With Portland’s locally funded Safe Routes to School program seeming to pay clear dividends — biking, walking and rolling to primary school became more popular than driving in 2010 and have kept rising — the case for bringing the idea to other cities may seem strong.

But the For Every Kid Coalition that’s been lobbying the regional government Metro to put $15 million into a regional Safe Routes to Schools program is competing for cash with two major forces: public transit and private freight. As Metro continues to accept public comments on the subject, we wanted to share what its councilors are thinking.

So we called all of them.

Five of the seven people on the Metro council responded. (We left two messages each with the two who didn’t: President Tom Hughes and Councilor Carlotta Collette.) Here’s what we learned:

“We would be making a big mistake if we were to reduce the amount of active transportation dollars.”

— Sam Chase, Metro Councilor

1) This debate is almost entirely about a collection of federal transportation dollars, granted automatically to Metro from multiple sources and rolled into a program called “Regional Flexible Funds.” For the three years from October 2018 to September 2021 — those are the years currently up for discussion, but they’re also sure to be the starting point for future negotiations — it’ll come to about $130 million total.

For comparison’s sake, one mile of sidewalk might cost about $1 million. Portland’s proposed 10-cent gas tax would raise about $15 million for each of four years.

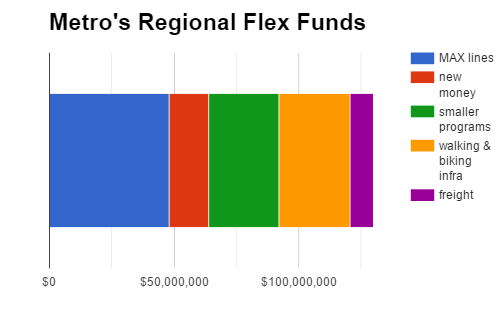

2) This money is probably going to be divided into five different categories. First, $48 million comes off the top to pay down loans TriMet took out in order to build the region’s various MAX lines. Second, about $16 million is being set aside for new purposes; it’s essentially “new money” created by the recent federal transportation bill. Third, $28 million goes to three smaller Metro programs that subsidize dense development, underwrite marketing efforts like the annual Bike Challenge and upgrade traffic signal hardware. Finally, the remaining $38 million is split 75/25 between the last two sources: 75 percent to walking and biking projects and 25 percent to freight-related projects.

Here’s what that would look like on a chart:

3) There will almost certainly be unanimous support on the council for preserving what’s known as “the 75/25 split” in that last pot — that is, the relative width of the orange and purple stripes. “It would take convincing to get me to do something different,” said Metro Councilor Craig Dirksen. “We would be making a big mistake if we were to reduce the amount of active transportation dollars,” said Councilor Sam Chase.

4) Every Metro councilor we talked to is open to supporting Safe Routes to School somehow, but each currently has a different plan for doing so. Councilor Bob Stacey, for example, doesn’t envision greatly increasing the total amount of money going directly to active transportation (he seems inclined to spend the new $16 million on mass transit projects instead) but would support making sure that all $28.5 million of Metro’s active transportation flex funds be spent near a school. Councilor Kathryn Harrington, meanwhile, thinks the new money could be split between school projects and off-road paths.

With over 3,500 messages from their constituents being delivered in support of better biking and walking near low-income schools (thanks to an organizing effort by the Bicycle Transportation Alliance), the Metro councilors are under substantial pressure to deliver something seen as a win for Safe Routes projects.

But they’re also facing pressure to spend money on freight improvements (like time-saving traffic signals near Port of Portland land) and public transit improvements (like the Southwest Corridor rail or rapid bus near Southwest Barbur, or the Powell-Division Corridor express bus).

And at the moment, one or both of those seem to be getting priority on the Metro council. Of the councilors we talked to, only Harrington and Chase seemed to be putting forth plans that wouldn’t simply carve new Safe Routes funding out of other money already being spent on biking and walking.

Advertisement

Here’s more on what each councilor said. Keep in mind that this is all preliminary to their final decisions; we only asked them to talk about their thinking on the issue, not to guarantee their votes.

Kathryn Harrington – represents Hillsboro, Northern Beaverton and Forest Grove

(Photo: Metro)

Freight access issues and other improvements for autos are important, Harrington said, but Metro and the state have plenty of other money that can be spent on them.

“These flexible funds, the heart of these funds is to help build communities and to help people 8-80 move around through our region,” Harrington said. “They only account for less than 5 percent of the overall transportation dollars that we have. … The [federal] FAST Act directs a lot of funding toward roadways and highways that we as individuals take advantage of, but we also have investment needs for transportation options in our communities that help bring communities together.”

Harrington was one of several councilors who brought up the council’s recent “Climate Smart Communities” plan, which sets ambitious goals for boosting biking and walking even faster than it would boost transit. But the plan, she noted, is mostly unfunded.

“Now is the time for us to put the resources behind that agreement,” Harrington said.

Harrington didn’t say she was committed to finding $15 million for Safe Routes, but said she’s receptive to the idea, especially in the areas surrounding the region’s 124 schools where more than half of students are from households poor enough to receive federal aid for lunch. But she wanted to balance that against the continued construction of regional paths like the Council Creek Regional Trail.

Shirley Craddick – represents East Portland, Gresham and Damascus

Craddick backs Safe Routes investment but says Metro more time to study which schools should get biking and walking infrastructure nearby.

“Because we have such a limited source of funds, we need to be able to focus funds wisely,” she said. “What are the least safe intersections that effect children? That’s where we should be focusing on first.”

Craddick doesn’t think that’ll be possible in the current cycle, so any federal funds for Safe Routes would need to wait until 2022.

“This is going to be something that’s going to take a while,” she said. “We need to bring the school districts together; we need to bring the advocates together.”

She doesn’t support any reduction in spending for freight access.

“[The] freight mode is probably as challenging as the bicycle mode,” she said. “We obviously need to focus on our economy and make sure that freight can get around like it should.”

Sam Chase – represents northern Portland and downtown

Chase definitely isn’t opposed to transit spending, but he stands out as the councilor saying most clearly that biking and walking have been underfunded compared to transit.

“We are so grossly short on active transportation goals,” Chase said. “It’s going to take more than 100 years to build out our active transportation goals. We should be able to do it in 30 years.”

That’d take four times the money — more than RFF could offer even if it completely eliminated spending on freight.

“Even if you took it from 75 percent to 100 percent, you’re still at just a tiny fraction of the transportation resources for our entire region,” Chase said. “You’re still looking at just a tiny fraction of resources going to active transportation. So we’ve really got to identify strategies that will get significantly more resources into that transportation solution, which may include approaching voters at some point.”

Chase disagrees with Craddick’s call for a regional Safe Routes plan before money is spent.

“I don’t see a huge need for more process,” he said.

Chase said he’s trying to find a “compromise strategy” that would fund both biking/walking and mass transit.

“I understand that people are going towards transit, and that’s an important priority also,” Chase said. “But we also need to find a new way to bring significant resources into Safe Routes to School.”

In particular, Chase is not a fan of locking up RFF money for 20 years to pay off transit construction bonds; he’d rather just spend money up front but not commit to the loan payments. But he’d bow to the group if others insist on that.

“If the general consensus is that we need a larger amount of resources to prepare projects for the Southwest Corridor, Division Corridor,” Chase said, “then I’m OK with that.”

Bob Stacey – represents southern Portland

Stacey was the one councilor who called us before we called him — he heard that we were working on a story and wanted to make sure he could share his take.

“I am one Metro councilor that’s voting yes for $15 million for Safe Routes to School, and I intend to stick by that as we negotiate the contours,” Stacey said. “I have been so impressed by the strength of their support and by the strength of their logic that I participated in that rally at Metro last week at which they submitted several thousand postcards to members of the JPACT committee.”

Stacey’s suggestion for doing that is twofold: first, he wants to use one of Metro’s smaller programs, the regional travel options fund, to pay for more Safe Routes education programs in schools. This would come out of money currently being spent on other education and marketing programs around the region.

Second, he wants to change the criteria for the existing biking and walking funds to make sure some or all of the projects serve schools, especially ones with many poorer children.

“I can easily envision spending all 75 percent on Safe Routes to School mobility projects,” Stacey said.

Stacey is also deeply opposed to spending future federal windfalls on auto capacity projects, something he said happened in the last few years with minimal political debate.

As for the new $16 million, Stacey said his top priority is to help build the Barbur and Powell-Division transit corridors. (It’s worth noting that both of those would get federal matching funds to improve biking and walking connections to transit.)

Craig Dirksen – represents Wilsonville and southeastern Washington County

Dirksen also chairs the committee of local officials (the Joint Policy Advisory Committee on Transportation) that has direct control over the federal dollars.

“Metro doesn’t really have the authority to override JPACT,” Dirksen said. “The most we can do is if we disagree with it, we have the authority to send it back to JPACT and say ‘try again.'”

He thinks that’s unlikely.

“I have never seen it happen and I would be very surprised if it happened,” Dirksen said. “The way we like to do business is we have conversations with one another and we come to consensus before we vote, so that everybody can be satisfied with what comes out of the discussion.”

Dirksen said he never makes decisions in advance of hearing from everyone, but in general did not seem interested in reducing either transit or freight spending for Safe Routes.

“The mama bird comes back to the nest and there’s a lot of open beaks and only so many worms,” Dirksen said. “As the economy grows and we see greater congestion, greater demand for moving goods around the region and whatnot, we run the risk of starving that option as well if we choose to do something else.”

As for mass transit, he said: “If we want to move forward with these future projects, be they Southwest Corridor or Powell-Division or whatever, we need to find a source for that as well.” Locking up the new federal money for transit bonds, he said, “would be in line with what we’ve done in the past.”

Dirksen seemed open to Stacey’s plan to carve Safe Routes money out of existing biking/walking money, though he might not go as far as allocating all of it for the purpose.

In fact, he said, many potential Safe Routes projects near schools are probably already in Metro’s Active Transportation Plan.

“I would guess that a lot of the projects in there would probably qualify,” Dirksen said.

JPACT’s next meeting is Thursday, March 17. If you’d like to contact the councilors to let them know what you think (whatever it might be) the For Every Kid Coalition has a page to help do that.

Correction 5:21 pm: An earlier version of this post incorrectly described Metro’s support of past MAX construction bonds. TriMet issued the bonds; Metro sends payments to TriMet to help pay them down.

— Michael Andersen, (503) 333-7824 – michael@bikeportland.org

BikePortland can’t survive without paid subscribers. Please sign up today.

Thanks for reading.

BikePortland has served this community with independent community journalism since 2005. We rely on subscriptions from readers like you to survive. Your financial support is vital in keeping this valuable resource alive and well.

Please subscribe today to strengthen and expand our work.

How can the bird fly without healthy muscles, Dirksen?

And how much congestion is parents going to and from schools?

The range of factors affecting development of active transportation infrastructure in the metro area is a lot to mentally absorb, and it’s complicated.

Glad though to see that the metro councilors do have Safe Routes to Schools firmly on their minds. That type of infrastructure is of the character that makes it comparatively easy to persuade people to support, compared to say, ‘protected bike lanes’, a type of infrastructure which I think is one that remains to be widely known and understood.

It would take actual rigorous control of the behavior of drivers which requires a spinal structure posessed by no person in any level of American government.

For a lot of schools in the region infrastructure needs are the greatest obstacle to SRTS and are needed before the in program activities in school can be really beneficial. That said, most of these sidewalk improvements are on local streets which cities should step up and take responsibility for improving. Should METRO really be expected to fund sidewalks on local streets when there are so many needs for bike lanes and sidewalks and crossings of regional roads? Plus once federalized you get about 40 cents on dollar, ties you to federal standards, which makes small sidewalk projects very expensive and less flexible to design. I think we need to find a better way to fund SRTS.

The problem with freight funding is that infrastructure built also tends to benefit private single occupancy vehicles. If we build freight infrastructure it should only benefit freight vehicles. Otherwise that additional capacity for freight gets eaten up by exactly the type of vehicles and drivers we want to discourage.

Yep, build 8in high curbs in the center of the freight lanes.

I believe we call those railroads.

Our local elementary (Ridgewood, Beaverton School District) is one of the few elementary school NOT ON A MAJOR ROAD. Looking at the attendance boundaries, it is eminently bikeable from the immediate neighborhood, and, for the older students, the entire boundary area is bikeable. Yet very few students do ride their bikes. The school has both wheel-breaker and staple racks. One reason might be that so many parents drive their children to and from school, and do not respect that they are driving through a neighborhood. Speeding. Cutting corners on turns. Not coming to a complete stop at stop signs. Not paying attention to pedestrians. Safe Routes to School can’t come too soon here, for all the reasons listed above.

You think Safe Routes to School could actually reduce some of the bad driving you describe happening near Ridgewood School?

On Saturdays, I’ve been riding SW Hawthorne over to Cedar Hills. Nicest, quietest neighborhood for riding, you could ever find. No sidewalks, people walk right down the middle of the street with little vehicle traffic to contend with. No dogs running loose, kids playing with balls that roll out in front of your bike.

If it educates the people driving the children to/from, it might. The neighborhood IS super nice to walk/cycle in. Except just before school, just after school, and when the after-school daycare is closing.

Don’t know that I will, but to get a sense of differences in traffic and driving character, I should go check out the neighborhood during the hours you mention.

It would be interesting to look at the school district’s map for this school, showing where in relation to the school, the kids live, and from that, see what would likely be their walking and biking routes from home to school.

There’s a bunch of apartments just south of Cedar Hills shopping center, where some kids may be living. Mostly single family dwellings around the school, I suppose, but I wonder how many of the kids’ residences are generally on a level plain with the school, rather than down the hill. Also, what is the range of distances kids would have to walk or bike from school.

Is there a home to school walking distance typical of Safe Routes to Schools routes, and much chance of that distance being as far as a mile (approx 20-30 minute walk) in length? Would many kids in this particular neighborhood actually be willing to regularly walk up to a mile to school? By biking, it seems possible that many kids could fairly easily cover distance in a third of the time they could by walking.

All interesting things to think about. Bottom line, I think, is it’s sensible to invest in having neighborhoods be more amenable to walking and biking to neighborhood schools, because parts of routes the ‘safe routes to schools’ program can help alter, likely would be on streets that anyone wanting to walk or bike in the neighborhood, also could use with more comfort and safety than many streets in neighborhoods tend to allow. May be a stretch to hope that many, or even any neighborhood could ever hope to be as supportive of walking and biking, as some college and university campuses are, but that at least some might be able to come closer to that, is an idea that tends to stay on my mind.

Why can’t there be traffic police staked out near schools to ticket phone use, speeding, etc.?