Lower income, Black, indigenous, and people of color are overrepresented in pedestrian crashes, and the State of Oregon has now taken a deep dive into finding out why.

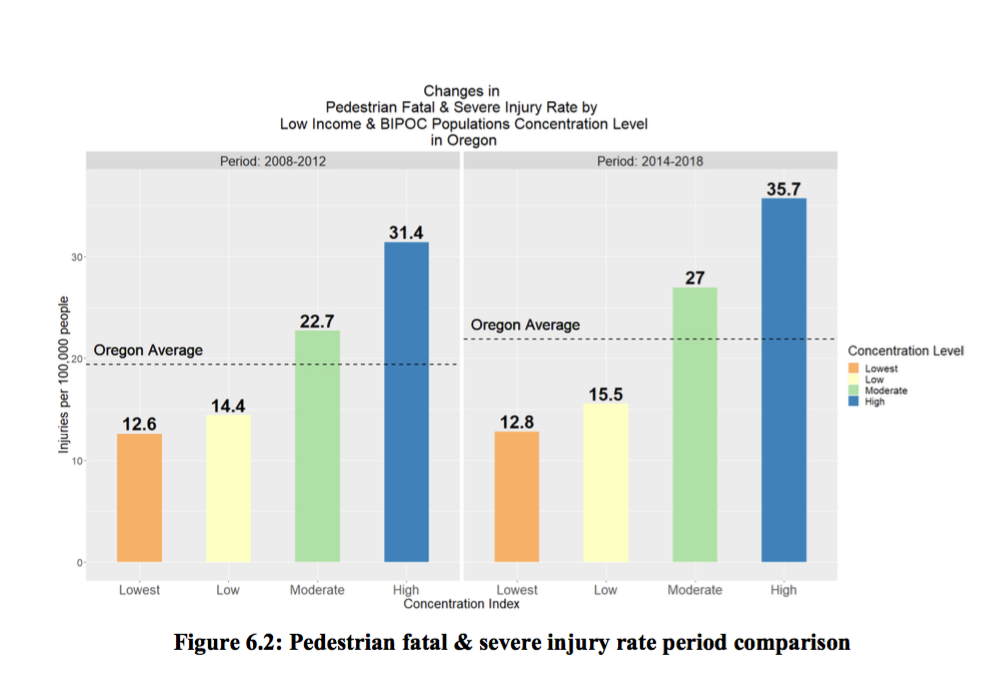

Understanding Pedestrian Injuries and Social Equity (PDF) is an in-depth analysis just released by the Oregon Department of Transportation that examines the relationship between income, race, education, age, disability, employment, land use, the built environment, and pedestrian injury. Among several key findings is that census tracts with the highest concentration of socially vulnerable people (representing 25% of the state’s population) account for 45% of pedestrian injuries.

“It’s important to recognize these disparities and understand the underlying conditions that create them so that targeted and effective action can be taken,” write authors Nathan McNeil and Josh Roll.

Weighing in at a neat 100 pages, the report is comprehensive and thick with statistics — a must-read, go-to-first document for anyone studying pedestrian safety and vulnerable roadway users in general. The extensive literature review alone will be enormously helpful to other researchers and agencies (which are the intended audience given the technical approach and language). Readers may remember that we covered a shorter synopsis of the work ODOT released earlier this year.

Advertisement

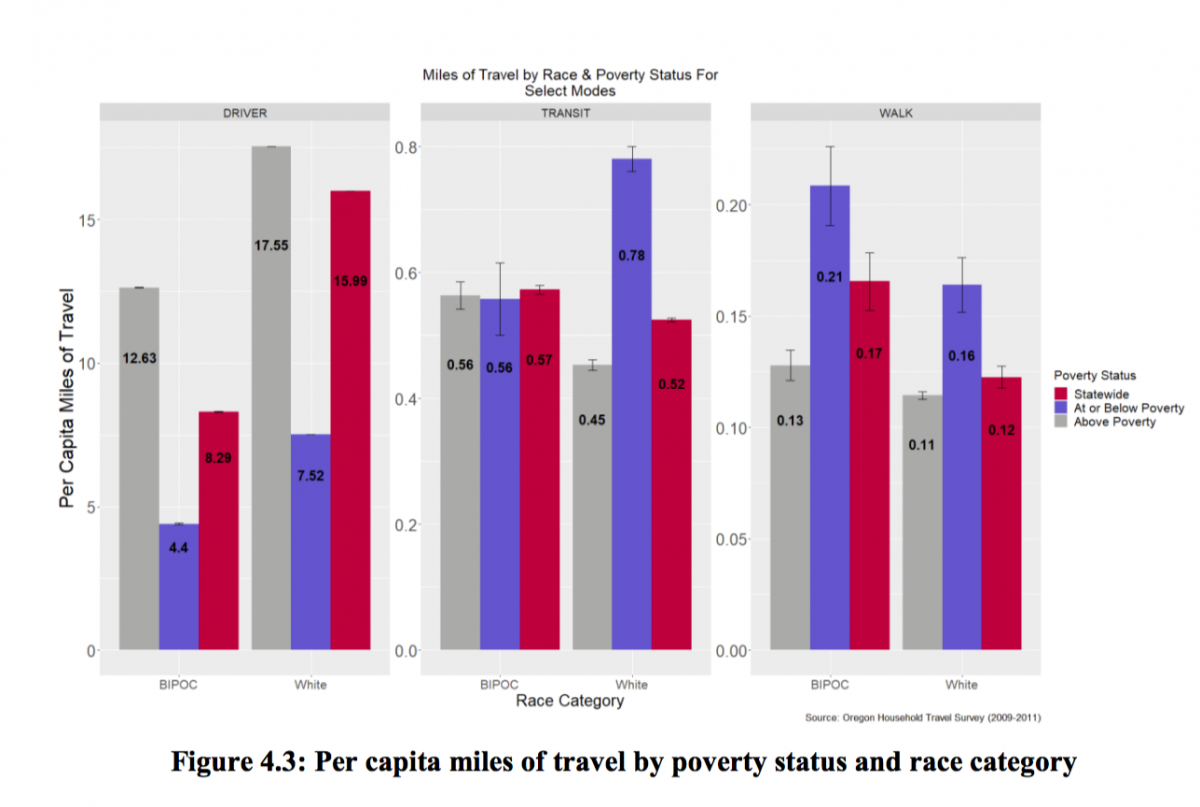

The simplest data to come out of the report show that census tracts with higher percentages of Black Indigenous People of Color (BIPOC) or low-income Oregonians suffer from the highest pedestrian crash rates. Another top line finding is that using public transit and walking to work in high-volume traffic areas are contributing factors in these disparities.

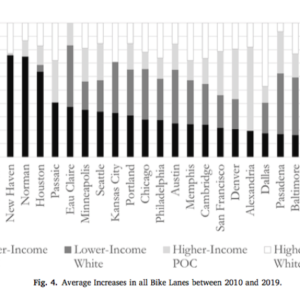

ODOT researchers correlated travel mode with race and income to produce the bar chart on the above left. The chart reveals interesting differences between BIPOC and white people of similar income. Below poverty level, white people are more likely to use transit than BIPOC, but the BIPOC are more likely to walk. Above poverty level, white people drive a lot.

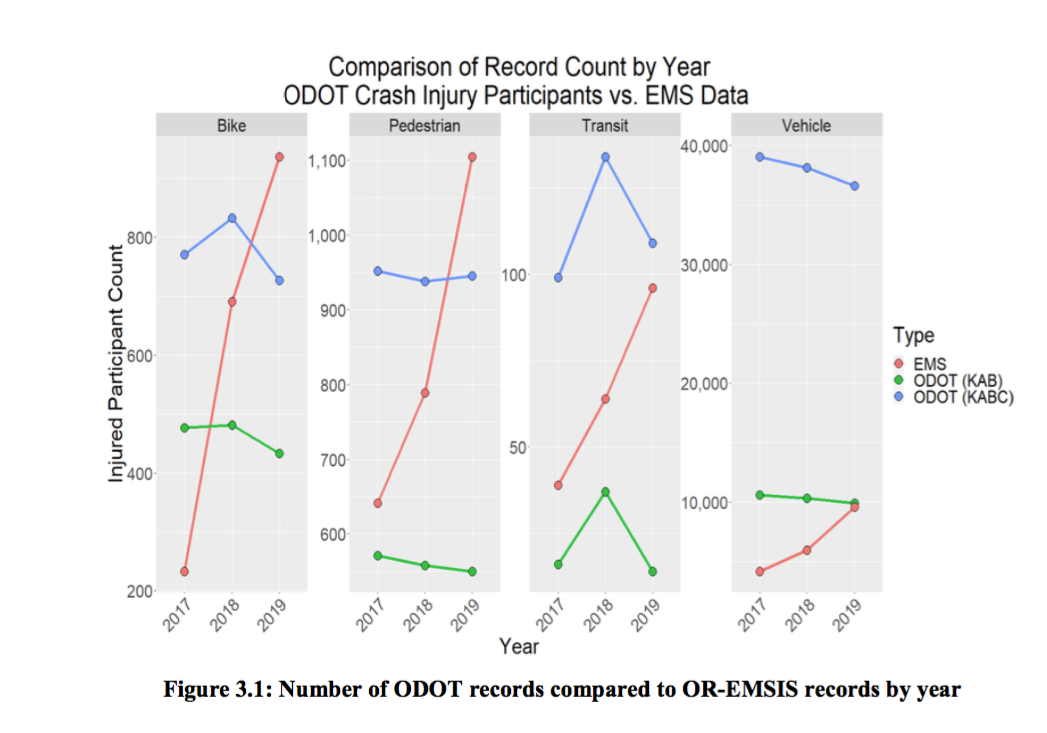

The analyses are based on data pulled from several different public databases: the Fatal Accident Reporting System (FARS) data for Oregon, Oregon Emergency Medical System Service (EMSIS) data, sociodemographic data from the Census, built environment and traffic exposure data, and data from the Oregon Household Activity Survey (OHAS). No single set provided the researchers with the all the data they needed, but correlating the information across sets allowed them to build more nuanced and informative profiles. The report devotes many pages to the technical aspects of integrating this data, and much of it reads like a roadmap for those following in their footsteps.

One unexpected finding that arose out of the redundancy of multiple sources was a discrepancy in reporting between EMSIS and ODOT crash data (above chart). You can see that EMS crashes for people biking and walking rose steeply between 2017 and 2019, but the ODOT crash data was flat or fell. The authors suggest the possibility that the ODOT database underreports pedestrian and cyclist injuries.

In the 30 years between 1988 and 2018 the average weight of personal vehicles increased by 26%.

The analysis largely aligns with previous research from across the country, and is Oregon’s entry into the national conversation. It should become a resource for how funding is allocated. One expenditure the researchers will probably push for is a comprehensive database of active transportation facilities, which the state currently lacks. This prevented them from directly studying the effect of infrastructure like sidewalks and crossing improvements. The Portland Bureau of Transportation’s PedPDX plan built a database of Portland sidewalk coverage and gaps which will give the state a good start toward building their own.

Another challenge for ODOT will be to effectively communicate their results to the local transportation agencies which do not have their deep bench of statisticians and analysts. It is easy to oversimplify statistics to the point of inaccuracy. Many of the findings in this study refer to “low income people and BIPOC populations.” In using these results, it will be important not to ignore the low-income part.

In a document loaded with databases, facts, and statistics, one side point jumped out at me. In the 30 years between 1988 and 2018 the average weight of personal vehicles increased by 26%. The relation between vehicle design and severity of injuries, and whether these effects are experienced equally, are pressing questions for future research, the authors write. Vehicle size is an often unacknowledged barrier to reaching our Vision Zero goals.

— Lisa Caballero, lisacaballero853@gmail.com

— Get our headlines delivered to your inbox.

— Support this independent community media outlet with a one-time contribution or monthly subscription.

Thanks for reading.

BikePortland has served this community with independent community journalism since 2005. We rely on subscriptions from readers like you to survive. Your financial support is vital in keeping this valuable resource alive and well.

Please subscribe today to strengthen and expand our work.

Yes, I have noticed that vehicles are getting bigger. It used to be a fairly uncommon to see a very large pickup truck, or an SUV with a hood that came up to nearly 5 feet. I’m seeing more & more very tall vehicles. It’s scary.

If the electrification of vehicles forces the state to replace gas taxes with per-mile road fees, this is another reason for why they should base the fees on vehicle weight.

“It’s scary.”

psst.. That’s the point.. These vehicles are designed and outfitted to be intimidating.. Towards what end? Idk.. Maybe they just like the power imbalance of imposing a much higher safety risk to others.. Maybe its conspicuous consumption and a way to show off wealth.. Maybe it’s just shallow imitation of cultural trends..

Maybe its more complicated than that, and its a combination of a variety of systemic and individual factors..

Either way.. its toxic, and I blame cyclists and pedestrians for taking up the road. /s

Conservative American males are typically very insecure and *over*compensate by aligning with things that evoke the “frontier” mentality. Big vehicles and guns, in particular.

Cyclist and pedestrian fatalities are probably underreported in the ODOT data base because it is derived from DMV data; motorists are legally obligated to report vehicular accidents to the DMV but there is no similar requirement for cyclists or pedestrians. I have also spent some time in the past looking at PPB/PBOT crash stats and it always seemed to me like incidents involving cyclists and pedestrians were either underreported or misreported in that database.

Agreed. ODOT is not the villain when it comes to official crash data because it is completely handled in a statutory manner by DMV. Oregon is different than almost every other state when it comes to crash data because law enforcement rarely files crash reports unless it is a higher severity crash involving a motor vehicle. In almost every state other than Oregon, law enforcement files crash reports for all crash severities because they are statutorily required to. Not so in Oregon.

Are you suggesting that cyclists or pedestrians should be legally obligated to report vehicular accidents?

ODOT appears to be a little behind the time with this study, Much evidence suggests that class and income are better predictors for assessing justice than race.

https://www.nytimes.com/roomfordebate/2016/01/28/racial-reparations-and-the-limits-of-economic-policy/class-is-now-a-stronger-predictor-of-well-being-than-race

https://www.nytimes.com/2016/02/07/education/edlife/black-america-and-the-class-divide.html

Focusing on race hasn’t made improvements in society for thousands of years, its actually made it worse. Maybe it’s time to forgo this obsession with everyone’s race.

How about instituting double blind (or better) hiring practices? How about the same for financial transactions?

How about instead of focussing on the shameful results and look to solve from the outset? Meaning, eliminating barriers (for all) to education, employment, and housing.

Trying to “fix” the issue after it already has happened doesn’t really occomplish anything other than putting a bandaid on it.

Assessing justice is disappearing across America. Increasingly, criminals caught red handed are simply being released on th spot rather than arrested because of strained police and court budgets and already full jails. Then there are the Capitol rioters, most of whom have had their charges dropped. Crime is becoming the best paying job out there.

Lauro, thank you for the links, the Henry Louis Gates Jr. piece was particularly interesting to read five and a half years after it was written, we’ve been through a lot.

You bring up an interesting point about the relation of class, race, and income, and the inequalities within groups. The BIPOC label does put a lot of cats in the same bag.

I’ve written mainly a news article, I’m not qualified to review the authors’ work. And it’s hard to absorb something this dense solo, without people to discuss it with, or an opportunity to hear the authors in a lecture, and to ask questions. That said, the question I would put to the authors is if BIPOC was a useful construct to them in their analyses.

But that is a narrow statistical/mathematical question. For the sake of argument, assume that the vulnerability findings can be better captured with income data. The more important social question is “Why are so many Black and Indigenous Americans living in poverty?” The answer? Because of past atrocities and ongoing racism. Thus, the disparities are a manifestation of racism, for that reason alone it’s important to track BIPOC as best you can.

The Limitations and Future Research sections address this a little. The authors write:

The point I was trying to make at the end of the article is that people get sloppy when re-presenting statistics, what I see most often is a logical fallacy of transferring a general result to specific case. Taking an example from an easier article, just because you can’t prove in general that bike lanes cause gentrification, it doesn’t mean that somewhere a bike lane didn’t lead to gentrification. But you wouldn’t have the statistical power to show it.

“Because of past atrocities and ongoing racism. Thus, the disparities are a manifestation of racism, for that reason alone it’s important to track BIPOC as best you can.”

This is hardly a cut and dried conclusion. There are dozens of BIPOC groups who’s median income surpasses whites, including Ghanian and Nigerian americans, and even more who’s median income is roughly the same.

False. You’re citing recent immigrant groups and the comparison is inapt.

That’s why I would ask the researchers if “BIPOC” was a useful construct for them, (above) it “does put a lot of cats in the same bag.”

I’ll show my cards, I don’t like the term “BIPOC,” I think it obscures important distinctions.

Great article Lisa. I really appreciate the analytical approach.