(Photos: Timur Ender)

BikePortland subscriber Timur Ender recently visited family in Turkey and shares his impressions about how people get around.

My first memories of Izmir were when I was a young kid so it has been a joy to see it grow in a positive direction over the last 25 years.

Izmir is the third largest city in Turkey and has a population of 3 million people. It is a major port and hub for commerce and a center for higher education, agriculture, and manufacturing. Given its location and weather, Izmir is known for its quality of life and tourism, attracting direct flights from northern Europe to its sunny beaches.

For me, Izmir has a much more personal connection. It’s where my family lives and where I have spent a significant amount of time over the years. It’s a place I’ve watched with admiration as the city has grown and changed over the last two decades. Given how impressive I found the multimodal improvements during my most recent visit this summer, I thought I’d share some pictures about what Izmir is doing to improve transportation options and quality of life in a quickly growing region.

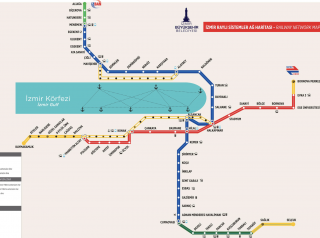

Izmir is a city clustered around a bay with development occurring up toward the hills and along the bay in every direction. Not surprisingly, most transportation investments have been clustered around the bay. The thought being that if you can get near the water (with bus service), you can access regional transportation options like streetcar, light rail, protected bike lanes, ferries, busses, and bike share.

Below are descriptions of recent improvements by transportation mode in no particular order.

Ferries as a transportation demand management (TDM) strategy

Ferries offer a shortcut from one part of the bay to the other. Some transport cars while others are bike/ped only. The frequency and speed of these ferries makes them competitive to driving. It seems the Izmir government has embraced the potential of ferries as a TDM strategy and is prioritizing the procurement of even more bike/ped only boats, providing greater frequency, and adding service hours between 12 a.m. – 3 a.m.

Biking and the benefits of being the first Turkish city to have a bike master plan

There has been a strong advocacy push over the past two decades to connect the bay by bike. With the election of political leaders supportive of this goal as well as funding to make it happen, it appears this has finally become a reality. The bikes lanes are blue and bi-directional. The standard width is six feet (yes, for bi-directional lanes). Another interesting fact is that the jurisdiction providing the funding is prominently displayed on the bike paths, in this case the provincial government. Izmir also has a bike share system with strategic station siting. It is called “our bikeshare” and its slogan is, “now the streets belong to us”.

Izmir’s success in bicycling is due in part to a comprehensive plan, not just for biking but for active transportation generally. This can be seen in how bus fare payment is integrated across multiple transportation modes and municipal parking and cultural facilities. And it can also be seen in how well biking is integrated with other modes, which is probably the greatest win for people riding bikes. The highest quality bike infrastructure exists around ferry stations, new busses feature bike racks, and the bay is connected by bike. All of these discrete but intentionally planned efforts have made it easier for residents to combine modes and conveniently bike from one part of the region to the other. In a part of the world that lacks a reputation for planning, Izmir has shown the possibilities of a connected and integrated active transportation system.

“Dolmus” = Private operators supplementing public transit.

Dolmus is a turkish word meaning “full”. Although there is a rough timetable, these busses generally leave the station when they are full, hence the name. It’s a system of a fixed route, frequent service, green-colored buses connecting people to high capacity transit. Dolmus are operated by private actors in the public transportation arena and are regulated by the government. They require permit approval from the municipality and police traffic division to ensure there is sufficient demand for the route proposed by the private operator and that the route proposed is safe.

Regional rail reducing crosstown commute times.

Izmir has an impressive rail system. It connects outlying areas with the region’s commercial centers. Moreover, most towns and the airport are all on the same rail line. We took a long-distance train from Izmir to Eskisehir and eventually Istanbul. Interestingly there weren’t any at-grade rail crossings until we left the Izmir region which seemed pretty impressive for a densely populated area. Also of note was that long distance rail uses the same exact tracks as regional light rail until it leaves the metro area (with regional rail having priority over long distance). The regional rail system is heavily used and connects people from all parts of the region. Similar to the ferry, given the congestion for cars, taking rail is competitive to driving in the urban core.

Advertisement

A new streetcar line invites more people to walk

The modern Streetcar is about four years old in Izmir; the first modern streetcar systems in Turkey were launched about 20 years ago. The route is located along bustling streets, dense housing, and for portions, along the bay. The stops feature accessible at grade crossings and modern designs. The streetcar runs on dedicated tracks supplemented with bollards to keep cars out which ensures it never gets stuck in car traffic. The streetcars themselves are clean, visually appealing, and spacious. The service is not all that frequent for what one would expect in a high-density area (it comes about every 12 min or so). The low frequency does have the side effect of promoting walking. Anecdotally, my aunt described how she would get to the station, see that the train is 7 min away and decide to walk instead. And while the frequency currently is relatively low, the trains are highly utilized given the proximity to dense housing.

Giant steps toward a walkable city

There were many examples of walking-friendly street design. In Yeni Foca (at right), a beach 45 minutes outside downtown (but still within Izmir province), has changed its main street from two general traffic lanes to a carfree promenade. When I was young, my brothers and I spent our summers here. At night the street would be closed to cars to accommodate the intense amount of people strolling along the waterfront. After dinner, entire families would go on a walk to get ice cream, take in the cool ocean breeze and see neighbors. Today, the permanent waterfront street design features an accessible sidewalk, a blue protected bike lane, and one lane for freight access (garbage service and emergency vehicles only). Our family friends living nearby let their kids roam freely between the beach and their house, seemingly unwilling to find any distinction between a park and the street in front of their house.

Back in downtown Izmir, pedestrian streets begin where the ferry and streetcar lines end. My mom has dubbed this part of Karsayka, the “culinary corridor” due to its flavorful selection of delicious food. Moreover, the main walking corridor had carfree streets intersecting it which made for an attractive pedestrian district full of vibrant storefronts. The opposite end of the culinary corridor is anchored by regional light rail and dolmus shuttles ready to take you in any direction.

Another walking friendly street design I came across was the raised crosswalk. This was a speed bump, accessible crosswalk, and pedestrian safety treatment all in one. The raised asphalt makes people walking more visible and negates the need for an expensive curb ramp. This allows people crossing the street to remain at sidewalk level.

Slow cities as the original Vision Zero?

Seferihisar is one of the many beautiful small towns in the Izmir province. It encompasses architectural sites, side-of-the-road farm stands, and colorful storefronts. Seferihisar was the first city in Turkey to be named a “slow city”, a fact locals were happy to mention but something I was not familiar with. The Cittaslow movement began in Italy and originated from the slow food movement. In Seferihisar, they have used it as an opportunity to promote slow driving and traffic safety as part of their slow city initiative.

The sweet taste of Izmir’s mode share pie

What do all these plans, investments, and policies add up to? For starters, Izmir residents enjoy a wide range of mobility options. These benefits exhibit themselves in better air quality, healthier population, and improved mental health as people enjoy convenient access to human connections, cultural institutions, town centers.

So how does Izmir’s mode share actually shake out? According to the provincial government, it looks like this:

— 24% by private car

— 11% by shuttle (this generally means a bus operated by a private entity to bring people to places like grade schools, colleges, companies, and shopping centers).

— 28% public transportation (this includes dolmus, ferries, rail, and bus).

— 37% carfree (this includes walking and biking; though the vast majority is walking).

Overall, I was impressed with the effort, objectives, and outcomes related to multimodal mobility in Izmir. My first memories of Izmir were when I was a young kid so it has been a joy to see it grow in a positive direction over the last 25 years. The groundwork laid years ago and being implemented today is already improving the quality of life and access to opportunity for Izmir residents and is setting up the region to become a national and international example of best practices for mobility and urban planning.

Timur Ender is an advocate for equitable and livable cities and is on the board of the nonprofit Oregon Walks.

Thanks for reading.

BikePortland has served this community with independent community journalism since 2005. We rely on subscriptions from readers like you to survive. Your financial support is vital in keeping this valuable resource alive and well.

Please subscribe today to strengthen and expand our work.

Thanks for the write-up! I got to visit Izmir for 8 days in 2006 with a friend I met in Italy who grew up there. Really cool city, and the beaches were amazing! Even then, I liked how walkable parts of the city were. A couple of the days, we parked somewhere in the morning and didn’t need to get the car again until heading back to her family’s home again that night.

And I can’t remember if it was Izmir or one of the other cities we visited while there, but I remember there being some public transit vehicles that were a bit like a bus/taxi combo. It was a small bus where you could get on/get dropped off pretty much anywhere along the route, you didn’t have to wait for a specific stop. It seemed like a great idea – was really convenient, and pretty cheap to ride if I’m remembering correctly.

Ryan- you’re right! I’m not sure if this is what you were mentioning but there is a mode of transportation called taxi dolmus. This is half taxi, half dolmus. Similar to taxis, they are 5 passenger cars. Similar to dolmus, they run a fixed route and are cheaper than taxi. Think of it as splitting a taxi ride with someone headed in the same direction (which is prominently displayed on the taxi dolmus. Taxi dolmus serves a specific niche not filled by dolmus and is one solution to the last mile challenge. It is a unique concept for sure but one that has proven itself useful in the Izmir context. Thanks for mentioning that.

Thanks for confirming that! Wasn’t sure if I was remembering correctly 🙂

Great post! Besides the pull of having good non-car options, what are the pushes away from driving? Expensive parking? Cost of having a car?

Turks have no choice but to minimize the use of automobiles and energy in general. Turkey only produces a very small portion of the oil and gas it needs to meet its current needs. The rest must be purchased and imported. Unlike the U.S., Europe or Japan ,Turkey is not a credit creator. It can not just print money to purchase imports with, nor can it run a negative balance of trade. This means each dollar spent on imported oil must be matched with a dollar of exported goods from Turkey. This is the situation more and more of the world will find itself in not far in the future, and the result will be a significant and ongoing increase in personal automobile use everywhere. But as we can see from this report, that is not all a bad thing.

My bad ,I ment to write significant and ongoing decrease in personal auto use not increase.

Great article, it gave me some hope for Portland. Thanks Jonathan for supporting all the different voices!

Portland probably isn’t getting a new flagship commuter option on the scale of the Max. The great hope for Max is to solve the Steel Bridge problem, at once a bottle neck and the thing most likely to fail or need arduous repairs that reduce capacity. We need a maximum effort locally to keep a regional asset working. Also: that bridge is horribly laid out for passage of freight trains. Q: Why are there long slow train passages on the E side? A: Small radius curves on the approaches to the Steel Bridge. It’s our Achilles heel and it’s gonna get us.

More on my wish list: close 2 Max stations, one downtown and one E side, so Max is more like a train. I’m sure people think they’ve done a lot to promote walking within half a mile of the train. It’s not enough, ok? Do more!

An E side flyover bridge over the railroad tracks would lead people walking and biking to the Morrison Bridge. Who would pick a walking route that gets shut down by random waits at the tracks being jarred by the warning bells? At least put a bathroom there, a shelter, newsstand, café cart? Make it a place, not a pit. Find out where the trickle of walkers are now and encourage them!

Another thing: we need faster bus service out to “the numbers” on the East side. Besides dedicated bus lanes which seem so very hard to get, we need to expedite the buses in every way possible. Maybe that’s fewer stops? I know there’s a number for how far apart stops should be, but would people walk a little more for a sexy bus that runs fast and often? I think they would. Make the stops more interesting and put up more shelters! Find a way to make bathrooms available at major stops and points where people change lines. I’m fortunate not to have much of a problem myself, but I know that bathroom access is a serious issue for some people who might otherwise use transit.

I could go on but you’ve already quit reading. It seems to me that Trimet thinks they’re in the bus and train business but they are really in the people business.

Is there enough of Izmir’s “sweet mode share pie” for Portland to try a slice? It sounds way better than what we’ve been eating!

note these small streets and huge increase in density over Portland in the photos. The same kind of density that even readers of this blog sometimes cry about. If you want walkability u nee density. well Portland itself in some portlanders may think Portland is dense it is not.

Heck just opening up those giant houses 2 multifamily would be amazing.

Density is more complicated than your characterization suggests.

While density provides lots of micro-local benefits we recognize here and might group under livability, the larger context within which density occurs (economic growth, population growth, building expansion) is decidedly anathema to livability, quality of life, carrying capacity, a stable climate, etc.

Although people here love to celebrate the idea of density in their census tract, the practical results of greater density at all other scales do not help us advance toward the larger goals, but enable and accommodate patterns that undermine them.

Density is a ratio not a cap.

Maybe tax policy is a way to get at this density thing. Make long-term in-home rentals tax free.