(Photo: Jonathan Maus/BikePortland)

“A large number of people talked about focusing on reducing greenhouse gas emissions.”

— Excerpt from ODOT STIP Public Input Summary

At their meeting on December 1st the unelected leaders of the Oregon Transportation Commission (OTC) will decide which direction to steer the Oregon Department of Transportation (ODOT) when it comes to spending $2.24 billion. It’s the first major decision point in development of the all-powerful 2024-2027 Statewide Transportation Improvement Program. Known as the “STIP”, it’s Oregon’s master list of infrastructure projects.

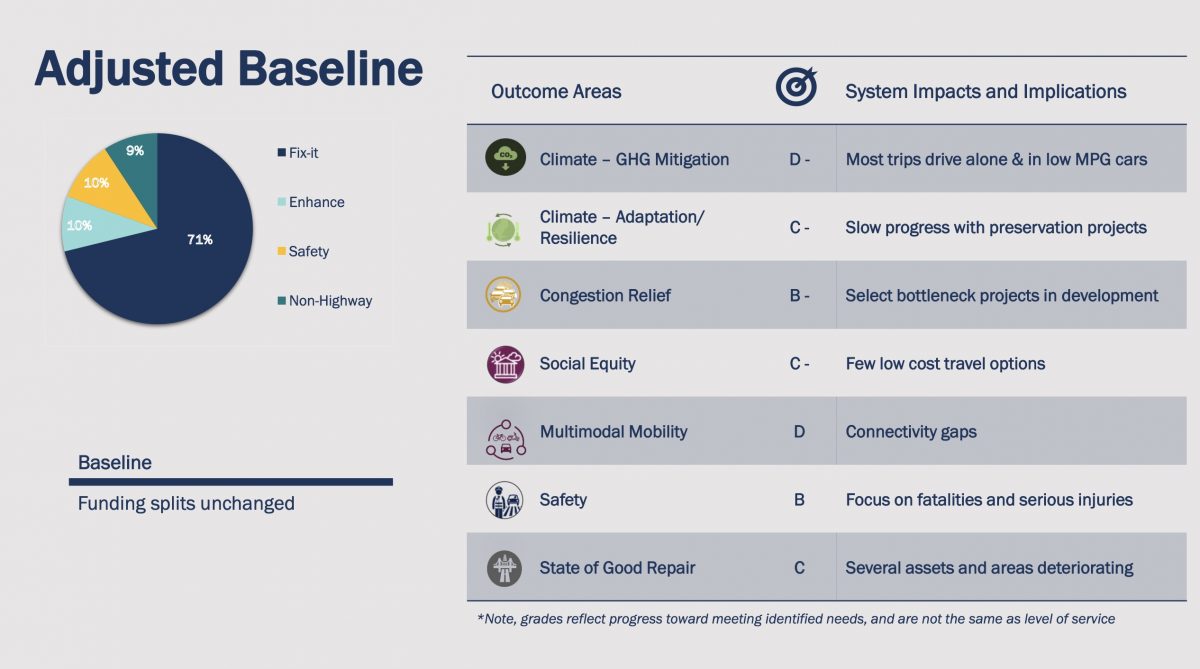

Left to their own devices, ODOT and statewide politicians are likely to invest our transportation dollars in a way that favors the status quo of driving. In fact, in a meeting of the Oregon Bicycle and Pedestrian Advisory Committee on November 18, an ODOT staffer revealed that if stay on the same funding path as the current STIP, it would take 150 years to build out Oregon’s network of bicycle and pedestrian projects.

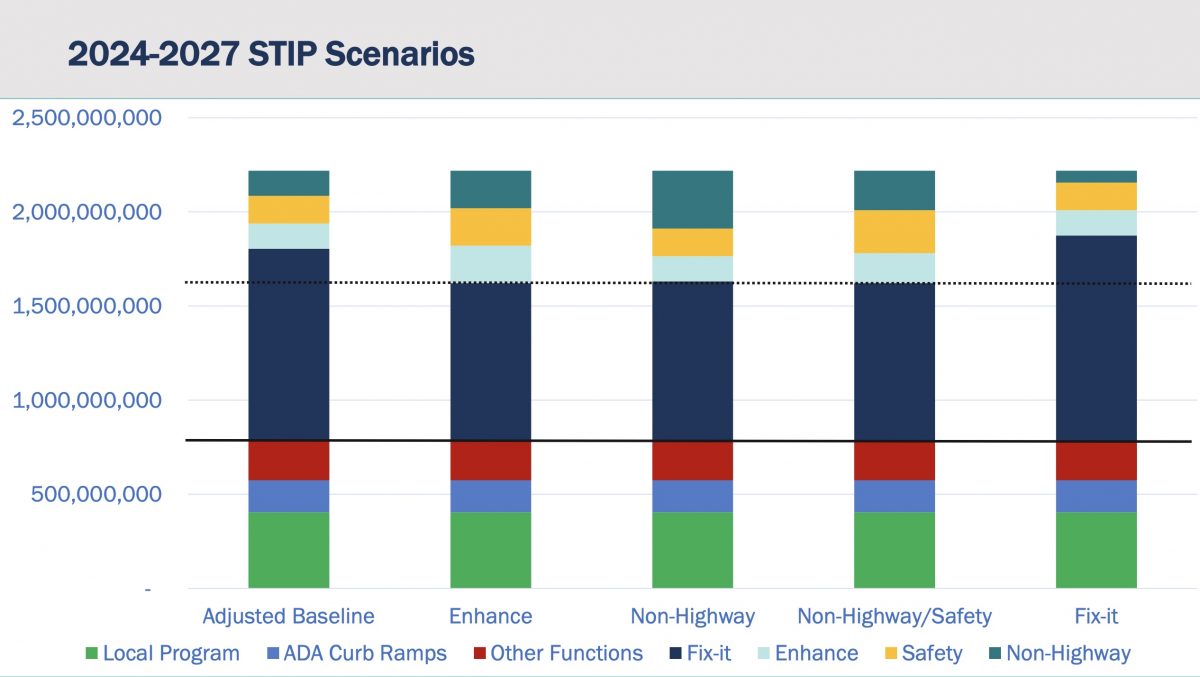

But now isn’t the time to talk about specific projects. At this early stage in the STIP game it’s all about what funding categories will get the most attention. ODOT has broken down the funding pots into four main categories: Enhance (“Highway projects that expand or enhance the transportation system”), Fix-it (“Projects that maintain or fix the state highway system”), Non-Highway (“Bicycle, pedestrian, public transportation and transportation options projects & programs”), and Safety (“Projects focused on reducing fatal and serious injury crashes on Oregon’s roads”).

(Aside: These arbitrary categories and official definitions have lots of blurred lines and biases baked into them. An “enhancement” to one person might be a detriment to someone else. And “highway projects” can include significant amounts of bicycling and walking infrastructure. And let’s remember that “highways” aren’t always interstate freeways, many of them are roads that run through neighborhoods and main streets.)

Advertisement

ODOT has taken these funding categories and created five “scenarios” to help illustrate impacts to various agency goals and other tradeoffs that come with funding one category more or less than another. The scenarios are: Adjusted Baseline (keep things basically the same), Enhance, Non-Highway, Non-Highway/Safety, and Fix-it (see above). At their December meeting OTC members will choose which scenario to go forward with, thus setting into motion which type of projects are more likely to see some of that $2.24 billion.

In the past few months, government agencies, advocacy groups and activists of all stripes have sent in comments and letters to the OTC hoping to influence their decision.

Looming especially large this year is a focus on how investments will impact climate change. Back in March Oregon Governor Brown issued a executive order directing state agencies to reduce greenhouse emissions. She had specific marching orders for ODOT to, “develop and apply a process for evaluating the GHG implications of transportation projects in the STIP.” This has led to ODOT applying a “climate lens” to the STIP process for the first time ever. And as we shared last month, ODOT’s new climate office is already on the case.

To evaluate the different funding scenarios, ODOT created a matrix of rankings based on seven different outcomes — two of which related directly to climate change.

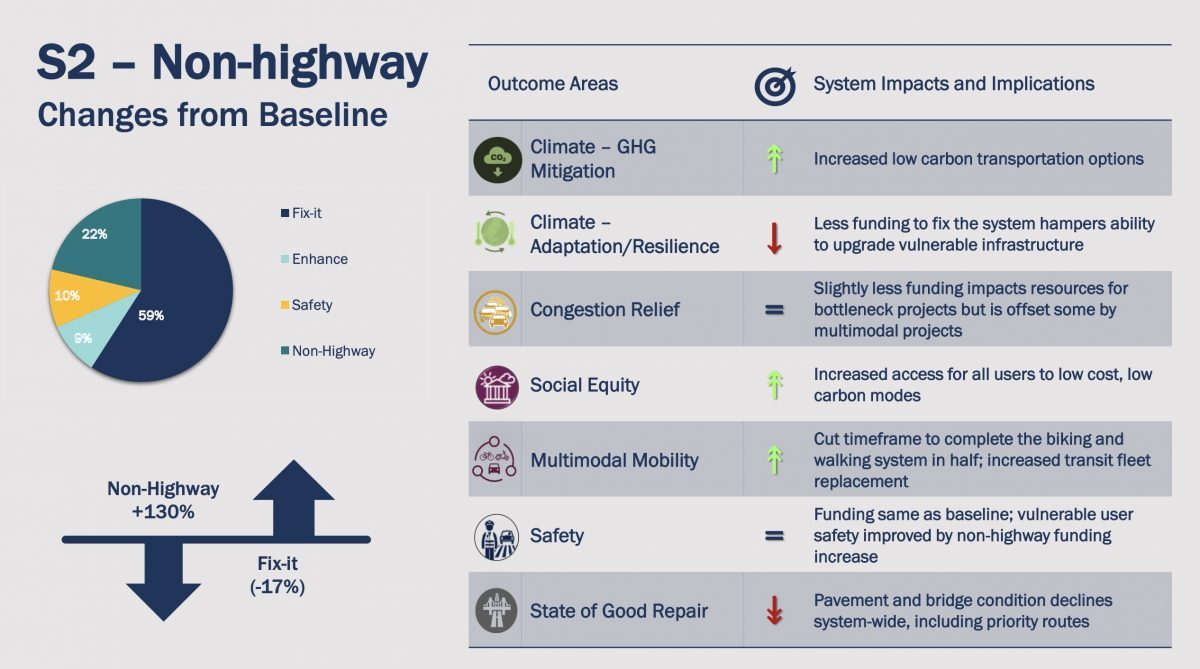

Several government agencies and advocates are pushing the OTC to adopt the “Non-Highway” scenario because it has the greatest positive impact on GHG reduction and climate resiliency.

A letter to the OTC from a coalition of transportation reform and social justice groups including Bike Loud PDX and the Oregon Environmental Council said, “The ‘Non-Highway’ scenario provides the most investment in the parts of our transportation system that provide the most positive effects on equity, air quality and climate pollution. The more people who are able to bike, walk and take transit, the more efficiently we can use our right-of-way while also reducing air toxics and greenhouse gas pollution and providing more freedom and access for people who do not or cannot drive. Also, non-highway projects provide more jobs per dollar spent than road-building projects.”

According to ODOT analysis, in the Non-Highway scenario, “the substantial increase in funding to [the non-highway category] cuts the timeframe to complete the bike-ped system in half.”

Advertisement

Mavis Hartz is a member of the La Grande School Board and chair of ODOT’s Safe Routes to School Advisory Committee. In her letter she implored the OTC to make a dent in the estimated $1 billion in projects within a one-mile radius of Oregon schools. “Being able to walk, take transit and bike to parks, stores, and places of employment is key to achieving Oregon’s climate goals,” she wrote.

The City of Milwaukie, led by its climate change-centric Mayor Mark Gamba, wrote that, “While none of the funding scenarios fully meet the needs of both adapting the system for climate resiliency and providing greater access to low carbon travel options, the city believes the non-highway option provides the greatest flexibility and tools to do so.” The Lane Area Commission on Transportation, an advisory group set up by ODOT to represent Eugene/Springfield and other cities in Lane County, also supports the Non-Highway funding scenario.

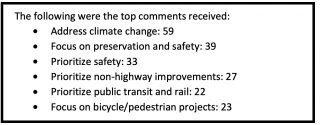

ODOT’s own public outreach showed broad support for investing in a way that tackles climate change. In a public input summary report made available to OTC members this week, ODOT wrote that out of all respondents to their online open house, “A large number of people talked about focusing on reducing greenhouse gas emissions as well as fixing the infrastructure we already have.” Of all the comments received, “address climate change” was the top-ranking subject.

Of course not everyone is on board with the Non-Highway scenario. Clackamas County supports thinks the “Enhance” scenario “strikes the right balance.”

The OTC, which is intended to be independent of ODOT but in reality is often their biggest cheerleader and a reliable rubber-stamp for whatever agency staff wants, is likely to talk about balance a lot at their meeting in December. If you want to help tip the scale, you can still comment directly to OTC members through December 1st.

This is the first step of the three-part STIP process. After funding allocations are decided it will be time to pick specific projects. The project list will then be up for public review and final approval by early 2023. Stay tuned to BikePortland and Learn more at ODOT’s website.

— Jonathan Maus: (503) 706-8804, @jonathan_maus on Twitter and jonathan@bikeportland.org

— Get our headlines delivered to your inbox.

— Support this independent community media outlet with a one-time contribution or monthly subscription.

Thanks for reading.

BikePortland has served this community with independent community journalism since 2005. We rely on subscriptions from readers like you to survive. Your financial support is vital in keeping this valuable resource alive and well.

Please subscribe today to strengthen and expand our work.

And, while not posted yet – readers will be able to access a video recording of the Region 1 ACT’s special meeting from last night (11/24/20) here https://www.oregon.gov/odot/Get-Involved/Pages/ACT-R1.aspx Worthwhile if you want to hear what Portland Metro elected officials are thinking and talking about.

In DOT-speak, the word “enhance” usually means “to widen the roadway, the right-of-way, and/or to add additional new facilities such as bike paths, sidewalks, tourist info centers, or rest areas.” The word “preservation” usually means “to maintain a road surface by grinding and repaving and/or rebuild the base materials for a roadway.” The word “safety” always refers “to car driver crash prevention, using smoother pavement, guardrails, wider lanes, and other very expensive physical improvements”, but never speed limits, traffic calming devices, nor enforcement. In general, a “highway” IS a freeway, while a “non-highway” is a main street, stroad, or other roadway owned by the state, including a lot of designated state and federal highways, but it depends on where you live – US 101 along the coast is also a “highway” as is US 97; it’s what the British and Canadians call a “trunk road”, the main road that all other roads branch off from.

We are doing the same process locally here in Greensboro NC right now – my response letter on behalf of others is due on Dec 1st. I find it easiest to find the projected revenue for a certain period and then modify the funding scenarios to match our criteria for meeting climate goals – since highway engineers have all kinds of arbitrary assumptions built into their models, there no reason the rest of us can’t do it too.

For example, my community expects to have just under $5 Billion available over the next 25 years (to 2045), in today’s money, roughly $200 million/year. They also made a commitment 20 years ago to spend $1 Billion on a completely unnecessary full bypass around the city, now nearly completed, so I know they are capable of spending a lot of money long-term for a common goal. The current funding formula here is 90% for roadway projects statewide and 80% for roads locally; 5% for rail and transit statewide and 15% locally; and no more than 5% statewide and locally for bike/ped. So my assumptions are:

– California will be a driving force nationally on gas taxes, the conversion towards electric cars and car-share, and the end of sales of gas-powered vehicles – every state, including NC and Oregon and the cities thereof, will need to impose user fees or else go bankrupt surviving on gas taxes and taxes on car sales.

– There will be a rapid rise in extreme temperatures and worse storms. Locally here in NC, the past 4 years we’ve been 20″ above normal on our rainfall, usually from intense storms followed by prolonged 30-45 day droughts. Our summers have gotten hotter (it’s already a hot humid climate.) Yet people keep moving here and our population keeps growing, especially more retirees (NC is the discount Florida), immigrants & refugees, and migrant industrial workers.

– There will be a radical shift in our politics whereby conservative Republicans (currently the majority in both NC legislative chambers, but not the governor) will champion transit, bike, and ped projects for rural tourism and economic development, helping the aged, and more jobs for suburban whites (the backbone of their supporters), reversing funding to only 10% for highways and 90% for all other modes.

Let’s see, 90% of $5 billion is…hmm…

Hopefully NC doesn’t have a constitutional ammendment requring gas taxes be used on car/highway projects or an initiative process that voters can use to cut car tabs and fees.

You know, it occurs to me that this problem is going to solve itself. In a decade, there will be fewer gasoline vehicles, and in two decades far fewer. Fuel taxes are going to go away, and the constitutional restriction on their use along with them.

Keep in mind that — right now anyway — toll revenue and other auto fees are considered to be under the constitutional restriction. (Considered by the OTC, ODOT, legislators)

Only Oregon and the Feds actually require gas taxes to be used on transportation infrastructure projects. In all other states, its another useful source of revenue, but I’ve seen gas taxes used for schools and prisons here in NC and in other states, as well as for transit operations. NC is the only state that I’ve ever lived in that doesn’t allow initiatives of any sort (the US Constitution never specifically mentions them either.)

I love that the “non-highway” mix of funding features mostly highway spending. The word “enhance” has a very positive connotation–why isn’t multimodal transportation considered the “enhance” option and highway spending called the “new and wider roads” option? The language is certainly misleading.

I’m looking forward to their replacing the word “iterative” with “organic” (a common transportation planning and engineering process of making constant adjustments as users react to changes, rather than following a set plan); “asphalt” paving with “organic hydrocarbons”; and “automobiles” with “freerange macromobility units.”

Seems Gov Brown’s executive order should have first directed ODOT to review all not yet completed projects with a climate lens

The vast majority of Americans, including probably your governor and legislature and both presidents, firmly believe that an idling automobile is a major climate threat that needs to be curtailed at all costs, and so they honestly see the Rose Quarter freeway expansion project, or any highway expansion project for that matter, as being completely positive on preventing, or at least mitigating, climate change. Moreover they are completely unaware that concrete production and use is a major contributor to greenhouse gasses, even more so than asphalt.

Screw the bicyclists they were given bike lanes all over the city. Now they want all tge streets. Start charging road taxs yearly to bicyclists.

Would you support an annual vehicle tax (that somehow included bikes) based on vehicle weight and mileage (and, hence, damage done to the streets)?

“Start charging road taxs yearly to bicyclists.”

Wow, you obviously haven’t researched who REALLY pays more for roads. Hint: It’s not drivers.

Who really pays more for roads than road users themselves? Please show your math.

Thanks, JM, for covering this important story. Most people – me included – remain blissfully (?) unaware of how our state transportation $$ are allocated. We mostly go outside and try to ride our bikes and say to ourselves, This road sucks. And we never return, or we drive everywhere. People seem to carry around a fatalistic view that our roads are the way they are b/c they have to be that way.

Centrist nonprofits like BikeLoudPDX, the Oregon Environmental Council, and OPAL Environmental Justice would have us choose between ODOT plan 1 vs ODOT plan 4 but all of these utterly fail to address the magnitude of the climate crisis. The nonprofit leadership in these organizations may have the luxury of time but many in the global south do not.

Is our house burning down or not?

So we get good bike infrastructure in 75 years if ODOT sways strongly in that direction? How is this NOT admitting failure?

Left a quick comment for OTC – (feel free to pilfer or modify if you want)

“In the next iteration of statewide projects and funding, ODOT (and OTC) must prioritize climate above all else. Transport emissions make up such a significant chunk of total GHG emissions that it would be criminal not to.

I want to know why none of the STIP alternatives adequately funds rail generally, nor high speed rail, nor rail electrification and decarbonization.

I’m strongly opposed to additional freeway funding. You cannot use the excuse that the driving public is switching to electric vehicles, because a) these would still be less efficient (and use more electricity from coal or gas) than electric mass transport including bus rapid transport and rail, and b) you know very well that the electrification of the motor fleet is not happening at the necessary speed (especially when you factor in that the average fossil fuel powered car today will likely still be on the road in 15-20 years).”

“I want to know why none of the STIP alternatives adequately funds rail generally, nor high speed rail, nor rail electrification and decarbonization.”

I don’t know the reason Oregon doesn’t address it adequately, but I can tell you generally why rail is typically ignored by state DOTs (and most cities).

The first reason is that STIP funding only goes state-owned facilities – most railroads in most states are privately owned (for example by BNSF, UP, and a bunch of small ‘short-line’ operators in Oregon.) NC and Virginia are two of the very few states that actually own some of their tracks, while the Feds own the Amtrak main line between NYC and Boston, some nearby branch lines, and a couple small rail switching yards – otherwise they “rent” access from commercial railroads based on a tariff of how valuable a load is per weight-mile (humans are #2, after FedEx and UPS.)

Secondly, the politics of funding railroad (and waterway shipping) improvements is severely complicated, but it has a lot to do with railroads being formed in the 1840s, given lots of land and nationwide privileges by the feds as a bribe to build out west, and if the railroad got land before the state was formed. States are reluctant to fund what are essentially private monopolies that they have no control over and never will have control over (it’s been tried.)

Thirdly, for most states, creating a new railroad is cost-prohibitive, as land has to be bought, construction is very expensive, and on top of every other complication, the private railroads will be opposing the project every step of the way, and they know how your state works better than ODOT does. (However, some states are nevertheless working to create their own rail networks, often buying and upgrading local short-line railroads. There’s also a brand new line being planned and built between Richmond VA and Raleigh NC, part of the SE High-Speed Corridor.)

Fourthly, highways typically account for around 90% of state DOT budgets, a percentage based on a 1950 formula that everyone has gotten used to, including most politicians in Congress of both parties. You can safely bet that most politicians, industry insiders, highway lobbyists, and such ilk will defend that 90% to the death, as their very livelihoods depend on that continued funding – nor will they let any of that funding go to bike/ped/transit/rail projects without a fight.

Fifthly, and last of my comments, electric rail is already in widespread use throughout the USA, but not quite in the same exact form you likely see in Europe with overhead lines. All diesel engines used by the commercial railroads and by Amtrak convert fuel into direct-current electricity that then run the engines, but the wheels are driven evenly and gradually to not damage the tracks they are on. The days of big-wheeled steam and oil-powered locomotives is long gone, for the very simple reason that such engines destroyed the tracks in stations by the incredible friction and pressure of their wheels. The conversion happened quietly starting in the 1930s through a technical agreement of the various commercial railroads of the USA and Europe (France was all-private back then) and by the 60s such engines were universal. The engine that drives a BNSF train in Portland is more or less the same as that for the TGV in France, it’s just that their power source is different. And most electricity in France is nuclear.