“We just need to reimagine what different looks like and what we can do differently.”

-Nafisa Fai, Washington County Commissioner

Transportation agency leaders in Oregon are in a bind. On one hand, it’s necessary to take urgent action to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. But agency leaders know that every step they take in this direction will mean less money for our state’s transportation systems down the line.

As state leaders vote to do things like phase out gas-powered cars by 2035 and advocates encourage people to ditch their cars entirely and take up modes of active transportation instead, the pot of money keeping our transportation system alive is drying up. And it’s happening quicker than they thought it would.

This was the topic of one of the final panel discussions in the Oregon Active Transportation Summit, which wrapped up Wednesday. The conversation was moderated by Hau Hagedorn, associate director of Portland State University’s Transportation Research and Education Center, and consisted of four people who spend a lot of time thinking about the future of transportation funding: Oregon Department of Transportation Chief Economist Daniel Porter, Portland Bureau of Transportation Intergovernmental Resources & Policy Affairs Manager Shoshana Cohen, Washington County Commissioner Nafisa Fai, and Forth Mobility Executive Director Jeff Allen.

The problem

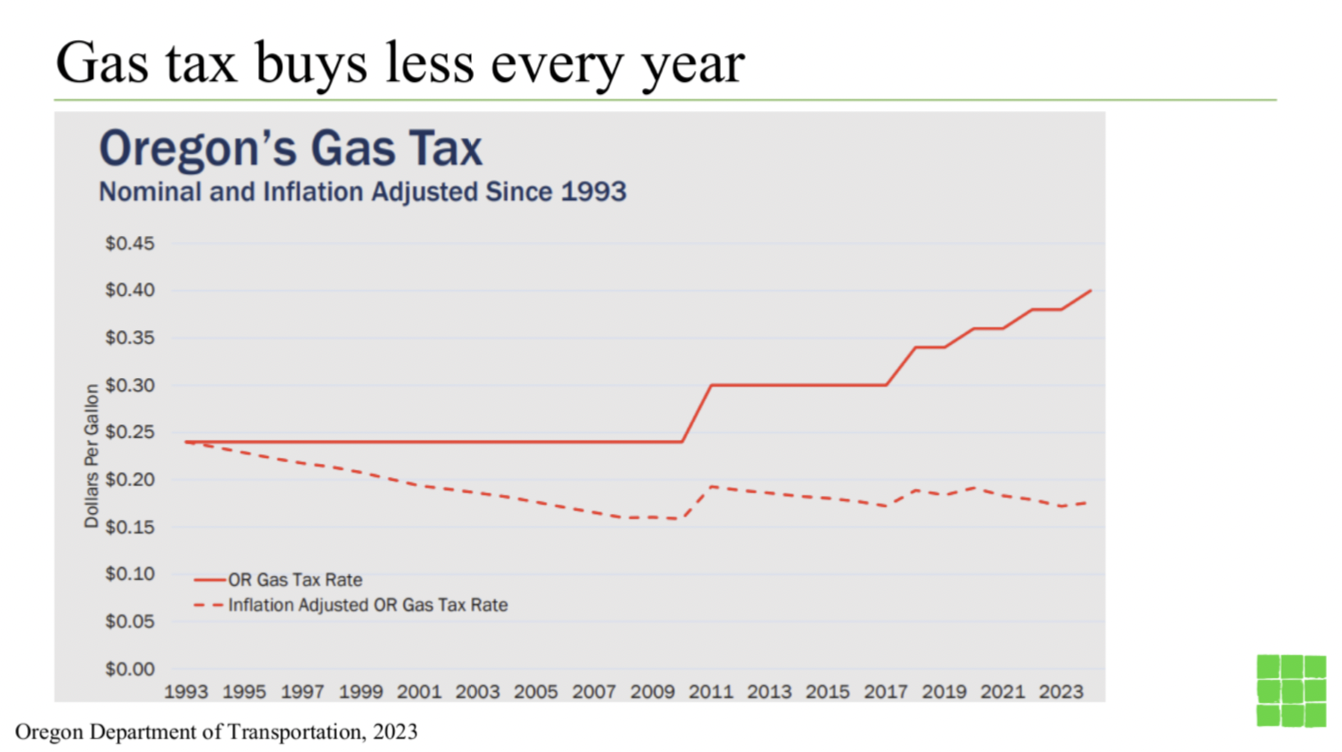

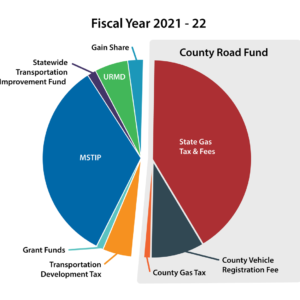

To begin the panel, Hagedorn provided an overview of the problem. Right now, a significant amount of ODOT’s funding comes from its State Highway Fund, which raises money by taxes on gas and diesel fuel, heavy trucks operators and from driver and vehicle registration fees. About 40% of this money is doled out to local governments — so as revenue from the gas tax dries up, cities and counties will face a funding deficit.

Meanwhile, PBOT’s budget is also heavily reliant on the gas tax, as well as parking meter revenue. And when people stopped commuting downtown for work during the pandemic, the agency realized just how much this parking revenue was keeping them afloat — and how quickly it could all be gone. This is a problem, because car parking revenue means more people driving, which is not in step with PBOT’s stated goals to get people out of cars and onto other, climate-friendly modes of transportation.

“The more successful Portland and other areas are at meeting [climate] goals, the less revenue they’ll get to fund the system,” Hagedorn said.

Hagedorn laid out five major reasons why Oregon’s transportation system is in a funding crisis:

- Aging infrastructure across the system

- Growing needs and community expectations to improve safety, equity, climate, resilience outcomes

- Gas tax revenue is declining

- With inflation everything costs more

- Even recent windfalls have not filled the gaps

Porter said that it’s becoming more clear to legislators how urgent the situation is.

“We have visual evidence to show in front of the legislative committee that this is the future, this is what it is. We’re going to have to change something,” he said.

But could this urgency lead to much-needed reorganization and changes within our statewide transportation system?

Opportunities for change

So, what are we going to do about this? One thing leaders know: it’s going to be tough to convince people to pay more taxes and fees.

“There’s fatigue around any new revenue sources,” Cohen said during the panel. “But something’s going to have to change if we want to continue to deliver the transportation system we think Portland deserves.”

Allen, who advocates for transportation electrification at Forth Mobility, talked about how the rising popularity of electric cars contributes to the problem of dwindling gas tax funds. Allen said that over the past few years, he thinks the conversation about transportation funding has morphed into “how are we going to squeeze money out of these latte-drinking EV drivers who aren’t paying their fair share.”

“Some of it is punitive. Some of it is ignorance. But some of it is this is a real legitimate problem — people who drive electric cars do still need to be paying their fair share,” Allen said. “The challenge is how do we do this in a way that doesn’t impair electrification… the opportunity is to create a whole new system of paying for transportation that doesn’t just raise money, but is actually a better system.”

Transportation advocates and officials are anticipating the 2025 legislative session as their chance to push a major transportation funding bill — like House Bill 2017, but better.

Oregon’s House Bill 2017 was a big step for finding new transportation funding sources. The bill included a 0.5% vehicle dealer privilege tax on new car sales (including electric cars) to fund rebates for electric cars and the ConnectOregon program, as well as a 0.1% employee payroll tax to improve public transportation service across the state. But HB 2017 also obligated hundreds of millions of dollars to freeway megaprojects like the I-5 Rose Quarter. We can also thank HB 2017 for the $15 tax on new bike sales, a controversial program that now pulls in about a million dollars annually for bike and pedestrian infrastructure.

It’s not yet clear what this potential 2025 bill would look like, but some people have daydreams about funding the transportation system with road use fees or a carbon tax. And others are asking for a restructuring of what the state currently spends money on.

“I actually believe there is a lot of money for transportation and we are spending it on the wrong the wrong thing,” Fai said. “We just need to reimagine what different looks like and what we can do differently.”

Thanks for reading.

BikePortland has served this community with independent community journalism since 2005. We rely on subscriptions from readers like you to survive. Your financial support is vital in keeping this valuable resource alive and well.

Please subscribe today to strengthen and expand our work.

Given Oregon voters’ long history of doing the exact wrong thing at the wrong time on referendums, I think the most likely scenario will be a statewide measure to roll back state gas tax rates to 1% and eliminate all other fees and taxes on motor vehicles – leading all state, county, and city roads to literally go to pot. On the plus side, this should make driving in Oregon a real challenge.

How about (significantly) raising the cost of meter parking? You’ll get more money and deter people from driving.

Sure we’ll want to explore ways to subsize lower income folks to it doesn’t have as much of a regressive effect. And we definitely make a big investment is transit to make trips shorter and more convenient.

But raising parking costs seems to be a win-win for increasing revenue and reduction of greenhouse gases.

Tic-Tok

“explore ways” is code for lower income people are not a priority and i’ll sock it to them while we study “equity”.

Not my intent.

Just acknowledging that raising parking fees is a regressive hit.

Or even expanding the hours of metered parking could go a long ways.

Just don’t think raising taxes for Multnomah residents is a viable option. We have some of the highest taxes in the nation. You can’t keep saying “tax the rich”. Eventually they will disappear to other locales.

Portland has a relatively modest overall tax burden – comparable to Omaha and Indianapolis.

https://www.chamberofcommerce.org/us-cities-pay-most-taxes

Sorry but I beg to differ. Plus I would wager that Omaha and Indianapolis actually provide functional essential municipal services (police, fire, sanitation, permitting, public health, etc) to their taxpayers.

“Multnomah County has the highest marginal tax rates in the United States of America, but we don’t have the income to support that level of taxation,” said Portland Mayor Ted Wheeler.“

https://www.koin.com/news/portland/report-high-tax-rates-could-be-driving-people-out-of-portland/

This would lower housing costs and make this city a more humane place, so good riddance!

Once upon a time, Portland was willing to talk about imposing a street fee.

Portland City Council needs to start talking about it again. IMHO, a street fee should be put to the people for a vote rather than simply passed by the city council. It also should be designed to (a) prioritize maintenance and safety improvements, and (b) ensure that most of the money raised is spent in the neighborhood where it is collected, and guided by neighborhood priorities.

I expect that “you’ll be paying to fix your neighborhood streets” would be a stronger sell to voters than “all the money goes into a transportation slush fund.”

I was on the TBAC when the street fee was discussed in 2013. The reason it completely failed to gain any traction was the ULF. The Utility License Fee was passed by City Council in 1988 to fund street repairs – any utility company that cuts into the street, both public and private, pays for the cost of repaving that cut, but the repaving is delayed to accumulate enough fees to pay for a street repave or even a rebuild. The rate was set high enough to keep Portland’s city streets constantly repaired for pretty much forever. But guess what happened to the accumulated revenue? Since these funds are not required by law to be used for streets or their intended purpose, City Council then took the funds and spent them on parks, police, housing, fire, and so on – at first it was 20% of the ULF, then 40%, and now it’s 97% – less than 3% actually goes to PBOT. The basic lesson is that any revenue raised by the city for street maintenance has to be in a form that city council cannot legally take away the funds under any circumstances – if they can, then ultimately they will do so, usually sooner rather than later – and so raising the gas tax was the only reasonable and viable alternative given council’s long-term misbehavior.

So in this example, transportation fees are used to subsidize the general fund? This is at odds with the traditional claim that the general fund subsidizes road construction.

My understanding of a “street fee” is that it would need to be spent on streets. I mean, it’s in the name. But one of the reasons to send it to voters for approval is to guarantee in the measure’s text that it can be spent only on street repairs and safety improvements (including paving gravel streets), and not diverted to other stuff (even transportation-related things like bus shelters or streetcar tracks or off-street bike paths). If necessary, ask the voters to put the restriction in the city charter.

We need a weight-mile tax. The increasing popularity of very heavy vehicles (SUVs and electric “cars”) are going to increasingly strain our transportation budget. It’s extremely unfair that someone driving a $100,000, 7,000lb Rivian SUV will pay basically nothing towards road maintenance.

I will vote for that!

Personally I’d support a tax on miles traveled. Please someone make a more catchy name for that lol

ROAD USAGE CHARGE ?

So how does the state keep track of miles driven by Oregon residents. And if said resident drives out of state are they charged for those miles. Every state is trying to figure out how to replace gas taxes for EVs. Texas today just added $200.00 to the yearly registration for EVs. Some have already complained it’s more than what average resident pays in gas taxes. That is one avenue to fund the DOT but is it fair that someone who drives a MINI EV 8,000 miles a year pays the same as someone putting 20,000 miles a year on their Hummer EV.

The state could embed GPS transponders on all its license plates and track mileage that way.

Can you imagine the reaction from people who object to the state mass tracking everyone’s movement? It is probably also a violation of the 4th Amendment, as per recent Supreme Court rulings on the police and GPS trackers.

Yet everyone allows it on their personal phones. Ironic isn’t it?

Indeed it is, though the government at least doesn’t hold cell phone data, and needs a warrant to access it. License plate tracking data would have neither of those (admittedly weak) safeguards.

I don’t think it should matter if your driving out of state or not. I would say charge a fee/mile based on the weight of the vehicle, and assess that fee when a vehicle is registered or you need to get new tags.