Last week BikePortland wrote about the Homestead neighborhood’s struggle to get a sidewalk built on the frontage of a new 43-unit apartment building under construction on SW Gibbs Street near OHSU. Neighborhood advocates were surprised to discover that the City of Portland does not count pedestrians and cyclists when determining the traffic impacts of developments which trigger a Land Use review.

This situation is interesting in that the developer is working cooperatively with the neighborhood association, and was willing to build a sidewalk, but could not get the permission from the Portland Bureau of Transportation (PBOT). This brings up a larger issue about how Portland will ever build the sidewalks (or bikeways for that matter) we need in this and other parts of town.

This case on Gibbs is such an important illustration of a problem that we felt it deserved a closer look. So take your blood pressure pill and get ready for some wonkery as this article dives deeper into what happens when the city only counts car traffic.

This loophole calls into question how sidewalks and bike routes will ever be built in the areas of town that don’t already have them, like in southwest and east Portland.

Background

First a little wonky background about getting permission to build. Zoning changes, land divisions and new buildings which will increase the density of people living in an area require a Traffic Impact Study (TIS). It is provided and paid for by the developer, who contracts the work out to a traffic engineering consultant. (Keep in mind the consultant’s compensation is not independent of the developer, so there is a possible incentive for the engineer to present information in a way that is favorable to the person paying them.)

The next step in the process is that PBOT reviews and signs off on the consultant’s transportation study, and delivers its report to the Bureau of Development Services, which collects reviews from up to seven bureaus as part of the building permit application process. The review and sign-off are the responsibility of PBOT’s Development Review section.

The Gibbs case

Let’s take a peek at the Gibbs case specifically. The analyses of car traffic for the TIS are most certainly correct, but when it comes to walking and biking, the errors of omission in the overall report are — well, grab that pill.

The consultant applied standard Trip Generation formulas to determine how many more cars would be on the roads due to the 43 new units. The impact of the additional cars is measured by how much longer drivers will have to wait at nearby intersections.

Specifically, impact is defined by administrative rule TRN-10.27, which states that the added cars from a new development shouldn’t degrade the Level of Service (LOS) at nearby signalized or stop-controlled intersections below LOS “D” and “E,” respectively. Roughly, that means that a driver should not have to wait longer than a minute at an intersection. If a new development adds enough cars to the road to degrade service to unacceptable levels, then the city requires the developer to mitigate the impact.

The Gibbs TIS concluded that the additional car trips generated by the new building wouldn’t push the LOS at nearby intersections below the D and E level. Development Review concurred:

. . . the applicant submitted a Transportation Impact Study (TIS), professionally prepared by ———, to support the transportation-related approval criteria, in which PBOT reviewed and agreed with the conclusions that the transportation-related approval criteria are satisfied.

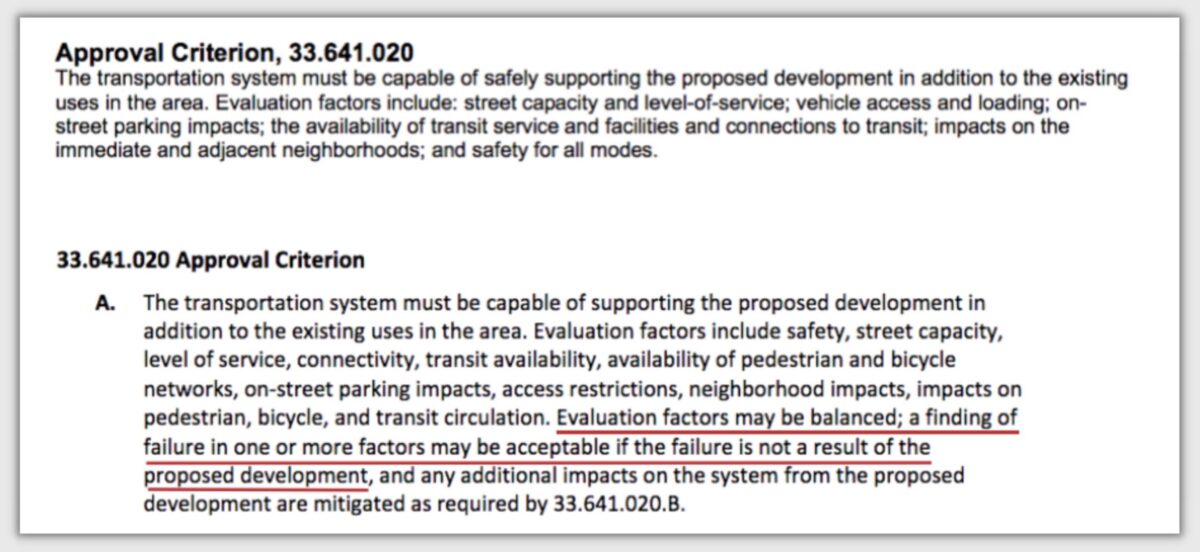

Beyond the TIS, however, the developer must also show that the area transportation system is “capable of supporting the proposed development in addition to the existing uses in the area,” (Section 33.641.020 of city code) Although that section of code lists evaluation factors which do include impacts to pedestrian and cyclists, it was modified in 2018 to introduce a giant loophole:

See the loophole? (It’s underlined in red.) Basically, if the area doesn’t already have bike and pedestrian facilities, it’s not the fault of the new guy on the block, and he is allowed to fail along with everyone else.

The inconsistency is that Portland city code Title 17.28.020 states that developers are responsible for “constructing, reconstructing, maintaining and repairing the sidewalks, curbs, driveways” on the streets that abut their property. But the new, “balanced” wording of Title 33.641.010 lets property owners off the hook. This new wording calls into question how sidewalks and bike routes will ever be built in the areas of town that don’t already have them, like in southwest and east Portland.

This absence of specific requirements for pedestrian and bike facilities leads to motivated reasoning in the resulting transportation system analysis. I’ll pick one of several possible examples from the Gibbs transportation report:

Sidewalks are partially complete along nearby area roadways. When sidewalks are not available along local streets, roadways speeds (posted and statutory speeds of 20 mph to 25 mph) and traffic volumes are generally lower, allowing pedestrians the ability to safely and comfortably walk along roadway shoulders when necessary.

In truth, 2018 and 2014 PBOT traffic counts on SW Marquam Hill Rd (just uphill from the development) reported traffic volumes between 3,000 and 4,000 vehicles per day, with 87% of the downhill vehicles traveling above the posted speed of 25 mph, and the 85th percentile traveling at 33 mph.

The full case file presented to the Hearings Officer shows that Ed Fischer, the president of the Homestead Neighborhood Association, contacted a PBOT planner who works outside of the Development Review section. The planner told him that “this is definitely in the range of traffic where we’d like to see a separated walkway to support pedestrian travel.”

Moreover, this street segment has been identified as needing a sidewalk by PedPDX, the citywide pedestrian master plan. It is also Southwest in Motion project BP-07 and Transportation System Plan project 90049.2. In other words, at least two different groups of transportation professionals have recognized the need for active transportation infrastructure at this location.

None of that—the existing traffic counts and speeds, the project lists—made it into the Gibbs Transportation Report (although neighbors brought some of this up, so that information is part of the record).

Nevertheless, the PBOT review concluded that

Therefore, based on the evidence included in the record, the applicant has demonstrated to PBOT’s satisfaction that the transportation system is capable of supporting the proposed use in addition to the existing uses in the area

What it all means

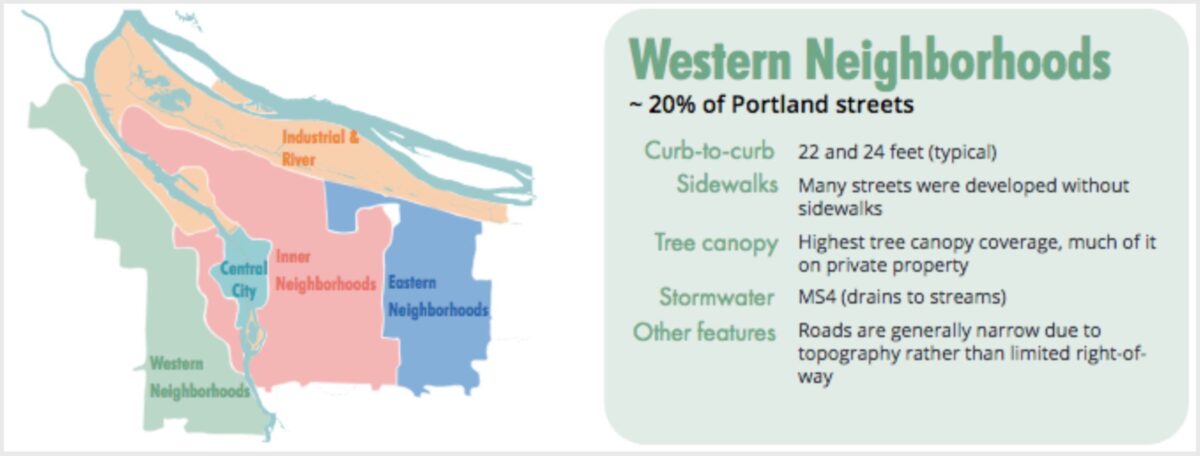

Southwest has the least sidewalk coverage of any area in Portland, and also the highest percentage of uncompleted bike network. Although PBOT has not openly stated it, the de facto sidewalk requirement for new development in southwest appears to have become a six-foot wide gravel shoulder at-grade with the roadway.

There are reasons why this is so. As the Streets 2035 plan points out, the southwest has the narrowest roads in the city, and also lacks formal stormwater facilities (the Big Pipe does not serve southwest past downtown). Sidewalks need to drain their stormwater runoff into a pipe, holding tank or treatment facility, and those are not available in most of southwest Portland.

It would be helpful, and serve to avoid a lot of conflict, and probably speed up the building permit process, if the City of Portland would clearly and proactively state how it plans to safely accommodate people on foot and on bike in the southwest region and other areas of town which currently lack critical transportation infrastructure.

Next week: BikePortland talks to Commissioner Carmen Rubio’s office about the work they are doing to streamline the building permit process.

Thanks for reading.

BikePortland has served this community with independent community journalism since 2005. We rely on subscriptions from readers like you to survive. Your financial support is vital in keeping this valuable resource alive and well.

Please subscribe today to strengthen and expand our work.

SW Portland is all (well mostly) white people so PBOT doesn’t really care about sidewalks there. It’s not part of their “anti-racist” program.

Considering the only place PBOT has truly cared about for the last decade — inner SE — is also mostly well-off white people, this is an absurd argument.

In case you hadn’t noticed, all of Portland is mostly white people.

A great explanation of a deeply frustrating situation. Thank you, Lisa.

With the support of both the neighborhood and the developer, it seems like this is a situation that deserves reconsideration by PBOT. There are likely to be very few opportunities to do such a sidewalk project on this street again and you’d hate to see the City miss such a cost-effective moment in time. This current decision seems like using code to blind oneself from common sense.

Great write-up Lisa, very concise and readable.

One of the other big players in all of this are the banks that loan money to developers – they tend to be even more “car-centric” than the developers.

I once attended a public meeting where a downtown developer affiliated with the PBA said he wouldn’t be able to get a loan from the bank for his project if it had to include bike parking. What a bunch of BS! ‘Sidewalks, bike parking, who needs them?’ is not a good look for either the developer, the financial institution funding the project, or the City Bureau of Development Services.

Lisa, really enjoyed the article. Not so much the outcome. Question for you: why not name the consulting firm? Surely they are adults and can handle criticism or questions!? I don’t understand the protection your journalism has provided them.

Thank you for enjoying the article, Let’s Active. I left out a bunch of names I could have included, but it is all public record, including the reports, and can be found in the long case file I linked to.

I’m not so much protecting people as trying to tell a complicated story clearly. That means I drop details that could distract from my main points. The point of the story is that the system is inefficient and counter to Portland ped and bike policy.

The individuals in the story are pretty much just playing their roles (although I think Dev Rev doesn’t think creatively or use the planning resources within PBOT. There seems to be a long-standing, industry-wide tension between engineers and planners.)

Among planners and planner-wannabes, AICP stands for American Institute of Certified Planners – you often see it at the end of professional planners’ names. Among many engineers, architects, and the more cynical variety of planners, AICP stands for Any Idiot Can Plan.

Thanks for the explanation, Lisa. I might have been reading too much into it.

Some of the planners at PBOT and BDS (they talk to each other about new developments) are die hard free-marketeers. From their perspective, any fee levied against developers will kill the housing market.

Careful of how you use the word “planner.” “Planning” is a separate office within PBOT. BDS and the Development Review office of PBOT are more engineering concerns.

Typically, developers fund and build sidewalks in the public right of way. Why can’t the developer build the sidewalk on private property adjacent to the right of way? Would the city have any control over that? I don’t think it changes the property owner’s liability in any way, since they are already liable for injuries that occur on a sidewalk in the public right of way adjacent to their property.

It’s not necisarrily a liability issue and some cities do this, mostly in high-density downtown conditions. The much more significant issue is continuity. Unless you expect most of the lots on a street to redevelop you’re going to end up with a mediocre sidewalk that jogs in and out and stops altogether in places.

There is a big grade difference- the property slopes down abruptly from the right-of way.

Folks who knows concrete and drainage better than myself: if the sidewalks were built with previous materials (pavers or previous pavement) would that mitigate the storm water concerns without the need to drain into a dedicated storm water pipe?

If you create more than 500 sq. ft of new impervious cover, runoff has to be dealt with: into a (usually new) pipe, or a retention pond (hard to do in SW terrain and soils). Both are expensive, which is why developers protest things that need them. In the Gibbs case, impervious cover isn’t the issue – they are already requiring the shoulder be paved, just not separated fom the roadway in any way. So they are accomodating extra stormwater already.

The builder’s request to narrow the shoulder to 2′? It was to enable a sidewalk to go BEHIND the guardrail. I think a slope and a parking lot would preclude putting one elsewhere on the property.

Anyways, the gist of the argument is that DevReview is denying that there is ANY pedestrian infrastructire to connect to past the proprty, therefore they refuse to allow the sidewalk. Allowing it would acknowledge SWIM, PedPDX and the TSP in this area and others as valid AND needing completion; whether due to budget concerns or personal or institutional hostility, that can’t be conceded.

There are sidewalks on both sides of Gibbs two blocks west. So we can never build sidewalks unless we’re physically adding directly on to them? But we also can only require them when the building is built. So I guess we wait until the property adjacent to end of sidewalk is developed, and then the next property, etc. Must be in order, apparently.

So “developers are responsible for ‘constructing … sidewalks, curbs, driveways’ on the streets that abut their property” when development happens per city code. And the Ped Bike Bill requires the city (or whoever is the roadway authority) to build ped and bike facilities whenever streets are constructed or reconstructed. And the ADA requires the roadway authority to build accessible ped facilities wherever there are routes that non-disabled peds use. You would think we would have a complete network by now.

It’s called Nollan/Dolan; there are lawyers whose entire careers are built upon screeching wildly whenever a development is required to build anything not directly of profit to the developer, and a supine city that offers no pushback whatsoever – in fact, I say it goes out of its way to aid developers in avoiding these costs, they are so afraid of being sued.

Note to Portland: it is better to be sued for something you HAVE done than something you HAVEN’T. see ADA suit…

It almost sounds like you are saying that city bureau staffers function as shills for developers???

If true, this may explain why so many staffers end up on the payroll of consultancies or think tanks with a pro-development/deregulation bias.

AFAIK Nollan, Dolan and Koonce would allow a requirement if the new project generates more trips than before, such as is the case here, apparently.

Thanks Lisa for this in-depth reporting. It goes a long way to explain why the city is so dysfunctional regarding plan implementation. The plans are beautiful aspirational poetry about our future, and the code is locked in a 1950s time-warp of an auto-centric/Robert Moses vision of the future. While correcting the city’s standard operating procedure is multifaceted, three issues come to mind:

I struggle to understand why even simple stuff like this continues to be so difficult.

Tightening rules so that developers have to build sidewalks in front of new buildings is not going to get us a meaningful active transportation network. And leaning too hard on developers to solve an infrastructure issue is going to further discourage new housing construction. If it’s a citywide system it needs to be planned and paid for at a citywide level. We don’t hope that adjacent homeowners will do a decent job of maintaining their 50 foot section of street so it’s safe for cars, so why should we treat sidewalks that way?

Adam, it’s just not the way Portland has been built. The sidewalk policy goes way back. If the city is not going to enforce it, fine, but then they need to come up with another way of allowing people to step off their property without getting hit by a car.

https://bikeportland.org/2021/08/12/sidewalks-and-portland-its-not-so-simple-336493

Bless your heart. Keep stirring the pot! Could you give PBOT a chance to comment on the next one?

Thanks X! Commissioner Rubio’s office gave me a half hour last week, and I will have an article out next week about their efforts to make the permit process more efficient.

When I contacted PBOT for my original Gibbs article (the first of three) the spokesperson gave me a generic SW sidewalk answer, it’s in that article.

PBOT employees are not permitted to speak directly to the press, but I did speak to the relevant folks before I started writing for BP, a few years ago, so I know their answers. (I’ve had good long conversations with the head of development review.)

I think it is more of a high level political/leadership problem, involving city attorney. I don’t have a solution, I can just see that what we are doing now isn’t working.

I don’t understand how the city can not even let the developer build the sidewalk. Are they concerned with impervious area? Seems like there’s plenty of room, in the ROW, between the property line and the roadway. This is two blocks from the continuous sidewalk on SW Gibbs (both sides!) to the west. And a block away, on SW 12th, and up two houses, a huge building project is putting in hundreds of feet of sidewalk, with a planting area and curb. Has someone at PBOT decided that “the sidewalks stop at 12th, and then it’s a rural area”?

Developer wanted to move guardrail to put the sidewalk behind it, narrowing the road shoulder to 2′ to do so. PBOT replied “The appropriate location of the necessary guardrail is identified under the AASHTO/Policy on Geometric Design of Highways and Streets. These standards cannot be modified by the Committee.” I’m not an engineer, but a statement like this: ““Typically, guardrail is installed in the shoulder 2 feet from the slope break hinge point” https://kp.uky.edu/knowledge-portal/articles/guardrail-version-2-3/ shows that the main concern is placing guardrails too close to a slope, which reduces their ability to withstand a crash. It doesn’t say anything about having space behind them (tho they don’t like curbs with them, so maybe no raised sidewalks).

I also saw nothing here https://flh.fhwa.dot.gov/resources/standard/Std617a.pdf giving a hard rule on placement. None of those drawings give specs for lateral placement beyond what to do if you need to be close to a slope. They COULD place the guardrail at the fogline and have the 6′ paved shoulder be protected, They have chosen not to. They did it on SW Broadway Dr with Jersey Barriers, so when they put their minds to it, it CAN be done.

Easier to say no, I guess.

Lisa, this is great reporting on a deeply policy oriented and technical topic!

I appreciate your saying that, Chris.

I second, Chris’ comment. This is a terrific piece that highlights a topic that gets short shrift here: PBOT’s institutional barriers to active transportation improvements. One also wonders how often this happens in other locations without this kind of incisive coverage.

It’s great to see the continued coverage on this.

Obviously, it’s unfortunate that PBOT didn’t conclude that sidewalks should have been built. HOWEVER, I’m not convinced that PBOT’s decision was supported by the relevant codes. I’m not saying that because I’ve read the whole case (I haven’t) but because I’ve seen dozens of times where City staff has made poor rulings that weren’t supported by codes. The obvious evidence for that are the many cases I’ve seen where hearings officers have ruled against City staff and staff reports–sometimes by savagely thrashing the staff decision on multiple points.

For that matter, I’ve also been involved in many cases where hearings officers were wrong. I’ve been scolded harshly by hearings officers and other reviewers in land use cases for bringing up irrelevant issues, only to win appeals because appeal reviewers agreed I and people on my side were right for those exact “irrelevant” reasons. That’s why we have appeals.

The key to me is that if common sense says a decision seems weird–in this case allowing a large development without sidewalks where it’s not safe to walk–it often IS wrong. People say poor outcomes in cases like this are due to codes being written badly. But it’s often the opposite–the codes support good decisions IF you read them correctly.

Two examples of specifics that make me suspicious about the decision:

First, the report mentions factors existing “allowing pedestrians the ability to safety and comfortably walk along the roadway shoulders when necessary”. A huge red flag is that many “pedestrians” are not able to walk safely or even at all, especially near OHSU. There’s no way anyone blind, in a wheelchair, using a walker, infirm, etc. can safely walk on that street without a sidewalk.

Second, the “loophole” of 33.641.020.A. certainly does seem like a loophole. BUT it refers to “mitigation as required by 33.641.020.B”. That mentions requiring “measures proportional to the impacts of the proposed use (including) improvements to the local pedestrian and bike networks…” It seems like PBOT could easily have found that that section could be used to require sidewalks in front of the project.

Again, I’m not saying this decision was wrong, because I don’t know anything more than what’s in the article. And it could be the decision DID address those examples above. But those are at least examples of the kinds of things that reviewers miss. It happens all the time.

Thank you for this long, informative comment, qqq. Let me fill you in a bit more.

The NA decided not to appeal (and the deadline has passed) so as to not mess up the developer’s building schedule. The NA and developer have a cooperative relationship, and the developer is willing to, in fact gives the impression of wanting to, build a sidewalk. His building down the street has a handsome sidewalk with big bio-swales.

The problem is that the city won’t give the developer permission to build a sidewalk. The NA’s beef is with the city, not the developer, so this isn’t a Nollan-Dolan proportionality issue.

From what I can tell, the problem is with the existing infrastructure (I see water and gas on the engineering plans) which would lie under a new sidewalk. A sidewalk could be put in, but the city doesn’t want to spend the $1.6M it would take to rearrange the pipes.

Let’s take this private.

A heads up – the survey of ‘what makes it hard to build in Portland?’

https://www.portland.gov/bds/documents/housing-regulation-survey-results-spring-2023/download

has a fair number of complaints about them pesky PBOT people and their damn sidewalks and infrastructure. I anticipate the report will be used by some at PBOT to further reduce the minimal work currently often asked for.