This is a guest post by Kiel Johnson.

A specter is haunting our cities — the specter of street life!

Our streets make up the vast majority of our public space in cities. How these spaces are designed have profound impacts on how we think about communities and the policies we create. Janette Sadik-Khan’s “Streetfight: Handbook for an Urban Revolution” is a necessary chronicle and persuasive argument for giving street space back to people. She writes “streets are the social, political, and commercial arteries of cities … These are the spaces where life and history happen.”

Last week, I presented to a group of business leaders in the Lloyd District, most of whom commute by car from the suburbs. I was talking about the Better Broadway project that will open one auto lane of Broadway up for businesses and people for one week next month.

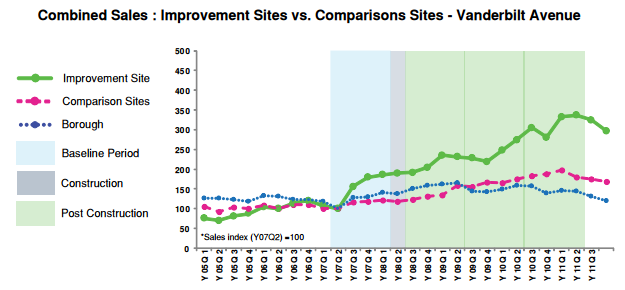

To make my case, I referenced a report that Sadik-Khan’s New York City Department of Transportation put together using tax receipt data to compare streets that had added bike lanes and pedestrian plazas and reduced speeding by better coordinating the space dedicated to cars. In most cases, the streets that had been transformed saw more business.

Surprisingly, at the end of my presentation no one screamed that I was possessed by the devil, hell-bent on destroying everything good in the world. Through this book and her work, Sadik-Khan has given street fighters the weapons to transform our streets: data and success stories. That is the strength of this radical and revolutionary book.

Advertisement

Sadik-Khan’s well-written book has much to offer to the way people think about and design streets. She writes:

Cities must adopt a more inclusive and human approach to reshaping the urban realm and rebuilding it quickly to human scale, driven by a robust community process, but committed to delivering projects and not paralyzing them. Reversing the atrophy afflicting our city streets requires a change-based urbanism that creates short-term results – results that can create new expectations and demand for more projects.

If we want a more inclusive community with policies based on compassion instead of fear, we need to build public space that fosters compassionate interactions, not walls of freeways that encourage solitude.

“Streetfight” weaves the narrative through Sadik-Khan’s experiences as NY Transportation Commissioner from 2007 to 2013. Each tale of urban renewal begins with the forces fighting “any change to the urban context” but ends with their defeat at the hands of strong leadership and enlightening data.

In the New York Post’s review of “Streetfight,” titled “How Janette Sadik-Khan Ruined Our Streets,” frequent Sadik-Khan critic Steve Cuozzo unknowingly makes the case for the book he does not endorse:

Our eyes tell a different story. … In nearly every case, just about the only riders most times of day are food delivery people. While a boon to Upper East Siders who might have a shorter wait for General Tso’s chicken, it spells slower progress for the zillion cars, trucks and buses trying to inch their way uptown.

Some people might never be convinced, but this book once and for all eliminates the argument that Steve Cuozzo’s eyes are the best metrics for urban planning.

While the book is full of acknowledgements and “thank yous,” Sadik-Khan’s recollection of the then-Portland-based Alta Bicycle Share is much less rosy. She says it was an “ordeal to keep the program from collapsing and rescue it from the self-inflicted wounds of its own management.” From a failure to secure funding to technology disasters, the rollout of New York’s bike share faced repeated delays. She sums up the experience by saying “they were either out of touch with the truth or had no concept of how to conduct the public’s business in New York City.” Ouch.

While there is a lot of inspiration to be drawn from this book, by the end your biggest hope is that Sadik-Khan will become your city’s next transportation director. The amount of resistance that had to be overcome to create change seems daunting. I frequently fantasize about what Portland’s Transportation Director Leah Treat’s book would be called. Perhaps “Give Me Street Fee Or Give Me Death”? Or “Portland: A Once Notable City That Removed A Highway A Long Time Ago”? I hope that this book does not sit on the same shelf as the Portland Bike Plan.

Sadik-Khan’s victories show that success can only come by taking big risks. The only things we have to lose are ugly, expensive parking lots. We have a world to win!

—Kiel Johnson is the owner of Go By Bike, the bike shop and free valet operating in the South Waterfront neighborhood.

Thanks for reading.

BikePortland has served this community with independent community journalism since 2005. We rely on subscriptions from readers like you to survive. Your financial support is vital in keeping this valuable resource alive and well.

Please subscribe today to strengthen and expand our work.

That poses a good question: is Leah Treat just not as good a leader as we need, or is there something about the PBOT structure that prevents her from living up to her full potential? Everyone I’ve met from PBOT talks a good talk, but results have been lacking.

I think we need elected leaders who understand the issues and make livable streets their priority.

Was just gonna point that out. Just started reading the book and notice she gives a great deal of credit to then-Mayor (but probably not next President) Michael Bloomberg for having the long-term vision and short-term focus and gumption to help get the right people doing the right jobs.

And nice review, thanks! And yeah, unfortunately there’ll always be the vocal h8ers: http://www.cyclelicio.us/2016/i-havent-talked-about-carnage-in-a-while

One big difference is that we don’t have a strong mayor system. It’s a lot easier to be a great transportation director when you have a powerful elected official at your back.

Beeblebrox,

I hear that excuse so often… especially from people who work at PBOT and City Hall.

And I agree with it somewhat, but also agree that excuses are easy to make. What if we had a strong mayor who was anti-bike? To discount what JSK and TransAlt and the other advocates in NYC did and say it’s really just because of Bloomberg’s support just doesn’t hold water IMO. Portland is good at making excuses and bad at doing the bold things it takes to create good politics.

I have to disagree to a large extent. Political cover is absolutely necessary to get big things done. Without it, ideas die before they get to Council. Not trying to take away from the greatness of JSK, but she would not do as well in Portland as she did in NYC.

Also Leah Treat is not a bureau director in the normal (NYC) sense of the word – her powers to hire and fire workers is severely limited, for example – but rather, as explained by two former directors at her interview (I was there), her job is to be the main PR person between the public, the PBOT bureaucrats, and the elected commissioners. The people who really run PBOT from the inside are the most senior bureaucrats who have “classified” (permanent) positions, while the commissioners can hire and fire any of the at-will “unrepresented” employees, including Treat & Pearce.

Remains to be seen whether Treat is enough of a fighter to get some new ideas in motion. As inspiring as her ideas and efforts have been, I don’t think the strength of Sadik-Khan’s ideas were great enough to carry on over NY city council had the opposition there been overwhelming. It wasn’t overwhelming, because of Bloomberg recognizing some potential good ideas and deciding to run with them, damn the torpedoes.

Downtown Portland and greater Portland isn’t NYC though. Life is easier in Portland, much easier. Traffic in Portland is nothing compared to what it is in NYC, so I hear. Nor is lack of parking. My guess would be that people in the city have been fed up for a long time. They were ready for some dramatic experimental changes to street functionality, even if they didn’t work out. Maybe the catalyst for change among the population, doesn’t exist here, as it did in the NYC.

“I hope that this book does not sit on the same shelf as the Portland Bike Plan.”

Ouch.

I’ve lived in Portland and lurk here from Corvallis, just wondering. . .Why can’t people who live on this forum throw ineptitude out and do a better job for Portland? It would appear to anyone reading here that Portlands government structures are toppled bureaucratic dinosaurs decomposing in place. The so_called “process” appears to just dump more rot onto the heap?

Some of the ideas available through crowd sourced media like this are so much better than various ‘OTs schemes and sloth.

If DT can dismantle/overhaul the former house of Bush someone with great ideas can turn down the meat grinder traffic a notch and get a few miles of trail opened for mountain bikes.

I met some super genius people in Portland and I know you can do better than Austin freakin’ Texas with bikes.

Don’t give up,

RW

I had a quick jaunt up to Portland on Monday for business and picked up an Oregonian from the hotel to read on the plane. Two letters to the editor on the last page were indicative of the Steve Cuozzo mentality: one from Ervin Sierson of NE saying he and his wife were disappointed with what they get for their taxes and listed “Transportation” at the top which he previously related to complaining about potholes, and “Sustainability” and “Livability” he seemed to equate to ‘stop building things for people who aren’t here yet.’ Next up was Susan Ruecker of NE advocating (against Nick Fish) for dogs’ rights to nature, but “No high speed mountain bikes – just people, dogs and wildlife co-existing.”

Here in silicon valley people are quite vocal against bike lanes and any form of road diet, and they are still harassing Santa Clara’s city council about a road diet (Prunderidge) done years ago (that the police say made a dramatic reduction in tickets, speeding, and crashes), and one woman who launched a bike lane removal campaign after getting a ticket (by a bicycle-mounted officer, no less) for driving in one (Hedding) seems to have quieted down a little… for now.

They may be government officials, but they are still led by populist politics.

Some time ago I asked a city “bureaucrat” the difference between an “at-will” and a “classified” employee.

It was hard to get a clear answer, but several years ago the “at-will” category allegedly was expanded. This would lead one to expect that it ought to be easier for a city commissioner to put responsive people in place.

David Hampsten’s comment suggests otherwise.

Does anyone know who the “at-will” people in PBOT actually are?