them for years, until my usual routes became so overcrowded I couldn’t breathe, which lucky for me occurred at a time my commute cycling capabilities allowed me to bike to and from work in about the same time as the bus. With the increased use of the transit system as an affordable respite from the cold and wet weather by our growing homeless population, the demographic on my usual transit lines changed over the last few years to reflect your “last resort” characteristics.

I imagine a lot of things could be different with a fundamental reorganization of society.

You state that transit’s shortcomings are merely an “implementation issue”. In some cases I’d agree — a tunnel through downtown could improve performance a fair bit (especially if coupled that with stop reduction). In other cases I disagree — there is no real way to “implement away” the need for buses to stop at bus stops, or their inability to connect every pair of origins and destinations. Those limitations are inherent in the transit model.

I’m not sure where you draw the line between “inherent shortcoming” and “implementation flaw”. If it is not possible to improve implementation given the available resources, it in a sense becomes inherent, and at that level, I’m not sure if it matters (and if it doesn’t matter, there’s no point in debating where the line is).

I too have experienced places where transit works well*. Does that mean that, with our geography, development pattern, social/cultural structure, and funding limitations, we have the capacity to achieve the same?

*Though in every place I’ve spent enough time, I’ve found plenty of trips for which transit did not work well, something that can be hard to gauge on a short trip.

“not so long ago, those European cities were overrun by automobiles” yes but for MOST OF HISTORY those cities had no automobiles. Often when motor vehicles are honking and getting worked up because they can’t get through the “narrow” streets of my neighborhood (narrow only because motor vehicles are parked on both sides of the street, plus delivery vehicles double parked), I think, “there were bicycles on this street before there were motor vehicles.” Motor vehicles haven’t been the “normal” or the “default” or the “first” in most cities. It’s just come to feel that way because of one deluded century.

Lisa THANKs for sharing your travel insights!

And as for “The design elements aren’t so different between the two cities — the protected bike lanes, lane narrowing and road diets — it’s just that Geneva uses permanent materials …”

It would be a great PSU TREC student research to do a ROI / Lifespan Analysis on how plastic (temp) vs concrete (long term) bikeway interventions pencil out over time.

[Back when we – city of vancouver – were piloting the early trials of speed cushions in the US (~2000), we found that our rubber units cost way more to install and then maintain than good old fashioned asphalt. Full speed ahead for asphalt or concrete…once we were allowed to use “real” street materials.]

Why does Portland rely on plastic wands and paint? That’s easy:

So they can rip it out quickly! It’s really to maintain the auto-dependent status quo.