It’s arguably the biggest state-level parking reform law in US history.

Crossposted from Sightline Institute. Senior researcher Michael Andersen is a former news editor at BikePortland.

The movement to prioritize housing for people over storage for cars has reached a new high point in the Pacific Northwest.

In the first action of this kind by any US state, Oregon’s state land use board voted unanimously last week to sharply downsize dozens of local parking mandates on duplexes, triplexes, fourplexes, townhomes, and cottages.

Many cities have reduced or eliminated parking mandates in recent years, including Oregon’s largest city, Portland. (As a result, this new rule won’t directly affect Portland — just its suburbs.)

But Oregon’s rule, which stems from its landmark 2019 legalization of so-called “middle housing” options statewide, is a much more unusual state-level action, affecting 58 jurisdictions simultaneously. And because middle housing will soon be legal throughout those 58 jurisdictions — the vast majority of the state’s urban lots — it’s arguably the biggest state-level parking reform law in US history.

Advertisement

Oregon’s new rules hold mandatory parking ratios at or below one parking space per home

In all cases, property owners will have the option to include as many off-street parking spaces as they feel the project needs. Their projects simply can’t be required to have more than one space per home, even on the largest urban lots.

This new standard applies to areas that are home to 2.5 million Oregonians, or 60 percent of the state’s population.

[Related: How car parking makes housing much more expensive.]

Last week’s vote by the governor-appointed Land Conservation and Development Commission will strike down the current parking mandates in Salem (1.5 per home), Eugene (1 per home), Gresham (2 per home), Hillsboro (1 per home), Beaverton (as many as 1.75 per home), Bend (as many as 2 per home), Medford (1.5 per home), Springfield (as many as 2 per home), and many other cities.

In 22 smaller Oregon cities, those between 10,000 and 25,000 population, duplexes will be legalized on all lots. As part of that, duplexes in those cities will no longer be required to have more than one space per home. Another eight percent of Oregonians live in those cities.

“I think it’s great for Oregonians,” said Sara Wright, transportation program director for the Oregon Environmental Council. “We have limited public and private space; we have increasing population. It’s great to give us more flexibility in the way we build our communities.”

“We can now use that space for more housing, more space for others,” said Timothy Morris of the Springfield Eugene Tenant Association, who sat on a state advisory committee that helped vet the rules. “We can even add entire units of housing where parking spaces would have been.”

Wright and Scott were among a coalition of environmental and housing advocates and professionals from around the state, organized by Sightline, who had urged the state commission to pass such a policy.

Mary Kyle McCurdy, deputy director of the anti-sprawl group 1000 Friends of Oregon and one of the architects of Oregon’s middle housing legislation, sat on both advisory committees and watchdogged the commission process over the last year. She credited various factors, including direct input from middle-housing developers and good research by state staff, for building consensus around the change.

“I think it disproved the notion that some of these parking changes were coming from a Portland perspective,” McCurdy said. “That was not at all the case.”

Advertisement

People should not be required to pay for parking spaces they don’t need

The new rule was approved as part of the Oregon Land Conservation and Development Commission’s deliberation on how to interpret a crucial two-word phrase in the state’s landmark 2019 law that legalized middle housing statewide.

The phrase: “Unreasonable costs.” Under the law, cities are not allowed to subject middle housing to unreasonable cost.

That phrase in the law required the state to define, alongside a “middle housing model code” that cities now have the option of adopting, a “minimum compliance standard” with which all cities will be required to comply or be declared “unreasonable.”

(Among the many other pro-housing aspects of the minimum compliance standard that’ll be applied to larger cities and the Portland metro area: For townhouse projects, a minimum average lot size of no more than 1,500 square feet. Writing in CityLab in July, Emily Hamilton of Mercatus Center persuasively identified two crucial ingredients of effective middle-housing legalization: low parking requirements and small minimum lot sizes.)

To arrive at the new parking standard, state staffers commissioned a study to examine possible costs and lot layouts for new duplexes, triplexes, and fourplexes. It concluded that for such structures “on small lots, even requiring more than one parking space per development creates feasibility issues.”

Separately, drawing on prior research by Sightline, state staffers looked at car ownership rates around Oregon. They found that in every affected city, at least 40 percent of tenant households own one or zero cars.

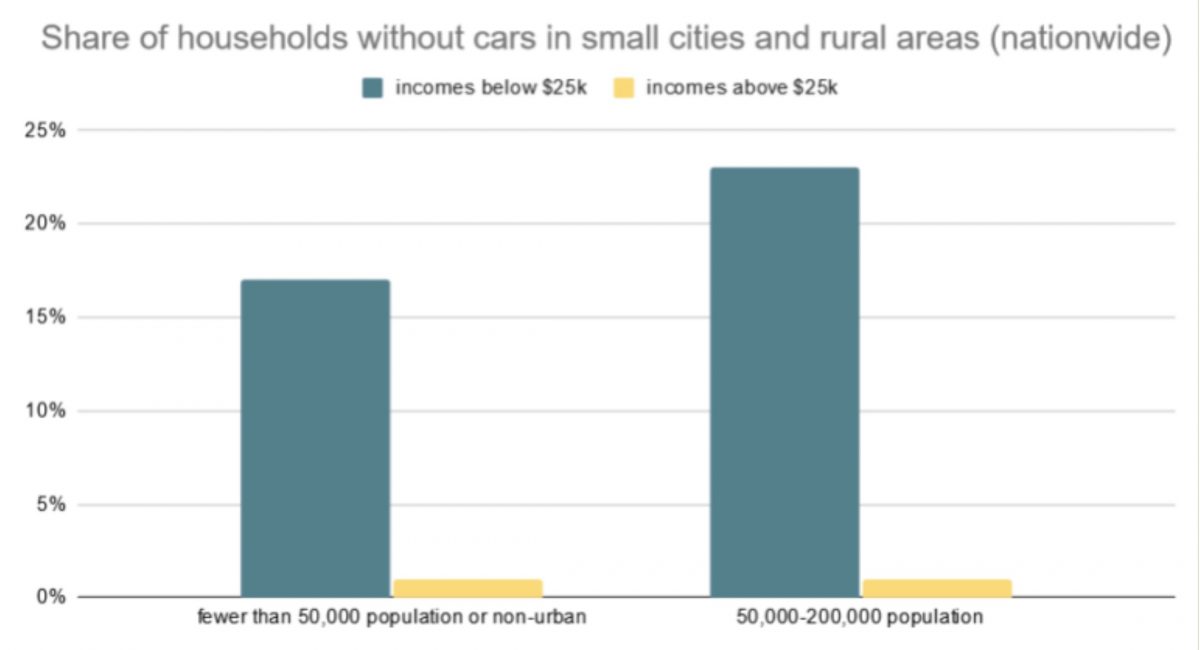

Even in smaller cities and rural areas of the United States, living without a car isn’t all that unusual. It’s simply concentrated among poorer people:

In other words, building lots of off-street parking adds costs that can block projects. And many Oregon households, even in fairly small and rural cities, have little use for it.

Therefore, the staff concluded, it’s unreasonable for a city to require parking spaces whether or not a home’s resident is likely to want them. The reasonable approach is to make it a site-specific decision by the landowner.

The state commission agreed.

Advertisement

A lesson for advocates: Reform parking within the context of things people want, like housing

Fifteen years after Sightline was among the first outlets to call attention to an odd new book by UCLA Professor Donald Shoup, The High Cost of Free Parking, there is now widespread belief among both housing advocates and environmentalists that citywide parking mandates are a bad idea.

If you want to mandate off-street parking, Jordan said, “you’re going to have to cut down trees and you’re going to have to pave more surfaces.”

“One-size-fits-all rules—they don’t take into account a lot of context,” said Tony Jordan, the Portland-based founder of the Parking Reform Network, a national advocacy coalition launched last year that has Shoup, among others, on its advisory board. “They don’t take into account the fact that there are a lot of households that don’t have cars. They don’t take into account that there’s a lot of existing supply [of parking space] on the streets.”

If you want to mandate off-street parking, Jordan said, “you’re going to have to cut down trees and you’re going to have to pave more surfaces.”

It’s much better, Jordan and others are arguing, to let property owners make site-specific decisions about their parking needs.

But parking reformers face a political challenge. How to eliminate parking mandates without triggering a “war on cars” freakout?

Oregon’s latest win, along with recent reforms in Washington, California, Minneapolis, and Portland, offer one possible answer: Embed the parking reform inside other reforms.

By embedding their parking reforms in efforts to create more and cheaper homes, these states and cities focused attention not on what their residents stand to lose (abundant parking space) but instead on what residents stand to gain (abundant and cheaper homes).

Morris, the Eugene-Springfield tenant advocate, said that’s the way he thinks about the issue.

“Our health, our planet, our future—the benefits are really grand and the negatives are slightly less parking,” he said. “So I’ll take the pros with the con any day.”

— Michael Andersen, Sightline senior researcher, writes about housing and transportation: (503) 333-7824, @andersem on Twitter.

— Get our headlines delivered to your inbox.

— Support this independent community media outlet with a one-time contribution or monthly subscription.

Thanks for reading.

BikePortland has served this community with independent community journalism since 2005. We rely on subscriptions from readers like you to survive. Your financial support is vital in keeping this valuable resource alive and well.

Please subscribe today to strengthen and expand our work.

A little correction: It’s the Land Conservation and Development Commission.

Yep, the LCDC, not to be confused of course with the DLCD, the Department of Land Conservation and Development. Love all those acronyms!

And given the headline, not to be confused with the Land Use Board of Appeals. 🙂

Drat, thanks.

I’m just glad that I will never ever have to hear “housing free market” types drone on about a reform that is largely irrelevant to Portland’s low-income housing crisis.

(Note: there is absolutely no shortage of housing for rich people can buy a bungalow, luxury duplex, or even $600K Orange Splott LLC “small home”.)

Just because you don’t care about having an adequate supply of middle-income housing, that doesn’t mean other people don’t care about it or think it’s an important issue alongside the low-income affordability issue. I happen to think both are important and have completely different solutions. These “middle housing” reforms will help deal with the artificial scarcity of housing for middle-income households by tweaking the regulations that make market-rate housing more expensive than it needs to be. To deal with low-income housing shortages, we need direct subsidies to correct for a failure of the market to provide that product in any real sense.

I believe that converting low end rental housing into upper end owned housing is an inequitable transfer of housing opportunity from those who desperately need it to those who have more options.

Agreed. Which is why it’s really important that we have new construction, to fill the demand for upper-end housing units.

What does all that new upper-end construction replace? In my neighborhood, it is the small houses and less expensive rental properties.

But… what would happen in the absence of any new development? Would those abodes stay permanently affordable, or would their rents/prices just go up and become relatively low-quality (but relatively close-in) middle-income housing?

There’s no rule written anywhere about what middle-income people will accept as housing. For example, shockingly expensive abodes in New York City and San Francisco, that upper-income people reside in (not the ultra rich, but say at the 75th income percentile in those cities), don’t have features that middle-income Americans in single-family housing in most of the country regard as basic amenities. I’m talking about, most obviously, in-unit washer and dryer hookups, but also dishwashers and garbage disposals.

If the California Bay Area has taught us anything, it’s that not replacing low-density single family homes with high-density multi family homes results in cheap single family housing

/s

The prices will go up over time, of course. But more slowly than when a house gets demolished and replaced with a million dollar house. Also, the ceiling of appreciation is much lower for a smaller structure.

I’m not opposed to new development (though I wish builders would hire better architects); I’m opposed to demolishing existing housing. In my neighborhood, at least, it’s usually possible to subdivide a lot and build on half, leaving an existing structure in place on the other half. It’s not as profitable as demolishing and reconstructing, which is why it’s not often done.

One thing I think we can all agree on is that (most) development is driven by profit, and top-tier housing is usually the most profitable.

I’ve always found it interesting that many who are skeptical about “capitalism” in other realms embrace it so uncritically when it comes to building housing they aspire to.

But, that ignores the potential add-on effects of net new market-rate housing units in pushing down demand for *other* existing, less-desired housing units. I know you think that every net new housing unit in Portland is filled by a net additional migrant household from California(/etc.), and I disagree, and we’ve already discussed it extensively so let’s not argue about it now. But I just wanted to note that for anyone else reading this.

The construction without demolition I assume you’re talking about is building ADUs, since that’s all there’s room for on the vast majority of Portland single-family lots. Building ADUs on a lot with an existing single-family home on it while minimizing disturbance to the existing structure is laborious – which makes it expensive. You can call that “unprofitable” but the fact is that even in cases where no profit is being made, ADUs are fairly expensive to build (relative to the per-unit costs to build an apartment complex).

I don’t embrace capitalism uncritically; I would much rather have Soren’s vision of 30-80% of Portland’s housing stock being public/social housing than a world where the only change in the housing policy is more building of market-rate units. But we’re nowhere near that level of social housing and won’t be for years (if such a policy is ever adopted). It’s worth being clear-headed about what impact new market-rate development has for low-income folks in the meantime. There are both positive and negative effects.

It just goes to show our value system changes when it is “us” and “them”. There’s some interesting literature out there on this phenomenon…from a sociobiological perspective.

Right, like the Red House, which was providing low cost (free for Sovereign Citizens!) rent, and they wanted to tear it down and build 10+ market rate units in a high-demand neighborhood. Good thing we nipped that one in the bud, right?

I don’t know how long you’ve been in Portland, but that neighborhood is a great example of what happens when development goes wild. Lots of new housing, little of it affordable to the people it displaced. It’s the model that some want to replicate across the city.

N/NE Portland was, by and large, gentrified-in-place (by which I mean, large rises in rents and home prices, leading to much displacement of the previous residents) well *before* substantial new market-rate development occurred.

I don’t like *either* gentrified version of N/NE Portland – the 2005 one with little new development, or the 2020 one with a more sizeable amount of it.

I’ve lived in and around that area for nearly 20 years…and most of the big builds were on major streets that were commercial operations and not homes. Not that many people have been “displaced”. The homes that were there…I suspect they sold their lots and bigger stuff went up.

Ouch!

The second pic, the 4 plex that looks like Bart Simpsons head, replaced a single family home that sold for less than each of the single condos in the plex. So it did not provide any new, more affordable housing. And (no surprise) there have been huge issues with the owner trying to sell them. They are now rentals. Also, the two condos that do NOT have garages have not been able to be sold OR rented. Idealism aside, people own cars and want somewhere safe to put them or to have a space to store stuff, have a workshop, a home gym, or or other large, flexible space. The current definition we have for “affordable housing” is misleading and does not match up with the actual price middle or lower income folks can afford.

“an adequate supply of middle-income housing”

Thanks for being honest about what you want. Instead of advocating for the actual housing that is in short supply — housing for working class and poor people — you want a greater supply of “nice housing” for households earning 70-120K (middle income in PDX). There is absolutely no shortage of high-end apartments for mostly-white middle income Portlanders — just a shortage of “nice” bungalows, mini-mcmansions, and 0.5+ million dollar duplexes.

“tweaking the regulations ”

The OP and most of P:NW had conniptions about the weak and ineffectual inclusionary housing mandate (because it might dry up supply of “middle class” housing). In my opinion, “all housing matters” types don’t really want to tweak the market in any way that addresses housing justice.

“direct subsidies”

So even greater subsidies of housing speculation by a few? Perhaps instead of doing what we’ve been doing for generations, we could look at what has actually been successful — social housing (and its housing price-leveling power). Housingcare for all.

You’re completely conflating luxury housing with middle-class housing. It makes no sense to talk about “high-end” apartments for “middle income Portlanders.” If it’s high-end, it’s for rich people, not middle income people. There is an actual shortage of “middle” apartments for “middle’ income Portlanders. You seem to be deliberately pretending that’s not true, as a way of avoiding that you simply only care about one of the two main types of housing shortages that exist.

Middle class Portlanders are high-income because median household income has rocketed up in Portland the past few decades. Moreover, based on HUD affordability guidelines the vast majority of “middle income” folk can afford the high-end housing that is in ample supply (thanks to overbuilding and the mad dash to buy a pandemic nest in the suburbs, exurbs or some town like Boise).

“we need direct subsidies to correct for a failure of the market to provide that product in any real sense.” Yes, because all of us wish to live amongst $450k+ housing instead of somewhere I can afford?

Yawn.

Dream on, Soren! Still gotta prevent excessive parking mandates from driving up the prices of apartment buildings in the burbs. 🙂

That’s the point of being rich – so you don’t have to go without. I’m not saying that high end housing doesn’t pervert the market or that lower cost housing isn’t needed, but if you have enough money you should be able to buy what you want. Housing, bikes, sushi…

$600K tiny home? That sounds like some hyperbole. Orange Splott LLC has built standard sized homes made permanently affordable via Proud Ground (affordable land trust) without public subsidy thanks in part to Portland’s initial on-site parking requirement waivers.

Eli’s is a for profit owned housing developer* who sells “pergraniteel” single family homes/condos, many of which are sold at market rate. Eli also has financially benefited from a conflict of interest on the PSC by passing a policy that literally deregulated his business model.

Proud Ground does not provide housing for the low-income folk who are in desperate need but rather provides housing for middle income folk (80-100% MFI) who can afford* to live in one of the many empty high-end apartments that our gloriously efficient market has overbuilt. Housing middle income people in “nice” single family homes is simply not something I care about in the midst of this dehumanizing housing crisis.

*based on HUD 30% income metrics

Talk is cheap. Especially the heresay and hyperbole you seem to peddle. I might agree with the values and principles you seem to champion and your sense of urgency, but with all due respect I don’t think you know who or what your are talking about. Eli has led a life and a career of action advocating for and building affordable housing for all income levels (yes including HUD 30%) as a non-profit affordable housing developer for many years and later with his own business building denser co-housing development for a range of income levels. He has done that by pushing the limits of exclusionary single family zoning to create denser, better designed, and more affordable infill community housing. So when he was invited to apply to join the PSC and help reform exclusionary zoning via Residential Infill Project and address other barriers to more affordable development, thankfully he accepted. Eli has been a tireless advocate of a range of policies and mechanisms to expand affordability for all income levels (including transitional housing for the houseless) and has advocated for specific policies (like the real estate transfer tax) to specifically combat the effect of real estate profiteering on rising housing costs. His actions and accomplishments speak volumes of his commitment and success in advancing housing justice.

All zoning is inherently exclusionary. That’s its entire purpose!

True but that’s beside the point here. Single family zoning is exclusionary to low-wealth, low income people in need of housing which is the subject of this post and thread.

Newly constructed “middle housing” is usually even more exclusionary to those people.

I don’t see how that could possibly be the case in the near term or long term. All newly constructed, market rate housing is less affordable but single family residential is especially so. The affordability provisions in RIP will allow new missing middle housing in the near term to be more affordable in some instances. It remains to be seen if the more efficient land-use of missing middle housing, as well as it’s contribution to aggregate supply, will help keep housing costs down over the longterm. It seems to me there are reasons for skepticism about the magnitude of these affects but compared to the status quo and given other factors (rising transportation costs) there is a strong case to be made missing middle housing can contribute to a more affordable community (determined by more than housing costs) over all. RIP is a partial solution to a multifaceted, systemically exclusionary housing system.

I agree that newly constructed single family housing is likely to be even more expensive, but that’s not the option I support. In most cases, it’s less expensive (and more climatically sound) to leave existing housing in place. That’s what I want, and by incentivizing demolition of functional housing, RIP is a step in the wrong direction.

It is potential for this to happen in particular instances but the evidence that new construction of missing middle housing would somehow be worse than a status quo that allows small affordable homes to be demolished and replaced massive very high-end single family homes, doesn’t hold up. Moreover, your argument totally ignores the fact that RIP could just as well expand opportunities to preserve existing structures by increasing incentives to re-use and repurpose them, creating more small and more affordable units while preserving existing structures. Regardless, these issues were thoroughly vetted by the PSC, staff, the City Council and public debate leading up to RIP’s adoption. Unfortunately a lot of people ignore the evidence because they are making a politically provocative not an evidence-based argument. In some cases that’s because they oppose new housing and new neighbors in their neighborhood. Ironically these voices would appear to even oppose the discretely added, more affordable units allowed within existing structures or within the smaller new structures required by RIP. Since these position are politically unattractive, they retreat to evoking this argument about RIP destroying small affordable homes without a lot evidence. If we really care about preserving the character of our neighborhoods, I think we should focus tools that will preserve Portland’s historically mix-income communities over the long term, mixed income communities being winnowed out by overly rigid single family zoning, among other factors. We should be focused on the people not on quaint old homes.

RIP made replacement of existing low-density plex/shared housing with high-end single family housing more feasible and profitable. Given that this reservoir of naturally affordable housing is already at risk for replacement, RIP’s deregulation may end up increasing “exclusion” of low-income folk in inner Portland neighborhoods. When this is paired with mounting evidence that urban core upzoning are associated increases in land value and that very high demand areas (e.g. inner Portland) experience filtering up, it’s conceivable that RIP could end up being a disaster.

“urban core upzoning is associated with increases”

/editing-fail

I don’t know where you get your evidence in the code or on-the-ground but it strikes me as highly speculative. RIP code amendments don’t actually go into effect until next summer. It is important point because a lot of opponents have been blaming RIP for development approved by the existing code, some of which might even be prohibited under RIP. I strongly suspect the immediate impact of RIP will be highly underwhelming for everyone.

Hi Jim, I have followed RIP closely since its inception. In fact, my criticisms of RIP (that can be seen in repeated public testimony from myself and PTU) is that it was designed to be underwhelming while incentivizing housing types that do not address the low-income housing crisis. The provision for deeply affordable 4-6 plexes is good but should have allowed higher levels of density and been matched with greater incentives. It is also interesting that P:NW leadership pushed back hard against proposed amendments that would have limited market rate density as proposed by tenant and affordable housing organizations (which were designed to increase the relative value of the affordable housing bonus).

Note: As a tenant organizer, I along with other housing justice groups, proposed a deeply affordable housing bonus during the BHD stakeholders process. Despite this clear history documented in the meeting notes, P:NW leadership falsely claimed that this bonus was a result of their advocacy and not the advocacy of tenant and community groups.

I agree that RIP does little to change the exclusionary status quo. This is unfortunate because the status quo is increasingly awful with an increasing number of naturally affordable “plexes” and “shared houses” being sold, gutted, and flipped into high-end single family housing. By deregulating the number of SFHs allowed per lot and making it easier to subdivide lots, RIP has made the practice of converting a duplex, triplex, or “shared home” into a large single family home all the more profitable.

I don’t think the status quo is acceptable either. My current thinking is leave RIP in place and overlay it with demolition protections for sound structures.

It is really hard to take claims of “affordability” seriously in regard to RIP, when what it does is incentivize replacing (often) affordable housing with high-end housing. Offering bonuses for adding cheap housing has largely failed in Portland.

I do not like using the word “exclusionary” to indicate expensive housing, as all housing (including free government housing, if we had any) excludes people. I know you mean it as a pejorative, but it’s just redundant. Maybe “RIP is a partial solution to a multifaceted housing system that tends to focus housing production on the most well off”? At least then we’d know what we’re talking about, and we could discuss who actually benefits from RIP.

This is a little off topic, but over here in Bend, parking requirements for new businesses have been dramatically reduced. The result is that bike lanes have become the go-to parking for these new businesses. A lot of these businesses are being built near the city core, and parking is already tight. Now, it is beyond tight and drivers just use bikes lanes. I don’t see how it will be any different for housing developments in the future. and, with Portland basically throwing in the towel on traffic enforcement (sending those teams to precinct work), you can anticipate having lots of cars in bike lanes, and nobody at the city answering the phone, when you call to complain.

Steve, have you brought your concerns to the Parking Dept or City Council? (Another route may be the City’s Risk Manager/ Legal if the City has traffic safety / parking enforcement code that it is not enforcing then they might want to be aware of the liability if a cyclist were to get injured by a blocked bike lane, etc. )

Wouldn’t enforcement hurt poor people or minorities? Can’t do that.

I assume that you were tongue in cheek, but there are only four, or five minorities over here in Bend, and these restaurants pour $7 pints, so no poor (pun intended) people allowed.

JR can only talk about poor or Black people if he’s mocking them.

It sounds like they’re mocking hand wringers rather than any particular demographic group.

Yes…I have talked to Traffic Enforcement. They made no promises, but, in the past, they have done enforcment sweeps in similar situations. Usually, it becomes an ongoing issue. In one case, after years of my complaining, then enforcment, a popular restaurant bulldozed an adjacent field, laid down gravel, and created additional parking. What will happen in this case, I’m certain, is that scofflaws will get the message, and park in the local neighborhoods, then the neighbors will complain, the City will eventually (usually takes several years) issue stickers for local residents. btw City Council over here is a lost cause. Their business bias is so strong that I have never, in 20 years seen them take significant actions to limit development.

I asked earlier but my question got bumped down. What businesses and which street sections are people parking in the bike lane in Bend? I don’t see it very often.

4th ave at Penn, there were 4 cars in the bike lane the day that I called in. Big outdoor bar opened over the Summer.

Went by yesterday; bike lane full of parked cars.

My theory is that a lack of parking minimums somehow generates more assholes. It sounds like Bend is full of them.

Perhaps giving the person parked a 5 minute warning then torching their car is appropiate.

What streets/areas are people using bike lanes for parking? I only see it very occasionally.

Plastic wands would help. I noticed that at the Oregon Convention Center. People parked their cars on the bike lane regularly until the city put plastic wands in. Then the problem was resolved. I am not a big fan of plastic wands for protection, but they do seem to help with parking.

Multnomah Blvd between the Moda Center and Lloyd Center is a good example. When I was commuting along there 2013-2016, there would be nice and clear bike lanes until MLK or so. When the wands and barricades stopped, cars would start being an obstacle. It helped that (iirc) there were also parking spots between those barricades, giving people an obvious alternative to the bike lanes.

In general I am opposed to any new ‘street furniture’. Here in Bend, it won’t work because of snow plowing requirements in the Winter. Similar issue in Portland, just not on a regular basis.

There’s this crazy thing you can do, you can actually make it physically impossible to park in bike lanes by building them above surface level or putting in hard infrastructure to keep cars out of them.

I’d argue the result you’re frustrated with is not due to mandates being reduced, but parking being undermanaged. (And perhaps a need to flip to curbside parking-protected bike lanes, eliminating the conflict).

That is, in places with excess demand, cities can choose to manage who gets to park in the spots through permits, time limits, pricing, or a combination.

DLCD has published a host of publications on how to manage on-street parking better and works with cities who are interested in doing such (we presented at a webinar with Bend staff). I thought Bend is considering doing some pricing downtown.

Mandating a lot of parking – thereby subsidizing driving and usually making streetscapes less friendly to people walking and biking – often isn’t the best approach to meet our many goals.

So does this shift include any Parking Maximums? Or were the minimums just removed?

No maximums were created.

Is that top photo, with all the garages, in Sullivan’s Gulch? Would Portland code even allow for such a structure these days?

I believe this wide of a curb cut would be illegal. Not sure though.

Without looking things up, I think Michael is right that the curb cut is too wide to be approved, plus the parking between the front lot line and the building would be illegal, as would the high percentage of paving, and the percentage of front facade devoted to garage walls.

This building is on Halsey St. near Hollywood. I frequently walk by, and having cars parked right up against the sidewalk, combined with a huge curb cut next to a high-speed street is definitely not great. The other side of the street is much more comfortable, but then you hit a freeway offramp just west of here, which usually has someone blowing the red light to turn right.

I had to look that up. It’s at 45th & Halsey. I was thinking it was another spot, on NE Irving between 20th and 21st. There are two older courtyard apartment buildings with this treatment for 15 garages, and they have the cut angled down much steeper to get to basement grade. It’s great that all the garages are on one street, and the other apartments have the courtyard entrances off of 20th and 21st. This kind of (old) development is a nice look, I’d like to see more.

https://goo.gl/maps/esSNdtGcj851JLYC7

Correct on the location. I don’t geotag my shots, for privacy purposes. Here is my original snap – https://www.flickr.com/photos/memcclure/46419179485

That apartment management company, Bristol Urban, has all sorts of old Portland-y properties. (Clarification: they own the section that’s further from the camera and in better condition. Not sure who owns the near one.) Generally in walkable/bikeable locations too!

Thank you! I was trying to figure out the tall concrete project behind it, the combo reminded me of some buildings in the Gulch where I lived for 5 years, but in fact it’s a mile away in Hollywood – Homeforward’s Hollywood East Apartments for the elderly, on Broadway near Grocery Outlet, TJ’s, and Whole Foods.

Yes, projects that meet the code but only need a building permit (no land use review) sneak through all the time. There are several in my neighborhood. Fortunately they are more affordable and filled with nice neighbors so it’s not too bad, but man it is ugly.

I’m not up to speed on seismic building code but it looks a little fishy in terms of shear wall dimensions.

It should be fine as long as nobody leaves their garage door open during an earthquake.

Seriously, though, totally fishy. But it was built in 1938, decades before any meaningful seismic requirements.

The caption’s “In many Oregon cities, this is how a fourplex would be legally required to look” isn’t quite true. In NE Portland’s Eliot neighborhood, there are several four-plexes on 50′ wide lots with a single standard garage door, leading to at least 6 spaces (1.5 per unit) inside the building, 1/2 level below grade so the garage door isn’t prominent. Some had a few additional spaces in the back yard behind the building.

While I totally support reducing or eliminating parking requirements, I think a one-size-fits-all approach has its downside. Reaching the multi-modal utopia will take time, and some areas will take longer than others. I believe a more nuanced and pragmatic approach to parking would yield better results in the long run. Off the top of my head – a few considerations:

– A big factor related to on-site parking cost is whether the jurisdiction requires a structure (garage/carport) or simply a spot to park on the property. Prohibiting requirements for garages/carports is a great start.

– If parking isn’t provided on-site, cars won’t disappear, they’ll show up on the street. How may times have we had bike lane projects that became extremely difficult or impossible because of on-street parking demand and related political opposition? Instead of parking cost being bourn by the car owner, it’s publicly subsidized as on-street parking.

– More attention should be paid to minimum parking requirements for destinations like employment and commercial uses. One reason Americans drive is because it’s been made relatively cheap and very convenient. Other than the Central City, parking is free and (overly) plentiful just about anywhere.

– Availability of travel options (walkable neighborhoods, bike infrastructure, transit) need to be available for households to realistically rely on fewer/no cars. The availability of these options varies widely across Portland metro and the state. What makes perfect sense near SE Division may be very different in Tigard or Gresham.

Like many issues, there’s no silver bullet.

Downtown Tigard has just about zero bicycle lanes except for parts of ODOT’s stroad of Pacific Highway. Greenburg Road and Hall Blvd have smeared-away bike paint lanes. The Tigard Street Trail has an awful cargo bike-unfriendly gate by the sidewalk where the trail ends.

To me, there’s very little more one-size-fits all than parking mandates.

The data from King County, the Bay Area, Hillsboro, Albany, Corvallis, and Portland show over and over the demand for car parking varies a lot from project to project, even in similar areas. Hence, I’m in favor of letting the market adjust to those nuances (while managing public on-street parking well — which is admittedly difficult work, but even places like La Grande have permits in high-demand areas).

What we’ve seen across Oregon is local builders usually include some car parking (as that’s what their tenants want) even in places without costly, one-size-fits-all mandates. Proposals in Eugene to develop parking-free housing downtown have had the lenders require builders to include very expensive strucutured parking (i.e. parking garages) to get the loans.

Yes, there’s no silver bullet. And you may not be entirely correct that cars won’t disappear – the academic research (albiet limited) is pretty clear providing off-street parking increases car ownership and use. The magnitude of that is still up for debate.

I agree that one-size-fits-all solutions are usually terrible. A requirement to *provide* parking is just as bad as a requirement *not* to provide parking. And when developers are *not* required to provide parking, they often put the burden of providing it on the community generally, since people still own cars and they park them on the streets, making life worse for everyone else.

I’m interested in thinking in new ways about this issue – away from a model where people park in front of their houses to one where parking is an amenity, like shopping, and you pay for it separately. Wouldn’t it be nice to have more developments like Culdesac in Tempe, AZ (https://www.fastcompany.com/90434128/if-you-want-to-live-in-this-new-arizona-neighborhood-you-cant-own-a-car) where there is NO provision for cars of any type? I want a neighborhood where I don’t have to worry about some driver running me over when I walk the dog. People in car-free communities will still own cars – they’ll just have to figure out where to store them, by renting a stall in a garage nearby, perhaps.

I don’t like the way this problem is framed b/c there’s no good solution as long as we keep talking about “minimums.” Instead we should be talking about about a more holistic framework that takes the total car-ownership challenge into account. Right now parking is considered a *free* amenity that comes with car ownership, and that’s just wrong.

There’s nothing in the rules that’s a requirement not to provide parking.

As you note, there is a problem with mismanaged on-street parking.

That’s mainly because cities decide to provide free/deeply subsidized car storage on the public street. And most areas aren’t managed at all.

Want car storage/parking (200 square feet of storage), privately provided? That’ll usually start at $50 a month in low demand areas, going up from there. Probably at least $100/month in areas Portland provides permits. So $600 to $1200/year.

Want an on-street parking permit from the City? That’s $75 a year ($195 in Northwest, unless you’re low income).

So the City is providing an item worth $600-$1200 item for $75 (To be fair, many cities, such as Salem, are $15/year – and it’s hard to directly compare non-reserved spots in neighborhoods with a dedicated spot not near your home).

The politics around this are difficult. People think they have the right to store a car (but not a storage item, or have a parklet, etc.) on the street for very little cost. (You can skim the TGM guide to managing on-street residential parking here).

Fast forward 20 years, when the robot cars have arrived and are widely deployed… urban parking will simply no longer be an issue.

It’s a problem that will solve itself. Squabbling about it now is just a waste of time.

Unclear on the timeline (the promise of self-driving cars has been overhyped, but in theory we’ll get there).

But yes, reducing costly mandates now makes sense given the future reduction in demand for on-site parking at each site. Forcing the building of spaces that will be unneeded in the future into building site plans for buildings that will last 80-100 years is pretty wasteful.

That’s why managing the huge amount of existing parking better makes more sense than building a bunch more.

Awesome! There are a surprising number of those garage-front multi-plexes around Portland. Most can fit one street tree between every third garage door, if large tree wells are added in the curb zone (which is currently wasted asphalt). Here’s one in NW that shows the amount of space in the right-of-way that is available for trees or other placemaking: https://goo.gl/maps/8nquTs2abdwCdXQf6

That’s a great idea. Dividing that long curb cut into several groups of two or three (so you’d drive at a slight angle right or left from the curb cut into the garage) so you had a row of street trees would totally transform the view towards that facade (plus give tenants views of trees instead street traffic).

I wonder if PBOT would balk at not having much clearance from the edge of the curb cuts to the trees (I think 5′ min. is the standard)?

I mean…that is sort of how some of them look in my neighborhood (Kerns). But yeah, I don’t see Oregon going for parking minimums. Certainly not with any projects using public funds.

Two words:

Frontage fees