(Source: Streets 2035/PBOT)

If you’ve ever wondered who-gets-what-and-why on streets and sidewalks, you might want to tune into the Portland Bicycle Advisory Committee meeting Tuesday night (10/12) where managers of the city’s Streets 2035 and Pedestrian Design Guide projects will be presenting.

We know it sounds dry and wonky, but there’s reason to pay attention. Here’s why:

At their heart, Streets 2035 and the Pedestrian Design Guide update are silo-busters. Each brings together the different bureaus, or groups within bureaus, to weigh-in on how they use the right-of-way (ROW): stormwater, sewer, utilities, transportation, parking, trees, bike racks, restaurant seating.

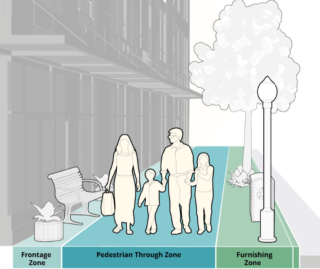

The two projects are tandem efforts by the Portland Bureau of Transportation (PBOT) to address the conflicts that can arise from a common situation: when we have competing demands on constrained rights-of-way. Streets 2035 is the more fundamental (and potentially game-changing) project. Its scope is the entire right-of-way (as seen in above graphic), and the effort is about a year away from completion. The update to the 1998 Pedestrian Design Guide (PDG) focuses on the part of the ROW designated for pedestrians, and that team recently released its draft Guide for public comment.

Advertisement

The PDG begins by pointing out that the responsibility for the construction and repair of sidewalks falls on the adjacent property owner. Thus the predicted influx of 600,000 new Portlanders by 2040, and the adaptation the Residential Infill Project to address our missing middle housing, provide an opportunity to build a more complete active transportation network. Frontage improvement requirements are triggered by development or redevelopment of property. That means Accessory Dwelling Units (ADUs), a converted garage or new second-story, may require improvements to the ROW in front of the property. If the city hopes to meet its global warming and ride share goals, it must capture and strategically direct those development dollars.

The PDG is mainly an internal document for city staff and, as such, the process differed from the usual drill of advisory committees, 18-months of meetings, draft report, City Council vote. Instead, the effort was informed by two preliminary studies: focus groups conducted with the PBOT work groups that use the guide the most, and interviews with peer cities to learn best practices.

The focus group summaries in particular pull back a curtain to reveal the challenges staffers face when allocating space. Feedback included a request for direction on how to implement the transportation hierarchy, a “process for decision-making when trade-offs need to be made,” and mention of the challenges of working with “internal partners,” i.e. other bureaus, and the placement of their infrastructure (e.g. water pipes and trees).

Common themes that emerged from the focus groups were a need for context-sensitive solutions, flexibility, and reconciliation with other “(sometimes conflicting) guidance.” The draft PDG appears responsive to these concerns, and in general clarifies the ROW uses and policies which have emerged in the last 20-odd years. It includes a big section on “Alternative Pedestrian Walkways” which can be used at the discretion of staff when a full sidewalk can not be constructed. BikePortland reported one alternative walkway in the Cully neighborhood last May.

(Photos: Jonathan Maus/BikePortland)

These situations requiring alternatives often arise in parts of the city that lack standard stormwater infrastructure, and thus the drains required for cement sidewalks (see the “Western” and “Industrial & River” areas of graphic above right). The total lack of pedestrian or bicycle facilities can make people developing property reluctant to pay their portion of something that doesn’t exist at all. Dealing with that problem, referred to as “proportionality”, was one of queries put to peer cities. The Denver, Colorado review put it best:

This ask, and its relationship to proportionality, is a consistent point of contention between the City Attorney, permitting staff, and developers even though … development code clearly states that the property owner must provide the needed ROW to meet the transportation standards.

Austin, Texas seems to be a model city in its proactive handling of proportionality and formal documentation justifying frontage improvements. This seems like the strategy the PDG would like to pursue:

Portland staff have discussed with the City Attorney how and what sort of proportionality documentation would be needed to help get the needed space from developers. While the City Attorney expressed that additional documentation would be helpful, there was no formal commitment that it would be enforceable. This enforcing of an ask for and required giving of additional space would need to be supported by City and PBOT leadership, which will be a longer process than the PDG Sidewalk Corridor section update entails. It is recommended that this conversation continues amongst PBOT, Streets 2035, and legal staff as they look to consistently ask for and/or obtain the space they need for a ROW that meets the Portland’s visionary goals.

Will the city continue to allow increased density in areas where residents cannot safely step off their property? Where go-by-car is the only means of transportation? The answer should be “no”, but that will require the support and engagement of the City Attorney’s office and the leadership of PBOT and the City.

— Lisa Caballero, lisacaballero853@gmail.com

— Get our headlines delivered to your inbox.

— Support this independent community media outlet with a one-time contribution or monthly subscription.

Thanks for reading.

BikePortland has served this community with independent community journalism since 2005. We rely on subscriptions from readers like you to survive. Your financial support is vital in keeping this valuable resource alive and well.

Please subscribe today to strengthen and expand our work.

This has been a problem ever since the City decided to make sidewalks a private responsibility. A complete pedestrian grid is a public good, but we expect the entire cost of it to be carried by private individuals working on their own schedules. Broken pavement on the sidewalk? Nothing to be done until the property owner decides to make a contribution to the public realm. Important sidewalk segment missing? Wait around for enough decades, and maybe someday the owner will redevelop the land and add a sidewalk.

The City really needs to create a public source of funding for sidewalks/complete streets and get to work building them, instead of waiting for homeowners and businesses to voluntarily pick up the tab.

I hope more BP readers take a look at this more ‘wonky’ stuff when it comes to our attention. The Pedestrian Design Guide and the Protected Bike Lane Guide are VERY influential documents on how the City builds the ROW and how we end up using it.

I’m still dismayed that the City puts out all of these guides and plans with the same well-intended goals, but as soon as the shovels hit the dirt, bike lanes and sidewalk corridors end up suffering at the hands of ‘value-engineering’ for vehicle-serving enhancements.

Sounds like a wish list item for SW Portland. There are five other quadrants and absolutely nobody is building large multi family projects there without that basic infrastructure, even where it is generally deficient.

The Street2035 graphic divides the city into five different areas based on several criteria. In the River/Industrial and Western regions stormwater drains into streams, which means that expensive catch basins have to be built to treat the water if you want to build sidewalks. That’s the infrastructure that is lacking. I’ve added a “Related Link” that explains about the basins (“Long advocacy slog …”)

Don’t confuse stormwater conveyance with stormwater treatment. The City appears to be making some headway in this department.

On its face, The City’s new stormwater management manual allows new sidewalks and pedestrian connections to be constructed without stormwater treatment.

And yes, new sidewalks will likely require new stormwater infrastructure, including new catch basins and pipes, which can add a significant cost to a project. But if you put in a new curb and sidewalk and stripe a new bike lane, you going to want a place for water to go that doesn’t pool up in the bike lane or in front of the ADA ramp.

Stormwater treatment is an additional cost to the catch basins and pipes infrastructure, which usually requires additional real estate to implement.

Lake Oswego was considering making the Lake Grove project on Boones Ferry Road have the stormwater sloped to the middle of the new “parkway” to make it easier to give water to the vegetation and that would have been so nice for riding a bike or similar device, but they ended up going against that.

This roadway design approach (“valley” versus “crown”) also minimizes the amount of debris that accumulates in bikes lanes. Not sure if this is a good side benefit or not but it also makes sidewalks higher than the travel lanes.

However if you were to design a whole road network this way you would end up with low points in the center of intersections. I suppose roundabouts could minimize this concern.

These are the stormwater basins the 1-mile long new bike lane and MUP along Cap Hwy require. BES describes them as treatment and detention.

Sorry if I’m not following, but it sounds like if a street doesn’t have sidewalks and is topographically prevented from having them, then you either can’t build density or still have to pay for sidewalks and bake that price into housing.

If you can do it at all, subdividing or adding a dwelling to one of the many R7/10,000 sf lots in SW sounds like a fast way to go broke. What a boon for reinforcing the

FWIW I live in a duplex on an R2.5/4000sf lot, not too different than much of the rest of the east side. We welcome more variety and density on my block, but if this is what I think it is, some parts of the city feel exempt.

Or you can get the density, but simply wave your hand and waive transportation/sidewalk requirements!

“Level of Service Update Project (in progress): PBOT is investigating a move away from measuring impacts from new development in terms of level of automobile service and instead centering impacts that better align with policy outcomes, such as reducing vehicle miles traveled. Transportation demand management programs and strategies could serve as mitigation tools in new development

Transportation System Development Charges (TSDCs): PBOT has instituted a new methodology for assisting the TSDC fees based on person trips for the type of development instead of car trips. Allowing a more accurate reflection of the reality of how trips are made in the city”

Translation:

PBOT is exploring ways to require EVEN LESS of developers, but charging them more.

Pg. 54

https://www.portland.gov/sites/default/files/council-documents/2021/exhibit-a-the-way-to-go-plan-reportv.1.pdf

Champs, it’s not what you think it is. The last block quote in the article makes it clear what PDG is advocating for–and I agree with them. Basically the City Attorney has to have Development Review’s back, and DR needs to give the City goal of connected pedestrian and bicycle networks a higher priority in its approval process. If that doesn’t happen, expect more SW cars on the freeways.

The fact that basic pedestrian transportation infrastructure is mostly privatised in Portland speaks to the disregard this city and its leaders hold for pedestrian-style transportation (both rolling and walking). IMO, all sidewalks and sidewalk ROW should be public property (via eminent domain, if necessary).

The city’s own estimates show that Residential Infill Project does virtually nothing to address missing middle “housing”. In fact, a significant number of neighborhoods are estimated to see a net loss of housing and the few areas that are expected to see a small increase in density are those most at risk for gentrification (and also those with poor pedestrian infrastructure).

Source: https://www.portland.gov/sites/default/files/2020-08/exhibit_b_volume_3_all_appendices_adopted1_1.pdf

And thanks to SB458 (championed by Sightline, P:NW, and other prominent RIP supporters) the vast majority of homes built as a consequences of RIP will likely be $0.7+ million dollar single household homes. Activists who genuinely cared about our ongoing [rental] housing crisis sought a limit on lot subdivision and unit minimums but policy that actual favors rental housing was, as always, not a priority for Portland’s so-called YIMBYs.

“Map 7 shows that through 2035, with the proposed amendments, some areas of Portland see net increases in redevelopment and new housing units, and some areas see net reductions in redevelopment. The reduction in redevelopment alongside increases in new unit production is the result of allowing multiple units within one structure, which absorbs unit demand that otherwise would have occurred in one-for-one redevelopment situations in the baseline Comprehensive Plan scenario. In other words, current regulations result in more houses being demolished and replaced with a single house, while the proposed regulations result in fewer houses being demolished because more units can be produced on the same site.”

So … no comment on the fundamentally anti-multifamily housing and anti-renter bill (SB548) passed by the main backers of RIP?

Also:

I’m a little bemused by this. Isn’t your whole thing that developers shouldn’t be allowed to tear down housing to build new housing? And you are complaining because RIP will slow the rate of demolitions while increasing the housing stock?

RIP slows the demolition rate of bougie single family housing in well off neighborhoods as clearly shown by Map 7 of the City’s own analysis.

My thing is multifamily rental housing and I would be ecstatic to see every single low-occupancy detached home in PDX replaced with lots of green space and clusters of 8-20 story apartment towers.

Right, and based on earlier discussions, you believe that these single-family homes in close in neighborhoods will be turned into multi-family apartments, correct? Wasn’t that your point when you were arguing that redevelopment is bad because reduces the mythical ‘naturally-occurring affordable housing’?

I think you are having trouble parsing my comments because you simply can’t imagine a preference for non-market multifamily housing (e.g. housing as a basic right in urban centers).

I repeatedly asked for this in public testimony (e.g. FAR-based zoning for residential areas with large bonuses for non-profit housing and most importantly unit minimums). As I stated above my ideal policy would be to demolish low occupancy owned homes in the urban core (including duplex condos) and build huge, massive, ugly subsidized apartment towers.

Unfortunately, RIP and its associated anti-renter legislation have created a scenario where little new housing will be created. And of the small amount of new housing, most will likely be single [household] occupancy homes (see SB458) concentrated in areas with the least built infrastructure and the greatest risk of displacement (see Map 7 above). Also please note the negative numbers (decrease in density) in bougie inner Portland neighborhoods (Map 7).

I live in a “naturally affordable” 12 unit cluster of plexes. I’m fiercely opposed to the replacement of affordable multifamily housing with single occupancy homes everywhere in Portland. We have far too little affordable rental housing and far too much absurdly expensive low-occupancy housing, ATMO.

“The private market cannot provide adequate housing for poor and working people [and the lower middle class], the situation is permanent.”

— Catherine Bauer

https://www.lamag.com/citythinkblog/who-are-the-phimbys/

” get the needed space from developers” — or we could just take it from car drivers. Ultimately they have the bulk of the space in our city and that is where the extra space needs to come from for real improvements. Spreading buildings out by taking land from property owners is not the only way to get better infrastructure

Great comment, Allan, but that’s another article, one I hope to get to this week.

This is a major issue. Sidewalks should be universal and the responsibility of the city, not landowners. Picture the pushback if the same policy were applied to roads. Stop treating sidewalks as less essential infrastructure.