Metro is in the process of deciding what will be in the next iteration of its Regional Transportation Plan (RTP), the guiding document that will serve as a 25-year “blueprint to guide investments for all forms of travel” in the Portland area. The plan will include lists of priority transportation projects that are exciting to sift through and daydream about, but the people working on it also must tackle a less glamorous — and often controversial — component: how to pay for them.

A new Metro report delves into how to make sure new funding streams are fair. In the first effort of its kind, the report offers a detailed analysis of key revenue sources and rates them according to an equity score.

Metro hired a team of consultants from Nelson\Nygaard to survey the funding landscape and report back their findings. Out of this process came Metro’s Equitable Transportation Funding Research Report (PDF), which they released last month and have been discussing in meetings and work sessions since.

The research done for this report sought to benefit not only Metro planners, but also policymakers, advocacy groups, and elected officials. It tackles two main questions:

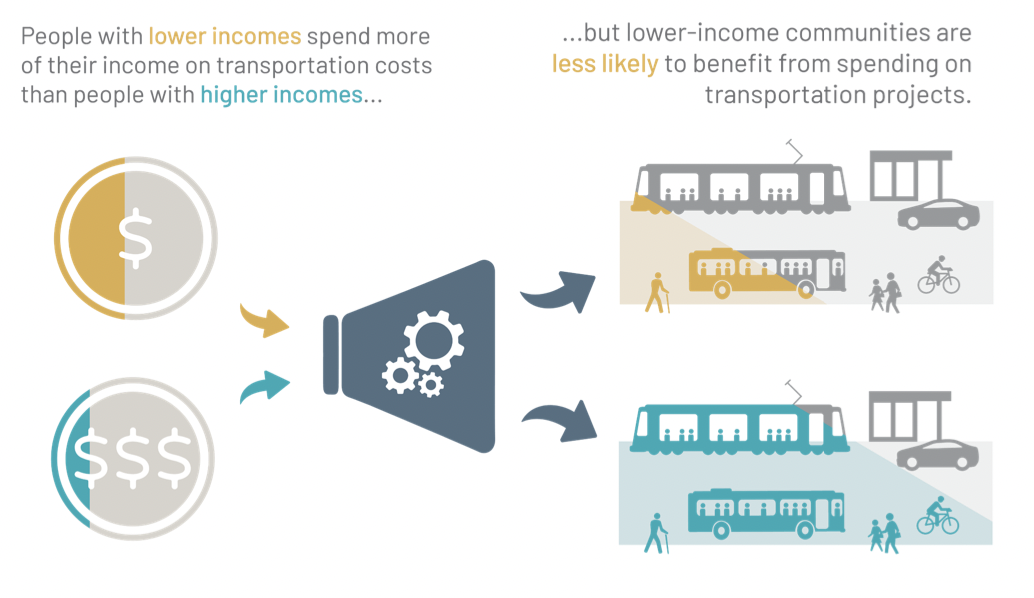

— Who does revenue collection burden and benefit the most?

— How can the revenue collection and disbursement be balanced to address inequities?

History of inequity

“The costs of car ownership comprise a sizeable portion of spending, which suggests that living in areas with less viable transportation options severely impacts financial outlooks, social mobility, jobs access, and other opportunities.”

The report begins with an overview of discriminatory planning in the Portland region. It states that events like the construction of I-5 through the historically Black Albina neighborhood “shaped the context of transportation and land use planning in the region” and that “exclusionary zoning and racial segregation still influence where people live and work today.”

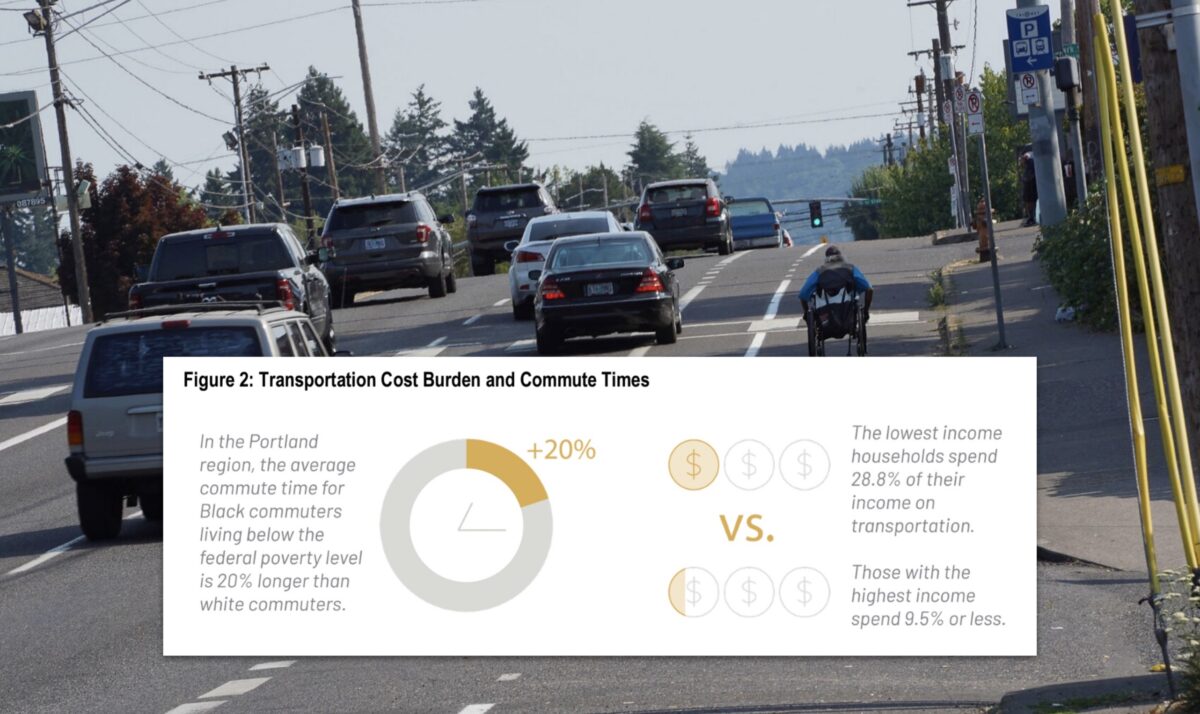

Because of this, it’s more difficult and expensive for people of color and people living on low incomes to get around the city. The report states that in the Portland region, Black commuters living below the federal poverty level have, on average, a 20% longer commute than white commuters do. They’re also more likely to live in areas on the outskirts of town where cars dominate the roads instead of the more expensive walkable, bikeable and transit-dense parts of a city, so they might feel they need to own a car even if they can’t afford to.

“The direct and recurring costs of car ownership comprise a sizeable portion of spending, which suggests that living in areas with less viable transportation options severely impacts financial outlooks, social mobility, jobs access, and other opportunities,” the report states.

Measuring current revenue streams

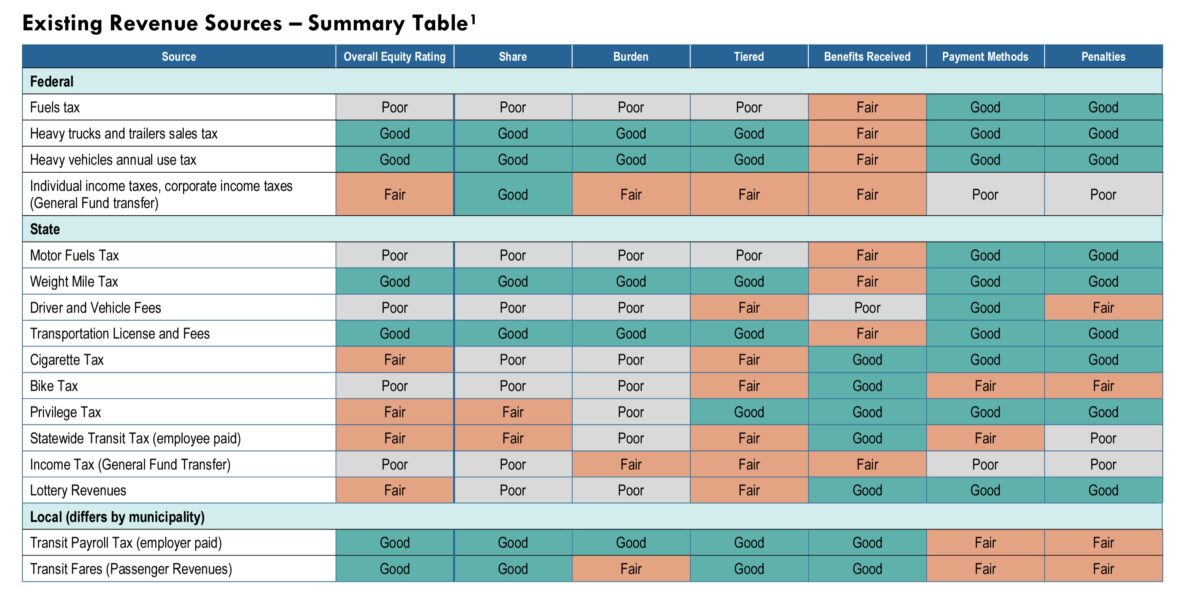

Considering all of this, the researchers came up with six equity assessment measures for revenue sources, and then gave a rating to each source. Below are the metrics they used to inform the rankings:

— Share: Do lower-income households pay a higher share of their income?

— Burden: Does the source provide subsidies or exemptions to alleviate unfair burdens?

— Tiered: Is the fee or tax graduated based on the value of the item?

— Benefits: Are low-income households and people of color directly benefiting?

— Payment: Are unbanked or underbanked individuals unfairly penalized?

— Penalties: Do unpaid fines, fees, or taxes trigger penalties and legal repercussions?

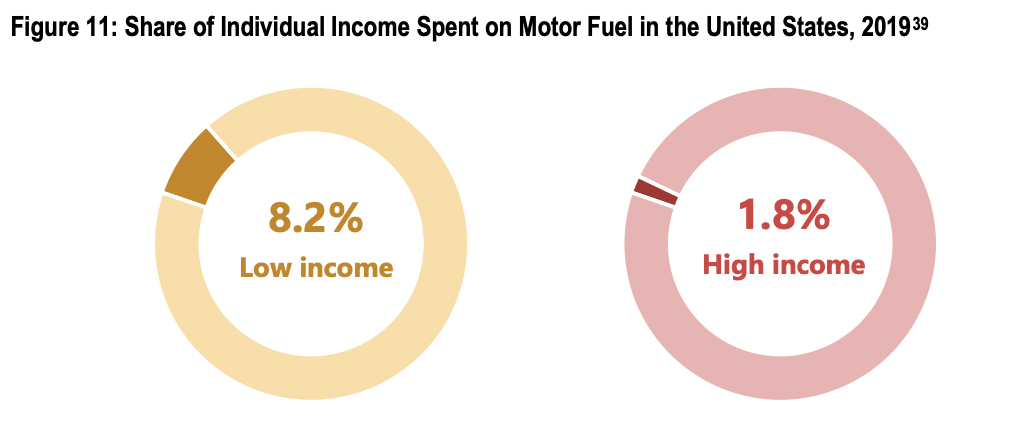

They used this list to analyze some current revenue streams. One of the funding sources they looked at was the gas tax, which the report says is one that has “compounding and regressive impacts on lower-income communities” because it hits harder on poorer people who are more likely to drive cars with low fuel efficiency.

The report also analyzes other income streams like transportation system development charges and property taxes, which they say are also regressive.

But there are ways to combat this. First, the report states possible revenue streams that can be applied with more discretion, like road use fees, which have “greater flexibility and potential for targeted exemptions that could mitigate outsized burden.”

Other suggestions in the report include: restructuring fines so they don’t impact credit scores or employment eligibility, prorating payments based on income, advocating for more lenient fare enforcement policies, adjusting the gas tax according to inflation, and financial assistance programs like the City of Portland’s Transportation Wallet.

Where the money goes matters

In the long-term, transportation agencies should want to use the income they receive to create a more sustainable system where people can get around without the expense of a car. This means investing in alternative transportation options in the communities that need them the most, which would mitigate some of the inequities created in revenue collection.

The report says the best way to do this is to spend money raised on projects that boost safety, transit, and biking and walking infrastructure. Other recommendations include anti-displacement strategies, and cash incentives to encourage lower-income households to reduce their carbon footprint through the purchase of things like EVs, solar panels, or transit passes.

This report is an excellent resource for anyone who wants to understand not just how transportation funding works, but how to make it work better for the people who need it most. Check out a PDF of the report here, and stay tuned for more updates on the RTP process.

Thanks for reading.

BikePortland has served this community with independent community journalism since 2005. We rely on subscriptions from readers like you to survive. Your financial support is vital in keeping this valuable resource alive and well.

Please subscribe today to strengthen and expand our work.

As this report notes, gas taxes are among the most regressive taxes in Oregon. I also remember very well how many active transportation enthusiasts in the bikeportland comments section fawned over Portland’s gas tax increase while dismissing their unequal impact on lower income people.

Gas taxes should be much higher to reflect the external costs of driving.

Cigarette taxes are highly regressive, as are marijuana taxes and alcohol taxes, and vehicle registration fees, and museum admissions, and apartment rents, and bicycle tire repair charges.

Overall, life is pretty regressive.

Even if you don’t care about burdening poor people with grossly disproportionate taxation, the external costs of driving are increasingly not captured by gas taxes.

I care about burdening polluters with the cost of their pollution; the tax should be based on the damage done. That is proportionate taxation.

I assume the bold part of your comment refers to electric cars, and I agree that gas taxes undertax these vehicles. I would prefer a carbon tax to a gas tax, but an increased gas tax would be (much) better than nothing.

My ideal solution would be a steep carbon tax that is then redistributed on a per capita basis. Anyone who uses less carbon than average would get a check. Since you frequently assert that rich people pollute more, this would benefit those earning less, though the real purpose would be to reward those polluting less.

And, as Adam notes below, reducing pollution would benefit poorer people more (the core thesis of environmental justice), so any of these arrangements would be disproportionately beneficial to people with less.

A tax is a thing we decide to put on people. It’s not a naturally occurring phenomenon. So it doesn’t have to be regressive despite your naive analysis of the situation.

Soren is right. Gas taxes are regressive and are the wrong way to raise revenue or deal with climate change.

I don’t want to use a carbon tax to raise revenue, but to reduce emissions. I wrote above that I would support returning the bulk of the proceeds to the people in the form of a cash payment. Those who pollute less would benefit more, so it could be a progressive arrangement.

For me, the goal of emissions reduction is so important that it overrides most other considerations. I realize that many don’t share my sense of urgency on the matter, and seek to burden the already difficult problem with unrelated social goals, an effort I see as tantamount to blackmail.

LOL at the belief that small increases in gas taxes do much to decrease the emissions of the middle and upper classes — you know, the people who do the vast, vast majority of polluting.

I would happily support large increases in gas taxes – say something in $5-$10 range — because this would be functionally equivalent to a mandate and would necessitate a social backstop for the low-income workers that are essential to our economy..

If this were true, then you would support the political revolution/transformation necessary for rapid imposition of decarbonization mandates. The incremental tweaking of taxes favored by liberals/neoliberals is pathetically insufficient for the sharp drop in emissions needed to stay within 2 C.

Soren out here starting The Revolution from the Bike Portland comments section. 😉

And Will in the Bike Portland comments mocking the idea that the only moral response to the climate crisis is transformative change.

Who said anything about “small”? $5 or more sounds quite reasonable, though I would do it gradually, predictably, and regularly, rather than suddenly. Of course, I want something that works rather than something theatrical.

My OP referred to Portland’s 10 cent gas tax which I hope you will agree is a small gas tax in city with a median household income of $84,000 (2021). Novick proposed this tax only after buckling to PBA lobbying. And he did this despite the fact that polling showed overwhelming support for a progressive income tax that spared low income people entirely.

Just about every urbanist in PDX supported Novick’s move away from a progressive income tax towards an immoral regressive tax. This history epitomizes the gaping chasm of political disagreement I have with urbanists/YIMBYs.

“10c”

A $5 gas tax could never work at the city, county, or even state level, so if you are talking about a revenue raising tax at the city level, 10c is probably all you can do before introducing undesirable side effects.

When will progressives/liberals/moderates realize that tiny piecemeal reform is just another manifestation of climate crisis denial?

Imagine the bureaucracy needed to make that “equitable”. only people earning above $125k would have to pay it.

Really? Please show us the data that proves middle and upper class people do the vast majority of polluting.

IMO, CORPORATIONS do the vast majority of polluting and those corporations’ products are used by people across the socio-economic spectrum.

https://www.lse.ac.uk/granthaminstitute/publication/income-inequality-and-carbon-consumption-evidence-from-environmental-engel-curves/

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0160412019315752?via%3Dihub

The upper 10% includes no or very few true ‘middle class’ households.

The median household income in Portland is $84,000 (2021). Please note the size of the yellow-orange bars in the $70,000+ income range versus those of lower-income Portland households.

It’s amazing that someone could be this obtuse about the role of economic disparities in perpetuating CO2e pollution.

The middle class has much more in common with the lower classes than with the upper classes, which is why the upper class spends inordinate amounts of time and money fomenting dissention between the lower and middle classes; they know that if the lower and middle classes – which together make up the vast majority of the population – ever united against them, their power, wealth and lifestyles would be toast.

And I’ll bet you anything that if the ‘$150,000 and more’ bar in your graph were to be further parsed, the true discrepancies between the middle and upper classes would become abundantly clear and the relatively small differences between the lower and middle classes would look a lot less egregious.

Your chart is completely disingenuous in this way, since $150K is hardly a wealthy family’s income, in this day and age it is solidly middle class. There is a reason your source isn’t parsing and publishing the rest of the higher income bars, and you’ve fallen into their trap.

Let’s see some further upper income divisions in that chart, like $150K to $250K, $250K to $1M, $1M to $25M, $25M to $250M, $250M to $1B, and greater than $1B. That’s gonna be the part of the chart where all the action is and they aren’t even showing it.

And when you are talking about the ultra wealthy, ‘household carbon footprint’ doesn’t even come close to capturing their total actual ‘carbon footprint’, since the carbon footprint of people at those income levels extends way beyond some arbitrarily defined household boundaries.

Tell me about these “unrelated social goals.”

The advantage of spending all the available money conducting study after study is that one will not be accused of implementing something that is inequitable, racist, sexist, or damaging to some marginalized segment of society. On the other hand, we don’t see any unsafe conditions improved either.

It’s worth underscoring how difficult it is to capture all of the tradeoff’s that impact equity in a simple matrix like this. One could argue that because pollution and climate change disproportionately impact low income people that disincentivizing the consumption of fossil fuels with taxes is in fact an equitable policy. Similarly one could argue that a flat payroll tax is inequitable because employers tend to pass on tax burdens in the form of lower wages and because taxes comprise a bigger share of a low wage employee’s total costs to employers it will hurt wage growth most in the lowest tier of earners. There are of course complicating factors in both of these examples but it should give you pause before making policy decisions on the basis of this type of very crude analysis.

And yet the Metro Council signed off on spending multiple billions of dollars to expand highways help Vancouver commuters…. almost as if they don’t read their own reports.

Bike cars, and level boarding. Metro could fund bike cars on public transit to accomodate a wide variety of devices for all the people they have effectively barred from public transportation & mutimodal options. For all their talk of equity, they almost never mention disabled people.

Equity has recently entered the government lexicon as the newest buzz word, but it remains to be seen whether it will amount to anything more than a buzz word, solely used to greenwash new projects in a different way.