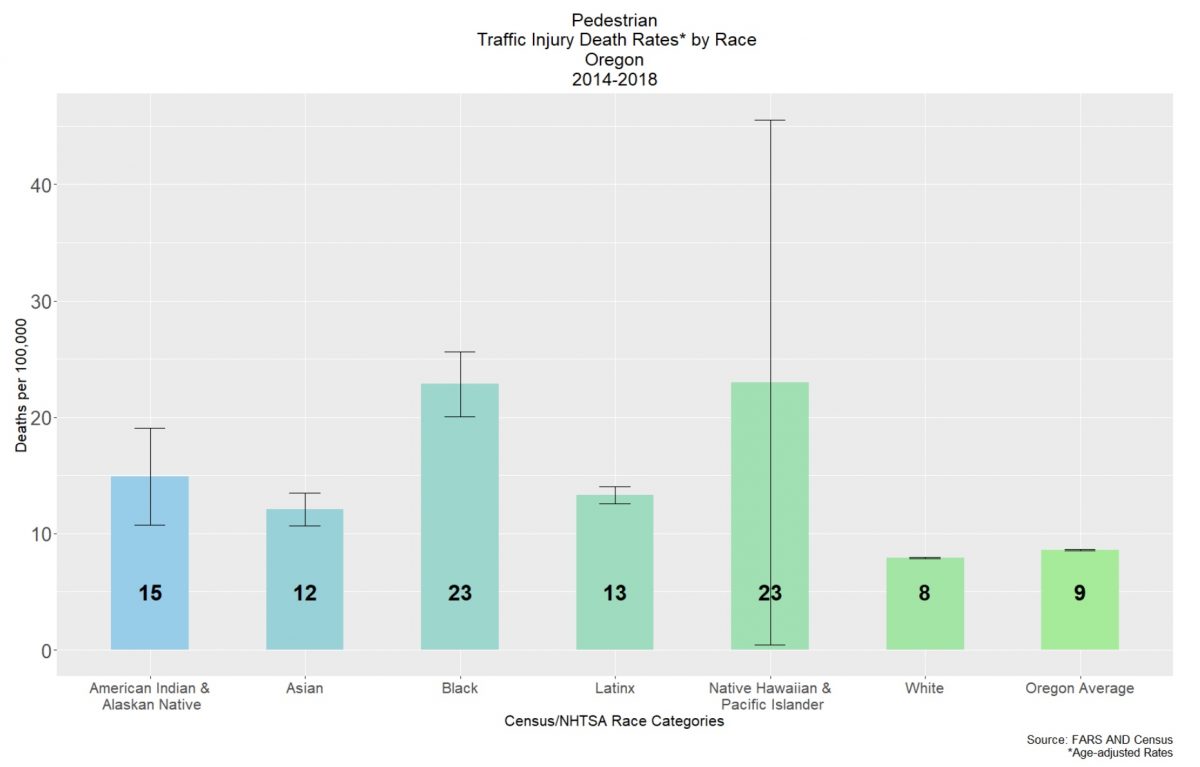

A growing body of research has proven that incomplete and dangerous transportation infrastructure in lower-income areas has a disparate negative impact on Black, Indigenous and people of color. Now ODOT’s own analysis proves the existence of these impacts on BIPOC Oregonians for the first time.

The Oregon Department of Transportation has released a groundbreaking new technical memo titled Pedestrian Injury and Social Equity that draws a line between injury and fatality rates of non-drivers and the racial, income and geographic makeup of crash victims.

“It’s important to recognize these disparities and understand the underlying conditions that create them so that targeted and effective action can be taken,” reads the opening of the 18-page memo written by Josh Roll, an active transportation researcher at ODOT.

Advertisement

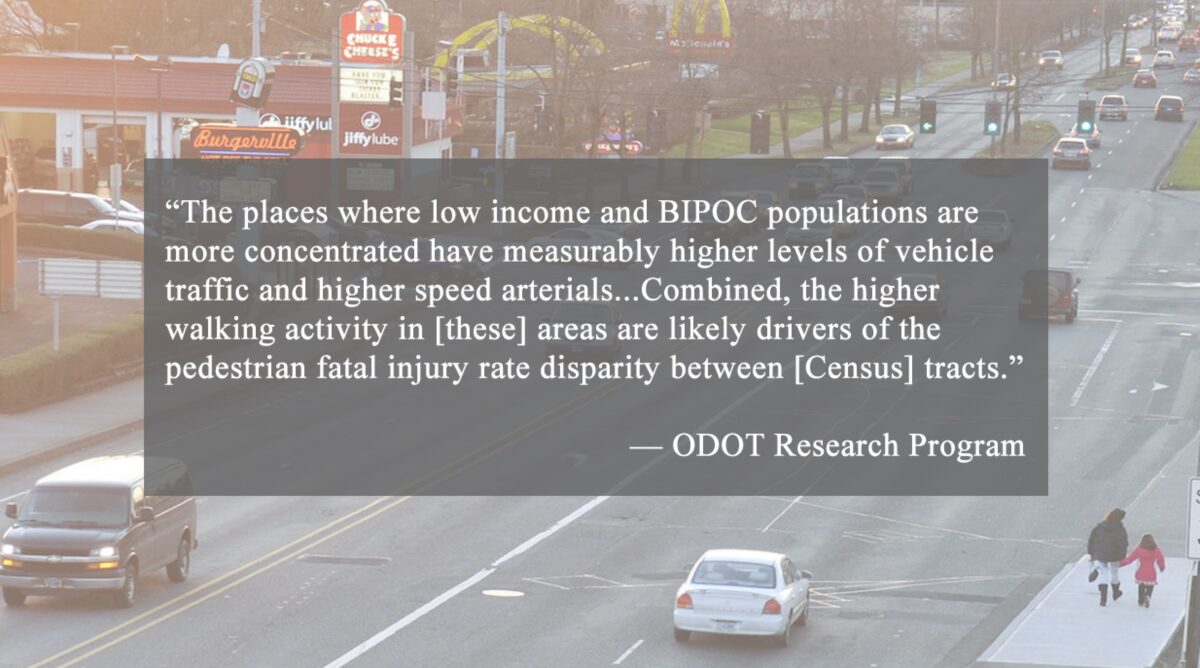

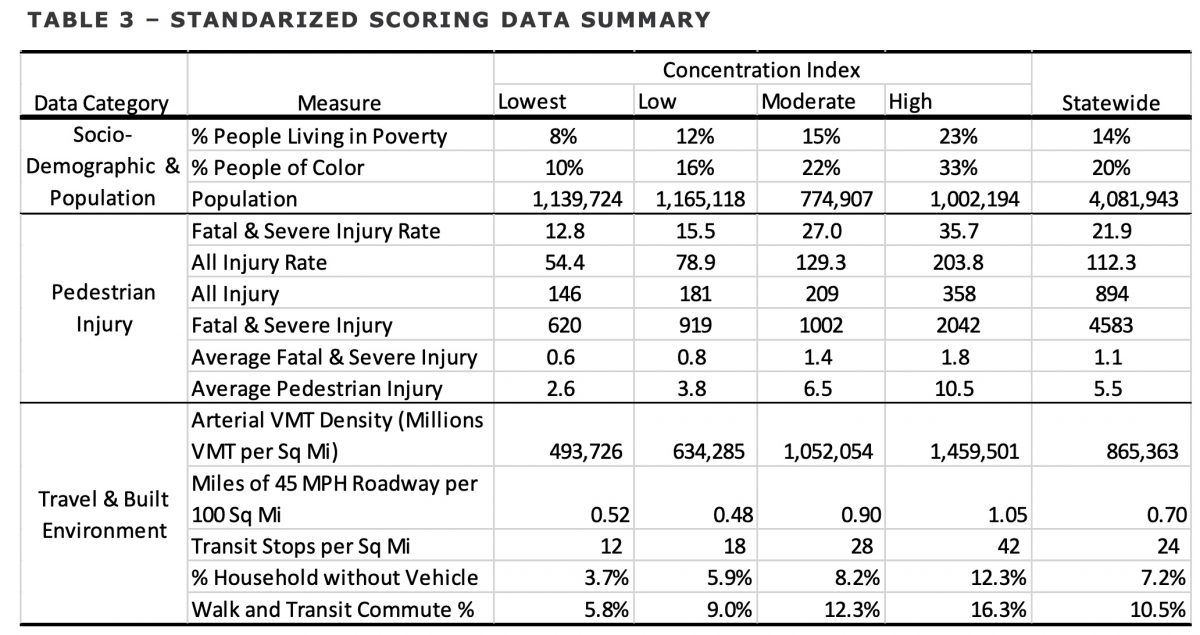

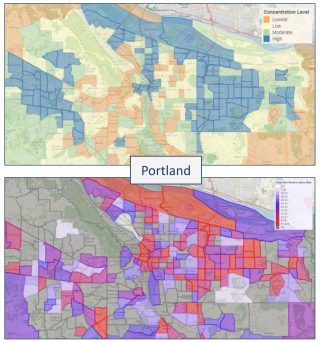

Roll and his team cross-referenced income, race, and crash data with Census tracts of Portland, Medford and Salem and found that places with a higher concentration of people of color and poverty are much more likely to suffer injury or death while walking.

“The segregated housing landscape contributes to different transportation experiences, travel options, and safety conditions.”

— ODOT

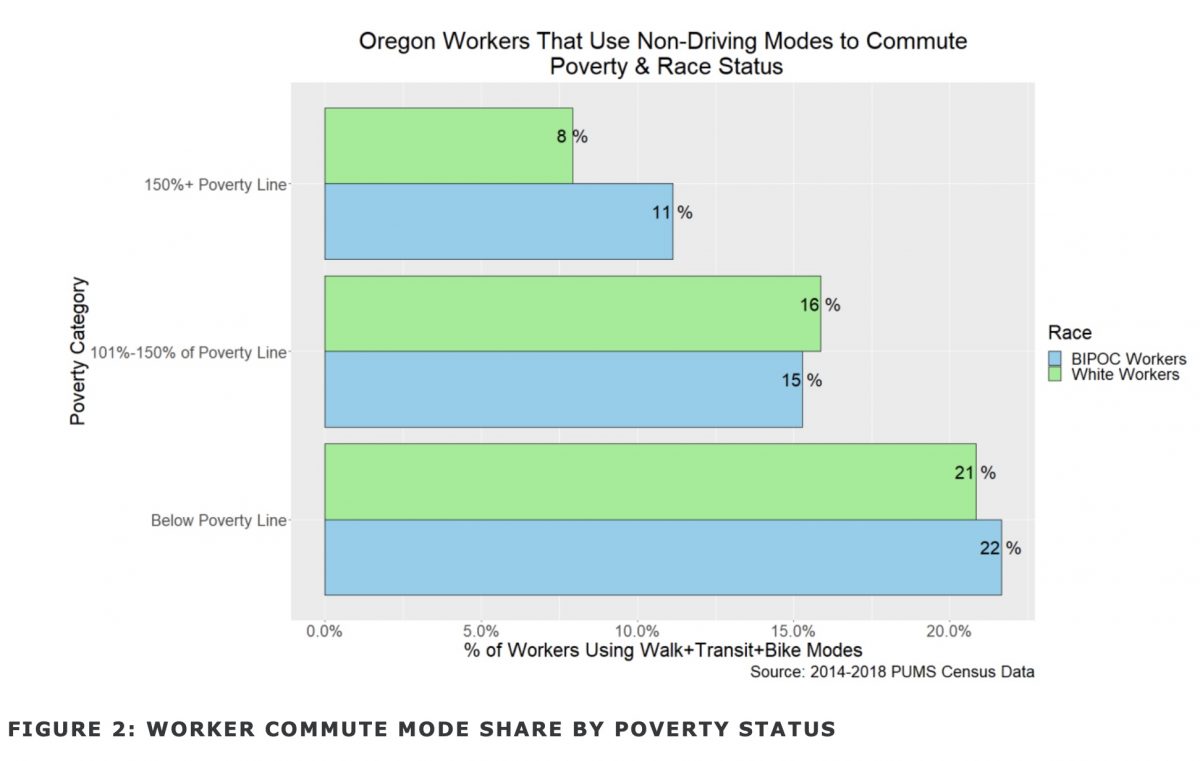

“People who are low income and/or BIPOC are more likely to walk and take transit [due to the high cost of auto ownership], meaning they have greater exposure as pedestrians to traffic safety risks,” states the report. “Further, they are more likely to walk in environments with higher vehicle traffic volumes, less street connectivity, and fewer pedestrian safety features like sidewalks and crossings. These factors combine to result in higher pedestrian fatal injury rates for these groups.”

It’s important to note that because income of crash victims isn’t included in federal or state data, ODOT did a separate analysis of neighborhood characteristics to quantify the role poverty plays. This “ecological analysis approach” is a limitation of the research.

While ODOT’s research finds a direct line between race, income, geography and crash data; they weren’t able to analyze how the lack (or presence) of certain types of safety infrastructure — like sidewalks and crossing treatments — impact injury and fatality rates. That’s because ODOT still has no comprehensive database to track this type of infrastructure statewide.

The study also took into account how a “segregated housing landscape contributes to different transportation experiences, travel options, and safety conditions.” “Land use and zoning policies, home lending practices, and housing affordability have all contributed to income and racial differences in housing locations,” the report states.

Advertisement

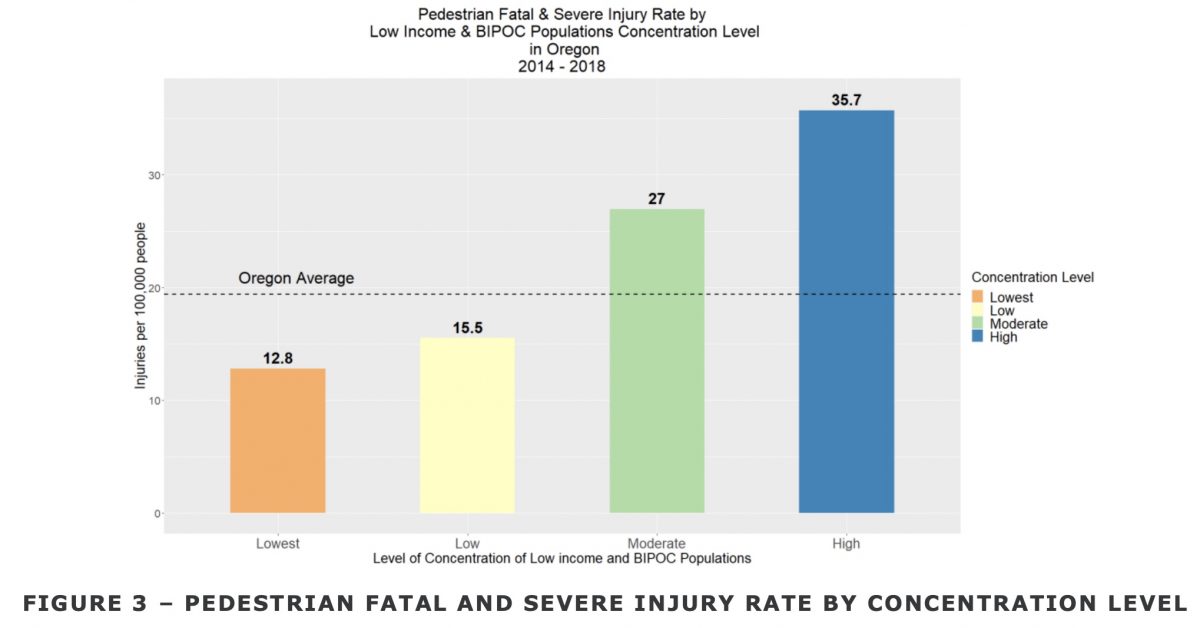

According to the research, about 24% of the total Oregon population live in a Census tract designated as having a high concentration of low income and BIPOC residents, but have about 40% of the total injuries. The fatal and severe injury rate for people walking in Census tracts classified as “high” in ODOT’s concentration index is over two times the rate in the lowest category and 63% higher than the statewide average.

A big reason for the higher impact on low-income and BIPOC residents is what ODOT refers to as a “harsh” transportation environment. “The average arterial vehicle miles travel (VMT) density in tracts classified as high is nearly three times higher than the lowest category and about 68% higher than the state average,” the report reads. “There are nearly twice as many high speed roadway miles per square mile compared to the lowest index category.”

Now that ODOT’s own data aligns with existing research, this information should be used to inform investment decisions. As mentioned above, it should also create urgency to develop a comprehensive statewide database of infrastructure like street lights, sidewalks and traffic calming features so those gaps can be filled as soon as possible.

ODOT’s findings come just weeks after Multnomah County released a report with similar findings.

Learn more by reading the full memo here (PDF).

— Jonathan Maus: (503) 706-8804, @jonathan_maus on Twitter and jonathan@bikeportland.org

— Get our headlines delivered to your inbox.

— Support this independent community media outlet with a one-time contribution or monthly subscription.

Thanks for reading.

BikePortland has served this community with independent community journalism since 2005. We rely on subscriptions from readers like you to survive. Your financial support is vital in keeping this valuable resource alive and well.

Please subscribe today to strengthen and expand our work.

This is why I read bikeportland. Amazing and baffling to read research like this, look at street design priorities, and know they come from the same organization.

yes it is a bit bewildering when you realize how large and disconnected the ODOT bureaucracy is. Some sections and programs are really awesome and doing great work with progressive-minded people… But the heavy-hitters doing the big freeway/highway expansion stuff are still stuck in the 1970s it seems.

I presume ODOT representatives will proactively bring this to the attention of the Joint Transportation Committee considering the Safe Routes for All Act, as a clear and evidence-based example of how the current broken funding system is maintaining those harsh transportation environments for BIPOC communities.

/snark

People live where they can afford to. The cheapest areas have the worst services and they tend to be the most dangerous places.

Yes, this is the current situation but was not always so…

[I remember moving into downtown Vancouver in the late 90s – when it had more main street retail services and transit with sidewalks but had not been gentrified by several waves of Portland resident flight so was more affordable than the suburban apartment areas with less of the all the amenities…except free off-street parking.]

PS. Only the beer and coffee is better now, plus bike lanes…I do miss the pull tabs and low bars. And as of this weeks’ news…New Seasons will arrive soon – 2023.

Isn’t it remarkable how much downtown has changed?? My first solo apartment when I was a young PTB was in the mid 90s, at 19th and Columbia. It was so quiet down there back then. The coffee and beer is much better now, for sure. I almost wish we had bought our house over there than outer SE, but those bridge crossings would have gotten pretty old, pretty fast.

??? So you’re arguing that economics didn’t always play a major role in where people live, yet then cite an anecdote about moving to Vancouver because it was more affordable than suburban living? Am I missing something?

“The cheapest areas have the worst services[.]” That’s a policy decision.

Another form of environmental racism, and one that hadn’t occurred to me. Great reporting.

The ODOT announcement we all want to see:

“Based on the study we just completed, we are halting the I-5 Rose Quarter expansion project, due to its disproportionately negative impact on Communities of Color.”

So what ODOT needs to do is reroute the freeway expansion through predominantly white and wealthy areas like Irvington?

That would probably result in mitigating design and alternatives.

No, what ODOT needs to do is to not do the expansion.

But leaving the freeway as is, 8 lanes and all, is OK? Because it’s still a lot of whites driving on a freeway that doesn’t benefit the blacks who still live along it, it fact it makes their lives miserable with the noise & air pollution. Wouldn’t it be better to close the I-5 altogether and reroute the huge amount of traffic through those parts of town that benefit most from it?

Exactly, David – I’ve been saying it all along: Take out I-5 in NoPo and make it into a city street (with park, cycling lanes, etc). I-5 bridge becomes a local bridge. Then turn Hwy 30 into I-5 and put the eight-lane CRC near St. Helens. Solves every problem.

I rarely bookmark articles, but this one deserves it. Kudos to ODOT to putting this together (now follow through on some action plz) and JMaus for reporting on it.

I was about to type, “I couldn’t agreemore with this…” But as I started to, I realized this isn’t something to agree/disagree with. These are facts! A very tight summary of the state of affairs, with a very unfair (sheesh, often deadly) outcome.

Exactly, Silky. Yes, research can be somewhat biased, it can have weak methodology, and it can even use statistics to mislead (none of which I’m suggesting here).

But it can also point to a body of converging evidence on a topic that can and should inform policy. I wish op-ed (which at one point perhaps represented critical thinking) would be replaced with “recent evidence.” Science is not flashy, and almost never has solid conclusions, but it leads to informed choices… or that’s my hope.

Ok, being even more cynical than usual. They really needed a study to tell them that poor areas of Portland (and other cities) don’t get the money and projects that the wealthier areas do?

Just driving around town tells me that every day.

I guess I just want to say to ODOT….

DUH!

Yes it a “duh!” moment, BUT ODoT is a ‘large’ agency and geographically diverse too…it is more difficult for a public agency to ignore its own studies than those of an outside group. Generally agencies only collect data on the problems it is interested in addressing…no data = no problem.

So this is the third big step…of a “12 step” type program. They identified the need for such research #1), someone with authority approved its budget (#2) and then they released the information to the public (#3). No “we” the public and its partners need to help them work on the next 9 steps.

It’s a lot more nuanced than that. For example, East Portland used to be a rich mostly white part of the county, but over the 3 decades after Portland annexed it and neglected to make any improvements to it, the area has become the poorest part of the city; whereas simultaneously the Albina District of north-central (NE) Portland has gone from an overbuilt blighted part of the city with a predominantly Black population to being an even more overbuilt over-gentrified part of the city with hardly any Blacks left. The infrastructure in both places didn’t change nearly as much as the economics and demographics – the inner neighborhood became gentrified partly because it was always walkable, but mostly because the city suddenly (in the 1990s) chose to reinvest into the community. The opposite happened in East Portland – the lack of city investment there gradually made living there more hellish as more people moved in, but more people moved in because relative to the rest of Portland it was far more affordable.

It’s one of the dilemmas in urban planning: if you make an area livable, you often in turn make it unaffordable to the residents still living there. And to have a healthy self-renewing community, you need a balanced mix of incomes, living environments, and jobs. By fixing up one part of town but deliberately neglecting another part, you create a downward spiral of urban decay rather than urban renewal – your developers get rich on the backs of the poor who have to keep moving.

Isn’t the bigger force that people found urban environments more appealing and suburban ones less so? I think market forces dwarfed any “neglect” of the more suburban neighborhoods by the city of Portland.

ODOT’s project on outer Powell is a good start in addressing the issues, but there’s a lot more that needs to be done. I will not blame ODOT for any of the roads that it wants to transfer to PBOT — who refuses to take the roads — like 82nd, but roads like TV Highway and the northern section of MLK that should be immediately made safer.

However, looking at the map it seems that this is again mostly a PBOT problem. The only ODOT-controlled road that passes through the giant section of east Portland is Powell, which ODOT just spent a ton of money on to make it safer. And the other area of high concentration, around TV Highway where most roads are maintained by WashCo, is significantly safer than East Portland despite also having a high concentration of low-income and POC people. The moral I take away from this story is that it is PBOT, not ODOT, who is failing its low-income and POC residents.

Eh, it’s not that simple. For decades, ODOT has never prioritized or done much improvement to its so-called “orphan highways” throughout the region while they always seem to find funding for freeway expansion. It will cost hundreds of millions collectively to improve these roads, money that cities and counties don’t have, won’t be able to raise and frankly, shouldn’t have to pay. And even if PBOT could find a way to fund fixing 82nd, et al, what about say, 99W through Tigard? How do smaller cities raise the revenue?

Based on death/injury rate, it’s pretty clear that it’s both. PBoT has a lot of well-meaning employees who care about safety and a lot of safety advocates give PBoT the benefit of the doubt. PBoT policy continues to prioritize traffic counts and parking on almost every project. Eudaly blamed ODoT streets and the glacial procurement process for the record number in death/injury since 1996. But the primary cause of this record number of death/injury on PBoT roads continues to crystal clear: PBoT’s means for evaluating streets is inherently skewed toward maintaining (not reducing) car capacity and parking. This process of evaluation does not seem to be questioned by advocates or the new commissioner.

I think you could accurately say that over the last several decades in Portland, ODOT has spent money building roads so people in wealthier neighborhoods can drive more conveniently through less wealthy neighborhoods to get where they want to go. A lot of ODOT money has been spent in poor neighborhoods, but it has gone to serving wealthier people driving through them.

An example is MLK Jr. Blvd, which was rebuilt in the 70s to remove parking that the street’s businesses needed, and add medians that allowed people to drive through faster, but at the expense of neighborhood auto and pedestrian traffic.

When ODOT spent this money, it then led to those neighborhoods (like those along MLK) deteriorating faster than if it had done nothing.

So ODOT bears a lot of responsibility for not only creating the higher-speed roads that are dangerous to walk along or cross, but also for making those neighborhoods those roads are in poorer by destroying their “main street” businesses and their livability.