(All images courtesy Metro)

Written by Metro Parks and Nature Department Senior Planner Robert Spurlock. Robert is also a member of the Oregon Bicycle and Pedestrian Advisory Committee and the Oregon Recreation Trails Advisory Council. This post first appeared on Metro’s Outside Voice blog.

A thriving metropolis at the confluence of two major rivers.

A world class bike path in the heart of the city, built over the water to bypass a tangled mess of highways and train tracks that had historically cut off the city from its river.

What I see as the most important lessons to be learned from our peers across the country, as well as what we already do well and should continue to do.

A stated vision of an interconnected bi-state network of regional trails spanning 750 miles.

And a coalition of dozens of public, private and nonprofit organizations championing the network’s completion.

This probably sounds like Portland, the Eastbank Esplanade and The Intertwine Alliance. But, in fact, I’m talking about Philadelphia, the Schuylkill Banks Boardwalk and the Circuit Trails coalition.

This past March I represented The Intertwine Alliance in Philadelphia at a gathering that brought together leaders from 20 regional trail networks around the country. For two days we shared our successes and challenges, compared notes, and discussed a shared strategy for moving our trails agenda forward at the national level.

Similarities between The Intertwine and Philadelphia’s Circuit Trails are striking, as are the similarities with the other 18 regional trail networks represented at the event. But we can also learn a lot by looking at what we each do differently. Each network has achieved success in its own way, with no two regions following the same blueprint. In this post I will describe what I see as the most important lessons to be learned from our peers across the country, as well as what we already do well and should continue to do.

Common Ground

Each regional trail network articulates its vision, values and benefits along more or less the same lines: Trail networks create livable regions where diverse communities can live healthy lifestyles with easy access to nature and freedom from car traffic.

(Photo: Jonathan Maus)

We all see trails as a panacea to promote wellness, equity, conservation and economic development, while addressing road congestion and climate change. What else do all of our regional trail networks have in common?

- From San Francisco to St. Louis to South Carolina, regional trail networks are adapting to become more representative of communities of color and historically marginalized people.

- The wild success and popularity of a new trail when it opens is a common story heard from all corners of the country.

- The insatiable public demand for more trails is being felt everywhere.

Not to say that all of our commonalities are positive: The initial backlash against trails from immediately adjacent neighbors is a challenge no region is immune to; Struggles with railroads and frustrations with byzantine state DOTs are universal; and we even had a good laugh over our shared wish that spellcheck software was capable of catching our profession’s most common typo, “trial.” That’s trail nerd humor, I suppose.

But the perennial issue at the top of everyone’s mind is funding. In one of our many group discussions, we all asked ourselves, is current funding adequate to deliver the ambitious visions we’ve laid out? With the cost of new urban trails approaching $3 million a mile, not to mention $10,000 per mile per year in maintenance, for many of us the answer is no. There is growing interest in tapping new funding sources, and public-private partnerships are increasingly becoming the preferred model for project delivery in many communities.

Advertisement

The Rise of Private Funding for Trails

Local governments can’t do it all.

In a 2015 Outside Voice blog post, Katie Mangle and Mia Birk point to Indianapolis and Northwest Arkansas winning TIGER grants worth $20.5 million and $15 million, and note that this success with federal transportation funds wouldn’t have been possible without millions of dollars in private foundation contributions.

Indeed, several other communities are having success leveraging TIGER and other federal funding streams with large corporate and philanthropic donations. Philadelphia’s aforementioned Circuit Trails network is a good example of this trend, having received $19 million in new funding for trails in 2015, including $4 million from private foundations, which in turn leveraged a $12 million TIGER grant.

Differing Implementation Models

The public-private partnership examples in Arkansas, Indianapolis and Philadelphia represent a new paradigm of regional trail funding models, as more and more regional trail networks move away from a singular reliance on federal transportation funds. To be sure, federal transportation funds remain the primary regional trail funding source throughout the country. But uncertainty about the future of this pot of money coupled with the growing demand for more trails has many communities looking to grow their funding pie with a diverse array of new sources.

Non-federal sources aren’t limited to private funds, as state and local funding for trails also play major roles in many communities. So far, the Portland region has barely tapped into private funding for trails, and our public trail funding remains overwhelmingly dominated by federal funds. So let’s see what we can learn from our peers elsewhere in the country:

- The Carolina Thread Trail, a nonprofit network covering 15 counties and 88 local governments, has given out $4.9 million to local governments for trail completion projects. Corporate sponsorship plays a huge role in the Carolina Thread Trail’s success, with a capital campaign that has raised over $16 million from donors such as Bank of America, Wells Fargo and Duke Energy.

- Great Rivers Greenway is a special district in the greater St. Louis area formed by the voters in 2000. It’s funded through a sales tax that raises nearly $30 million a year for regional trail construction and operations. Great Rivers Greenway recently launched a foundation to leverage private funding.

- Spanning 550 miles and 9 counties in Northern California, the Bay Area Ridge Trail is coordinated through a nonprofit coalition of member organizations representing public agencies and private corporations. Individual donations make up 42 percent of the Bay Area Ridge Trail’s budget, with state and corporate funding providing the remainder.

What Model Has The Intertwine Followed?

With few exceptions, the 350-plus completed miles that comprise The Intertwine regional trail network were built by government agencies with public funds.

Tualatin Hills Park & Recreation District, Portland Parks & Recreation, North Clackamas Parks & Recreation District, and the State of Oregon have been the biggest players to date, with several smaller cities pulling their weight as well. I conservatively estimate that federal transportation funds comprise at least two-thirds of our trail investments, with local funding from bond proceeds, tax increment financing and system development charges making up the bulk of the remainder. Nonprofit coalitions and private funding make up a relatively minor share of The Intertwine equation. And yet, despite our disproportionate reliance on federal transportation funds, we’ve managed to be very successful at building out a regional trail network.

Where Do We Go From Here?

Going forward, I’d like to see the Portland region diversify its trail funding model, with The Intertwine Alliance playing a central role in the effort.

In Philadelphia it was clear to me that our peers in other cities look to The Intertwine as a model to be followed. The Circuit Trails and the D.C. area’s Capital Trails Coalition were both formed in the last five years and cite The Intertwine as early inspiration.

Let’s not take this national recognition for granted; let’s instead capitalize on it to attract corporate donations akin to the hundreds of thousands of dollars REI has donated to the Capital Trails Coalition, the Bay Area Ridge Trail and other urban trail efforts. Most importantly, let’s take note of and expand the modest non-governmental success stories we do have:

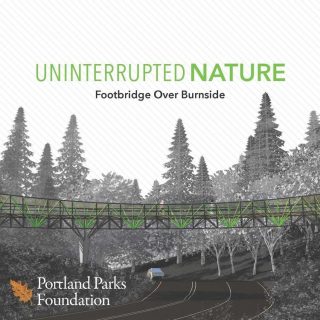

- The Portland Parks Foundation recently raised hundreds of thousands of dollars in private donations to build the Footbridge over Burnside.

- Trailkeepers of Oregon has emerged as the premier trail stewardship nonprofit in the Portland region, having logged thousands of volunteer hours to maintain and rebuild some of Oregon’s most cherished public trails.

- The recently formed Oregon Statewide Trails Coalition is charging ahead, building on the success of last fall’s Oregon Trails Summit with a bigger and better event planned for this fall.

- The steady determination of volunteer advocacy groups like the 40-Mile Loop Land Trust, npGREENWAY and SW Trails keeps local governments on the hook to deliver big, difficult urban trail projects.

And many others.

It’s an exciting time in the world of trails, both local and nationally. The collaboration we started in Philadelphia last month will pick back up again in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, this June, where five Portland-area delegates will represent The Intertwine Alliance at a regional trails conference hosted by the Rails-to-Trails Conservancy. I won’t be joining them in Milwaukee, but I’m eager to hear what they learn and to incorporate lessons from other cities into our work so that we can make The Intertwine the best regional trails network in the country.

If you’re inspired and want to join hundreds of other people who love trails and want to make our regional network better, come to the Eighth Annual Barbara Walker Trails Fair at Metro on June 20th.

— Robert Spurlock

Never miss a story. Sign-up for the daily BP Headlines email.

BikePortland needs your support.

Thanks for reading.

BikePortland has served this community with independent community journalism since 2005. We rely on subscriptions from readers like you to survive. Your financial support is vital in keeping this valuable resource alive and well.

Please subscribe today to strengthen and expand our work.

Philadelphia also allows mixed use hiking/mountain biking trails in City Parks!

Surely there must be daily occurrences of hikers wishing to escape the city to a pristine wilderness only to be run down by out of control daredevils on wilderness destroying machines.

Actually no, those two user groups coexist.

Dozens of public, private and nonprofit organizations coming together….

That doesn’t happen in Portland.

Until the region is effectively able to police the urban trails to remove illegal camping there will be no public support for this type of thing in the Metro area. All the troubles with illegal camping along the Springwater have killed our chance for better non-motorized options for the foreseeable future.

Doesn’t make sense to police until you have a place to put ’em. And Portland doesn’t want to spend money for places to put ’em.

As our housing crisis continues to worsen we will, sadly, see more camping in Portland because most houseless folk are people who were evicted from their homes in your neighborhoods.

https://www.nlchp.org/ProtectTenants2018

>>> most houseless folk are people who were evicted from their homes in your neighborhoods <<<

[Citation needed]

73% of houseless people had housing in multnomah county prior to becoming houseless.

https://multco.us/multnomah-county/news/2017-point-time-count-more-neighbors-counted-homeless-2015-more-sleeping

but you know this well because i’ve shared this statistic with you many times.

I couldn’t find that statistic in the document you linked to, and without context, it’s impossible to know what it means. Did people lose housing because it became too expensive, because of mental or physical illness, because of addiction, or because they ran away from home? No one deserves to be homeless. of course, but these different populations need different solutions.

“ran away from home”

“mental illness”

“addiction”

It’s certainly easier to demean housing insecure folk instead of acknowledging that a lack of stable and affordable housing for wage-earning folk is the primary cause of houselessness.

https://www.nlchp.org/ProtectTenants2018

Sorry — mental illness and addiction are not demeaning (nor are kids who run away to escape abuse). They are serious problems that demand a serious solution.

Where did your 73% number come from? The 2001 number you cite is only 40%.

Have you ever considered that mentally ill people might also lose housing because it is too expensive?

Also, associating homelessness with mental illness and drug addiction is demeaning.

Are you saying there is no connection between homelessness and untreated addiction/mental illness? Or only that it is demeaning to acknowledge one exists (in many cases)?

Homelessness is a very complex issue, and reducing it to a simplistic formula is unlikely to help us find a solution (or, really, a set of solutions).

From the report you linked to: “People who were unsheltered reported high rates of mental illness (44.8%), physical disabilities (38.0%),

substance abuse disorders (37.5%) and chronic health conditions (26.3%).”

“Or only that it is demeaning to acknowledge one exists (in many cases)?”

People with health issues also deserve access to affordable housing. Centering our chronic housing crisis on mental health or addiction smacks of prejudice..

I don’t center the homeless situation on any single cause; there are many different interlocking and overlapping problems that need to be solved. And yes — of course — people with health problems need housing. Who could possibly think otherwise?

seems pretty centered to me. also stereotypical.

i don’t think providing needed housing is particularly complex.

You misunderstood. I was saying that without context your statistic was meaningless. Almost everyone had a place to live before they became homeless, regardless of the cause.

If the solution were easy, we’d be doing it already. We can’t even get people to agree to stop tearing down affordable rental properties, never mind build more.

Did Philly copy our filling-loosening bumps to get on their floating bikeway?

At what point do we start to treat car-free bike infrastructure as essential transportation infrastructure with similar level of service and adequate detours during closures? The same “constituency syndrome” that causes politicians to treat bike lanes as nice-to-have also gets us the parks dept managing our bikeways as if we would be just as well served by riding several miles in the opposite direction or around a lake a few times. People who are trying to do us the favor of replacing their car trips by biking should be given a beer and a push up the hill rather than a stick in the eye and a shrug while extra car lanes go mostly unused.

The role of private funds/corporate contributions really struck me. Given our mecca for sport/ outdoor wear and gear industry you would hope we could do a better job of getting our local corps to step up to the place with sponsorship dollars and funds to match federal/state dollars. I recall this being a distinct disadvantage for Portland’s application for the Smart Cities grant as well (we couldn’t come up with the promised matching corporate dollars that other large cities could). I appreciate that Nike stepped up to the plate for bikeshare. Granted trail funding doesn’t have the branding opportunities, but I couldn’t mind some ‘sponsored by’ signs along a MUP if it helped to get it built!

Philadelphia has had better dedicated trails and path networks than Portland for years. They close a major street every weekend for recreation. They also tax and spend money on these things instead of just complaining about how hard everything is.

The River Valley Alliance in Edmonton is a good model for Portland to follow. Still the best urban river trail network I’ve seen.

https://www.edmonton.ca/activities_parks_recreation/parks_rivervalley/river-valley-trail-maps.aspx

http://rivervalley.ab.ca/

My first reaction on reading this was: Portland has a regional trail “network”? Yes, we have some decent extended paved multi-use trails and we have extensive natural surface trails in Forest Park and other areas (although the vast majority are restricted to one use – hiking). But if you look at the map on the Intertwine’s website and select “trails”, it is very obvious that connectivity is a big problem. We have a long way to go if we want to get to the level of off-street trail distance + connectivity of places like Denver/Boulder and Minneapolis.

Also, I lived in Philadelphia for two years and loved the fact that I could ride from my apartment in Center City along a 4 mile paved trail to Wissahickon Park, then ride 14 miles of mountain bike trails, and return home. The whole trip only required me to be on the street for about 1/2 mile total.