(Photo: Jonathan Maus/BikePortland)

After an hour and twenty minutes of public testimony, the Oregon Transportation Commission voted on a funding allocation scenario for the 2024-2027 Statewide Transportation Improvement Program (STIP) Tuesday night. The proposal they moved forward isn’t what nearly every person who testified had asked for, but it showed how a strong progressive voice and an ever-growing transportation reform advocacy coalition are being heard at the highest levels of policymaking.

“OTC, do your job and serve the people in this great state of Oregon… this STIP package should invest as much as possible in non-highway projects.”

— Aimee Okotie-Oyekan, Eugene-Springfield NAACP

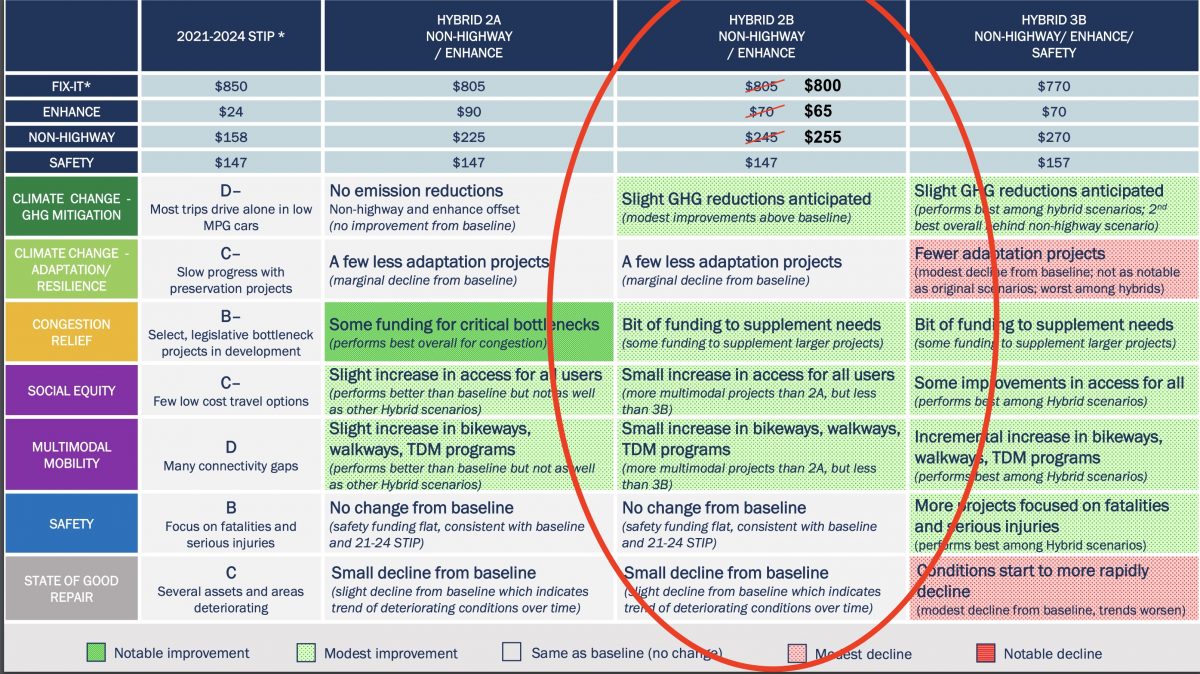

In the end, the five-member OTC directed the Oregon Department of Transportation to set the “non-highway” funding category at its highest level ever — $255 million. That’s a 20% decrease from the $321 million non-highway proposal activists had rallied around for the past few weeks, but over 60% higher from the current STIP non-highway funding level of $158 million.

When ODOT first revealed the funding scenarios, one of them included a 103% increase to the “non-highway” funding category compared to the current STIP (2021-2024) — an increase of $163 million (from $158 to $321 million). Dubbed the “Non-Highway” scenario, it performed better on climate change and greenhouse gas emission reduction measures than any other proposal and was supported by many advisory groups and activists statewide.

Advertisement

But it was almost too good to be true. Just days before the OTC was set to vote on the scenarios (December 1st), ODOT staff (in coordination with OTC members) introduced several new scenarios that significantly decreased non-highway funding and put more money toward the “Fix-it” category which focuses on driving-centric highway paving and maintenance. Instead of $321 million for non-highway, a new “hybrid” scenario offered $225 million.

“Stop using maintenance as an excuse for perpetually short-changing the important investments in safety and climate justice that need to be done with urgency.”

— Sarah Iannarone, progressive activist

The shift toward more spending on bicycling and walking projects in the STIP was spurred by the executive order on climate change issued by Oregon Governor Kate Brown earlier this year; but it was pushed toward the finish line by Oregonians off all stripes who were organized by activists to make their voices heard.

Among the people who testified in favor of more non-highway spending last night were Portland mayoral candidate Sarah Iannarone and Multnomah County Commissioner Jessica Vega Pederson (who also spoke on behalf of Portland Bureau of Transportation Director Chris Warner).

“Stop using maintenance as an excuse for perpetually short-changing the important investments in safety and climate justice that need to be done with urgency,” Iannarone testified. “ODOT staff needs to stop presenting my community with the false choice between road maintenance, traffic safety and climate action and you need to stop enabling them. Freeway expansion is not economic recovery.”

Commissioner Pederson said Multnomah County and the City of Portland supported the original non-highway scenario and that, “A significant and sustained commitment to investing in projects that reduce carbon emissions, increase safety and decrease transportation inequities.”

RJ Sheperd with Bike Loud PDX told OTC members that Oregon can save money and lives by investing more in bikeways and walkways. “Every $1 million spent on active transportation creates four more jobs than highway expansion,” he said.

Advertisement

For Aimee Okotie-Oyekan, who serves as the environmental and climate justice coordinator for the Eugene chapter of the NAACP, the STIP is a chance to right past wrongs.”We know that people of color are consistently exposed to more air pollution and highways have historically been built in black and brown communities to displace them,” she shared in her testimony, “OTC, do your job and serve the people in this great state of Oregon… this STIP package should invest as much as possible in non-highway projects.”

Portlander Michelle DuBarry’s one-year-old son was killed while walking across North Lombard Street in 2010. “Every day I think about simple infrastructure changes that might have saved my son,” she shared. “And I wonder why ODOT continues to prioritize cars in the face of the twin crises of pedestrian fatalities and climate change.”

Advertisement

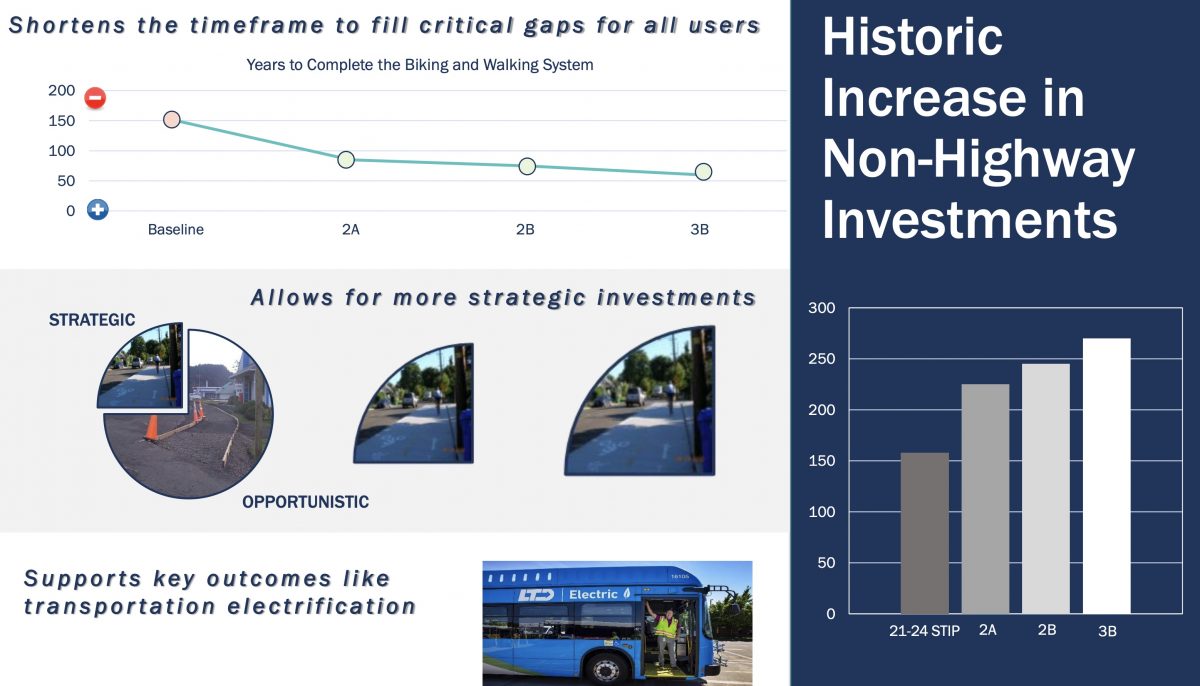

After hearing these urgent and cogent demands for more non-highway spending, OTC members heard from ODOT staff. They said whatever scenario was chosen would be a “historic increase” for biking and walking. One slide showed that if ODOT maintained the status quo it would take 150 years to complete the statewide biking and walking system, whereas new funding proposals would drop that timeframe to “just” 60 years. Staff also painted a picture of dire need for pavement repair and maintenance of major roads and highways. “These scenarios are about trade-offs,” said ODOT Delivery and Operations Division Administrator Karen Rowe, “I hope this information helps convey the challenge to keeping the roads and bridges in a state of good repair.”

When it came time for commissioners to deliberate and choose an option, Chair Robert Van Brocklin claimed poverty. He tried to make the case that there just isn’t enough money to do everything people ask of ODOT. He said ODOT’s hands are tied by legal mandates that earmark much of the agency’s funding. “The courts, the legislature, and the governor’s executive order [on climate change] are all placing obligations on the agency to build all of these things… we just don’t have the money.”

Van Brocklin was referring to “things” like federal laws that require ADA ramps, the Oregon legislature’s requirement of a new tolling program (which he thinks will cost “hundreds of millions” to implement), and the 2017 transportation package that earmarked hundreds of millions for the I-5 Rose Quarter, I-217, and Abernethy Bridge megaprojects. “I listened to the public talking about our discretion,” Van Brocklin said. “We don’t have discretion. We’re implementing those decisions.”

Advertisement

For several minutes OTC members played with the funding splits, shifting tens of millions of dollars around in a way that didn’t cause too much heartburn for any one of them. In the end a motion was made to support scenario “Hybrid 2B” which funded the categories at $805 million for Fix-it, $70 million for Enhance, $245 for Non-Highway and $147 for Fix-it. But OTC Vice Chair Alando Simpson said he wouldn’t support that option because he preferred the “optics” of pushing for more non-highway spending. Simpson said he’d support $795 million for Fix-it and $255 for non-highway.

Van Brocklin clearly wanted a unanimous decision and had voiced earlier that despite all the testimony he just couldn’t fathom the thought of taking Fix-it below $805. “I would like to keep Fix-it at at least $800 [million],” he said. “I think about the fires, I think about the earthquake, I just think about all kinds of things that require us to have a functioning highway system.”

He proposed a compromise split of $800/$65/$255/$147 that Simpson went along with and was ultimately voted on by all five commissioners.

Simpson said the decision, “Opened up a new door for for the state of Oregon in terms of how we really value investments and how we perceive the transportation system and its impact on people’s lives in the broader community.”

Even with record spending on non-highway projects, OTC members knew this wasn’t the big and bold step many hoped for. “We are concerned about the issues you raised, we understand they’re out there,” Van Brocklin shared in his final remarks that were directed at the many people who testified just two hours earlier. “We have to find more resources.”

— Jonathan Maus: (503) 706-8804, @jonathan_maus on Twitter and jonathan@bikeportland.org

— Get our headlines delivered to your inbox.

— Support this independent community media outlet with a one-time contribution or monthly subscription.

Thanks for reading.

BikePortland has served this community with independent community journalism since 2005. We rely on subscriptions from readers like you to survive. Your financial support is vital in keeping this valuable resource alive and well.

Please subscribe today to strengthen and expand our work.

STIP – The Game

– Agree to a soul-destroying slimy backroom deal, move forward 3 spaces and collect $6 million.

– Get your project approved by PBOT for the TSP, move forward one space.

– Supported the wrong candidate, move backwards 2 spaces.

– Successfully named your project after a living statewide elected official, move forward 2 spaces and collect $2 million.

– The feds sequestered your funding, lose one turn.

– Successfully got local jurisdictions to sign off on EIS, move forward 6 spaces.

– Subject of major riot, move back 5 spaces, lose turn, but collect $10 million.

wow, thanks for shinning the light on how these decisions are made. So little thought, all about “perception”, haphazard, very little accountability. I am so tired of ODOT. How do we change this dinosaur of an institution?

You talk to the governor and your state senator and representative.

Petition advocacy groups to contact politicians. Give advocacy groups money. ODOT won’t change from within. It is very malleable from influence from above. State Representatives and Senators tell the Agency what to do. National Reps and Senators influence all levels of state government. Hipsters with man-buns shouting and carrying signs don’t carry influence. Or get a job in the Agency and change the zeitgeist from within. They are always hiring

Does anyone have recommendations for advocacy groups to support that oppose the I5 Rose Quarter expansion? I’m wondering how best to help get word out about the negatives of the project to Oregonians.

Given that Portland signed off on the EIS when the governor and state legislature wanted them to (and deliberately tried to back out in time for an election when they knew it was far too late), the only powers that can stop this project are your governor and state legislature (even the president has no say so.) I’d start with 1000 Friends of Oregon. https://friends.org/

“How do we change this dinosaur of an institution?”

Stop supporting and voting for automobile- and highway-loving corporate fascist democrats (e.g. Kate Brown).

ODOT makes a compelling case: they cannot afford to maintain what they have an make investments that address climate change and support safe alternative transportation. Time to cancel the highway expansion at the Rose Quarter and pare back the 205 expansion to just seismic improvements and no new lanes!

Urban triage: Abandon all Orphan Highways not yet funded, let them crumble – if cities want them, give them away “as is”.

Not sure if you’re being sarcastic or not here, but I actually would agree with it. If PBOT wants the roads a certain way after a jurisdictional transfer, it should be PBOT’s job to implement those improvements, not ODOT’s. I agree that what PBOT wants to do to them is a good idea, but it’s their responsibility and to me it seems that they’re the ones being unreasonable by demanding that ODOT make the changes and then immediately transfer them.

The orphan highways have been deliberately neglected for decades. ODOT has no intention of ever fixing them. These are roads where people in our community die at a frequent rate. If you were PBOT, would you take on 82nd Avenue knowing it is going to take $300-400 million just to bring it into a state of good repair? PBOT doesn’t have that kind of money. Hence the reasonable request for the state to make up for its decades of deliberate neglect before a transfer.

Based on the upvotes of our respective comments, looks like opinion here is split on the issue 🙂

I don’t know of any states that have successfully foisted crumbling urban highways onto local jurisdictions without investing some reasonable amount in fixing them up before the transfer. If they tried, there would be massive lawsuits. I used to think Washington state had done this, but it turns out they somehow transferred “road authority” to the local jurisdictions while keeping the maintenance liability with the state. That could be an interesting way to deal with this conundrum. But it would still be a difficult arrangement.

I think you are correct, Oregon would likely be the first if they did so, but given the its state legislative history of not spending any non-highway money on fixing highways (unlike the other 49) and insisting that only automotive-generated funding can be used towards fixing stroads (again unique among the 50 states), I can easily see it happening. By deliberately neglecting these stroads, the state is already effectively doing it.

The other option, which happened in NC, VA, and WV in the 30s, is for the state DOT to forcibly take over all the county DOTs and all streets of collector level and over, as well as the funding allocations from gas tax and other sources. Imagine NW 23rd as an ODOT road.

More Sarah quotes

It seems that my sleepy emoticon didn’t show up, lol. 🙂

you serious? Because I would gladly do that. She is a really good testifier. Her comments yesterday were on-point and well-delivered IMO.

Anyone know how “non-highway” is defined? I would hope, for example, that building a walking path over a highway (that is needed because the highway splits the community in half) is part of the highway budget, not considered pedestrian infrastructure.

Nope, that’s “non-highway”, and so is the funding to rebuild the segments of the Historic Columbia River highway which were destroyed when ODOT built I-84, since they will be mostly useful for bikes and walking, ignoring the fact that the historic highway would have been perfect if left intact or replaced when the freeway was built.

Per the hypothetical sidewalk on the bridge: If an existing portion of travel lanes were taken away to build the sidewalk on an already existing road bridge, it most likely would be in either the Fix-It or Non-Highway fund. If the sidewalk is attached as an extension of an existing bridge, it most likely would be an Enhancement to the existing structure. If we were building a brand new bike/ped bridge over a minor orphan highway highway, most likely it would get cancelled or delayed by 25 years. If on the other hand we were building the same bike/ped bridge over a major freeway or trunk road (US 101 or US97 for example), it would likely be funded either as Non-Highway, Highway, MTIP, or even as a pork-barrel earmark depending if it was called for in the original highway plans of 1956/1965/1971/etc or if it was in response to very recent advocacy in the last two decades.

Via ODOT:

“Non-highway programs fund bicycle and pedestrian projects and public transportation.”

“ Fix-It programs fund projects that fix or preserve the state’s transportation system, including bridges, pavement, culverts, traffic signals, and others. ODOT uses data about the conditions of assets to choose the highest priority projects. In recent STIPs, the Commission has allocated most funding to Fix-It programs.”

Most complex projects like outer Powell are a mix of Fix-It, Enhanced and Non-Highway, as they are different funding silos. The portion of outer Powell that is preserving existing infrastructure (the driving lanes) is Fix-It, but any added right-of-way portions, including the sidewalks and center turn lane which generally don’t exist yet, are “non-highway”, while the cycletracks are “enhanced”, an upgrade of the existing bike lanes. “Highway” usually refers to trunk roads like the freeways, US 101, and US 97, but not Powell, Lombard, Barbur, etc, which are “non-highway” or fix-it depending on what’s being done to them. The expansions of I-5 and I-205 are most likely a mix of “Highway” and “Enhanced”.

Why can’t we call them what they actually are: roads, sidewalks and bike paths?

Again, many thanks for this coverage, and thanks to those who testified!

Sounds like all these categories are designed to be as vague and fungible as possible, so that in the end, ODOT does whatever they wanted to do anyway. The public is left clueless in the back seat, madly spinning a toy steering wheel.

Not enough.

Not nearly enough to halve emissions by 2030.

That is the only goal that matters.

Hey, speaking of changing projects and/or allocating additional funding to Non-Highway projects in the name of Gov. Brown’s executive order, is it too late to retool the SW Corridor to be one driving lane in each direction the entire length of Barbur Blvd? We know this thing is going to be brought back to life, and it’s a worthwhile project on the whole. But keeping two driving lanes each direction makes no sense, and it’s now not in compliance with the Executive Order to reduce GHG emissions. With a scope reduction, it should cost significantly less with that much less right-of-way to acquire, and actively reduce driving by slimming down Barbur (the way they did with the MAX line on Interstate–literally the same road, 99W). What, if anything, can be done about that?