(Photo: Jonathan Maus)

This is a guest post by Michael Andersen, BikePortland’s news editor from 2013 to 2016. He’s a writer for 1000 Friends of Oregon’s pro-housing campaign Portland for Everyone.

There are two ways for more Portlanders to live in bikeable neighborhoods.

One way is to add good bike infrastructure to neighborhoods without it. The other way is to let more people live in neighborhoods that have it already. Portland should be doing both.

A proposal to increase the number of small and mid-size homes in Portland’s bikeable areas — allowing “gentle density” like duplexes, corner triplexes and double ADUs in the neighborhoods we banned them from in 1959 — is at the city planning commission this month, and it needs your help.

Duplexes and triplexes = cheaper family-size homes

(Photo: Michael Andersen)

Longtime BikePortland readers may remember watching, a few years ago, as I gradually became more and more obsessed with housing policy. In 2014, we were sounding the alarm on Portland’s deepening housing shortage; the next year, the average Portland monthly rent shot up $100 … with even faster hikes in older buildings.

Thanks to a big wave of new apartment buildings since — made possible in part by the falling demand for parking garage space that has made thousands of low-car homes financially viable — we’ve finally seen rents flatten out, at least on average. But that just means the housing crisis is no longer getting worse. If we’re going to bring Portland’s housing prices back down and prevent future crises, we need to change the game. We need to find ways to get more homes for the same cost.

Duplexes, triplexes and narrow lots do this. Two-story wood buildings are 19 percent cheaper to build per square foot than five-story apartment buildings, which means they’re the best path to creating new family-size housing that doesn’t cost a fortune.

The main reason we don’t have more of these small homes is that it’s mostly illegal to build any more of them. Today, 59 years after the city banned attached housing from most of its residential areas, that last generation of duplexes is still sitting in front of us, doing their jobs as the only homes on the block on sale for less than $260,000 each (for example).

More proximity = more biking

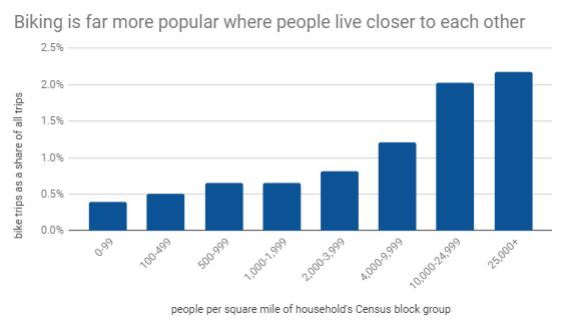

My predecessor Elly Blue wrote in 2007 that proximity is the key to Portland’s bikey future. Data released last month by the 2017 National Household Travel Survey shows that she was right.

The closer people in a neighborhood live to each other, the more likely they are to get around by bike. Moving from an area with 2,500 residents per square mile (like, say, Tualatin) to one with 5,000 residents per square mile (like Parkrose) roughly doubles the chance that you’ll use a bike for a given trip. Moving from Parkrose to a place with 12,000 residents per square mile (like the Belmont, Hawthorne, 28th or inner Alberta districts) doubles it again.

How close you live to other people is a much better predictor of your biking habits than age, race or income. And it’s more effective at increasing your biking habits than a lot of possible street improvements.

This isn’t really a surprise. Even most Dutch people don’t bike for more than three miles or so. The thing about Dutch cities is that they don’t have to. Residential density means the Dutch aren’t far from a lot of the other people they want to visit, and because more people live nearby, there’s enough demand to support lots of businesses within biking distance, too.

Most of Portland’s east side is in that 4,000-10,000 range on the chart above — the third bar from the right. But Buckman, Sunnyside, Kerns and Richmond (Portland neighborhoods with some of the highest bike-commuting rates in North America) are in the 10,000-25,000 range.

Why the difference in density? In part, it’s because those were all neighborhoods we built before we banned small multifamily buildings from most residential areas.

Advertisement

Weigh in now for more duplexes and fewer McMansions

I’ll spare you the fine print of the city’s “residential infill project” proposal unless you want it. (And if you do, I would love to talk to you about the possibility of using a modest FAR bonus and a bonus unit to create an affordability incentive targeted to households at or below 80% MFI.)

The short version is that the plan would re-legalize duplexes, corner triplexes and double granny flats (one attached ADU, one detached ADU) in the middle parts of the city.

This is a deeply controversial concept among people who become upset about the possibility of sometimes needing to park down the block from their house, and those who didn’t seem worried about Portland’s changes until they started to affect buildings instead of just people.

The current proposal would reduce demolitions citywide by setting a new cap on building sizes that would apply no matter how many homes are in a building. (This is why, contrary to the wild-eyed claims of Stop Demolishing Portland activists, it wouldn’t result in mass demolition of existing homes for monster duplexes — new small buildings would rarely be able to sell for enough to pay for both demolition and construction of something new, so current buildings will almost always remain.) This would end most of the 1:1 demolition/McMansion projects that only accelerate middle-class displacement.

The Planning and Sustainability Commission is hearing live testimony for the first time this evening. The online comment deadline is next Tuesday, and the commission’s second and final public hearing will be that night.

There are ways to make the proposal better for density and affordability; if you’re interested, I gave my take on the four most important changes halfway down this post. (The last one: End mandatory parking requirements citywide.) But the bottom line is that in tomorrow’s Portland, for the sake of both housing and transportation, we’re going to need more homes. We should make it legal to fit them in.

The online testimony form is here.

— Michael Andersen: (503) 333-7824, @andersem on Twitter and michael@friends.org

Never miss a story. Sign-up for the daily BP Headlines email.

BikePortland needs your support.

Thanks for reading.

BikePortland has served this community with independent community journalism since 2005. We rely on subscriptions from readers like you to survive. Your financial support is vital in keeping this valuable resource alive and well.

Please subscribe today to strengthen and expand our work.

I urge people to oppose the way in which the city has excluded some neighborhoods from the benefits offered by this proposal. Cully along with a few other places have been artificially removed from the RIP overlay, meaning that the negative parts of the RIP put in place to molify anti development types like an increase to the front setback from 10 to 15 feet will apply to our properties but we won’t get the benefits. It is totally inappropriate for the city to be picking winners and losers with the overlay like this.

All these changes to zoning are wonderful ways to help improve density and bring down housing costs, but we should not minimize the effect of financial policies on the cost of housing. We have had 38 years of steadily declining interest rates which have given the illusion that house prices always appreciate thus encouraging homeowners, flippers and investors to pay more assuming their purchase is a good investment. But since interest rates hit a theoretical bottom a year ago we will inevitably see a long ( perhaps decades) of gradually increasing interest rates. This will affect the cost of mortgages and thus act as downward pressure on home prices. A change in zoning coupled with the end of declining interest rates will usher in a new era of more affordable home prices.

Even though this ignores the actual causes of interest rate increases and the impact those causes may have on the rest of the economy (i.e. INFLATION), this might be plausible (might, because it is tough to ascertain the impact of the connectivity of the internet) in places where housing is a commodity. Most of the entire middle part of the country comes to mind. Housing is cheap because, land, labor, and travel are all cheap and easy. Somewhere like Portland, where there are demand drivers way beyond, “we just need somewhere to live”, will not see this “new era of affordability”. Short of a catastrophic seismic event, prices in Portland are not going to be coming down any time soon and these changes to zoning will be enough to create a rounding error in the actual creation of housing enough to satiate the current demand.

Portland has most certainly turned into a place where you either burn money or time.

In the 1990’s Japan and Tokyo in particular had the highest real estate prices in the world with the land beneath the imperial palace believed to be worth more than Manhatten. Since then they have undergone 30 years of deflation in real estate prices that is not looking like it will stop. Or look at Toronto. A year ago the hottest real estate market in North America on an 17 year steady rise ( no 2009 drop in Canada) but now real estate prices have dropped by 30% in a single year. Demand driven housing prices on work when their is cheap financing and growing incomes backing them up.

Tokyo’s housing is deflating along with everything else. The economy is stagnant, the population is falling, and with a birth rate is well below replacement level, its decline will accelerate.

That could, in principle, happen here, but the dynamics are so different, it’s hard to see us following the same path. And besides, I hear we’re great again.

HK, your “facts” are incorrect.

The Tokyo metro area’s population is increasing due to urban-to-rural in-migration.

http://www.newgeography.com/content/002227-japan%E2%80%99s-2010-census-moving-tokyo

Inflation has been on average positive since 2012 and was only really negative for two years in the past decade (2009-2010). https://tradingeconomics.com/japan/core-inflation-rate

Real GDP per capita has been increasing at about 0.7% per year although at a slower rate than the US’ 1.7%.

https://www.rstreet.org/2016/08/29/japan-versus-the-united-states-in-per-capita-gdp/

Under economic conditions that are broadly similar to larger US metros (growing population, low but positive inflation, low but positive on average GDP growth per capita), Tokyo has shown a remarkably different trajectory on housing prices.

Your initial “reasons” why Tokyo isn’t an example of allowing more housing to be built doesn’t helping reduce housing prices doesn’t fly. What other “reasons” do you have? If you state any “facts”, could you be sure to Google them first? Thanks!

I stand corrected. The population growth of Tokyo is about 0.27%, and their inflation rate, while negative as recently as 2016, is now low but positive. (I did in fact google the population of Japan, which is, as I stated, falling, but I presented it in the context of Tokyo, and was therefore misleading.)

I found this, which is presented only as a tangential item of interest, but is quite sobering. My guess is that Japan will be welcoming foreigners soon.

A recent study by the Tokyo Metropolitan Government, which included a group of academics and city officials, estimated the population of Tokyo in 2100. The group estimates that Tokyo’s population will be just 7.13 million, compared to 13.16 million as of the 2010 census. They also predicted the city will peak at 13.35 million in 2020 before a relentless downslide. Meanwhile, Japan’s population as a whole will decline by over 61% by 2100.

Meanwhile, the Japan Times forecasted that the entire population of the Prefecture of Tokyo, which is the central jurisdiction of the metropolitan region, will be cut in half between 2010 and 2100.

This means that Tokyo’s population is expected to halve in the next 90 years, and by 2100, 3.27 million of the 7.13 million residents in the city will be over the age of 65. The working population of the country, which is largely concentrated in Tokyo, will age, and Tokyo’s place as an international city will be at risk.

I apologize, the tone of my above comment was mean and accusatory. I shouldn’t have done that. Nonetheless, the facts are as they are. Tokyo stands as a strong example of loose development policy and low housing prices in a large, rich metro area. I would argue that the relationship is clearly causal. Housing bubble before loose development, low or slowly declining housing prices for decades after loose development. Yes, economic and population growth became slower at around the same time – but that is also true of the U.S., and we have seen monumental housing prices increases and bubbles since then.

Apology accepted.

Regardless of your fact checking opus, Tokyo is a terrible comparison to Portland, or anywhere in the US for that matter. The banking/finance environment that contributed to the real estate bubble in Japan into the beginnings of a demographically triggered deflationary economy is not similar to the US enough to be relevant, at least not for another 30 years when the boomers are gone. Much like comparisons to the interest rate environment in the 80s is a very I’ll conceived correlation.

There is no evidence whatsoever that this proposal will reduce the cost of housing. The city no longer makes this claim, the city’s economists assert it won’t, and even Michael Anderson can’t believe that, as he recently argued that it would only create 86 new units each year.

So support this proposal because you like density; support it because you like the way new houses fit into our neighborhoods; support it because you are a developer… but do not support it if you are interested in cheaper housing.

https://medium.com/@pdx4all/portlands-residential-infill-project-still-has-major-flaws-housing-advocates-say-6a225ec290e

Hear, hear, HK.

Wait, I thought you thought new housing made prices increase. So why is it a good thing that the effect of this proposal on net housing production is essentially zero?

The problem is not new housing per se, but the loss of less expensive housing. Building a well designed, moderate scale 4-plex in a parking lot, for example, is great. It is the destruction of less-expensive housing to build high-end units, as well as the construction of buildings that don’t fit well into their surroundings that I oppose.

Isn’t demolishing fewer buildings to build essentially the same number of units kind of the whole point of RIP?

No — demolishing more buildings to build more units is the point (or, if you were cynical enough to look at who is on the committee, you might think its goal was to increase business for developers).

If you wanted to slow the rate of demolition, you might add some disincentive for demolishing serviceable structures that could instead be internally converted or otherwise used as rental property, or lower (but not low) cost houses for families.

Every lot in my neighborhood will be able to add a second unit under the RIP. Zero lots here have room to add a detached unit. Most houses here cannot be very readily altered or expanded to add a second unit. Therefore any new unit created here will most likely be done by demolishing a house. And the incentive to demolish a house here in order to replace it with another isn’t great, but the incentive to demolish one to replace it with two units is much greater.

Problem with increasing interest rates is that although they will put downward pressure on home prices, they do so by making mortgages more expensive. That will cause more people shift to renting, putting upward pressure on rents.

Put in economists’ terms, owner-occupied housing and rental housing are substitute goods. Upward cost pressure on one (in the form of higher interest rates) will cause upward pressure on the other.

If housing prices fall as mortgage rates rise, and do so in tandem such that the cost of buying a house remains the same (with the split between the bank and the seller changing in the bank’s favor), there should be no impact on the rental market.

That is so not what happens when interest rates rise. Housing prices are notoriously sticky (i.e., supply is extremely inelastic) in the downward direction, for reasons that should be obvious. So when interest rates rise, it pushes the cost of buying a home on a mortgage a lot more than it pushes prices down. Those of us who were around during the 1980s remember those times well.

Sure, in a vacuum. In a dynamic economy where there is inflation in other parts of the economy, namely wages, and demand drivers beyond shelter, there will not be downward pressure on housing prices. Particularly in the localized close in markets in Portland, maybe houses start selling for 5% over asking price not 10% anymore, but you’re not going to see value erosion.

It sounds to me like you’re saying there is still headroom in the housing market, if the price of a house can remain static even as costs rise. That would suggest that people may be underpricing their houses now.

Yes, I would argue there is still headroom. The delta between Portland prices and everywhere else on the west coast will continue to drive demand even as interest rates rise. Don’t get me wrong, some folks will be pushed down to lower cost homes and invariably others will be pushed out of the market all together, but there isn’t anything close to a healthy amount of inventory on the market at this point that would suggest prices are anywhere close to decreasing in an attempt to lure buyers.

I agree with you. The west coast is becoming a single market, and while prices will likely never equalize dollar-for-dollar, they will reach an equilibrium that we haven’t seen yet. Given that the number of people in this market is effectively infinite, and the amount of land we have available isn’t, and given the limits of our infrastructure, I think it is folly to think we can build our way out of this pickle.

This is why, in one of my rare agreements with Soren, I conclude relying on “the market” to fix the housing crisis will end in tears.

Agreed, the perception for most folks outside Portland on the west coast is that there is a quality of life adjustment and that will likely keep prices here less than the others.

As far as the market dictating the solution, you are probably right, it will end in tears, just a matter of time to see who’s they’ll be.

I agree. As expensive as Portland has become, Seattle is shockingly more expensive these days. And of course the Bay Area is shockingly more expensive than Seattle. Unfortunately Portland still looks like a bargain to a lot of people with money.

Are they?

According to the city’s own study the Residential Infill Project is a complete wash when it comes to providing more housing:

“…our analysis indicates that the proposed changes in entitlements would likely result in a lower rate of development and redevelopment in the study area, yielding less in terms of residential investment but likely a similar number of new units.”

https://www.portlandoregon.gov/bps/article/678769

Andersen’s medium piece (linked above) also has this choice quote:

“According to Johnson, the net impact of the infill project on Portland’s housing count would be 86 extra homes for each of the next 20 years.”

86 extra homes over 20 years.

What a joke.

https://medium.com/@pdx4all/portlands-residential-infill-project-still-has-major-flaws-housing-advocates-say-6a225ec290e

I would suggest that Portland For Everyone, 1000 Friends for Oregon, and many pro-market advocates have put so much time into this failed process that they are willing to settle for anything — even a hollow victory.

Hating on urban McMansions should be something that we can all get behind. The rise in popularity of these structures is the most palpable evidence of poor zoning policy and perverse financial incentives.

And the city/county is going to get additional tax revenue from where else exactly?

Water bills.

Building a new single family house on a single family plot isn’t a loss in density.

Building a single family home on a single plot is different than maxing out square footage by putting up walls at the offset limits to raise the price of a house. The result is underutilized indoor space at the sacrifice of important functionalities of the urban landscape. No trees, no visual space, less light and the trade off is an oversized lazily designed box. It is mindless market driven design that is an externalization of greed and dull thoughts.

Still no change in density.

Exactly, you can be pro-density, anti-density or pro-density but support anti-density policy and still hate on urban McMansions.

No, but it precludes that lot from increasing in density for many decades to come.

And not knocking down an existing structure is more environmentally friendly. Choices, choices.

Except more units closer in, tends to reduce SOV travel and thus emissions, as well as increasing customers for walkable businesses.

A problem, though, is that Portland seems to consider “density” only as “number of units”, not “number of people”. What’s better, a large single unit designed to house 3 generations, or two expensive smaller units designed to house only one or two people each? The RIP says the latter, even though it may have half the number of residents for the lot.

Two units are definitely better — more profit for the developer.

But those lot-filling monstrosities typically don’t house three generations. Realistically, greater density of units correlates with greater density of people.

I agree they typically don’t, but what I don’t like about the RIP is that it makes the ones that do–or would–just as illegal as the ones that don’t. The dark side of Portland’s land use regulations over the years is that restrictions are created with the idea of restricting a particular type of bad development, but with the unintended consequence of restricting some of the most innovative. Some of the people who view that as particularly unfortunate are some of the same planners who have created the regulations.

The RIP also has limits that are far lower than “lot filling monstrosities”. It may have changed, but at least the earlier drafts had a 2,500 sf limit for a 5,000 sf lot. A 2,501 sf house is hardly a monstrosity. On some blocks in Portland, it would be smaller than the average size of its neighbors.

BTW, instead of designing AVs, car manufacturers should be designing cars that can be parked on top of each other if parking is so f* sacred.

The city mailed a Cliffs Notes version of this to us about our R2.5a lot a few weeks back.

A detached ADU would finance itself but it doesn’t pencil out if our legacy (pre-renumbering!) duplex gets reassessed. That’s just how our broken tax system works.

Your existing duplex doesn’t get reassessed. The detached ADU is assessed as a separate new construction unit, so you’ll pay full, current taxes on the ADU. That will be added to the assessed value (i.e. massively discounted) of the current building. SO yes, your taxes will jump, but it won’t be because of a delta on the existing building.

The primary structure will have its assessment reset, unless the rules changed very recently.

Another issue facing Portland, Multnomah County, Metro and the other local governments in Oregon is the inability of property taxes to keep up with rising costs. Residential property tax increases have been capped at unrealistically low levels since measures 5 and 50 were passed in the 1990s. However, when a new house is built, or a major capital project undertaken on an existing house, the tax base is reset to current market value. For example, we live in one of two houses that a developer built in 2014 after demolishing a 1950s ranch on a 10,000 sf lot, the new houses are around 2,000 sf each and have 5,000 sf lots (not McMansions by any stretch of the imagination). The property taxes on the old ranch house were about $1,800 per year, each of the two new houses pays north of $6,000 per year, a six-fold increase. In my neighborhood a lot of really dilapidated housing is being bought up, demolished sub-divided and rebuilt, the new homes are, to my taste at least, more aesthetically pleasing than the old, they are usually two-storey, meet modern building codes etc., and often allow for greater numbers of people – a neighboring corner house was demolished after we moved in and was replaced by three new houses, where one person lived, now four live, $1,500 in taxes became $13,500.

I like the services the city has to offer, but they have to be paid for somehow, short of repealing measures 5 and 50 (did I see a flock of pigs flying by?), the only way to substantially increase the tax base is to encourage the demolition and replacement of old, worn out housing stock. I don’t think anyone will miss the houses being demolished in my Portsmouth neighborhood, and homes with real architectural value usually don’t get targeted for demolition. I think the opposition to infill is basically fear mongering and trying to freeze the city in time (NIMBY, but my aesthetic values are superior to yours type). I think that the 1959 ban was either consciously or subconsciously racist and classist and I think that the sooner we get rid of it the better. Personally, I love the aesthetics of row housing, but not everyone shares that view.

Maybe we just need a residency tax.

Agreed 100%, though I would add (more flying pigs probably) a sales tax would also supplement the needs of the city/county. No, not on groceries. Yes, on prepared foods and just about everything else. Yes, sales taxes are regressive, that is the point, everyone pays in something relative to what they spend. It doesn’t take an actuary to determine that at 9% income tax and $9,500 in property taxes for the privilege of living in Portland, you aren’t seeing a return on your investment.

The residential infill project is a NIMBY delight. Height limits, density limits, and essentially no missing middle expansion of exclusionary zoning. It seems to me to have been specifically designed to discourage creation of affordable rental housing units. Given the exclusion of tenants and tenant advocates** from this process, this is no surprise.

Even the language that Michael uses in his accompanying piece underscores the focus on “ownership”:

Apart from the questionable math that a fourplex condo would pencil in at $250,000*, a “drop in the bucket” ownership model will do little to address our chronic and continuing affordable housing shortage.

I was a tepid supporter of RIP but I can no longer support it.

RIP may very likely benefit high income people who hope to own a small house, row house, or condo but it does nothing for housing insecure tenants. If RIP ends up largely producing expensive owned housing, it may even provide a further boost to the price of land (and rent) resulting in further economic displacement of tenants.

**Affordable housing nonprofits are developers, property managers, and landlords. Affordable housing providers are allies of tenants but they do not speak for tenants and their interests do not always overlap with tenants.

#Fourplex condos are selling for 400K+ in RIP overlap neighborhoods.

And who the heck would sell a unit for $250K, regardless of their costs, if they could sell it for $500K?

Do you own or rent, Soren?

I’m not following your reasoning that it would discourage affordable rentals and benefit those who want to own. I’m currently drawing up plans for an ADU. That ADU will get rented out. I’m not sure what rent would be on it, but it will be a very nice home and I guarantee you it’ll be substantially less than a glitzy apartment. If I can build 2 ADUs, or duplex my house and also build an ADU–why’s that not good? Yes, as the owner I derive some benefit in having someone finance my ADU, but it seems to me to also encourage affordable rentals.

I’m curious: why aren’t you going the Airbnb route with your ADU?

How is it that the increased density is helping anybody? A house in Irvington can build a 400 square foot ADU and rent it out for $1800.

A developer can buy a $500,000 house, tear down the building, divide the land and build a 4 plex where each house sells for $750,000 (7th and Thompson) As these projects make money, there is more pressure on the other properties that could sell for $500,000 and displace more people.

That lot is not part of the RIP. It is zoned R2 multifamily housing. Unfortunately, Portland’s zoning code greatly incentivizes construction of expensive large-unit housing on the small percentage of land that allows apartment buildings. Zoning code in this city is fundamentally anti-renter.

Development in residential zones is also fundamentally anti-renter; most frequently cheap rentals are converted into upmarket owner-occupied properties.

“most frequently”

Laughable. First of all, even small apartment buildings are prohibited in residential zones (R7, R5, and R2.5). Secondly, residential areas are being strip-mined by speculators who are flipping shared rental housing into expensive owner-occupied housing. For example, my neighbors of 12 years were just evicted without cause due to this exact kind of speculative turn over.

In my experience, opposition to rental housing has little to do with any genuine interest in affordable housing and everything to do with a desire to keep neighborhoods exclusive. A recent example of this was the withdrawal of an amendment that would have displaced a parking lot in order to create 45 units of deeply affordable housing due to concerns about…wait for it…neighborhood character.

http://www.koin.com/news/local/multnomah-county/new-zoning-proposal-concerns-ne-portland-residents/1117431622

I reject the notion that residents seek “exclusive” neighborhoods, at least in inner SE. A much more plausible explanation is that people are concerned with parking and large buildings, you know, the things they talk about at meetings and on NextDoor, and amongst one another.

When people in Portland say “neighborhood character”, they almost always means architectural character, not keeping specific people out. Which makes sense… those 45 new units would certainly be occupied by wealthier-than-average tenants — the riff-raff could never afford to live there.

Sorry, my mistake; in this particular case, renters would be of lower-than-average income. Nonetheless, it seems implausible that people would oppose this building for completely different reasons than they oppose apartments for high income tenants.

If you delve deeper, you’ll often find that “neighborhood character” is often used to mean they type of people who live there, or their tenancy. I talked with a Laurelhurst resident at a SEUL meeting, and she explained that she didn’t want any renters on her street, as it was a “family neighborhood”. I pointed out that she had just explained that her children had moved out long ago, so her household wasn’t really “family” in that sense. But she said they all come and visit on holidays, so that still qualifies. She didn’t like renters because the had loud parties and parked their cars on the street. The “Character” seemed to be defined by who lives there. You won’t see folks readily admitting that, though, and some seem to find it convenient to go to the “architectural character” argument. I’m sure some are genuinely concerned about the architecture, but not all.

That woman has a bit of a problem then, if Laurelhurst is like other inner neighborhoods. There are probably already plenty of renters in her midst.

Change the zoning on the main building to commercial in a residential zone so that we can build apartments on the parking lot, then after we get that, since it’s zoned for it we can tear down the old church and build anything we want under the new zoning.

That story isn’t a bunch of nimby neighbors not wanting low incomes. it’s people who invested in a home not wanting everything changed so that a ton of units get crammed on a small lot and a big old church getting demolished for a version of a strip mall.

“since it’s zoned for it we can tear down the old church and build anything we want under the new zoning.”

the affordable housing was to be built on a parking lot. are your seriously suggesting that we should “preserve” parking lots?

the developer’s public plans were to renovate alberta abbey and they also publicly stated that they supported seeking historical landmark designation. moreover, the church lot is already zoned to allow for multifamily housing so it is fmisleadingalse to suggest that a zoning change would necessarily make it more likely to be torn down. why has it not already been torn down?

the neighbors who killed this amendment were specifically upset that the church might support affordable small business space (something that has completely disappeared in the alberta area). their public testimony also makes it very clear that most of their concerns were about a possible impact on parking. their claims to be concerned about preservation are nonsense given that all the parties supporting the amendment were willing to help preserve the alberta abbey.

this developer is one of the few developers in the portland area whose entire focus is on building deeply affordable housing. as a result of this fiasco they have stated, in public, that they are considering leaving the portland area. (their current projects would have built 160 deeply affordable housing units.)

Whatever is allowed, developers will ALWAYS go for the option that gives them the most money. What developer won’t throw in some concrete countertops, some barn doors and a pallet wall to maximize what they can sell it for.

I agree completely. Apart from directly building more social housing, Portland can use regulation and fees to disincentivize high-margin luxury housing and incentivize needed affordable housing. The city has the ability to bring our broken housing market into balance — the only thing that is lacking is political will.

“Portland can use regulation and fees to disincentivize high-margin luxury housing and incentivize needed affordable housing. ”

That’s just a real good way to encourage a developer to develop elsewhere.

There is, hopefully, a sweet spot somewhere in the middle, when requirements for affordable housing are minimal enough that developers see it as worth it, to get higher entitlements (more FAR, more height). There is one local developer (UDG) who is building mixed use buildings now with the Inclusionary Zoning. But it hasn’t seemed to work for very many of them. So perhaps it needs to be dialed back a little. And the incentive will go up slightly on May 24, when the Comp Plan goes into effect, and the FAR on MU zoned lots goes from 3:1 to 4:1, and a fifth floor is available to use that extra FAR. OTOH, in Jan. 2019, the “introductory rate” of 15% of units required to be affordable (at 80% MFI), goes up the “standard” rate of 20% required, so that may dampen uptake again.

And, I should add that the ideal would be that enough housing was allowed to be built in places where builders want to build it, that a massive increase in supply would keep up with and even get ahead of demand, lowering prices. But Portland politics prevented the city from doing enough upzoning during the Comp. Plan to do that, so we’re left fighting for more housing on a site-by-site basis.

I dislike those sorts of incentives because the people who gain the benefit are not the same as those who pay the price, which is usually the immediate neighbors. I don’t object to incentives per se, but want them to be borne by the city as a whole. A cash incentive is one such mechanism.

middle of the road guy’s argument can be summed up as:

subsidies that inflate housing prices are necessary and “just the way things are” (because…erm…capitalism) but disincentives that decrease housing prices are impossible and communism.

Portland’s rents aren’t outrageous because density has increased; they are outrageous because density has not increased sufficiently to meet exploding demand.

Put another way, the ridiculous increases in Portland rents aren’t due to the relatively modest increase in housing supply, but because of the much greater increase in housing demand. Distinguishing correlation from causation here is pretty basic microeconomics.

If we had built enough expensive new apartments to meet demand by high-income renters, that would have reduced price pressure on older buildings that can be rented out for less.

Then we’re in luck! Rents at the top end are holding steady, or even falling, and vacancies are on the rise (and we’re still building). Those lower-end units should start opening up any day now, as people decide they want to spend more on rent by moving to a more expensive building.

One can hope.

we have had enormous “demand” for lower-income rental housing for decades. when exactly is “filtering” going to fix this strange irrational market distortion? it’s also funny how the mantra that “filtering” will address affordability someday (despite the fact that housing prices are a textbook example of inelasticity and subsidy) is taken as gospel but no evidence is provided.

come on, pro-crony-capitalist-free-market folk, show me your filtering data. i dare you!

and, fwiw, i’m enthusiastic about building more housing. in fact, i would happily burn every ADU, rowhouse, duplex, and triplex to the ground if we could replace them with modest 3 story apartment buildings.

The speed at which Sellwood is becoming a place where you can’t buy a house for less than $400k or $500k, according to the above animation, tells its own story. Pushing working class people beyond the Urban Growth Boundary (and Tri-Met’s as well) isn’t the answer. But that’s what these ever increasing rents and housing prices are doing. And many of these fringe areas don’t have good ped/bike facilities, either.

That’s the price of being a desired progressive paradise – there isn’t enough housing. Portland is a victim of it’s own marketing and success.

Let’s say we try to subsidize housing just because – who pays for that and how much? What income levels get aid, which don’t? After a certain point, it no longer makes sense to be a landlord – you’ll sell the property to a developer because it is easier to do so.

I can’t figure out the online testimony link – it seems to just be for the in-person meeting information. I would love to write the city in support of this.

Maybe your browser isnt’ displaying the whole form? Here’s what I’m seeing:

https://dl-postcarbon.tinytake.com/sf/MjU4MDMxNV83NzYyNDUx

At this link:

https://www.portlandmaps.com/bps/testify/#/rip

We need to see more of Michael here.

tough issue. made tougher because it isn’t a problem entirely of Portland’s own making. I’m not yet convinced that the increasing concentration of wealth that is driving housing trends in this town is something that can be effectively addressed locally. local development policies are certainly part of the picture, but I don’t think they constitute the lion’s share.

in a different economic environment, allowing or encouraging incremental increases in density–as proponents suggest the RIP will do–might be a viable solution. I don’t believe it will solve much of anything in this case. barring a major upheaval in the way things are going (locally and globally), I don’t know what a better option is.

“Greater density of units correlates with greater density of people” sounds obvious, but think it’s often not true, at least in the case of 2 units on a lot vs. one, which is a focus of the RIP.

In my own immediate neighborhood, it’s certainly not true. My immediate neighbors are three houses–housing a four-person family, a three-adult family, and a house shared by four roommates–and a triplex, housing two adults and a mostly-vacant illegal airbnb. There are several other two-unit properties, all with one or two adults, and again often-vacant illegal short-term rentals.

So in general, the single-unit properties average more residents (not per unit, but for the whole lot) than the two- and three-unit properties.

And the topper is affordability–the four roommates in the single-family house each probably pay well less than half the rent that the triplex residents pay.

A redevelopment near me razed a $500K house where 4-5 tenants lived, and replaced it with two almost million dollar homes, which, combined house a single person. The rest is, similar to your neighbors, an illegal Airbnb.

Not to pick on the RIP–although I am–there’s also the issue that when the potential number of units allowed on a property is increased, that raises the price a developer is willing to pay for it. So someone wanting to buy a house to live in has more competition from buyers wanting to buy it to redevelop with an additional unit.

Yes, the additional unit is created if the developer buys it and redevelops it, but it also means the RIP just made existing houses cost more for everyone buying them.

Similar thing has happened in my neighborhood with short-term rentals–a house went on the market, then was taken off and an additional unit was bootlegged in illegally, then it went back on the market at a higher price with “ideal for an airbnb” added to the description.

the irony is that some of the nimbys who support exclusionary zoning also bristle at any restrictions on their ability to sell their rental property. imo, we need mandatory registration of all shared rental housing, eligibility of all shared rental tenants for RELO, and a ban on all sales and redevelopment of shared rental housing that would result in lower density.

I’ve read the article and the comments and I’m still unclear on how the RIP will effect my neighborhood. I’m a homeowner on a corner lot and I’m thinking that if fourplexes go up on every other corner, we’ll probably lose the “family neighborhood” vibe. Maybe my kids will be in college by then and not want to play catch out in the street… The question that keeps popping up in my head is, where is the discussion on rent control? Wouldn’t that have a positive effect on rent, housing prices and development? Maybe not for landlords…but for working class folks?

Rent control is less profitable to the developers on the RIP committee.