Vision Zero and speed limit reduction were the topics of presentations at a Transportation Research and Education Center (TREC) Friday Transportation Seminar at Portland State University last week.

Clay Veka, Portland Bureau of Transportation Vision Zero program coordinator introduced the bureau’s “Safe Systems” approach to speed management, and Portland State University Research Associate and Adjunct Professor Jason Anderson presented the results of two studies he conducted to determine the effectiveness of PBOT’s speed reduction efforts. (PBOT commissioned the studies.)

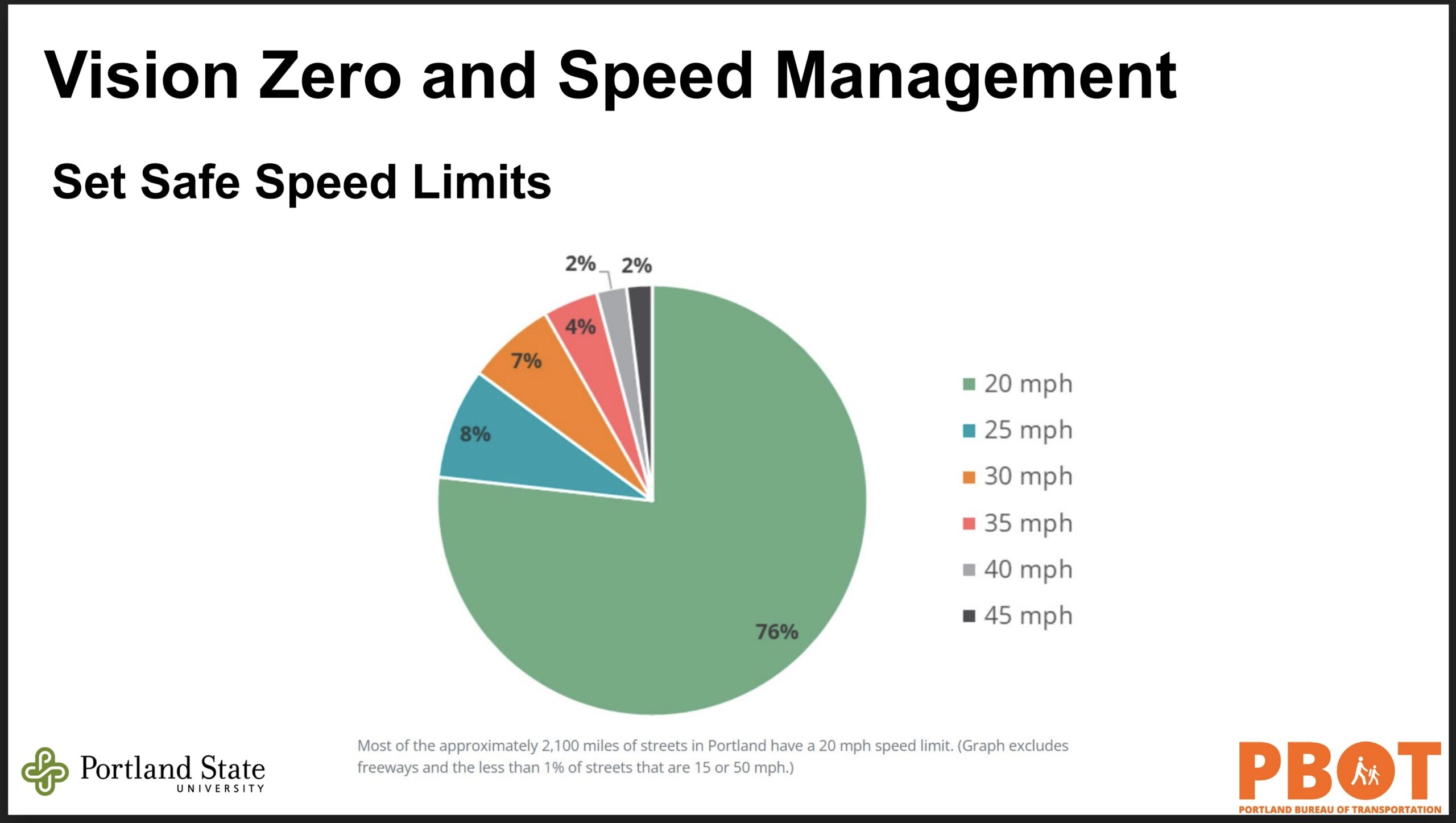

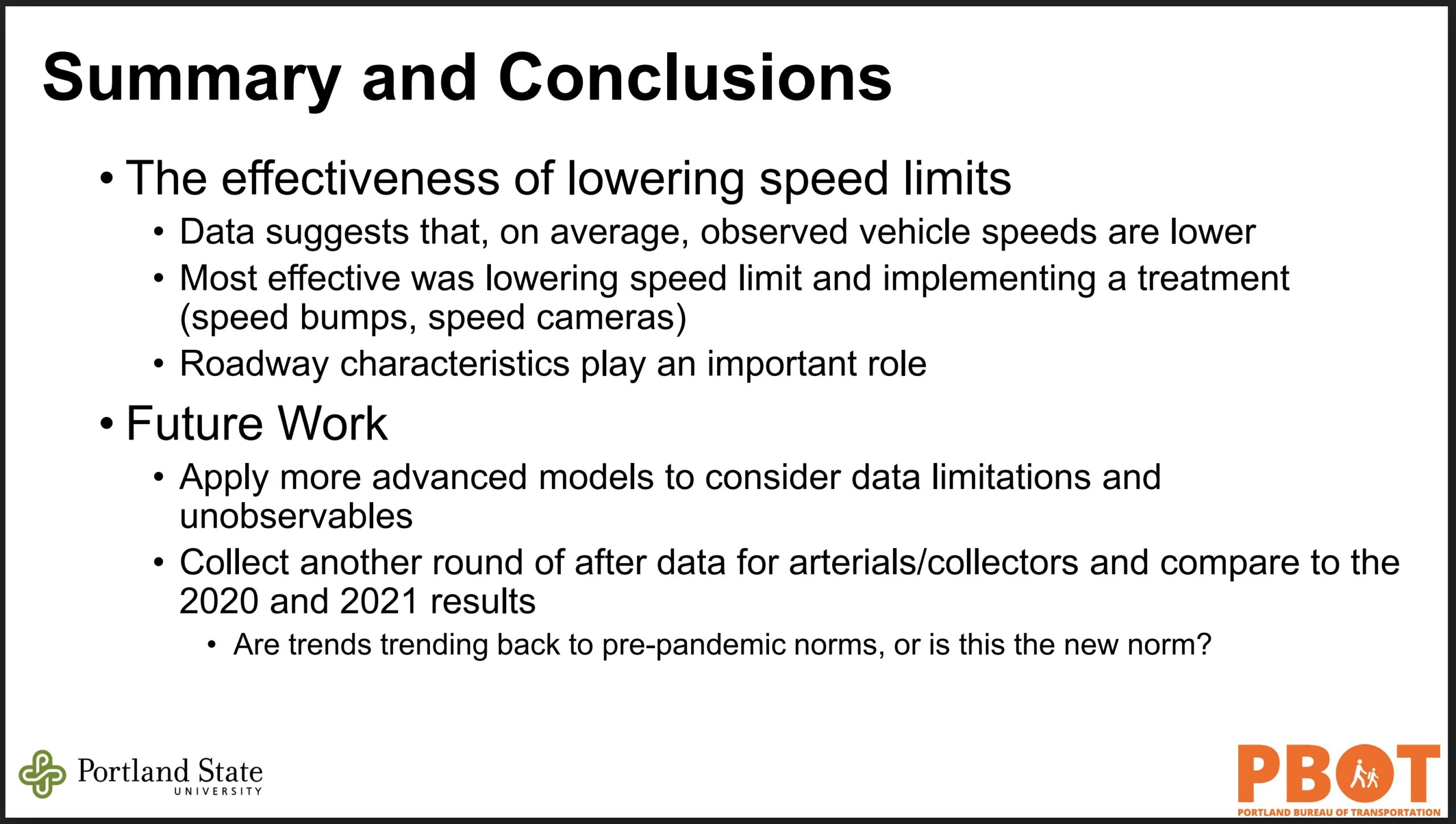

Anderson studied travel speeds before and after PBOT’s 20 is Plenty program swapped out 25 mph signs for 20 mph signs on small local streets and found that it successfully lowered traffic speeds, with statistical significance. Two years ago, PBOT touted that result as supporting the program’s efficacy, and it was covered by area media.

On Friday, Anderson presented data from an unpublished companion study, Speed Limit Reduction on Arterials and Collectors. PBOT did not have a high-profile program for the larger roads similar to the “20 is Plenty” campaign for smaller, residential streets.

The bureau used historical speed readings as “before” baselines, and collected post-speed-reduction “after” data in 2020 and 2021—during the middle of the pandemic. Anderson pointed out that the pandemic introduced confounding factors for which there were no experimental controls, such as riskier driving behavior and less traffic.

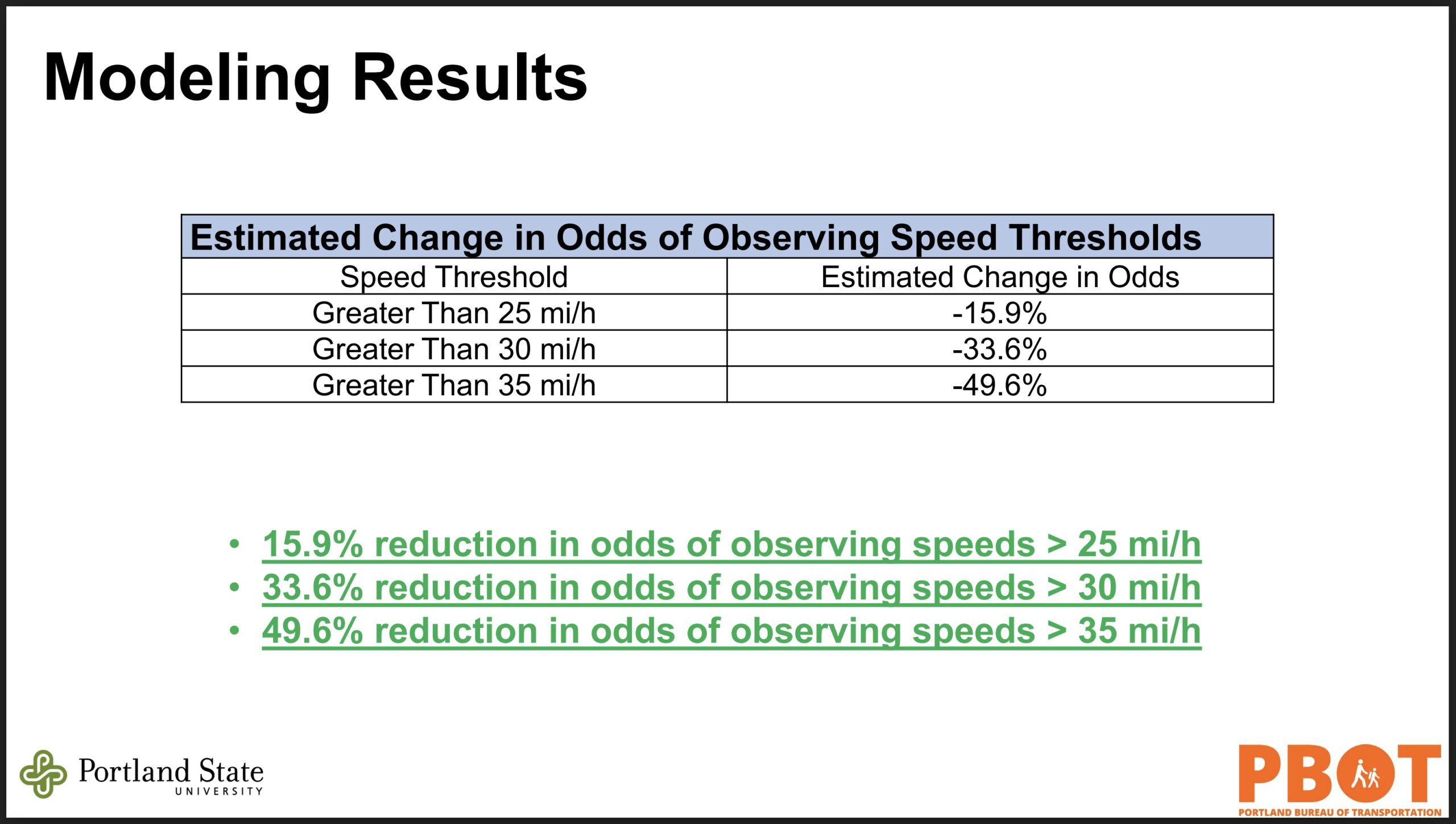

Despite pandemic complications, the study reported that reducing the speed limit by 5 mph resulted in a modestly decreased average observed speed of 2.0% for arterials and 2.7% for collectors. To save the reader doing the math, 2% of 25 mph is 0.5 mph.

Friday’s audience was underwhelmed by those results. A couple of questioners skirted the issue, but eventually someone got direct: What should policymakers with “limited resources” make of the “small gains”?

PBOT’s Veka fielded that question,

“Setting the speed limit is setting expectation, what is the appropriate speed to travel? And…that’s not enough, you can’t just do that. But it can be relatively quick compared to major redesign projects, and it can be effective. In partnership—adding those street-calming elements is really important. But I would say don’t wait. Do what you can now.“

In the face of possibly inconclusive study results, Veka might be too readily retreating from the efficacy of reducing speed. Reading “after” results in the midst of a traffic-altering pandemic could be like surveying the land in the middle of an earthquake. The methods could all be sound, but gosh, the earth is shaking.

Experiments ideally test one change at a time. Either you can try to determine the effects of a pandemic on observed speed, or you can test the effect of posting lower speed limits. When the world conspires to make both happen at the same time, it is difficult to tease apart the causality of your observations.

Thanks for reading.

BikePortland has served this community with independent community journalism since 2005. We rely on subscriptions from readers like you to survive. Your financial support is vital in keeping this valuable resource alive and well.

Please subscribe today to strengthen and expand our work.

In a study like this you need a control group. For example, they authors could compare speeds in 2019 and 2022 on parallel arterial and collector streets that did NOT have the speed limit reduced.

Perhaps the average speed went up on those other streets due to fewer people commuting to work, or less enforcement?

But it is also possible that speeds also decreased slightly on similar streets that did not have the speed limit changed, in which case there is no effect at all. I think that is unlikely, but we need to make the comparison to know.

Agreed. Extrapolating a ratio of speed reduction to posted speed, off this single study is junk science.

The ‘studies’ I’ve looked into with PBOT have been sketch. They don’t abide by what I’d argue are basic principles of research.

For example, they decided the beg barrel program reduced traffic after they measured traffic during the summer 2020 at the height of work-from-home without controlling for the reduction in overall traffic and ignoring that vehicle traffic increased on non-commuter routes.

I’m going to go out on a limb in that I’ve never studied statistics, but I have seen drug trials where each subject was used as their own control. You can do that if you have a lot of data points for both before and after the treatment. (In other words, not a binary of cure/amelioration or not.)

In the traffic speed study, each of those locations had many, many data points for both their before and after. If the pandemic hadn’t happened, those large data sets would probably have been adequate to show causality.

The pandemic seems to throw a wrench into all of the “after” data sets.

Or so it seems to me.

This is a crossover study and would require PBOT to change the speed to 20 and then to change it back to 25 (for example) for one randomly-selected set and to do the opposite for another randomly-selected set. I don’t think PBOT is interested in doing well-controlled studies, for a variety of reaons.

To be clear, PBOT commissioned the study, they didn’t carry it out. It was led by Prof. Jason Anderson at PSU who: “…is a research associate and adjunct instructor at Portland State University. Dr. Anderson’s expertise is in data analytics, particularly advanced statistical and econometric methods, with an emphasis on transportation safety, transportation economics, travel behavior, and policy (impacts of policy changes on safety).” So I’m going to go out on a limb and say that, at a minimum, the lead author knows statistics pretty well.

A poorly-designed study can use the most sophisticated form of statistical analysis possible and still be biased:

I’m willing to bet that Dr. Anderson would have loved to have the funding to perform a better-controlled study but when PBOT is your funder this is often not possible.

Do you consider the study poorly designed?

Yes. The impact of the pandemic on vehicle traffic was a huge confounding factor.

I’m a statistician and I work for the city. Before-after type designs are a poor substitute for randomized treatment designs and require many more assumptions. Randomization is the absolute foundation of rigorous statistics; doing without is possible and in many cases is the best you can do. But it’s incorrect to say that a before after study (especially without a control) can show causality. It absolutely cannot – you have no control over the before after. You can pretend and wave your hands and say you don’t _think_ anything changed. You can even measure some stuff and show no difference. But it is in no way close to being as good as randomized treatments. There’s a reason why epidemiology and other observational disciplines are difficult and require complex models. They lack randomization and have to do lots of compensating.

Thank you Jason.

The question has become, “Is this type of study worth doing?” My opinion is “yes.”

The study design is to look at a collection of various and diverse roads. You can consider each road as the site or host of a small before/after study of a population of thousands of drivers. Any given road can have a local confounding event, but by pooling the results, those effects get averaged away.

The question is, what about confounding circumstances which affect the entire set of roads—really big events? I can come up with a few that you can’t control for in a study of this scope even if you had a control group. For example, what if the price of gasoline plummeted and many more people began driving, causing most roads to become congested? You would get reduced speed in both the control and the study groups which would obscure the effect of the test.

But any global event that changes traffic behavior will also be known and obvious, so you will know if the study has been spoiled.

Most of the time there probably isn’t a large confounding event, so the data could be useful. Not rigorous enough for NIH, the FDA, or academic print journals, but possibly helpful to the transportation department of a medium-sized city. (I’ll reel in the word “causal” and substitute “useful.”)

But I’m just a retired hack computer programmer. Our first question is always, “what’s this for?” Commercial software or quick and dirty.

Randomization is not always possible so causal inference of observational trials is worth doing. For example, when well-powered RCTs are not available I definitely prefer medical treatment options/traffic engineering based on causal inference of observational data as opposed to some clinician’s/engineer’s “experience”.

PS: Some Bayesians might disagree that randomization is always the best way to handle covariates. (*ducks*)

I doubt the ratio of lowering the speed by 5 mph reduces the speed by 2% is a linear relationship through 100 mph. Just “doing the math” for unstudied speeds is bad research.

No extrapolation from the researcher, just my example to help the reader get a ballpark idea of the observed reduction. I’ve changed the wording.

The researchers calculated the statistics for arterials and collectors separately, and also separated between the roads with “after” end points in 2020 and 2021.

Furthermore, they binned the data into groups based on the original posted speeds, six bins, 25 through 45 mph.

He chose to show averages for the summary slide. The slides and lecture video are available at the TREC link.

That’s reassuring to hear. I think your rewording makes the study sound much more professional.

Thank you for helping to improve my post! Sometimes it takes an hour online to get the kinks out of the writing.

You might find the research slides interesting. Writing for a general audience at BP, I can’t slap on a figure with a bunch of statistics. But if you like log-linear regression models, you’ll enjoy the slides.

I feel like I’ve read before that speed limit reductions don’t do much for low-end speeding (people going 5 to 10 mph over) but do a lot to reduce high-end speeding of 10mph or more above. Which makes some intuitive sense.

It also really matters a ton whether it’s a multi-lane street or not. If there’s only one travel lane in each direction, the slowest car sets the pace. On a multi-lane road, cars can pass each other at high speed and that encourages higher speeds. So I would think a good study would look at those two road types separately.

***Moderator: This comment does NOT appear to be from PBOT judging from its backend email address. ***

20mph speed limits are a good idea. They are appropriate and indicate that Portland is serious about safety and culture change. Car/Truck speed is directly proportionate to injury/damage in crashes. If enforcement were also present, what would be the results? People speed because they know they won’t be caught/ticketed. There was a time when people did not wear seat belts and look where we are now. People used to smoke inside and look where we are now. Culture changes when government realizes there is danger and/or financial loss. People can change when there are carrots/sticks.

That is true, but Portland enacted this in such a half-hearted way it shows that they ARE NOT at all serious about safety and culture change. Look at a street like INterstate that has super skinny, unprotected bike lanes that disappear unnanounced under a viaduct next to a travel lane used by freight and buses, and this street collect bike and car commuters from a huge catchment of North Portland, yet the speed limit remains at 30, and drivers regularly exceed that. That is is just one example among dozens all across the city. 20 mph IS a good idea, but Portland IS NOT serious about safety and culture change

I’m not opposed to enforcement, especially automated enforcement, but it obviously has pretty clear limits. People speed everywhere in this country, and to be honest places like Florida and Texas have a ton of enforcement and dangerous fast motorists.

Infrastructure is the number one way to reduce traffic fatalities.

Asking nicely doesn’t work. Saying please slow down with cute yard signs does little. We need traffic enforcement in Portland now. How many other major cities have no traffic division and have a police force that also advertised that fact when they disbanded said division? It’s mad max out there. Where are the 600+ officers we pay for with our tax dollars? What do they do all day? Why did they wait 80 minutes to respond to reports of people with guns outside of Franklin high school? Where is the accountability? I’d be fired if I did literally nothing for 2+ years at my job.

Glad to see your comment. Unfortunately I feel like the PPB is winning the propaganda war they’re waging. They let nuisance or safety issues go ignored, allow insane street racing, wait 80 minutes to respond to literal gun shots (like one of the few jobs they seem appropriate for addressing), and claim they can’t do anything about it. They cite “staffing” but as you said, they have officers, what are they doing? Not something else it would seem, because nobody seems to have stories of officers doing what they’re supposed to in a reasonable time.

All this adds up to people starting to believe the obvious lie about defunding or the claims that the real problem is their hands are just too damn tied. It’s blue flu, it’s a strike.

Of course, this is just my impression given the evidence, and the frustrating thing is the only “sources” people seem to believe is what the PPB directly says or what they tell to reporters and gets printed in the news.

I tend to agree with you John and it bothers me that more of the political debates in Portland don’t talk about the role PPB plays in reducing public safety. It seems the only voices we hear from are either “ACAB” or “Cops are awesome!”. I’m very troubled by the conduct of the PPB and I believe they’re running a political game (through their union) of trying to make things so terrible that the entire city comes groveling back to them. And yes, I think they’re winning that information war so far…. because the only other voice we hear from is so anti-police that they limit their credibility. It’s so frustrating to me that we don’t have more leaders in this town that can be reasonably critical and concerned about the PPB, yet still talk about the need for crime prevention, enforcement and improved public safety.

I saw part of the Hardesty/Gonzalez debate, and I thought HArdesty did a good job calling out PPB for this. The question was about a WW report about open drug dealing at Dawson Park and the high gun violence the park is seeing. She said if reporters can spot and record these drug dealers, so can PPB- drug dealing is a crime- why is PPB not arresting these people?

That sounds like profiling.

Jonathan you believe the intent of the police is to make the city worse–strong claim–do you have any evidence?

Yeah, until a person driving 25 MPH in a 20 zone can actually expect to receive a speeding ticket, this is all meaningless safety theater.

Why is that? If they were previously driving 30 MPH in a 25 zone, that’s an improvement.

We all know enforcement is low, but not non-existent and some combination of the slim possibility of enforcement, courtesy, or peer pressure seems to cause drivers to lower their speed when the speed limit changes. So it’s not “safety theater”.

Definitely could be better.

This study suggests that if they were previously driving 30MPH in a 25 zone, then they’re now driving 29.4 in a 20 zone.

Also an improvement, but not really.

Of course I’m no statistician but my own unscientific observations that in my neighborhood where the speeds have been lowered there’s very few people going that speed. Routinely people get upset behind me when I’m going the speed limit. Then the observations being a pedestrian and watching drivers zoom by well above the 20 mph doesn’t jive with these findings.

I wonder did they purposely cherry pick data from an area(s) where they already knew what the outcome would be?

There’s a link to the study, which has a map of locations.

Paint is better protection than signs are traffic calming.

We are in the third decade of smartphones. Every street is a through street now, and diversion by default is the only way to funnel traffic back onto a manageable set of collectors and arterials instead of everybody coming from everywhere at the speed of their choosing.

Paintsigns are not protection. This is just a waste of time and performative at best. They’ve made N Willamette worse for law-abiding motorists. The road is still designed for motorists to go 40mph+ so now I get tailgated by angry motorist most of the time I drive down it. Not to mention the huge uptick in people utilizing theauxilery drivingbike lane to pass law-abiding motorists or motorists making a left turn.Beg barrrels and beg signs are not infrastructure.

Reducing speed limits and then achieving compliance thru engineering or enforcement is a chicken and egg problem. You can’t get engineers to calm a street (or cameras or police to enforce) unless observed speeds are greatly in excess of posted. So these lower speed postings SHOULD set the stage for more improvements. The worst scenario would be no engineering or enforcement follow up, and it becomes “normal“ to drive even more in excess of the posted speed. Avoiding that will require a lot of pushing.

No, the worst scenario was proven in Medford recently. An automated red light camera was proven in a court of law to have been intentionally programmed to illegally trap thousands of unsuspecting motorists into outrageous automated fines. Now that automated enforcement is a PROVEN revenue enhancement vector, angry motorists will respond as always.

Obviously completely speculative, but I’d be more than willing to bet that a fair share of those receiving automated tickets for speeding or other violations are among the same group of people who complain about others breaking various laws. Why should our dependency on cars provide special license (pun intended) to break any law about driving ad lib? If you’re not violating speed limits–which are laws, after all–why should you be worried about automated enforcement?

If police ever enforce traffic crimes again, having a lower speed limit will mean that they will write tickets for less fast speeds.

Lisa, you seem to be implying that previous coverage was misleading, but WW correctly cited the 2020 study’s findings to my mind:

That finding is consistent with what Dr. Anderson presented. The change in average speed was never said to be significantly different, the drop in speeding rates (instances of 15+ mph over the limit) was.

That actually makes sense to me. It’s about the shape of speed distributions: if the vast majority of people drive at about the speed your program hopes to achieve, the mean might not be the best way to describe a change in that distribution. Maybe we’re not trying to shift the whole curve, we’re trying to lop off its tail.

Note that while you assumed the baseline average was 25mph in your percentage calculations, the pre-program average was actually about 22 mph. Given that most people were already driving at essentially a vision-zero-approved speed, is a change in mean speeds the best way to describe program efficacy? I would argue no.

My issue with what Dr. Anderson presented is that we only got complete model coefficient results for his log-linear models, which were not the focus of PBOT’s PR run. I would’ve way preferred to see error & significance estimates for his binary models, which tested whether the program effectively reduced the incidence of top-end speeding. He just gave us a bar plot, with no info about additional covariates or margins of error.

Thank you for your comment, bbcc. Anderson presented data from two separate studies, one for local streets (20 is plenty) and a 2nd for collectors and arterials, the newly presented data. (Try refreshing your screen, earlier today I clarified the label on the three slides from the talk).

You seem to be referring to the first study in your comment, I agree that the first study was fine (with the caveat that results are obviously limited to the time period studied—a novelty effect could wear off).

The second study was on the bigger roads, and had the end points during the pandemic. So not a covariate problem, just a big unfortunate circumstance that wasn’t corrected for.

Heres a “linear model” to consider. Some Wyodak powered green lies called Tesla can go from dead stop to 60 mph in under 4 seconds.

Consider BS taken to such glorious technological heights and pay attention to your surroundings.

My reaction to the headline: “And water is wet.” But it’s not because Vision Zero policies are bad per se – just the way PBOT and the city of Portland has executed on that. There seems to be no political will to do the right thing when it stares you in the face because it might upset someone behind the wheel.

Why waste effort deconstructing “Vision Zero?”

First, anyone who knows anything about the mathematics governing traffic crashes, the statistics of infrequent events, knows that one never can get to zero, only approach it as asymptote. VZ was a gross misrepresentation of reality from its beginning.

Second, it was based on a greatly restricted data set, 10 years or so of deadly crashes in Sweden. I took a hard look at that data and concluded that it had been severely manipulated, for 3 of the years had numbers that were nearly the same, within a few percent. Certainly not realistic.

Third, if one needed the best data set, one would have used that from the US, which goes back farthest and is the world’s largest, by far. But that would not have produced the preferred result.

The self-promoting airhead dingbats who headlined VZ cherry-picked particularly bad data and transposed it to promote their career goals. Many smart and dedicated people bought into it, because it comported with their ideals.

VZ was a fraud from the beginning. Get real.

The speed limits are great, they calm down the street for sure, but from all that I’ve seen the welcome additions like diverters, etc are doing little to achieve the stated goal of the Vision Zero program.

Seems like all the efforts to limit speeds are done on streets that are already pretty calm, instead of streets with two or more car lanes in one direction, where most accidents happen. For example, lots of money spent on calming down SE16th (Buckman neighborhood) but nothing really to slow down cross streets like Belmont. They even took away the turn light on Hawthorne, making it less safe, and effectively increasing the speed for cars on the fast street.

PBOT likes to blame ODOT for most high crash corridors, but will they actually ever try to slow down the strodes where most fatal accidents happen?

great point! When PBOT was doing wrok on Greeley, I asked if they could lower the speed limit. A family in a mini van had recently been killed and high speeds were a factor. PBOT had the speed stats: over 55 in each direction ina 45 mph zone. I was concerend that widening teh lanes to 12′ and 13′ would make the street faster and more dangerosus, or at least was amissed opportunity to use design to slow the traffic. PBOT’s response: This is not Vision Zero project, so those gaols do not apply here (?!). This is being paid for with “freight dollars” so we are accommodating those goals. I also pointed out many deficiencies in their bike route design, whcih they acknowledged and said that they might consider looking at that sometime later in the future, maybe.

My conclusion: PBOT IS NOT focused on safety or Vision Zero,. They are making similar decisions that ODOT is making- 2 sides of the same coin.