(Graphic: Multnomah County)

“I’d like to see a bridge for our future… but it will take visionary leadership from county, and I haven’t seen that yet.”

— Mark Ginsberg, advisory committee member representing The Street Trust

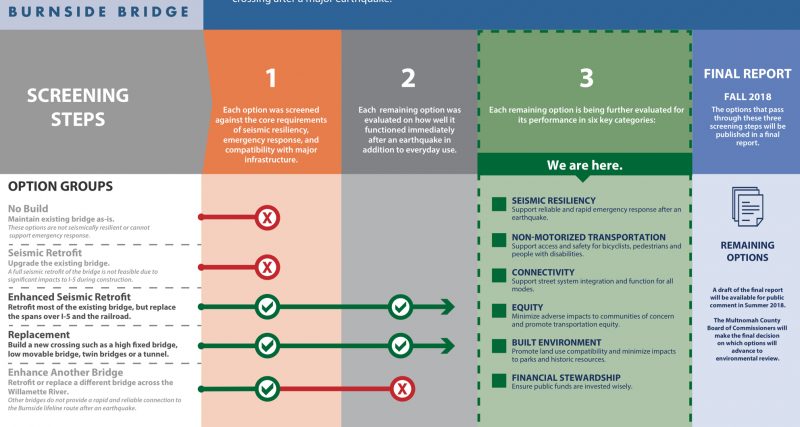

Multnomah County has reached a milestone in their project to make the Burnside Bridge “earthquake ready”. They’ve whittled down a list of 100 options to just two: an “enhanced seismic retrofit” or a full replacement.

The Burnside is a designated “lifeline response route” which means it has special priority when it comes to disaster and long-range resiliency planning. Owned and operated by Multnomah County, the bridge is nearly 100 years old and it shows many signs of age. A separate maintenance project is going on now.

We’ve been watching the Earthquake Ready Burnside Bridge project from afar until this point. With the options narrowed down, the County will now delve more deeply into each one of them in order to determine the future of the bridge.

Here’s where the process stands today…

According to an announcement yesterday, at this point the plan is to either strengthen the existing bridge to withstand a major earthquake and replace the section that goes over I-5 and the railroad, or replace the entire bridge with a fixed bridge, a movable bridge, twin bridges, or a tunnel.

These two remaining options will now be further evaluated based on the following six categories:

Seismic Resiliency

Does the option support reliable and rapid emergency response after an earthquake?Non-Motorized Transportation

Does the option support access and safety for bicyclists, pedestrians, and people with disabilities?Connectivity

Does the option support street system integration and function for all modes?Advertisement

Equity

Does the option minimize adverse impacts to historically marginalized communities and promote transportation equity?Built Environment

Does the option minimize adverse impacts to existing land use as well as parks and historic resources?Financial Stewardship

Does the option ensure public funds are invested wisely?

(Photo: J. Maus/BikePortland)

As you can see, things are starting to get interesting.

This coming spring the County and their volunteer advisory committee will make the final decisions about these two remaining options and by this summer a report will be up for adoption by the Multnomah County Commission.

Bike advocate and lawyer Mark Ginsberg sits on the committee as a representative for The Street Trust. He told us via email this morning that he’s not impressed with the process so far. “I am disappointed in the lack of diversity on the committee,” he wrote. “When setting up the stakeholders only OPAL [an environmental justice nonprofit] was asked to join, when they said it was outside of what they do, no other group bringing minority voices to the table were sought.”

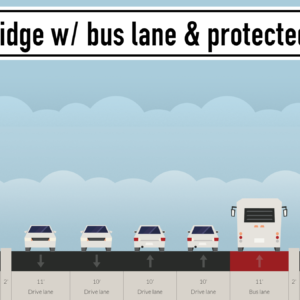

And Ginsberg says he’s concerned the project will be a “lost opportunity for three generations.” “It seems like what we are being presented with is not looking a forward thinking multi-modal plan… We have the chance to make this a world class accessible facility for all of out street users, for wheelchairs, bikes, pedestrians, mass transit and private automobiles, while meeting the needs of water access below, but it seems like we’re just doing more of the same. I’d like to see a bridge for our future, a resilient, safe usable bridge, and it is possible, but it will take visionary leadership from county, and I haven’t seen that yet.”

County spokesman Mike Pullen says whatever comes out of this process won’t be built for another 12 years because it would still have to get planned, designed, funded, and built; but as savvy activists know, decisions made in these early stages will influence the outcome.

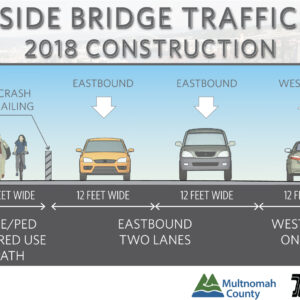

And don’t despair if you want better biking on the Burnside in the shorter-term. Pullen says there are other projects in the pipeline that could result in changes to the existing bike lanes.

The County is on the radar of the City of Portland’s Central City in Motion (CCIM) project. The Burnside Bridge is listed as an “essential link” in the CCIM’s early planning documents, a designation that could result in an upgrade to its bikeway sooner rather than later. And if that project doesn’t net improvements for the bridge, Pullen says the County is actively seeking funding for a list Capital Improvement Projects — one of which would add a buffer zone and delineator posts to the bike lanes. If the County finds funding for that project it would happen after the current maintenance work is completed in late 2019.

— Jonathan Maus: (503) 706-8804, @jonathan_maus on Twitter and jonathan@bikeportland.org

Never miss a story. Sign-up for the daily BP Headlines email.

BikePortland needs your support.

Thanks for reading.

BikePortland has served this community with independent community journalism since 2005. We rely on subscriptions from readers like you to survive. Your financial support is vital in keeping this valuable resource alive and well.

Please subscribe today to strengthen and expand our work.

The lack of a big picture plan drives me crazy. This city should have a solid idea of where we are going in the future so that everyone can be on the same page. If we know that a bridge or a roadway is being replaced down the line we can focus on the replacement instead of what is there now. We need to have routes planned out for streetcars, we need to have a plan in place for bike transportation, etc. Knowing how things get done around here, they’ll plan a replacement and then 2 months later announce the upgrades needed for a streetcar line…..Just like with 7th, they announce a new bridge but still have no idea about the infrastructure needed to utilize the bridge.

Why does this city not have a planned network of bike infrastructure? If they built world class bike lanes on the bridge, then what? You get dumped onto MLK or Grand? with nothing? You work your way over to Sandy? And then what? Why is there not a comprehensive plan for growth over the next 10 years?

Because process and “muddling through” have become the defining characteristics of planning today. In the age of scarce political leadership and funding for progressive and visionary transportation projects, agency leaders have little incentive to put their career on the line to advocate for long-term, costly and politically contentious transportation fixes.

Small scale, piece meal programs are easier to attain public buy-in and agency leaders can boast completing multiple short-term projects in their career timeframe. Planners depend more on public input than expertise when making decisions on transportation projects. The political reality has steered planners to the path of least resistance, and that path rarely delivers us any foresighted solution that will generate the most public benefit through generations.

Just FYI there are indeed opportunities to be involved with planning at a city and regional level. The City of Portland just adopted a 2035 Comprehensive Plan and is finalizing the last stage of a Transportation System Plan Update and Metro is working on a Regional Transportation Plan. If you’re interested in making your priorities known, it’s valuable to sign up for updates, submit comments at multiple stages in the process, etc. I encourage everyone to get involved in the process, as opposed to feeling frustrated/alienated/etc.

https://www.oregonmetro.gov/public-projects/2018-regional-transportation-plan

https://www.portlandoregon.gov/bps/70936

https://www.portlandoregon.gov/transportation/63710

Does this fit the bill? https://www.portlandoregon.gov/transportation/44597

The City does have a planned network of bike infrastructure, and is currently in the process of identifying the priority low stress bike network as part of the Central City in Motion project. I ride the Burnside Bridge every day via the Ankeny Street greenway on the east side and NW 2nd buffered bikelanes on the west side. The transition from Burnside WB to NW 2nd and from NW 3rd to Burnside EB could be better, but I am able to get to work and home just fine.

Portland’s problem is that we over-plan and under-deliver.

Yes, you covered it well before when highlighting the 2035 bike mode share goal was recently revised from 25% to 15% because of what the City can afford to implement and how TSP and Comp Plan implementation impact all those who are interested but concerned. But it’s also definitely the case that transportation funding is out of sync with reality. PBOT is feeling flush for once because of HB 2017, Fix Our Streets, and now likely Build Portland, but they will eventually expire. Ideally we need a more consistent, ongoing funding source, independent of state and federal politics. A 2020 regional measure holds some promise, but can’t get too excited about that just yet.

What would Utrecht do?

Probably something unpronounceable.

that bridge is too big… if they keep it they need to seriously constrain the motor lanes (the narrow lanes on the Hawthorne work well) and put in a (real) separated wide bike lane along with widening the sidewalks… that’s a lot of infrastructure for an old bridge to handle…

whatever is done we need to get cars to be able to go no more than 25 mph over that bridge… chicane the heck out of it… narrow the lanes… put in speed bumps…

right now it’s like a

freewayraceway on that bridge with everybody using the wide open space to gain a car length over the other people racing for pole position to commute through the city…If there were good mode separation, it wouldn’t matter how fast people drive.

Except when one party decides to make a turn…?

I would expect good mode separation to prevent that.

Not sure I’m following. Are you imagining these different modes to be on different vertical planes, not intersecting?

Sure, or a jersey barrier.

What’s the embodied energy of a jersey barrier?

Miami (in spite of the ped/bike overpass disaster yesterday) is rapidly building a regional trail system that uses the East Coast Greenway as its spine, with plans for an east-west Route to Tampa Bay moving forward. Other East Coast cities, such as Philadelphia, are taking the same approach. We should be following that idea, using the Springwater Trail and it’s extended alignment west to the Banks/Vernonia Trail and onward to the Coast as the backbone. Washington State is likely to designate a National Bike Route corridor between Seattle and Portland this summer, which would likely make the I-205 Trail as the likely extension into Oregon for points south. We should be building a regional system with that idea in mind, with Metro’s Intertwine project as the basis. We can’t wait any longer. We’ve got to start moving forward, and we can’t waste time dithering.

Mark raises some good points, especially around who hasn’t been at the CAC table, but focusing on the design at this stage is rather premature, as the process has largely been a technical/engineering focused process. There will be other milestones to ensure we get a much better design than the current one and guarantee comfortable, accessible facilities for people of all ages and abilities.

What concerns me more is the overall lack of planning around how people will get around in the aftermath of an earthquake, especially with related failures around fuel, electricity, etc. The city and region as a whole need to take a deeper dive into aligning resiliency with transportation investments beyond just a single (though very critical) structure, and how we can forecast/utilize the certainy of natural disasters to prioritize a built environment where walking, biking, and transit are safe, accessible, efficient, and convenient for all.

One thought that has come to mind, since this bridge must cross the current I-5 corridor: might it be less costly if I-5 weren’t there? Maybe this could be the impetus to finally remove the Eastbank Freeway and the non-earthquake-safe Marquam Bridge.

Sheesh, 12 years from now when the bridge is slated to be built, we will probably not have fossil fuel powered vehicles for the masses anymore, so fighting over personal motor vehicle lanes will be like fighting over who can have the biggest permit to make buggy whips in 1905.

I can’t tell if you are being serious or trying to make a joke.

Nearly all the major legacy oil fields will be depleted by then at current decline rates ( Gahwar, Cantarel, North Sea etc.) and the shale ” miracle” will have stalled out because no one will be lending the shale industry money to lose selling $60 oil that costs $120 to get out of the ground. New Oil discoveries have dropped to less than 5% of what is consumed in any given year. Shale is the oil industries retirement party. Tune up that bike and get ready for a new world.

In 12 years, there will be plenty of oil. However, I hope we’re burning a lot less of it by then.

Plenty?

For whom?

For anyone who wants to buy it. We are not on the verge of running out of oil. If we stop using it, it will not be driven by scarcity.

Indeed. And myself and several of my coworkers drive all-electric vehicles. So even if oil disappeared tomorrow, we’d still be driving.

Well, actually I would be riding my bike and my wife would be driving, but I digress…

I agree, MORG. I don’t have any confidence that we won’t still have millions of personal vehicles, many of them still fossil fueled, on the road a mere twelve years from now.

How far have we come in the last twelve years? 2006 was just before the big runup in gas prices to over $4. Biking was on the rise but had almost reached the plateau. Vehicles have gotten a *lot* more fuel efficient than in 2006 … there was a drop in driving soon to come, but that was due to the economic collapse. Now we’re collectively driving more than ever.

In the next twelve years will we run short on oil, triggering a jump in prices that would make things change fundamentally? No. The oilfield exploration and development of the last twelve years will keep that from happening.

In the next twelve years will we have a climate change-caused disaster on such a scale, with so much human suffering and displacement, that millions of Americans decide to make changes to their lifestyle in response? Possible, but unlikely. The water’s getting closer to boiling, but there’s not much likelihood we’ll jump out of the pot.

In the next twelve years will we have self-driving cars? Yes, but. Probably they’ll be commonplace – maybe as common as EVs or even hybrids today – but with the average age of vehicles on the road being (coincidentally) 12 years, most cars will still be human-operated.

In the next twelve years will we abandon 100 years of buying cars to represent our personalities and project our status to the world and give ourselves a futile sense of control in a world that’s out of control, switching from an ownership model to a shared model? Hahahaha. Get real.

If anything, we’re likely to be facing the same battles: a tragedy of the commons with congested roads where more cars crowd the streets than their capacity, due to ongoing subsidies and fuel being cheaper than it would need to be to actually ration use properly. Still arguing about fuel taxes, still debating global climate change and what to do about it, bike and transit modeshare higher but still below the critical threshold to make them truly safe enough (in the former case) or convenient enough (in the latter case) to seriously compete with the automobile.

“How far have we come in the last twelve years?”

The most interesting trends are non-linear.

We appear to be entering what some have called runaway climate change, where positive feed backs become unstoppable. Have you checked what is going on in the arctic recently?

The fact that we’ve had a fossil fuel bonanza for more than a century is no indication of how quickly the (economic, environmental) end may come about.

“In the next twelve years will we abandon 100 years of buying cars to represent our personalities and project our status to the world and give ourselves a futile sense of control in a world that’s out of control, switching from an ownership model to a shared model? Hahahaha. Get real.”

This is one of the most common misunderstandings of this issue here.

You are focused on preferences; I suggest we pay attention to constraints.

I’m not convinced, like you, that a sudden imposition of the constraints you talk about is imminent. We’ll let the water keep simmering. Of course I’ve been paying attention to what’s going on in the Arctic. But most people either aren’t, or don’t realize how it relates to their individual lives.

What’s the mechanism that would suddenly cause people to abandon their desire to own the vehicles they travel in – let alone abandon the concept of traveling in individual vehicles? Doubling of fuel prices? That will certainly cause a lot of people to drive less, and some to give up on vehicle ownership. But not most: I think, as someone who’s voluntarily given up driving, you fail to realize how much emotional investment people make in their cars, and the way automakers market to our so-called “reptilian selves” to get us to spend way more than necessary on their product.

America has a pretty dispersed populace, too: many tens of millions live in places that can’t, and won’t, easily be served by bike and transit for the majority of their trips. An enormous migration will be needed in order for many people to continue participating in the economy. That will take time. Trillions of dollars of property value are tied up in suburban homes, and it will take many years for people to write off their losses, accept reality, change jobs to be closer to home and/or move to cities closer to their jobs, but which will have suddenly gotten staggeringly expensive to live in.

Even if gas went to $20/gallon abruptly and stayed there indefinitely, that change won’t happen even over a 10 year period. Most people will keep driving, at least for a few years, albeit putting on far fewer miles and in the most economical vehicles possible. This will of course mean they will continue commuting into increasingly crowded cities, and will probably need to rely on public transportation for part of their commute; but they’ll still need cars for that good old last-5-miles problem.

“…cause people to abandon their desire to own the vehicles … how much emotional investment people make … “reptilian selves” to get us to spend way more than necessary…

Those are all preferences, not constraints.

I am under no illusion that people will be predisposed to give up their cars they’ve grown attached to. I absolutely get that, can relate.

But my point is that there will come a time when constraints take over, and those desires, emotions, attachments won’t hold sway, won’t carry the day.

“…many tens of millions live in places that can’t, and won’t, easily be served by bike and transit for the majority of their trips.”

That’s what the Cubans thought too. Until they entered their Special Period. We lived in most of those far-flung locations before cheap fossil fuels. We’ll figure it out. No one’s saying it will be easy or that the transition will happen overnight.

“Trillions of dollars of property value are tied up in suburban homes, and it will take many years for people to write off their losses, accept reality, change jobs to be closer to home and/or move to cities closer to their jobs, but which will have suddenly gotten staggeringly expensive to live in.”

Preferences again. What I hear you suggesting is that what matters is what people will stand for; I’m arguing that what will matter soon is what options we will no longer have at our disposal.

“Even if gas went to $20/gallon abruptly and stayed there indefinitely, that change won’t happen even over a 10 year period. Most people will keep driving, at least for a few years, albeit putting on far fewer miles and in the most economical vehicles possible.”

It will be rough. I think we agree. Elasticity of demand will be worth watching.

There’s nothing in that list about rail transit so by implication that’s not in the plan. A fixed bridge is better for transit operations but it would have to be a bit higher.

In 12 years, the area population will be perhaps 50% larger (unless we’re still recovering from a major earthquake), it’s possible that unstable ice sheets will push a couple extra feet of tide up the river, most vehicles will be electric and perhaps a bit smaller. Unless there’s been a major realignment of parties a Republican will be president.

We should get this bridge shovel ready (sorry) just in case some foible of national government puts a little extra money into infrastructure.

Perhaps the best planning “for the worst” would be to have the City take over responsibility for one of the Willamette’s older arterial bridges so as to divide up the County’s responsibilities among an additional entity…just in case the process/planning/ funding stalls at the County level…placing your eggs in than one basket.

[Plus there should be a disaster management plan for multimodal access to the Fremont Bridge (Cook/ Kerby to Slabtown) if many of the other bridges “go down”.]

Slabtown–is that a funny?

Probably what’s been decided is who’s going to control access to the bridge(s) afterwards

Should make it bikes only E/W, W/E and in both directions underneath. Much cleaner and safer than cars and boats.

Here is an alternative to consider.

Suppose, instead of spending close to $1 billion to build a full capacity, many lane bridge that carries normal traffic volumes of car, bus, freight, bike, ped, rail, etc and that will survive the “big one” earthquake – suppose we instead spent $50 million to build, store, and have ready an emergency floating bridge that is merely two lanes and will carry just emergency and critical traffic for a couple years after the big one.

Because we don’t know if the big one will be next year or in fifty years. If its fifty years, we don’t know how much and what kind of traffic we will need to carry in fifty years. We don’t know if the $1 billion bridge built in 2025 will be the ideal bridge for 2075. Maybe it will be better to simply build the right bridge at that time.

We do know that, for years after the big one, life in Portland will not be back to “normal”. There will not be the normal daily commuter flows over the river for a long time, for years when downtown, the freeways, the roads, water, sewer, etc are being rebuilt. So the emergency bridge will serve the immediate need, while we build the right bridge for 2075 – hopefully with all federal money 🙂

In World War 2, the military carried sectional pontoon bridges that could span the big rivers of Europe and carry heavy armor, trucks, artillery, troops. I expect we have such equipment today.

Indeed we do. Watch Marine combat engineers place a temporary bridge across the Colorado River.

https://www.popularmechanics.com/military/a28446/marines-build-bridge/

We should instantly spend five million studying this idea!

I wonder if there are barges stashed somewhere that could be used for such a bridge? It would have to be in a place where the banks are fairly low, possibly just south of the Hawthorne Bridge. Of course there might be a collapsed freeway on the east side to get past.

Making the Burnside earthquake resistant (proof?) would certainly be a better use of regional transportation funds than adding a lane to I-5 thru the Rose Quarter. About 1/2 Billion for each at this point. Shift the I-5 $ to this key bridge AND remove I-5!

I do wonder if ODOT, PBOT and Multnomah county are talking to each other…apart from Metro’s JPACT.

But how about not spending money to make the Burnside Bridge earthquake proof, and spending that nearly $1 BN on other priorities (affordable housing, seismic retrofit of existing housing, safer streets for ped/bike, and more transit).

Then when the Cascadia earthquake finally hits, whenever that is, using the emergency bridge to meet immediate critical transport needs, and building the replacement bridge that is appropriate for the Portland of that future time. Maybe in 50 years, we’ll have fewer cars. And maybe, there won’t be a need to build the replacement bridge to survive a Cascadia quake . . . since that quake only happens every couple/few hundred years or so.

Between the Burnside Bridge and the I-5 project, that could be $1 to $2 BN that we could spend on other priorities.

P.S. The very rough costs I’ve seen talked about for the new Burnside Bridge is $400 to $600 MM. I figure that with the usual cost overruns, that could end up being closer to $1 BN.

If we take that illustration of a broken bridge as written, I wonder what you would see if you could scroll around central Portland? We can get some idea of what happens after a disaster by looking at Kobe, New Orleans, Christchurch, etc. Part of our preparation can be “build stuff” but a lot of it has to be resiliency. My quick take? Our possible damage is going to be like Christchurch, or even worse, Kobe, but the recovery process is going to be more like New Orleans. Japan responded to a 2.6 % drop in economic activity after the Hanshin earthquake with a recovery effort that ramped up the economy by 3.4 %. Our national government is making a science of disfunction. I don’t think we can count on that kind of response.

I believe Portland could get hit a lot harder than Kobe (a city, which incidentally, I had visited a mere nine days before the Great Hanshin Quake hit there, so I have a little familiarity with the place).

That was an M7 quake. Portland is due for an offshore M9.5, which would shake at least as hard as a local M8 – to which Portland is also susceptible, should the West Hills fault slip again.

Although the Kobe quake – which killed 5,000 people – exposed a lot of weaknesses in Japanese construction practices, their buildings were vastly more resilient than Portland’s. I fear the devastation in Portland (and Seattle, and Vancouver BC, and every smaller city west of the Cascades) will dwarf what happened in Kobe by an order of magnitude.

It will be by far the largest-scale natural disaster in US history (unless half of Florida and many major coastal cities start going underwater due to rising sea levels by then), and a massive rebuilding effort will probably be beyond the resources of even the US government. I think X is right that Portland has to do what it can now to ensure resiliency. Having more than one Willamette River bridge standing after the Big One (that would be in addition to the Tillikum) would be a really good thing.

And I’ll plug my proposal one more time: knock down the Marquam before the quake does it for you.