I read a lot of BikePortland comments. Actually, I read all the comments, even the ones that Jonathan approves before I get to them. About 30,000 comments last year. (Yes, it probably does do something to your brain.)

The caliber of your comments is impressive. Sometimes a news post seems merely like a cue for the knowledgeable discussion that follows it.

Every so often, though, I push a comment through that I’m pretty sure is incorrect. We don’t have time to fact check comments, but sometimes curiosity gets the better of me and I might quickly try to find out, say, which neighborhood is really the most dense in the city (the Pearl), or to verify which neighborhood coalition represents the largest percentage of the city’s population (a tie between Southeast Uplift Neighborhood Program and East Portland Community Office at around 26% each).

Some of that simple factual information, “which is the fastest growing neighborhood in Portland?” can be surprisingly difficult to find.

That’s why I was excited to hear Michael Montoya, the interim director of Portland’s Office of Community and Civic Life, speak to my neighborhood association last week. His topic was Civic Life’s Portland Engagement Project (PEP).

This year the PEP will release an information-rich, interactive map of neighborhood profiles made in collaboration with the Portland State University (PSU) Population Research Center.

Data from a number of sources will be aggregated: the 2020 census; the American Community Survey; Feeding America food insecurity data; CDC Social Vulnerability Index; the book Portlandness: A Cultural Atlas; and National Center for Health Statistics Life Expectancy Estimates.

This will be an invaluable resource for city employees, advocates, the public—anyone who values accuracy, even BikePortland commenters. The great thing is that all this information will be in one place—demographics for every neighborhood will be a click away. (And technocrats will appreciate the work that went into adjusting the data to neighborhood boundaries. For example, the federal government reports census data in census blocks, which don’t align with the neighborhoods. It’s a headache which the profiles make go away.)

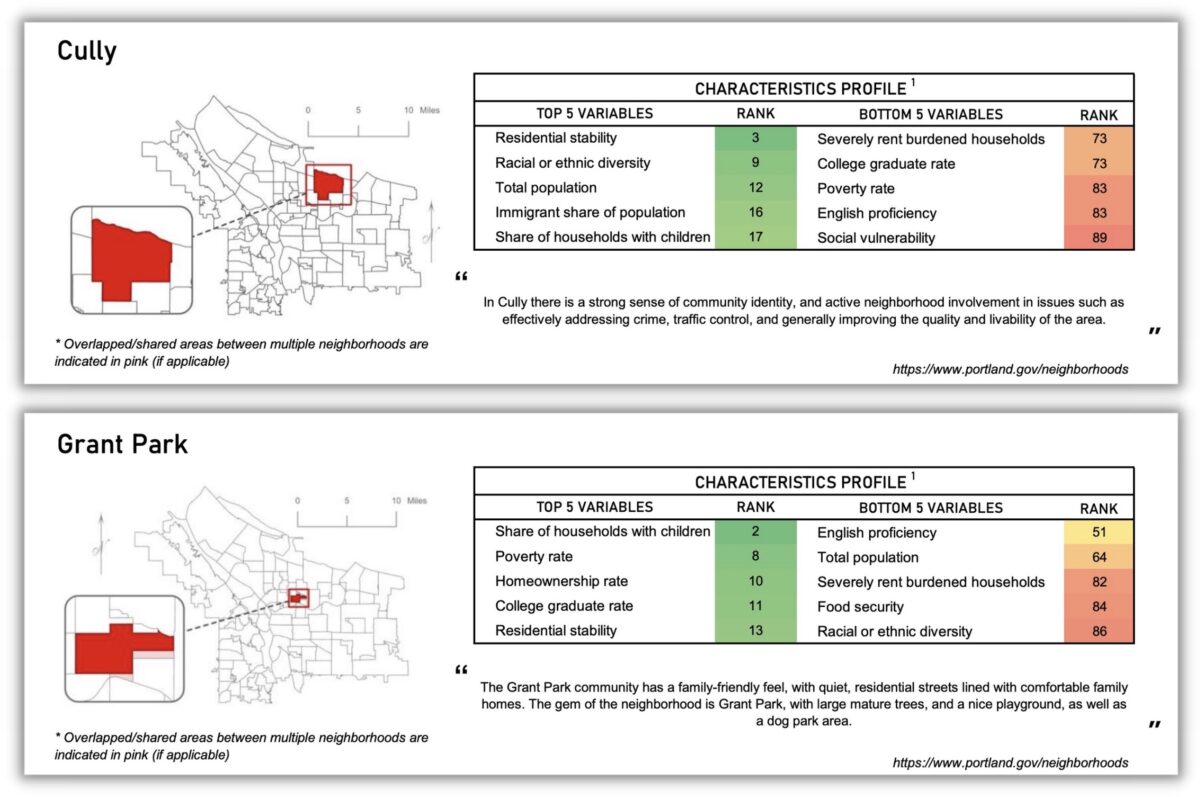

Here is the preliminary profile of Cully. You can see that Cully is one of the most racially and ethnically diverse areas in town, and that 13% of it’s residents are “severely rent burdened.” A quick glance at the Grant Park neighborhood shows that it is one of the wealthiest in the city. What does your neighborhood look like? Check it out in the preliminary profiles of all 94 neighborhoods.

Montoya pointed out that the work on the Portland Engagement Project is being done in the context of “the herculean task” of charter reform, and that there is a “debate happening in the city right now around who should usher in these transitions.” Currently, city engagement with the public is not good, his office is grappling with what future engagement should look like.

Listening to him, it occurred to me that the public-facing charter reform transition is essentially a map reconciliation project.

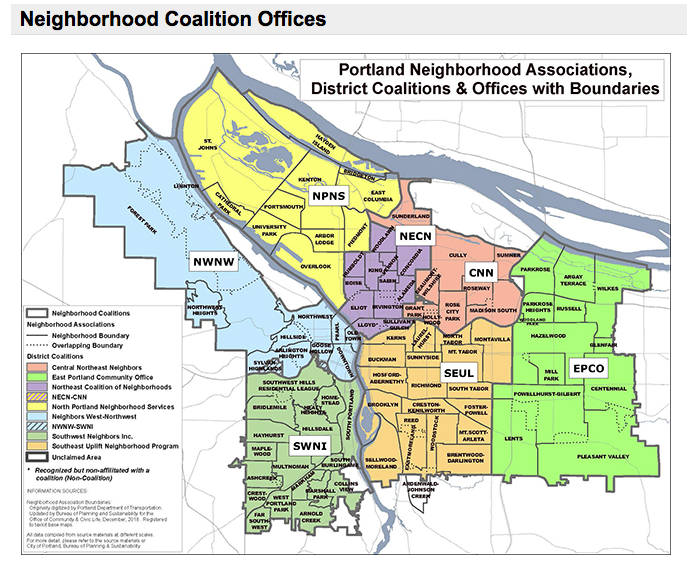

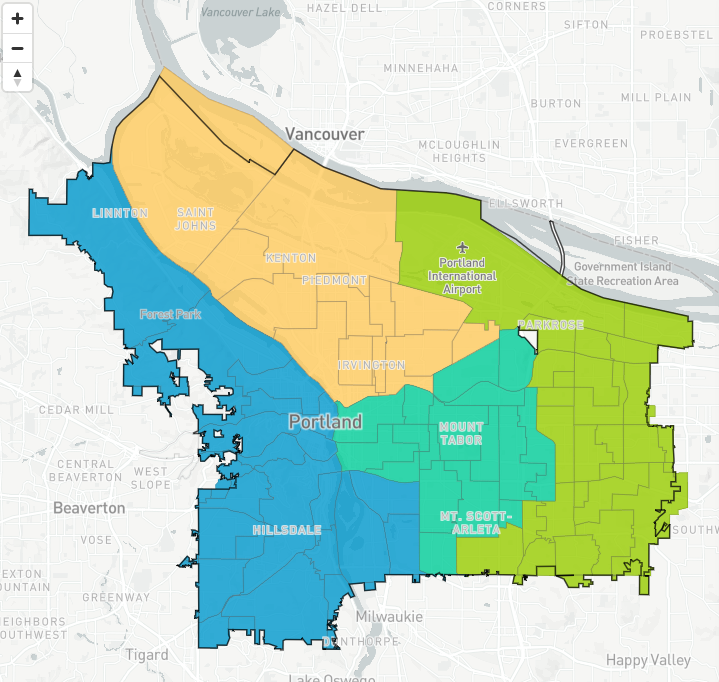

Portland groups its neighborhoods into seven coalitions. How will those seven neighborhood coalitions map onto charter reform’s four council districts? Will neighborhood coalitions be retired, with district offices absorbing the support work they provide for NAs?

For example, the charter transition will need to reconcile the neighborhood association (NA) structure with the new district structure. Portland groups its neighborhoods into seven coalitions. How will those seven neighborhood coalitions map onto charter reform’s four council districts? Will neighborhood coalitions be retired, with district offices absorbing the support work they provide for NAs?

This might not sound like anything but paper shuffling to those unfamiliar with the central role of NAs in the city’s engagement process, but it really is transformational. In a city without district representation, where each commissioner has been elected “at large” by the entire city for over 100 years, the neighborhood association structure was created to provide “channels of communication” between City officials and “the people of Portland.” At large voting and the neighborhood association structure have worked symbiotically for almost 50 years, they go hand and hand.

Montoya talked about the history of Portland’s NA framework. It came about at the end of the Vietnam War, and just after Watergate:

. . . the distrust was maybe even higher than it is now. Forming neighborhood-based associations was a way to influence and provide some check and balances on governments that were completely non-responsive.

But over the past few years NA primacy has been challenged—by former Commissioner Chloe Eudaly, by the director she appointed to the Office of Civic Life, Suk Rhee, and by culturally-specific organizations which would like a comparable seat at the table.

It has even been questioned by BikePortland readers, remember the Fremont and Alameda diverter controversy? There sure was a lot of confusion about what power a neighborhood association holds.

The reality is, today’s neighborhood association are mainly able to influence projects through their role as information conduit between neighborhoods and bureaus. They can pass on concerns and suggestions which PBOT will take into consideration. And that’s it. Fremont at Alameda now has its bike-friendly greenway protecting diverter, despite the initial neighborhood vote.

Portland and the country once again find themselves in an era characterized by mistrust of government and complaints about lack of representation. Our solution this time around has been to change how we vote and the way we are represented. What is still to be seen is what the working relationship between district city council offices, neighborhood associations and city bureaus will look like.

The Portland Engagement Project wants to hear from you and will be begin community listening sessions early this year. In the spring the City and PSU will host a summit to discuss public engagement practices, and in mid-2023 the City will host informational meetings to share the neighborhood profiles. Stay tuned. We need to make sure our voices are heard in the next era of civic engagement in Portland.

Thanks for reading.

BikePortland has served this community with independent community journalism since 2005. We rely on subscriptions from readers like you to survive. Your financial support is vital in keeping this valuable resource alive and well.

Please subscribe today to strengthen and expand our work.

It’s always worth reminding that neighborhood associates are private entities afforded a couple special mentions in city code, but otherwise serve in no official governmental capacity. It’s never made sense to me, in that light, to use them in a population-based official district capacity (I stress this only because it seems many are trying to do just that, as much as possible).

I think the districts being as large as they are, the hyper-local focus of NAs may still have value. And yes, their boundaries will inevitably cross district boundaries in many spots, as they already do for other districts (state/county/federal).

Hi Damien,

The Coalition offices which provide support (web page, accounting, newsletter) for the area’s neighborhood associations receive funding from the city (my guess is that there are between 2 and 3 FTE per office, plus rent). In exchange, the coalition and each NA must follow open reporting, sunshine laws, have bylaws, keep minutes, follow Robert’s Rules for public meetings and report compliance back to the city every month. It’s pretty arduous.

In some ways it’s similar to the relation between a charter school and the entity which grants the charter.

A lot of rules and regulations come with accepting government money.

Also, my impression is that there are more than a couple mentions in city code. NAs receive special treatment, with fees waived, for presenting land use cases to city council (providing the reporting is correct), for example.

This is all true, but not in conflict with my statement. NAs do have many requirements (that are voluntarily accepted by NAs in exchange for those special treatments), but one of them is not to be equal in terms of population or representation, which I think is key to a legally empowered democratic legislative body. Thus, I don’t think NA boundaries should have an effect on the city districts beyond what might otherwise be “immediately convenient”.

The city-imposed requirements for openness, transparency, inclusion, and democratic norms are what differentiate NAs from “culturally specific organizations” that are essentially conventional non-profits that are connected politically and financially. NAs are volunteer run, and do not have paid staff.

Because I’m a big fan of participatory democracy, I’m a big supporter of the NA system, and would welcome other organizations that follow the same rules to participate on an equal footing.

So that those that have the means and free time have a voice? I’m the only one on my NA board that is less than 50 years old, and despite 30% of the neighbors being renter, everyone on the board are home owners.

I think NAs are great for community building, resilience and is an important voice to have, but they are far from a democratically representative body and shouldn’t be thought of as the voice of the neighborhood.

I agree, which is why I would welcome other organizations to participate in community decision making, so long as those organizations were run in a democratic and transparent fashion, and were open to all.

By the way, one big reason why renters, especially young renters, are underrepresented on neighborhood association boards is that many may not see their current situation as permanent or long-term enough to invest in building the community in which they live. This is a perfectly rational decision on their part, and I too have been much less engaged in neighborhood politics when I was a renter (which I was for almost half of my adult life).

Your NA board might not reflect the diversity of your neighborhood, but it’s democratic. FWIW, my NA has had renters on its board for I’d guess the past decade. One was even President.

Some NAs are democratic (majority voting only with modified Robert’s Rules), but many are consensus-driven which isn’t the same thing. I’ve been a renter my whole adult life and when I lived in Portland I served for many years on neighborhood boards – it was never difficult to get elected – in Sullivan’s Gulch and in Hazelwood. Yes, most board members are elderly homeowners – they have lots of free time – but there were always some younger members and renters too (but not as many young renters). NAs are a concentrated group of active volunteers who really believe they can and will improve their community – their optimism can be infectious – and they really can make a difference, put on fun events, influence city hall, and actually get shit done.

It’s not democratic when the number of people voting is less than 15 in a neighborhood of ~6,000 people. NAs are a flawed way of local representation in today’s time.

There are ways to have better representation and community engagement. I look forward to the charter reform hopefully fullfilling a role that NAs are simply unequipped to handle.

It’s democratic when it’s open to all and everyone can participate. Many people may not have the interest or feel the need to participate in an election — that doesn’t mean it’s undemocratic. Many NAs have vacant seats, so anyone who wants can have a seat on the board. That makes things inclusive, but makes elections pretty dull.

Okay, if your definition of “democratic” is that technically anyone can participate. Just like in Alabama, right? So, how about this: “It’s unrepresentative.” The NA is not an accurate Representation of the people who live in the neighborhood, because, for various reasons, only a certain type of people participate.

Yes, NAs are participatory, not representative, so yours does not represent you the way, say, Donald Trump did when he was president. NAs should not claim to speak for everyone because they don’t.

NA’s can appeal a land use decision to the state agency and have the city pay for the appeal. It’s rare but it does happen. East Portland NAs get a financial allotment partly based on population.

It is naive to think that NAs, or indeed Coalitions follow all the rules you list. You might have heard of the scandal at one coaltion, Southwest Neighborhoods, Inc. (SWNI), with mishandling of funds so bad that the city ended their contract and is using city staff instead. Across the city, the fees waived for appealling in land use cases have helped neighborhoods delay and increase costs (if not entirely killing) of needed housing projects, including ones that would be majority or entirely affordable.

SWNI is not a neighborhood association.

Do you know of any recent cases where a neighborhood association killed a much-needed housing project? I’m not saying it has never happened, but it is rare — neighborhood associations have no special power to stop anything, and I know of several recent cases where the neighborhood has helped move projects forward and make them better for their future residents.

One example is 5050 N Interstate. It was planned to be a multifamily building with housing to be ownership under Proud Ground’s model of ownership, and aimed at those who had been displaced by those living in the neighborhood. Approved by the Design Commission, but then the Overlook NA appealled the approval of smaller retail space. The resulting delay resulted in a loss of the funding, and a different building (all rental) is being built. So the homeownership opportunities were lost.

I listed a significant case in a reply, but I don’t see it here.

swni’s issues (and there were some, but NOT mishandling hundreds of thousands of dollars as laughably claimed) were used by eudaly to put the shiv to homeowners in general and NAs specifically. ted gleefully threw eudaly under the nearest bus and then let hardesty give the knife the last twist. ted is no fan of NAs but likes his hands clean!

the person who spearheaded all that swni fighting was not only a member of a neighborhood association (part of swni), she led a nimby fight with that NA to oppose a large housing project! they then joined the ‘leopards eating faces party’ when the delisting of swni meant her NA had no money – and far more importantly, no insurance coverage – and could not function for quite some time, something she complained about loudly.

look, there are good NAs trying to make their neighborhood better, and there are bad NAs trying to enforce their vision of life on others, and those which are a mixture. don’t like what yours is doing? freaking join it and change its course. it’s an avenue of change given to people in city code to try to influence things done by city, and if you want things better, why not use it?

beats moaning on the intertubes about them.

NAs are decidedly *NOT* “private entities.” They are public entities in every sense of the word “public,” as they belong to the people who live in the neighborhood. They have requirements for transparency, disclosure, etc, which makes them the opposite of “private.” Anyone who wants to participate MUST be allowed to participate.

They ain’t perfect but they certainly ain’t private.

Coalition boundaries have been the same for over 20 years. The 4 city ward boundaries will change every 10 years after the census, as required by law.

I was born and raised in Portland where I have lived since 1971. My consistent experience over the last 25 years is that neighborhood associations attracts dedicated people that for the most part have great intentions. But over the decades I have watched neighborhood association participants increasingly become those people with the time, resources, and experience to participate. Participation eludes most Portlanders especially those who live in cost-burdened households. Ironically these are the lower or negative net wealth residents who actually have the most at stake in government decision-making. They understandably lack the time and resources to participate in open ended, advisory civic engagement where no one knows exactly if and how their participation will change outcomes. There are lots of needs changes that could and should be made address this uneven access to power. But I believe without solving the systemic and societal problem of run-away inequality, we need to at least make a transition from civic engagement for a few to participatory democracy for all. We need mechanisms of participatory democracy that actually delegate power within parameters to ordinary residents while appropriately resourcing their time and expertise to equitably participate. Until we start making these kind of transformation to democracy beyond elections, it is going to be the same usual suspects showing up and influencing outcomes for those who can’t.

An opportunity to begin establishing mechanisms of participatory democracy actually came before the City Council last week when the Charter Commission presented a charter amendment to establish a participatory budgeting program in Portland open to all residents. It is now up to the City Council to either refer the amendment to the voters, modify it and refer it to the voters, or do nothing.

Portlanders have been asking the City Council to launch PB in Portland for over 5 years. Portland remains the only major City on the West Coast from LA to Vancouver BC that has NOT launched a municipal PB program. East Portland youth are already implementing a pilot with State ARPA funds.

It is not too late to urge the City Council to not miss this chance to finally bring participatory budgeting (PB) to Portland.

PB is not a panacea to the problems above but it is start that would improve the status quo, a status quo that provides extremely uneven access to a primary way governments exercises power: public budgeting. And as a late adopter Portland is in a prime position to learn from other municipalities in applying demonstrated strategies to maximize equitable participation and outcomes through PB open and accessible to all.

I’d definitely be interested in PB, but it seems to suffer from many of the issues you raised above regarding NAs, including being more available to people with the time and inclination to participate (something true of almost everything in this world).

How do you overcome those hurdles to make PB “truly democratic”?

Jim, the community I live in, Greensboro NC, recently finished its 5th round of participatory budgeting since 2015. Ours has had many issues, but there is a growing local trend towards neighborhood associations and government agencies dominating the process at the expense of independent participants, let alone the poor and the homeless – just like everything else in government. PB doesn’t solve your problems and inequalities, it exacerbates them.

Watts & David,

Yes this question of “won’t PB be captured” comes up all the time. It is an empirical question that researchers have actually investigated over and over but too often those who raise the question never look at the findings. And people often confuse questions about the degree to which PB produces more equitable participation and outcomes, with the real question: does inevitable elite capture worse than the status quo. And on this the research actually quite clear: PB consistently shares power with more and more diverse participants than traditional public budgeting processes, a status quo that is also continually subject to the same societal affects of run-away inequality. I would challenge you David to demonstrate that this isn’t true case in Greensboro, NC. Please show me the evidence that PB has made things worse?

The reality is that governments delegate budgeting power all the time to City Bureaus in opaque and unaccountable ways. IN our new-liberal times, they also increasingly allocate funds directly to private businesses and non-profits (deemed equivalent to “the community”) who are even less accountable to the public. These decisions are often rife with elite capture.

So what is the solution to that existing problem of elite capture? Is the solution more privileged and “enlightened” residents to speak on the behalf of the unrepresented? Electing more responsible elected officials? How is that working for us? Why are we so quick to assume that sharing some power and responsibility in public budget decisions will make the elite capture problem worse? SHouldn’t the public be the source of sovereign power in our democracy and on that basis worthy exercising some budgeting power. No one is talking about removing government or private intermediaries that, again, no less and demonstrably more subject to elite capture.

The impacts of sharing both power and responsibility through PB so often overlooks the facts choosing to strangely view as only a threat to the public interest. And for every anecdote of white homeowners proposing and selecting a dog park near there homes, you never hear about what happens next when new voices enter the fray and argue for different, more just priorities. Nor do you hear the stories of privileged residents who actually dropping their project ideas and in acts of real solidarity get behind the ideas of their less privileged neighbors. For the counter point anecdote of this see this 2012 NYT article where a group of residents dropped their community garden project to back a group of girl students fighting to put doors on their restroom stalls so that they could use the bathroom with privacy during school hours.

The argument PB somehow will be worse than a status quo so lacking of transparency and accountability because it will some how be more subject to elite capture, just doesn’t stand up. Coming from some “liberal” voices, this reasoning becomes a truly bizarre case of making the perfect the enemy of the good in order to defend a failing status quo.

And meanwhile the proven strategies for maximizing more equitable participation and outcomes are being demonstrated and applied to PB processes around the country and globe. As I mentioned these are the very practices that could and should be applied in Portland.

This young adult from East Portland said it all (much better I did) this morning before City Council:

https://youtu.be/fdVGnNheEec?t=432

For the record, I started off my response with “I’d be interested”, which I hope doesn’t read as “I can’t support that”.

In your first post, you wrote:

How would these folks find time to participate in PB if they’re too busy to participate now? Also, how do you ensure highly motivated “single issue” folks focus on the needs of the many rather than just their pet program? I don’t see either of these as insurmountable hurdles, but it does seem that PB is susceptible to “activist capture”.

But I’m all for devolving power and giving residents more voice, and so I remain interested, especially if the process is open to everyone.

Thanks Watts. I didn’t mean to cast you and David in the same swath.

I’d answer your question in two ways. First, what are some of structural features of PB that make it more equitable and accessible relative traditional municipal budgeting (the status quo)? And second what are some of the strategies and practices being applied to make PB more equitable and accessible over time? Where the former improves on the status quo, the latter represent demonstrated methods for making PB more accessible over time and space.

I don’t have the time to cover every feature of both these but here are some things to consider.

Some structural Features of PB relative to Status Quo Public Budgeting

I would say first that participatory budgeting as implemented in most places, changes (1) who makes the decisions (residents instead of public officials, (2) the kinds of decisions they make (binding within parameters instead of advisory decisions) and (3) where decisions get made.

The latter means decisions are not made in City Hall but in public assemblies throughout the City that are more accessible to ordinary residents. PB is more common in Cities with district representation and in most the process is built around City Council districts. This directly links participatory and representative democracy. The public assemblies occur in both the deliberative (idea collection) and voting phases. The process design and project development phases also draw representatives and budget delegates from the community. They can be selected by the community, by elected officials, or- in the case of the Steering Committee- by democratic lottery in order to guarantee rather than aspire to full representation.

The process design phase also levels the playing field by generating a PB process rule book which details how much will be allocated through the PB process, what types of projects can be funded, who participates and how at each phase, and other key details of the process. Here is an example of a PB Process Rule Book in New York City.

Some Best Practices for More Inclusive PB.

The range of additional strategies to make PB more accessible to all, are too numerous to mention here but I’ll outline a few, some of which are obvious.

1) Civic Engagement Best Practices: Fund and implement the usual best practices for equitable civic engagement strategies (food, transportation, interpretation, translation, etc).

2) Targeted PB Process Education & Training: Targeted outreach and training to culturally specific and underrepresented groups so they start the process with at least an equal understanding of the process and phases or better yet have the expertise to lead through paid opportunities. This is very much what we are trying to do in Portland with Youth Voice Youth Vote PB centered on East Multnomah County youth/young adults.

3) Pay People: Compensating people for their time and expertise in the steering committee and budget delegate roles to reduce the material barriers to participation.

4.) Culturally Specific Process: Provide culturally specific opportunities for participation in each phase within a larger process open to everyone.

5.) Equitable Allocation to PB Processes: Allocate more funds to PB processes in high need districts. They do this in Brazil where PB has been shown to increase investment in public health and less affluent neighborhoods. In Portland this might involve a Citywide PB process implemented in the four new City Council districts but not on an equal-per-capita basis. More funds per-capita could be allocated in, say, the Councilor District encompassing East Portland.

These are strategies and others are being tested and refined by a global community of participatory budgeting practitioners and researchers, and ordinary residents through both “academic” and participatory/community based research methods. A core principle participatory budgeting, is to apply the same transparency and accountability to the process itself through robust assessment and evaluation to the end of making the process as equal as possible. This is a never ending goal for any government process or institution.

Which is why the argument that “PB will just get captured by the usual suspects” as a reason not to even try it is so bunk. It is the most lazy of excuses in service of the status quo because any government process will be more or less captured by elites, especially over the primary way governments’ exercise power: budgeting.

Critiques of PB in this vein usually don’t address the alternatives, either the status quo or to PB as it has been practiced to the end of making it more equitable overtime in process and outcomes.

Really, they’re using “residential stability” as a metric?

In my experience in SE, most neighborhood associations are not representative, being disproportionately older homeowners. E.G. the Richmond neighborhood is about half renters according to census, but the NA has, for the last 20 years, been almost exclusively homeowners. Out of the 11,000+ residents, about 15 show up at elections for the neighborhood board (1/10th of a percent?). Opposing new rental housing projects.is norm for many neighborhoods. The reasons given out loud may be different: blocked views, increased traffic, and “residential stability”, but underlying it is opposition to renters and/or those with less income. Yes there are some neighborhoods, such as Cully, which work hard at representing all of their residents. But in my long experience, the “neighborhood system” is a mechanism for those with the time, money and connections to have an outsized voice in the governance of the city.

Doug, when you were on Richmond board, what did you do to attract renters, and were your efforts successful? It is very unclear to me how to make low level civic activity inherently interesting to young people who are in a phase of life where these issues are generally not interesting. I would like to learn from any successful strategies that you deployed.

Maybe we should all just agree that getting young renters involved in neighborhood politics is very difficult and stop using it as a cudgel to bash those who are doing their best to make their communities a better place for everyone.

In the Municipality of Saanich, a suburban area of 100,000 residents near Victoria BC, apparently all land use cases must go before a local “ratepayers association” of homeowners and also a “Renters Association” before getting formal approval – they basically institutionalize local participatory governance.

I personally got the neighborhood newsletter distributed, through their monthly renter email, to residents of 5 multistory apartment buildings in the neighborhood. I sent the newsletter, and those building owners copied it into their newsletter to tenants. Admittedly, we only got about 3 renters to attend a couple of meetings.

I disagree with your characterizations of the average NA attendees, though. Yes there are some who are “doing their best to make their communities a better place for everyone.” But, what I saw in my neighborhood was a good number of these homeowners doing their best to stop any more people from living in their neighborhood. By fighting zone changes, and indeed fighting buildings that complied with existing zoning, they were actively trying to make the lives of those who couldn’t afford to buy a single family house worse, telling them they could go live elsewhere, further from their jobs, further from the parks, further from the shopping and further from transit.

I think the trick here is realizing that folks with means and privilege often and quickly convince themselves that what’s good for them is good for everybody. Our whole dominant market philosophy is built on that delusion.

Don’t confuse difference of opinion with malign intent (as you’ve come pretty close to doing in your post).

Your experience may differ, but pretty close to 100% of the people I’ve worked with in the NA context have been involved for the right reasons, even if I’ve strongly disagreed with them on one or more particular issues.

Neighborhood Associations are one of the few ways in which an individual can influence city policies in Portland. The primary dialectic in the city of Portland (and Multnomah County) is controlled by taxpayer funded nonprofits that have the staff, infrastructure and paid time to lobby and unduly influence our leaders. Democratic, open to all NA’s give a least a fighting chance to the “little guy” to be heard over the loud and mostly extremist Portland area nonprofits.

Some people do not want “the little guy” to be heard. Those who attack the neighborhood system tend to be of the political persuasion that wants to speak for others but not let them speak for themselves.

You got that backwards. It shouldn’t require dedication to the NA system to be heard. The extremely low turnout to most NA meetings is comprised of 0.02% of the neighborhood, yet they are expected to be the voice of the neighborhood. Make community engage easy and accessible. A great example is the traffic safety report tool that PBOT has, or the PDXReporter app.

One of the souring events in my own NA experience was my old NA’s…let’s say most influential (and pragmatically, if not officially, most powerful) committees met weekly, weekday mornings. When asked to move that to evenings like other meetings so that folks working standard work days could attend, they countered with (paraphrasing) “Well, we polled our attendees and members, and they all like this time” (keeping in mind all the attendees and members were retired or real estate developers who basically get paid to attend these sorts of meetings). They rebuffed any further requests.

I’m 100% in favor of this.

(Though, referencing your example, I do recall the recent discussion here recently about how empowering the public to report safety issues was somehow unfair.)

NA’s don’t really allow the “little guy” to be heard, because the “little guy” doesn’t have the time to participate in the NA’s. They’re largely a voice for older, well-off homeowners who aren’t exactly lacking in political clout in this city.

Hi Will,

One thing that Civic Life has never done (at least not done recently that I’m aware of) is to offer guidance or best practices to NAs—NAs have been left on their own to figure it out.

When I was chair of our transportation committee, if I needed to know how SRTS was being received, I’d get my rear end out the door and walk with the parents and kids to school. I’d stand on the corner and ask them questions. We had contacts w the PTA, with school admin …

I’ve even flagged down drivers to ask about their thoughts on diverters.

Set up on a street corner with a notebook and a whole lot of people will stop to tell you what they think.

We poll, we send out surveys. We approach our neighbors. I could go on, and have always been willing to share.

Till recently, however, Civic Life has been politicized to an antagonistic relationship with NAs. (It reminds me of wanting to make government “small enough to drown in a bath tub” and then complaining that gov doesn’t work. Only substitute NA for gov.)

NAs are valuable and aren’t going away, the question is how to most effectively integrate them into the new representative structure.

If the “little guy” has too little time to participate in civic engagement, how do you make sure they can meaningfully engage? It seems like an impossible requirement to make participation not take any time.

Should we just give up on the concept of civic engagement if there are some people who are too busy to do it? No matter what you do, there will always be people who are too busy, have conflicting schedules, can’t show up for in person meetings or don’t have the tech for online meetings, etc. It feels like you are asking for the impossible.

“Give people a voice, but only if it’s effortless and takes no time because otherwise it’s too unfair.”

You pay them, provide food, provide childcare, and provide translation to start with. You set meetings at times that people can actually attend and you advertise them aggressively in multiple languages and through multiple channels. You proactively ask the folks who aren’t participating what is hold them back and how to fix those barriers.

I would love to get paid for this! Maybe PBOT could set up a cash station at their open houses where you can exchange your empty sheet of colored dots for $20.

Thats why we have a representative democracy. Most people don’t have time. Vote for the politician that represents your goals and they should be seen as the voice of the people and to achieve the goals they were voted in for.

For projects that need feedback and community outreach, look no further than what trimet is doing with the new service concepts. Open houses, neighborhood coalition meetings, and online feedback surveys. It requires very little time and effort to tell trimet that a route change is effective.

I’m surprised; what you want sounds very much like a preservation of the status quo. Trust the politicians, and if you want to make your opinion known, fill out an online survey or, if you have time, attend an open house.

Myself? I want something a little more empowering.

Except Portland’s current form of government isn’t representative. That is where a lot of issues come from.

Exactly — this is one reason I want to devolve power downwards to the community that have a clearer vision about what is best for their neighborhood (which may be different from what others want for theirs).

“Representative democracy” is never truly representative (in the sense you mean it), and probably can never be.

Ironically, many times when I’ve been trying to influence City policies or projects, sometimes alone but often with other neighbors, our own neighborhood association has been our OPPONENT. And it’s frustrating to get two minutes to testify when they get 15, and they get instant credibility as being representative of us. It’s also frustrating the NA testimony is from people that a project or policy has no impact on, while the people on my non-NA side are facing, say, losing their business or having their home condemned.

One thing I especially dislike about NAs is that City staff often use them to bypass public input and notification. When I was a neighborhood association president, City staff would regularly call me to get my approval for something, and they viewed calling me as proof they’d done public notification. They hated when I’d tell them I don’t speak for other people, and that they need to contact the people their project impacts, because they knew those people might have concerns or objections.

My particular example of what I don’t like about NAs is having my NA president meeting outside my house with public staff discussing condemning my house (NA president was in favor of it) while I was inside unaware they were meeting, and nobody bothered to knock to involve me in the discussion. (I’m sure the public staff then reported that they’d met with the NA and there were no objections!)

When has a NA had 15 minutes to testify on anything ever? And why would city staff not want you to confer with your neighbors? Everyone knows (or should know) that a NA president can’t assert a position on behalf of their organization without approval, which means public notice, discussion, a motion, and a vote.

It sounds to me like you were dealing with some very misinformed, very unprofessional city staff.

I’m remembering testimony before the Design Commission, the Planning Commission, City Council and hearings officers in land use cases. At least some of those have allowed 15 minutes for NAs, versus 2 or 3 for individuals. I remember it from both sides–as an individual, and as a NA testifier.

I answered why staff wouldn’t want me as a NA president to confer with neighbors–because they knew affected neighbors were likely to raise concerns or objections.

I agree at least some of the staff I encountered were misinformed and very unprofessional. Those aren’t uncommon, even at high levels.

I’m also not saying NAs are all bad. One I was involved in for years was very effective and productive.

Anyone that trust ANYTHING that the Office of Civic Life puts out will be sorely disappointed. This is the same office that attempts to control what Halloween costumes Portlanders are allowed to wear, promotes marijuana use and says Neighborhood Watch group are racist. This is the bureau that needs to be defunded, not the police.

https://www.portland.gov/civic/news/2022/10/14/my-halloween-costume-okay

<sigh> Listening sessions. More colored dots on big sheets of paper. The whole engagement apparatus seems so broken to me. Count me out.

It’s important to be precise about the terms here. The *Coalitions* are different from the *Associations.*

As the Districting Commission does its work drawing district maps, I would hope that they would take the *Association* boundaries into careful consideration while giving the *Coalition* boundaries less weight. Otherwise, as your questions posed here suggest, the simple act of drawing political maps ends up having major policy impacts about the roles and powers of the Coalitions relative to the roles and powers in the district offices that will be created under the new charter.

More to the point, though, who controls the district offices? What are their purposes? How are they staffed and budgeted? To whom are they accountable? These are questions that only the expanded City Council elected in 2024 can answer. So, working on “engagement” in 2023 is one thing. But prematurely locking in particular structures for engagement is another. We, the citizenry, need to be careful that City agencies don’t get too far out in front of a city council that hasn’t been elected yet.