If all goes according to plan Multnomah County will begin work on a new “earthquake ready” Burnside Bridge in 2024. On Monday, the community task force charged with decided what that bridge will look like reached a big milestone by choosing the “long span bridge” alternative.

Here’s more from the County:

The long span bridge alternative (PDF) would replace the existing bridge in the same location and alignment. The long span alternative has the fewest support columns of four alternatives that were studied. Fewer columns avoids costly construction in geotechnical hazard zones near the Willamette River and restricted spaces between lanes of Interstate 5 and the Union Pacific Railroad tracks on the east side.

Task force members cited these reasons for choosing the long span alternative:

— Best for seismic resiliency – locating fewer columns in liquefiable soils gives it the least risk from soil movement during an earthquake

— It is the lowest cost of four build alternatives ($825 million compared to as high as $950 million for the most expensive option)

— The reduced number of columns also benefits Waterfront Park users, crime prevention, and preservation of the Burnside Skatepark

— Additional deck width over the river provides a safer facility for bicyclists, pedestrians and other users

— Reduced impacts to natural resources due to fewer columns in the water.

The long span option was chosen over other alternatives that included a a retrofit of the existing bridge or a new extension ramp onto NE Couch that would have replaced the existing curve. The final design isn’t decided yet (that process begins this fall).

Advertisement

“I’m very surprised to not see bus-only lanes in both directions while we give four lanes to cars.”

— Catie Gould, PBOT BAC member in a September 2019 meeting

Also this week, the task force decided to not build a temporary bridge during the construction phase. That bridge would have cost $90 million and task force members felt that the minimal travel time savings the temporary bridge would provide did not justify its cost, additional in-water impacts, and the extra two years of construction it would require.

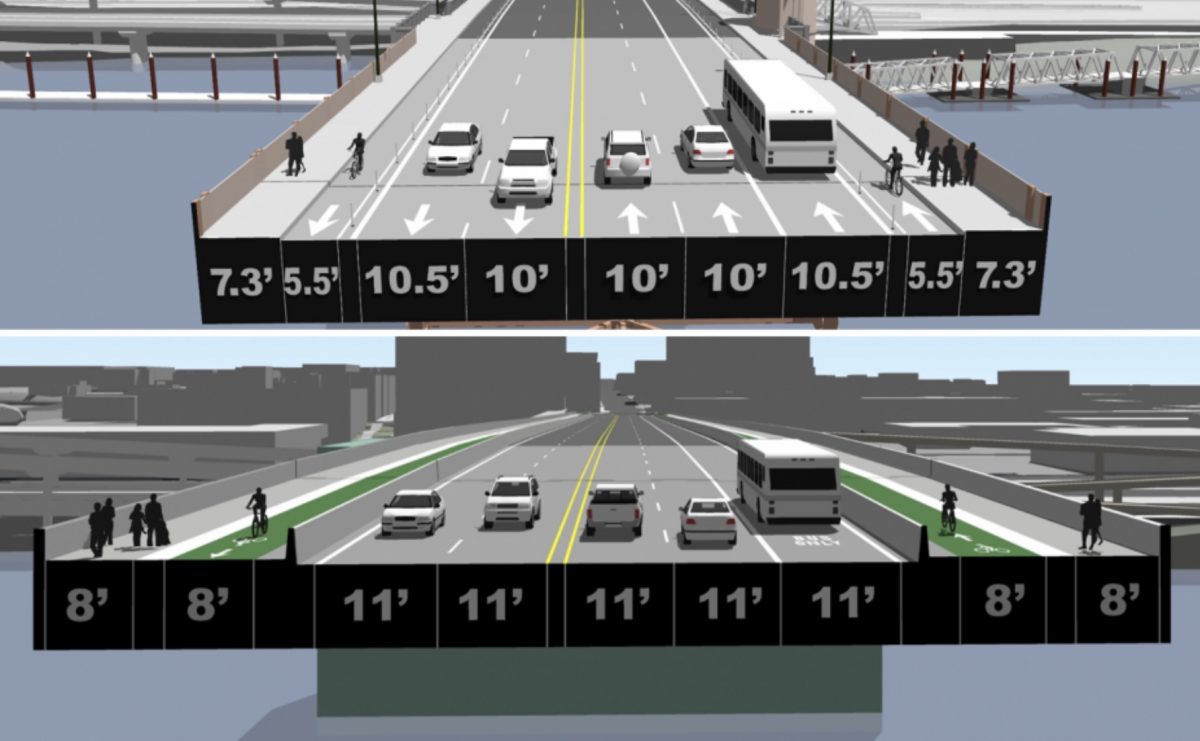

According to potential cross-sections provided the County, the new bridge will come with 8-foot wide protected bike lanes, that’s 2.5 feet wider than the current bikeway. The space for driving would also increase from five lanes and 51 feet today to five lanes and 55 feet on the new bridge.

When County staff presented their plans to the PBOT Bicycle Advisory Committee in September 2019, some committee members were skeptical about the need for so much driving space. Catie Gould said, “Why would we expand the auto lanes? I’m very surprised to not see bus-only lanes in both directions while we give four lanes to cars.” And David Stein said, “This will be the bridge we’re stuck with for the next 96 yrs. 8 feet in each direction [for bike riders] is not going to be enough… I don’t understand given the Climate Action Plan that’s in place why we’re going to dedicate 75% of our space to private automobiles.”

And committee member (and Portland mayoral candidate) Sarah Iannarone pushed County staff to consider an alternative that doesn’t assume dominance by car and truck users. “I want people to see a car-light alternative to show the savings we would get by not having to have car lanes… I think there are a lot of ways to do this project if we don’t privilege the automobile.”

The next opportunity for public input will be an online open house and survey to be released in August. Construction is expected to begin in 2024 and last about four-and-a-half years.

— Jonathan Maus: (503) 706-8804, @jonathan_maus on Twitter and jonathan@bikeportland.org

— Get our headlines delivered to your inbox.

— Support this independent community media outlet with a one-time contribution or monthly subscription.

Thanks for reading.

BikePortland has served this community with independent community journalism since 2005. We rely on subscriptions from readers like you to survive. Your financial support is vital in keeping this valuable resource alive and well.

Please subscribe today to strengthen and expand our work.

Are they going to build the “jersey barriers” between cars and bikes in a way that they can be moved if we want to redistribute space or will they be in a “permanent” configuration?

I’d be willing to give up one of the protected bike lanes (making the other bi-directional) to ensure a dedicated transit lane in each direction. Give the extra 4′ from taking out the barrier for the second bike lane to the single bike lane to make it 12′ wide, and give the 8′ from the 2nd bike lane + 4′ from otherwise making existing lanes wider to make a new transit lane for the other side.

Ideally they’d just take out one of the car lanes instead but I doubt that will happen.

please no! bi-directional bike lanes are not too bad on the bridge, but getting to them is far less than ideal and adds a lot potential risk and inconvenience to people biking. This bridge should definitely be built with safe, convenient and well connected bike and ped infrastructure AND ample space for transit. For this level of reconstruction, there is not reason to not include space for transit. IF it cost prohibitive to widen for a separate transit lane, perhaps one of the car lanes could be a pro-time lane, meaning bus-only during the morning commute.

Often times when there is a one way for a very long time and it has difficult connections it becomes a de facto two-way regardless. A lot of the one-way PBLs in NY are de facto two-way. Making safe and practical connections can counter this behavior.

We’ve got that here as well. Since the Broadway Bridge approaches are a little awkward and feed into MUP sidewalks they are sometimes used as de facto 2 way bike paths in a minimal width. Some people complain if you do that but they don’t lose much time and no actual blood. The presence of pedestrians makes aggressive riding questionable here, and the truss beams (a fairly serious objective hazard for people riding fast and close) afford space for considerate people to yield to others.

The devilish details around bridge design are in the approaches. The actual crossing is a long straightaway and people will sort themselves out and become channelized. Can we learn from the Tillakum bridge? Its value as a human powered river crossing is reduced by the complexity of the approaches.

The Hawthorne Bridge side path is limited in width and has an unprotected drop to a traffic lane. However, it has multiple approaches to both MUP and surface streets at each end, minimum signal delays, and a protected route that avoids the railroad grade crossing. It’s the best bike bridge in Portland for that reason.

I agree with maxD. Bi-directional bike lanes here would be completely infeasible due to access problems.

I was thinking instead, to placate everyone, it might be possible to do a bi-directional transit lane that flows westbound in the morning and eastbound in the evening. Just put it between the two directions of car lanes.

That creates problems for getting the buses to and from the middle lanes. The bus stops on either end of the bridge are on the right most lanes. They would need to invest in a traffic signal phase on both sides to stop traffic so that bus could cross the traffic lanes.

I think a better system would be to have bus lanes in both directions on the outside, then have three general traffic lanes with the middle being reversible for rush hour.

The simplest and easiest would be to just have three car lanes, and pick one direction that would have two lanes. It seems like eastbound would be best. Downtown is always going to be the most congested, so you want it to be easier to going out of downtown than going in.

That’s a good point. Perhaps a bi-directional car lane would be a better idea: two lanes westbound in the morning and two eastbound in the evening, with one in the other direction. Other cities have implemented such systems successfully; look at this one from the Salt Lake City metro area as an example. This would allow for bus lanes and protected bike lanes in each direction. Sure, I’d love if there were only one car lane in each direction at all times, but I’m a realist.

Good to see the article indicates no or minimal safety problems.

NYC has been using similar overhead signalling for years in tunnels and elsewhere. Embracing this simple and old technology could be very effective by allowing us to use limited space that can adapt in real time to what’s actually happening on the ground – not what’s been projected to occur. Bi-directional car lanes make a lot of sense in certain situations – more than we might think.

It might lead to a shift away from one-way couplets back to two-way flexible arterials – a good thing in many transportation circles.

Makes a ton of sense for transit.

I’m in the minority that I’m an active transportation user who actually prefers one-way couplets because I find them significantly less stressful to cross. But yes, I think reversible lanes should be much more widely adopted; it’s a much more efficient use of space than lanes in each direction that are only necessary during commutes.

The Dutch would put in wide bidirectional bike lanes on both sides of the bridge, for all users 8 to 80, including people who are taught at an early age to ride against traffic.

There’s no need for 2 car lanes in each direction over the river. The capacity limits are at signalized intersections, which are located off of the bridge.

Reduce the width of the central roadway to 2 car lanes + 2 bus lanes.

This would allow the new bridge to be built in about the same width at the current bridge: 8+8+11+11 x 2 = 76 feet, approximately the same as the current width.

Exactly! Anyone who’s taken PSU’s Portland Traffic and Transportation class knows that bridges have double the per-lane capacity than most roads, due to the lack of intersections. The bottlenecks are at the ends. When a bridge backs up, it’s because of people waiting to get through the jams at the ends, not because of constraints in the middle of the bridge. Not having protected bike lanes and dedicated bus lanes in both directions would be insane.

There are 43 car lanes on bridges over the Willamette in central Portland (from the Ross Island to the Fremont Bridges). I counted. Cars can lose one lane and it won’t make that much difference.

The proposed width seems right to me. But I agree there shouldn’t be two westbound car lanes. Right now, all westbound bridge traffic comes in on a single lane, where Couch jogs over to Burnside west of MLK. With just one car lane coming in, there’s no reason for more than one car lane on the bridge. The outer westbound lane should be a dedicated transit lane.

This is a bridge between downtown and two eastside corridors. Do dedicated lanes for (self-propelled) buses in both directions even seem like enough?

800 million … remember when people were complaining about the costs of the Sellwood and Tillikum bridges?

Lift span and construction over very developed areas.

Please note that the Community Task Force’s (CTF) votes from Monday are recommendations, not the final decision.

Multnomah County will go out to the public in August to get the community’s thoughts on the bridge option and whether there should be a temporary bridge during construction. The decision about which bridge alternative and whether to include a temporary bridge in the Draft Environmental Impact Statement (DEIS – expected in January) will fall to the Policy Group in October. Ideally the Policy Group will use the CTF recommendation and community input to make their own decision.

The slightly wider car lanes indicates an expectation of slightly higher car average speeds – is this the policy that Portland or Multnomah County really wants to follow given Vision Zero? I’d suggest going to a maximum of 10 feet per car lane and 12 feet for the bus lanes, and using any leftover excess to expand the protected bike lanes.

I wrote to the project team via the web form: https://multco.us/earthquake-ready-burnside-bridge/webform/contact-us and asked that the county re-consider the current lane arrangement. I believe that there should be a bus lane in both directions. Rather than widening the bridge even further, the general motor vehicle lanes should be reduced to 1 in each direction for the central span. The road can widen again at the landings, before the traffic lights: this will give enough room for cars to queue and get through the lights in the signal cycle. The narrower roadway would reduce speeding and crashes, which would otherwise be expected to increase with the wider lanes in the new design.

Yes. Let’s give transit greater priority on a bridge that is the closest alternative to the Steel Bridge, one of the most seismically vulnerable choke points in our regional transit system.

It’s hard to figure out how much each option costs, by looking at the information provided. Maybe it’s buried somewhere, but that’s the frustrating approach to transportation design selection.

Hypothetically, for example, could retrofit mean we also could afford $100 million for walking and biking improvements elsewhere in the city?

It’s the sort of decisionmaking of “define the problem” to force the outcome, or in this case, “the decision is about what bridge design we’re going to build” rather than “the decision is how best to allocate the next $800,000,000 we get.

A significant amount of that is driven by the intentionally and unintentionally obscure labyrinth of transportation funding pots and limitations, so we aren’t allowed to pretend all the funds are fungible. That labyrinth needs to be fixed.

But we also need to frame up decisions about transportation project funding as having opportunity costs. Spending several hundred million dollars (or a few thousand million) somewhere means we’re not spending it elsewhere.

(Glad the $90,000,000 temporary bridge was rejected).

Though, given that a lot of our money comes from the feds, elsewhere might mean Miami.

Soon enough, money spent in Miami is going to become the new definition of “sunk cost”.

#sunnydayflooding

And I’m sure east PDX residents will somehow end up paying disproportionately more for the this bridge than everyone else.

Seconded, Catie Gould, David Stein, and Sarah Iannarone! At minimum one less car lane (or perhaps a reversible, as others have suggested) to help move toward Climate Action Plan goals, and perhaps an often overlooked factor: generally a more pleasant bridge to be on and experience the river and city center! Tillikum Crossing certainly has this aspect, though not as easy to cross by bike as Hawthorne, Burnside, or even Broadway Bridges due to incline.

Gould: “Why would we expand the auto lanes? I’m very surprised to not see bus-only lanes in both directions while we give four lanes to cars.”

Stein:“This will be the bridge we’re stuck with for the next 96 yrs. 8 feet in each direction [for bike riders] is not going to be enough… I don’t understand given the Climate Action Plan that’s in place why we’re going to dedicate 75% of our space to private automobiles.”

Iannarone: “pushed County staff to consider an alternative that doesn’t assume dominance by car and truck users. ‘I want people to see a car-light alternative to show the savings we would get by not having to have car lanes… I think there are a lot of ways to do this project if we don’t privilege the automobile.’ “

Where are the trees? This is a really long way to walk without any shade.

Shade is absolutely important since our climate is now good for tomatoes with olives and citrus in the wings. I doubt if there’s space or a budget for actual trees but there could easily be standards for a renewable bamboo screen or some other locally produced craft. It’s a simple design problem, not everything needs to be metal or concrete.

Why not build it taller to avoid the need for a lift span? If we can do it on the Tilikum, we should be able to do it on the Burnside.

One word: money

Yeah, but the lift span machinery costs a ton of money and adds a ton of complexity. The Tilikum cost less than a fifth of the projected cost of this bridge. The Burnside will have to be designed to handle much more traffic and have a much larger footprint. So of the course the overall cost will be much higher. But I would like to see a cost breakdown of designing a tall bridge without a lift span or a low bridge with a lift span.

I think we should be thinking about the dollar value of the time lost by people waiting for the bridge to go up and down over the next 80 years and factoring that cost into whether it’s really more expensive to build a tall bridge.

Length. The current Burnside Bridge length is 1,382′, the Tilikum Crossing is 1,720′ and is already a much, much steeper climb. To add a point or two of grade is going to make it less accessible to everyone, and add additional fuel usage (and noxious output) on the uphill side, and extra asbestos dust and other brake lining vapors on the downhill side.

A billion dollars. A billion dollars. A billion dollars. It’s worth saying this over and over. Wow. Think of all the things Portland could do with a thousand million dollars. Solve the homeless problem for one. Double the teachers…. It’s mind boggling this bridge replacement is even a consideration. The new bridge has very little over the old bridge. The seismic issue is shaky logic. How many homeless people die on the street every year? It’s entirely predictable. When will this earthquake occur? Will the bridge entirely fall into the river? Will it be at a time of day while many people are using it? Many more lives would be saved by taking the seismic money and spending it to prevent real world deaths that are happening all the time. Risk of homeless death = 100%. Risk of dying due to a bridge collapsing in a five-hundred year or 10,000 year earthquake at the exact moment you cross its weakest part = .00000000000000000000000000000000000000000001, maybe percent.

I don’t think the issue is “dying on the bridge”, but of having more ways to get across the river after an earthquake (and the entire bridge need not fall into the river to be rendered useless; damage or even collapse of the approaches may be sufficient). When a quake might occur, and exactly how big it will be is unknowable, but it’s pretty certain one is coming.

I agree!

I imagine that building a new bridge designed to withstand a CSZ earthquake will be far more expensive than building a new bridge NOT designed to withstand a CSZ earthquake?

If so, why are we building the CSZ-proof bridge?

Suppose we simply let the existing bridge fall down in the CSZ. And have stockpiled some military pontoon sectional bridges, that kind that the Army can throw over the Rhine in a day and send an armoured division of M1 tanks over. After the CSZ, use those pontoon bridges as temporary crossings, while we save lots of money building a new bridge that doesn’t need to withstand a CSZ because the next one won’t be for a hundred years or more.

If the savings is half a billion, seems like money that could build transitional housing for every homeless person in Portland, construct every bike facility ever dreamed of, etc. If the savings is only a couple hundred million, then ok, build the CSZ-proof bridge.

That sounds pretty simple!

Here’s a cool video of how one of those bridges in action, crossing a significantly smaller river than the Willamette: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jpmuTWBxNjs Notice the boats constantly pushing the bridge even once assembled.

You need to acquire the equipment, of course, train people to use it, practice deploying it, maintain it, and find a place to store it where it can get to the waterfront over roads that might not be completely clear. You’ll need fuel available for the boats, especially if you want to keep the bridge in operation for several days, and you’ll need sufficient personnel available to keep it all operational, which is no guarantee after a major earthquake. It also assumes that there is no debris in the river that might get snagged on the temporary bridge, and no need to accommodate river traffic that might be taking relief supplies upriver because the roads are in bad shape.

In the video, the vehicles have a clear pathway to and from the temporary bridge. In our case, You also need to figure out how to deal with the seawall that runs along the downtown side, and how to get an ambulance or truck full of supplies has just crossed a temporary bridge up to, say Water Ave past the rip-rap that lines the bank and the debris of a collapsed I-5 and any relevant buildings.

It’s all possible of course, but a replacement bridge sounds a lot more reliable, and when everything is chaos and panic and is my family ok, reliable and ready to use sounds pretty nice.

Why does the lane diagram remind me of a bridge from the 1950s??