“We’re making plans to be able to provide core emergency response services, but it will be a challenge without the staff that does the work day in and day out.”

— City of Portland maintenance worker

Labor contract negotiations between the City of Portland and employees represented by Laborers Local 483’s Portland City Laborers (PCL) contract have been underway for months to no avail. Now, citing insufficient concessions from the city, PCL workers have made it officials: they plan to strike as soon as next week.

According to NW Labor Press, 630 parks, environmental services and transportation bureau workers are ready to walk out.

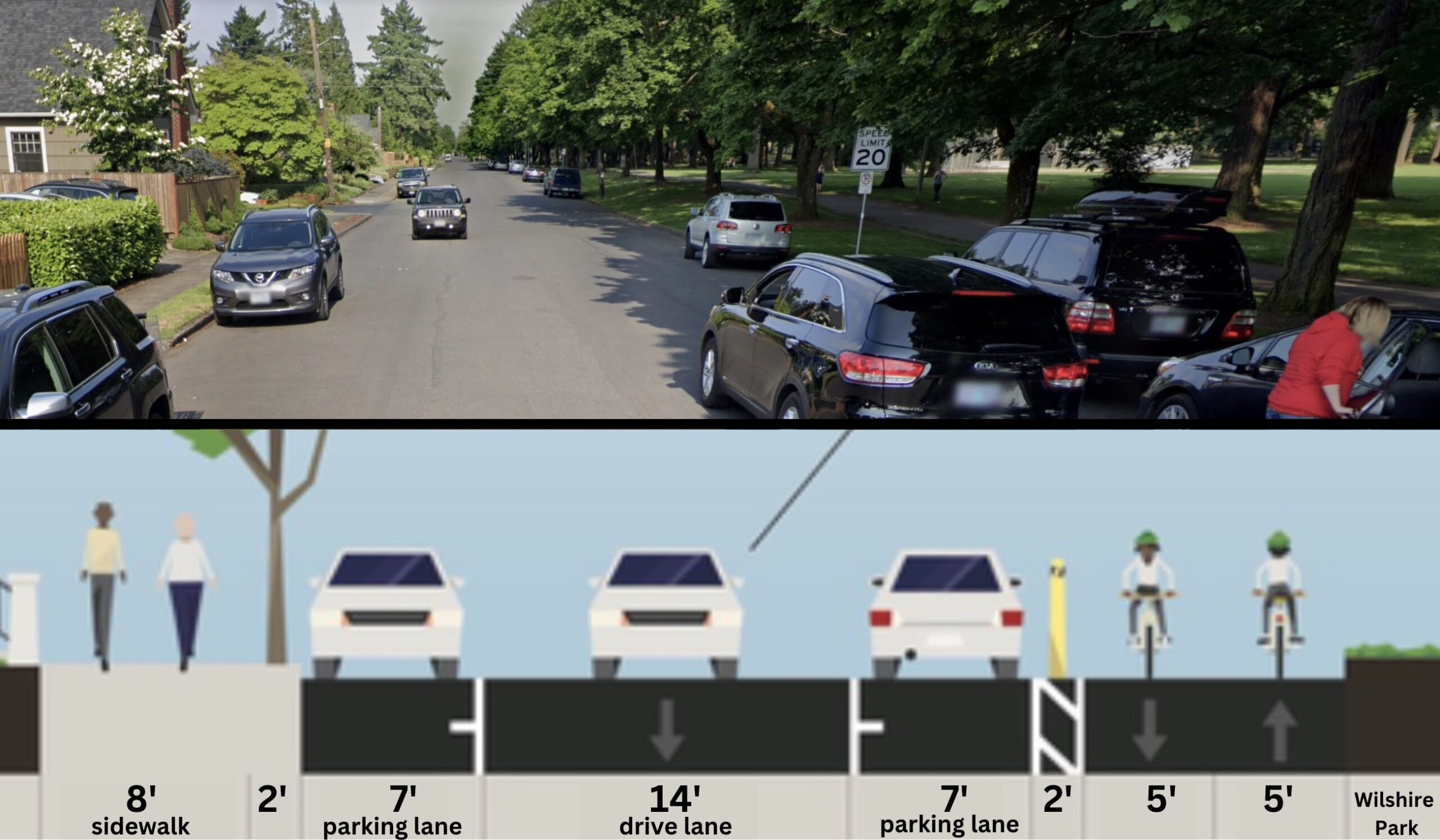

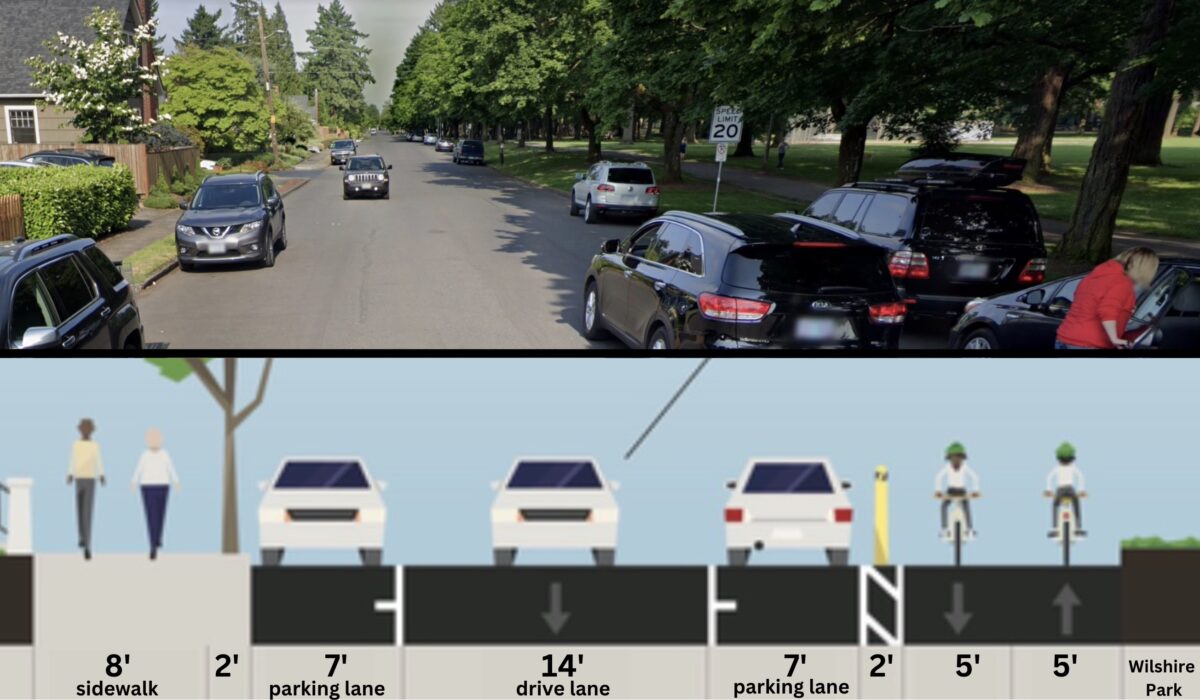

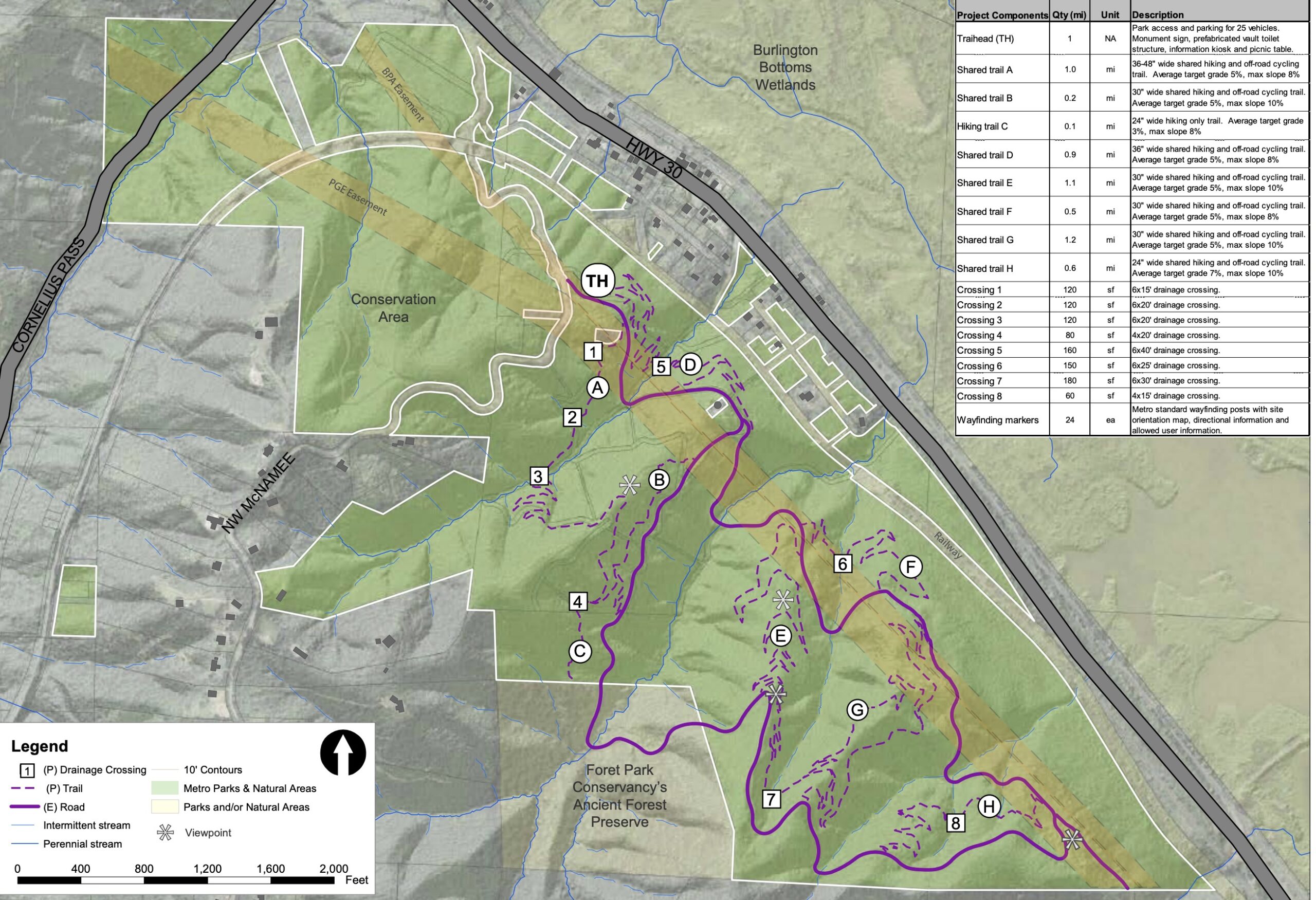

The PCL contract includes Portland Bureau of Transportation maintenance workers who are in charge of street upkeep, striping bike lanes and crosswalks and more. The union says these employees have been working under poor conditions for years now, but the pandemic and subsequent economic inflation exacerbated the situation — and this is getting in the way of their ability to keep up with the very important work of maintaining our streets.

“Union workers under the PCL contract took nearly 2.5 million dollars in concessions at the beginning of the pandemic. They delayed negotiating a new contract for a year to accommodate the City of Portland in its time of need. In response, City decision makers have treated their safety and financial security as a low priority,” a Tuesday press release from Local 483 states. “These workers run our sewer systems, build our roads, maintain our parks, and much more. They are the workers who showed up, in person, throughout the pandemic to keep our City running.”

According to an article posted yesterday by The Oregonian, the City of Portland has proposed a 4-year, $39-million contract with a 12% wage increase by July, which would include a retroactive cost-of-living adjustment (COLA) of 5% and a 1% retroactive across-the-board pay raise.

Local 483 says this proposal is inadequate. The union wants a 3.5% across-the-board pay raise for all members and is asking the city to remove its 5% COLA cap, which doesn’t keep up with inflation. Anything less amounts to a “pay cut” under our current 6.5% inflation rate, Local 483 leaders wrote in a December bargaining update.

They’re not buying the city’s excuses for why they can’t meet those demands.

“The City continues to plead poverty. The PCL Bargaining team has been unconvinced by the City’s argument given the facts as we understand them. Portland’s budget assessment process has consistently “found” tens of millions of dollars, every 6 months, for years,” another recent bargaining update states.

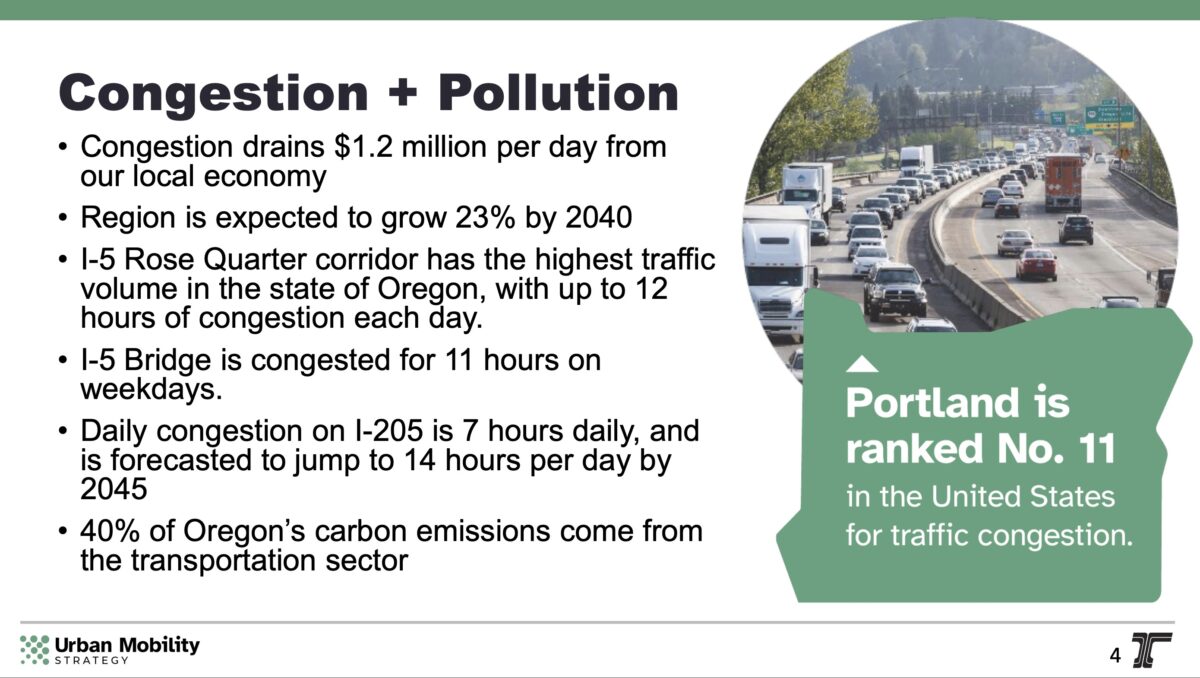

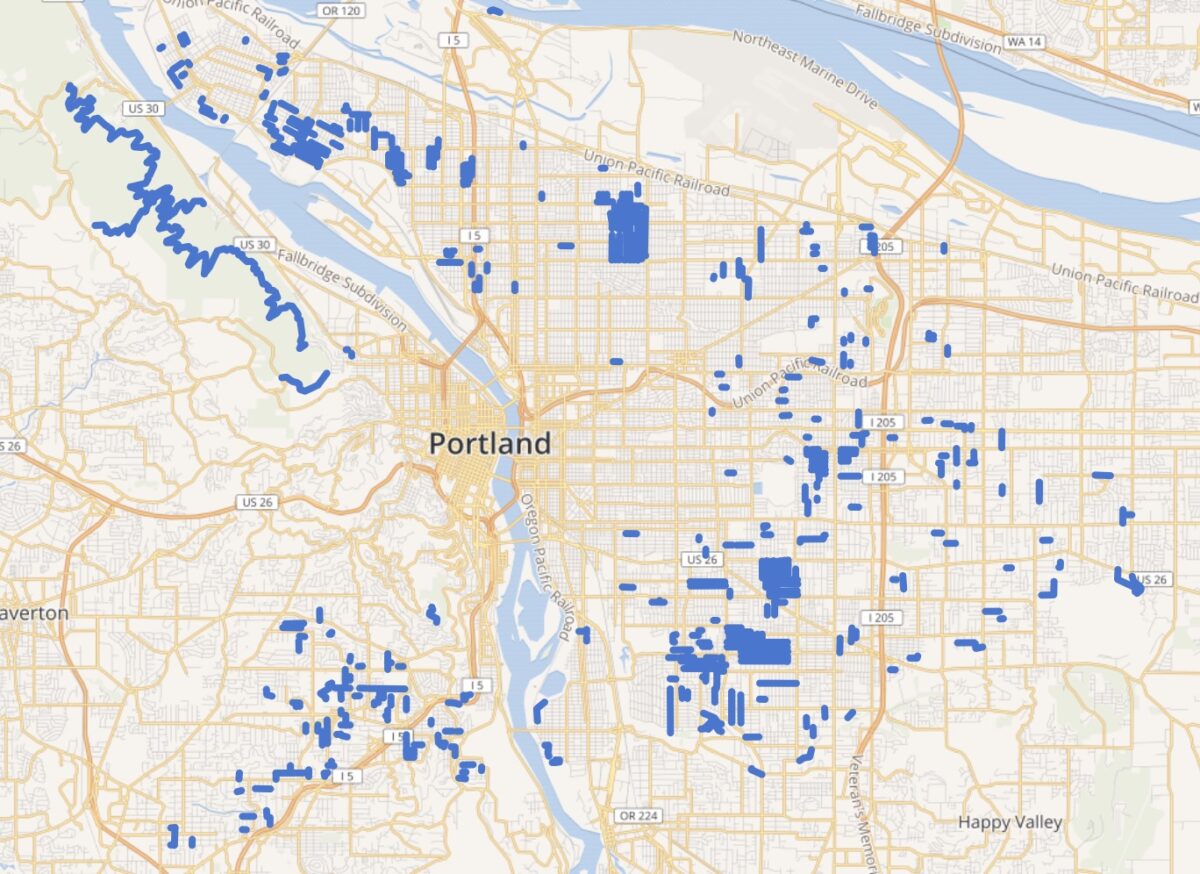

As recent BikePortland stories have touched on, the maintenance issues on our streets have become more and more evident recently — especially for active transportation users. From hazardous, invisible ice on the streets and sidewalks to lake-sized puddles in bike lanes, there’s a lot someone walking or biking needs to look out for when trying to get around the city.

PBOT officials cite the bureau’s $4.4 billion maintenance backlog as the reason they can’t get these problems under control, and say they’re working to develop a new funding structure that would allow them to get ahead of it.

But Local 483 leaders say nothing will change until maintenance employees are respected. And if that means going on strike, so be it.

“We view this contract as an opportunity for the City to honor the sacrifices of workers who have shown up through recent years of crisis. Additionally, money spent on the PCL contract is a sound financial investment. It resources necessary work that provides real value for the people of Portland,” the Tuesday press release reads. “Without that investment, it is likely that the City will see substantial costs associated with the inability to recruit and retain the people needed to avoid catastrophic failures.”

“We’re making plans to be able to provide core emergency response services, but it will be a challenge without the staff that does the work day in and day out,” said one maintenance staffer who spoke to us on the condition of anonymity.

Local 483 will hold a gathering for PCL union workers this Saturday, January 28th from 12 to 3 pm in Terry Schrunk Plaza outside Portland City Hall to ask the city to meet their demands. They invite the public to attend and show their support. You can find out more about the event and the PCL bargaining process at the Local 483 website.

(We have also heard that remaining City of Portland non-represented staffers who aren’t members of Local 483 are planning to form a union of their own. According to the website of the City of Portland Professional Workers Union, 321 non-represented city workers have joined so far.)