Cars are so ubiquitous in the United States it’s hard for some people to believe it’s possible to live without one. But in order to meet a host of urgent local, regional and national environmental and public health goals, we must drastically cut down on vehicle miles traveled (VMT). In short: people need to drive less.

Developing a system where people without cars can have the same kinds of experiences in the outdoors as people who do is crucial.

Luckily, while cars are ever-present in American society, not everyone actually owns a car. Transportation engineer Randy McCourt presented data Wednesday at the Oregon Active Transportation Summit (hosted by The Street Trust) that revealed more about who is carfree, how they do it and what we can do to encourage no-car living more broadly.

There are more than 280 million vehicles in the U.S., but that doesn’t mean that 280 million people own cars: many households own more than one. Census data shows that about 9% of American households don’t have cars, while almost a quarter of households own three or more. The majority of households own one or two.

You can glean a lot more from this data by focusing on which places in the U.S. are home to the most and fewest zero auto ownership households. In Washington, D.C., 35% of households don’t have cars. In New York State, it’s 30% – but this number is higher statewide because of New York City, where more than half of households don’t have cars.

On the other end of the spectrum, you can find staggering auto ownership rates in places like Raleigh, North Carolina and Riverside, California, where roughly 96% of households own cars. Here in Portland, we have slightly more auto ownership than the rest of the country: 92.2% of households have auto access compared to 91.6% nationally.

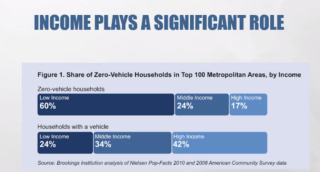

So what are the factors leading people toward or away from zero auto ownership? One important element is income. We are currently seeing initiatives underway across the country to provide financial resources for people burdened with the cost of higher gas prices. Some of these proposals also include some money for public transit, but usually presented as an afterthought.

But when you look at the data, it’s clear that low-income households are, in fact, much less likely to own a car. The chart at right shows that on average across the country, 60% of zero car households are low-income.

It follows that places with high walk-bike-transit scores have higher numbers of zero auto ownership households. While it’s good to point out this relationship, it’s not particularly groundbreaking: a key component of active transportation advocacy is that investing in alternate transportation encourages people to drive cars less.

Advertisement

“I’ve actually been considering buying a car now that I’ve been working remotely full-time to just get out of town more.”

— Alison Percifield

McCourt also brought up the commuting trends developed during the pandemic, saying he thinks working virtually has the potential to go into the future and mitigate the need for mass car ownership. However, a member of the panel discussion, Alison Percifield, spoke up to say she is actually considering buying a car for the first time in almost 15 years right now, even though she works from home and the price of cars is so expensive.

“I’ve actually been considering buying a car now that I’ve been working remotely full-time to just get out of town more. Going back to work isn’t really a consideration in buying a car,” Percifield said.

Portland Bureau of Transportation planner Zef Wagner echoed Percifield’s perspective, saying the feeling of stuck at home during the pandemic motivated him to buy a car when he previously didn’t have one. Wagner also brought up another interesting point: for people who used to commute to work via transit or bike, getting out of the habit because their jobs went virtual might make them weary of it.

“I worry that the effect on people’s comfort with transit will linger for quite a while,” Wagner said.

Personally, I’m troubled by the association people have between car-ownership and freedom. I understand it, because it has been ingrained in Americans via incessant car ads and infrastructure built for drivers. But I feel far freer without the burdens of making car payments, buying gas and insurance and shelling out for car maintenance – not to mention the hassle of finding a place to park – than I would just by knowing I could hop in my car and head to the coast whenever I wanted to. We need to create systems where people can see all the beautiful scenery that we have nearby without having to drive to get there.

McCourt said developing a system where people without cars can have the same kinds of experiences in the outdoors as people who do is crucial.

“We want to think this through to those pieces of the puzzle so that we can create the environment where if you were at zero auto ownership, you could feel the experience of freedom, you wouldn’t feel trapped,” he said.

There’s a lot to consider when it comes to zero auto ownership, and while we didn’t find the key to it in this discussion, I appreciated hearing what people had to say. The benefits of zero auto ownership are substantial enough for the environment, congestion reduction and health that it’s worth spending more time to analyze how to implement it on a larger scale, and find out which less-quantifiable factors are leading people to own cars even though they may not need them.

CORRECTION, 4/29 at 7:05 am: This post was published with an incorrect interpretation of the chart about carfree households. The author initially claimed 60% of low-income households don’t own a car, when in fact the chart shows that 60% of households without a car are low-income. We regret the error and any confusion it caused.

Thanks for reading.

BikePortland has served this community with independent community journalism since 2005. We rely on subscriptions from readers like you to survive. Your financial support is vital in keeping this valuable resource alive and well.

Please subscribe today to strengthen and expand our work.

“We need to create systems where people can see all the beautiful scenery that we have nearby without having to drive to get there.”

Exactly this, there is no easy way to get to Mt Hood and to most of the coast without either several transfers or taking much longer than needed.

And Mt. Hood and the coast are just 2 destinations out of hundreds that people go to for recreation. It is not possible to have a public transportation system that allows people to get to all the remote places they go to hike, fish, ride horses and motorcycles/ATVs, hunt, camp, etc. There isn’t enough money on earth to build a public transportation system that would cover it all, much less maintain and operate it.

Quote from the article: “….a key component of active transportation advocacy is that investing in alternate transportation encourages people to drive cars less.”

MAX, buses, and bike paths encourage a few people to not drive, but at a cost that is many times the cost of them owning cars. It just doesn’t seem like it because the cost is spread out over all the tax payers.

Fact is, people want to go where and when they want. Cars allow that freedom. Car commercials have nothing to do with it. It’s just practical.

The solution? Stop trying to force your values down the throats of Americans. Let the market do it. Energy will get more expensive, and that will change their behavior. Metro/MAX/buses and all the arm waving and screaming and yelling about the evil cars will do nothing but make people want to drive cars even more. And they probably will drive more – but soon it will be mostly electric – that’s what you want, right? It’s a comin’.

Top down solutions don’t work. Let the market allocate resources in the most efficient way. It will.

I’m glad to hear that you support the elimination of single-family zoning and parking minimums, and the elimination of federal spending for highways. Let the market decide!

I’d say sure, get rid of single-family zoning. Let the land owners decide. They can band together and make an HOA if they want to mandate single family. Note to the wise: NEVER buy in an HOA. Parking minimums? Let the home owner or developer decide. You don’t like how they built it? Then don’t buy it. Federal spending on highways? Sure, eliminate it, cut federal taxes, and let the states collect and spend it – would probably get a lot better bang for the buck. I’ll bet the waste in the Fed system would make both Ds and Rs puke.

People who have continued to commute to work by bike during the pandemic have considered this point because formerly busy bike lanes are empty during commute hours.

Car ownership may go away when equivalent transportation services are available via another mechanism. The only possibility I see on the horizon is robotic taxis.

TriMet operates on a 19th century service model, and provides service that is in no way comparable to the benefits of car ownership. Bikes are only a good substitute for a subset of trips and a subset of people.

People are willing to pay to own a car because it really does make a lot of things easier. I say this as a car owner who drives perhaps 5-10 times a year.

Driving a car is more comfortable and faster because of policy decisions, not because of some intrinsic truth. Our entire transportation system is set up to benefit private motor vehicles, so of course people prefer to drive. When a bus ride takes twice as long and is just as prone to traffic, of course people don’t like taking it. When the MAX comes every 15 minutes at best, mostly only at “peak hours”, of course people won’t use it as much. They just don’t provide competitive service.

Bikes (and e-bikes) can be a hard sell because of land use and transportation policies lead to biking being uncomfortable or dangerous. You can see this even in Portland – compare to literal distance of a bike trip and a car trip. The bike trip is almost always longer. This causes people to bike less.

The solution to this isn’t to continue on 20th century pro-car transportation and land use policies, it’s to prioritize land use and transportation that makes living in a city great.

Intrinsic truth might be getting a bit philosophical, but a scheduled service on a fixed route in a shared space will never replace a private, point-to-point on-demand service in the general case. If you happen to be going where and when the bus is going, and the buses are clean and well managed, then yes, it’s great (I took transit this weekend, for example; not great, but it worked well enough for someone committed to minimizing their footprint). But there are inherent deficiencies with the TriMet model that are difficult to overcome, especially if you are constrained by emissions and budget.

Our current landuse policies are pretty much baked in at this point, so any solutions need to accommodate that reality. Yes, the built environment can and will change over time, but in 50 years, the physical layout of Portland will look much the same as it does today, just as it looks pretty much the same today as it did 50 years ago.

Scheduled service on fixed routes dominate the transportation in basically every large metro in the world. London, Paris, New York, Hong Kong, Singapore, Toyko, Mexico City, Shanghai etc. They dominate because rapid transit is simply much more economically (and geometrically) efficient than private vehicle ownership.

If our land use policies are bad, we should change them. It doesn’t matter if they are “baked in”, if they are bad they should be changed.

And Portland looks radically different now than it did 50 years ago. The Fremont bridge is less than 50 years old. The MAX is less than 50 years old. The population has doubled.

The cities you named have two attributes in common that Portland does not share: scale and density.

Sure, change the policies, but when the built environment is already built, the cost of implementing them becomes impossible over anything but the longest term. We’re not going to raze East Portland and rebuild it after the streetcar model, then raze the suburbs and move everyone into the inner city, which we’ll need to raze and rebuild to accommodate.

It’s far more efficient to build a new city somewhere else then try to build one where a different one already exists.

And no, Portland does not look “radically different” than it did in 1972. A new bridge or two, a new max system, yes, but the fundamental landuse patterns that were there then are there now, even if expanded upon somewhat.

Once something is built, it’s awfully hard to change.

I’m sorry, but your objections are patently ridiculous. It is absolutely not the case that it’s more efficient to build a new city somewhere else, on almost any metric. You mean to tell me you honestly think it’s more efficient to build new electrical, sewage, and transportation systems in exurbs than it is to densify places where those already exist? There’s a plethora of data that suggests the opposite.

Especially in a place like Portland where the ingredients are already there to support much greater population and population density–especially the MAX, which could provide service for a magnitude more people than it does now–it’s always going to be more efficient to rebalance our legal system to stop privileging existing SFH owners and build a much more dense and urban environment within the infrastructure we already have.

Whole areas of the city probably should be razed and rebuilt at much higher density, but going block by block near MAX stations and in areas served by the bus (along with very inexpensive changes like bus lanes and priority signaling) and mandating new construction (those there currently can accept new housing in place or leave) is not actually that difficult. All that’s lacking is the sociolpolitical courage to realize things are going continue to fall apart otherwise.

I do not believe the areas like East Portland can be remade in a manner that would make transit as attractive as point-to-point modes of transport without fundamentally rebuilding everything, including the street network, and therefore the sewers and electrical grid as well. That hasn’t happened anywhere else in the US, and it isn’t going to happen here.

Nibbling away at the edges by densifying along Max lines may make sense, but it just doesn’t address the problem on the scale needed to make fixed route fixed schedule transportation attractive compared to driving.

There is also the fundamental problem that most people do not want to live in dense apartment buildings, at least not once they get to the family stage of life. So not only would razing and reconstructing huge sections of the city be enormously expensive, it would also be producing something that most people do not want.

Patently ridiculous as my objections may seem, they are firmly anchored in reality. I believe we will find solutions, but I think they will require new thinking, not doubling down on old ideas.

I am optimistic. I believe new technologies will allow us to reimagine the city in ways that let us make much better use of our built environment than we currently do. We already see glimmers of that with work-from-home and the rapid cultural shifts that have accompanied it.

If your life no longer revolves around going downtown, why would you value living on a Max line that doesn’t take you anywhere else?

Most people don’t want to live in dense apartment buildings during the “family stage of life” because the American paradigm for family housing is “I have a (1) child, so I need 2000 sqft of space” (not sustainable on its own, in anycase), and the American paradigm for building apartments is 2 bedrooms, unless it’s a penthouse, without a pocket park that serves as a neighborhood gathering spot with small commercial developments nearby and a place for kids to play under the watchful eyes of familiar faces.

There is nothing about the American model of urban development that is socioeconomically or environmentally sustainable, not a thing. These things will have to change; if we don’t do it, the world will do it for us, and it won’t be gentle if it comes to that.

There we go with the optimism about “new technologies”. Why should any new technology save us from poorly using it to solve our issues if we can’t even use our current technologies to abate issues they are already perfectly able to solve? What “new technology” is going to save us? Remote work? Robotaxis? What evidence do we have that these are here to stay permanently or ever going to be here at all, respectively?

And the economics of agglomeration are always going to favor central business districts, as long as picking up the sort of social cues you can only discern from actual physical proximity to another human being remains relevant, not to mention that culture diffuses far more efficiently in dense places. I know we’re an adaptable species, but I don’t think we’re going to outgrow several tens of thousands of millenia of evolution in a few decades’ time.

I’ve noticed that many prominent YIMBY/WIMBY organizers are homeowners who lobby for zoning changes that favor the construction of more 2000 square foot single unit houses (e.g. RIP2 anti-renter lot subdivision deregulation).

I find it interesting, that what maybe 5%, or 10% if I’m being generous, of the population think they are going to force the other 90-95% to live the way they want them to.

How are you going to pursuade the media and ad agencies to quit portraying the “american dream” as a 2K’ house and a white picket fence?

Forcing people is going to meet resistance.

Try persuasion. It won’t happen over night but it might be embraced more whole heartedly. Ad-campaigns that show a better “american dream” might gain some traction if done right.

Blame the “paradigm” if you will, or tell me how people should be different, but that doesn’t change the reality of the housing types people prefer.

Because it always has. True, I have no proof that remote work will become a permanent fixture (nor you that it won’t), but given its advantages for employer and employee alike, it’s hard to see it disappearing. Robotaxis may seem a bit more speculative, but the rate of computational and technical advance convinces me they’re coming. I will assert (and you may agree) they would represent the first fundamentally transformative force since the adoption of cars, and would be equally significant.

Maybe for some things, but envisioning a city with many smaller neighborhood hubs that offer dining and entertainment and business services is not much of a stretch, and if people are spending more time at home, it is easy to see these centers growing and becoming more significant.

Two years ago I traveled downtown daily. Now I might go 10 times per year, if that, and I can state with near certainty that for me, the shift is permanent (like my decision 20 years ago to never take another job that required commuting by car). I’m hardly alone. I don’t need transit to take me downtown. And, given TriMet’s collapsed ridership, many, many others don’t either.

Agreed! Our family lives in the Sellwood neighborhood, and that is a pretty good model for the “complete 20-minute neighborhood” — with a wonderful mix of local businesses offering a full gamut of goods & services including access to the multi-use Springwater Corridor & Milwaukie/Trolley Trail bicycle paths; multiple bus lines & multiple light rail transit stations; natural foods stores, restaurants, cafes, bistros, bakeries & food carts; retail clothing stores; barbershops & salons; gyms, fitness centers, personal trainers, Yoga & Pilates studios; Martial Arts, Dance and Music instruction; medical services of every stripe; childcare; antiques, vintage, and used goods vendors; bicycle stores; pet stores; several book stores; as well as “experiences” (including the library; trackers; makers & instructors; proximity to several nice parks, the waterfront & many festivals; The Sellwood Community Center & the Sellwood Pool; Oaks Bottom Wildlife refuge & more!) that are conveniently available within a short walk — with adjacent additional cultural & commerce hubs of Westmoreland, Woodstock, and Milwaukie a short bike ride away (with 3 hardware stores; movie theaters & arcade; more parks & waterfront, etc.! The historic SFH model is also giving way (though not without considerable resistance) to higher-density development. For most of the nearly decade-and-a-half that we have lived here, our family of six has been car-free [due to recent unforeseen circumstances, including aging – as well as a serious injury and subsequent long period of rehabilitation – we finally caved and purchased a pre-owned 2013 Nissan Leaf EV for wintery cross-town errands].

Damn fine comment, luv the forward momentum of that long list. But did you leave off Oaks park and roller skating rink? Is that still there?

Whole areas of Portland are being razed and rebuilt as 6 story (or more) condos and apartments. What’s going away are single story light industrial and commercial districts. In many cases the jobs those areas represent are moving to suburban areas. We have zoning pressure to create ground level stores and restaurants but really, how many boutiques do you need?

Which “whole areas”? A narrow strip of development along Division (for example) that was more building on parking lots and vacant land than actual redevelopment caters to a narrow demographic and only seems transformative if you don’t walk a block north or south of the corridor.

The Pearl or South Waterfront, maybe, but in both cases the underlying land underutilized (or even unutilized), and was not filled with people and their homes and their lives, and both had a geographic logic that’s hard to reproduce (and neither are places I would want to live permanently).

NW Portland goes well beyond the Pearl. There was formerly a concentration of light industrial buildings (and one steel plant) between approximately Powells Bookstore and Montgomery Park. Of course there were, and are, still lots of residential houses and some offices mixed into that area.

The pricing pressure of multi-story residential development has pushed out businesses that rent and offers such a bonus to owners that it’s hard to resist the tendency to move away. You can still find the occasional bearing supplier or car repair shop but the printing plants are gone and the metal shops are gone.

It’s not just the Northwest, the same thing is operating on the Central Eastside, just not quite as thoroughly. It doesn’t have the same name recognition or the pattern of new transplants moving to Portland and finding a place in NW before discovering other parts of town.

Of course it’s not merely land prices at work here. The challenge of shipping in materials and the conflict between noisy operations and adjacent condo dwellers can’t be ignored. The pattern of change is self-catalyzing.

According to the Jacobsian market fundamentalism that dominates planning in PDX there can never be enough doggie daycares, boutiques, canna dispensaries, brewpups, brunch spots, and coffee shops.

That can only be built on a miniscule number of treeless microscopic plots adjacent to toxic polluted traffic sewers (while homeowners continue to swim in the capital gains of verdant and oh-so-exclusionary neighborhoods).

Also, if this were actually true I would be less critical of the “trojan horse” incrementalism of YIMBYs (e.g. their claims they they care about renters while strenuously advocating for lot splits that disincentivize rental housing).

If anyone is interested:

https://blog.trimet.org/2021/11/02/how-to-travel-oregon-without-a-car/

yes! Thanks for sharing that ChadwickF. I actually have a draft post sitting here that was just a republish of that exact post.

Love the analysis of income and car ownership… America’s car addiction feels like as much a cultural issue as an infrastructure/planning/development problem.

People want to get in the car, go do an errand, come back and park. All while sitting in their comfortable climate-controlled car on that cushy foam seat. It’s practical. It works great. Most have zero interest in biking, taking a bus or MAX. But electric vehicles are coming, are here for a few already, and that’s part of the solution to CO2 or so they claim. We’re making progress slowly. For those who want to bike, or take pubic transportation, it’s there for you.

That chart shows that 60% of zero-vehicle households are low-income, not that 60% of low-income households have no vehicle.

CORRECTION, 4/29 at 7:05 am: This post was published with an incorrect interpretation of the chart about carfree households. The author initially claimed 60% of low-income households don’t own a car, when in fact the chart shows that 60% of households without a car are low-income. We regret the error and any confusion it caused.

Thanks For Sharing Such beautiful information with us.

Funny thing is, I found this article because I was doing research for an essay on why we need rail transit to Mt. Hood, where I was mostly going to write about car ownership and regional rail for trips to the mountains/lakes/coast.

you cannot get rid of individual car ownership until you change the way poeple make a living. This will never be through big government since this is just corrupt because people are fundamentally corrupt. So you can only rely on yourself to make a living. And your individual car to make it happen. Car free is and will only be a dream until life fundamentally changes for everyone.