The latest effort to built a new, wider freeway between Oregon and Washington is called the Interstate Bridge Replacement Program (IBRP). It’s been nearly seven years since the last effort (the Columbia River Crossing) died and project staff are once again barreling down the highway. While electeds and staff are giddy, at least one key elected official is urging restraint.

Last week the IBRP launched a slick new website and social media channels. At a meeting of the project’s bi-state Executive Steering Group (ESG) yesterday, Program Administrator Greg Johnson seemed downright excited. “I told you before we were walking fast. We’re going to start running at this point,” he beamed.

Johnson and other project backers are especially gung-ho because Washington lawmakers just introduced a $26 billion funding bill with $1 billion set aside for the IBRP — the only project to receive an earmark. “That’s billion with a ‘b’ dollars and we’re absolutely ecstatic about that,” said Vancouver Mayor Anne McEnerny-Ogle.

Advertisement

In a nod to this project’s size and import, the ESG is staffed by heavy-hitters in the transportation and political worlds on both sides of the river. DOT directors from both states, transit and port authority leaders. There are even bipartisan legislative committees in both Oregon and Washington assembled for the sole purpose of making the project happen.

Mayors from both cities are also on the ESG; at least that’s the plan. McEnerny-Ogle is already on board but for some reason Portland is yet to name a representative. Mayor Ted Wheeler sent his Chief of Staff Sonia Schmanski to the meeting yesterday. She said they haven’t figured out if it will be Wheeler or Portland Bureau of Transportation Commissioner Jo Ann Hardesty on the committee. It’s unclear if this is about scheduling or if it’s just delaying the inevitable: Hardesty and Wheeler must know this project is likely to be highly controversial.

(Photo: Jonathan Maus/BikePortland)

Metro President Lynn Peterson seems to grasp that fact very well. That’s probably because she has a few battle scars from the Columbia River Crossing. Peterson was Oregon Governor Kitzhaber’s transportation policy advisor in 2011 and went on to become head of the Washington Department of Transportation. Peterson was only at WashDOT for the tail-end of the CRC debacle but she’s been around local transportation politics for over 25 years.

After IBRP Administrator Johnson’s jovial “we’re running” comments at the outset of yesterday’s meeting, Peterson was quick to throw on some cold water. “While we want to see the bridge replaced, we want to see it done at a pace where everyone can be brought along and make sure we get consensus as we move forward,” she cautioned. And that was just the first of several remarks that show she’s playing it cautious so far.

At two key points in the meeting, Peterson warned ESG members of the perils of repeating mistakes from the past. Both warnings were related to how assumptions about design and cost might lead to an outcome that is too driving-centric (and therefore, controversial). “I think we really need to go back and look at those underlying traffic forecast models that we did because it will impact how we craft the ‘Purpose and Need’ [a reference to a required section of the federal NEPA process that will dictate which design alternatives can be studied].” Peterson is worried that faulty traffic projection data will lead to sharp criticism from advocates and stakeholders. “It’s really important to look back at the assumptions that were made back then [during the CRC process],” she added. “We had challenges to the basic underlying traffic forecasts and travel assumptions… we’re gonna get a lot of questions about that.”

Advertisement

At another point in the meeting Peterson raised a caution flag about cost estimates. The cost of the project was the straw that broke the back of the CRC when Washington lawmakers balked at paying their share ($450 million) of the estimated $3.4 billion project. In yesterday’s meeting, Peterson pressed project staff about how the highway portion of the project will influence cost estimates.

While the DOTs want everyone to think this is about replacing one bridge (because it makes the PR and politics easier), the project is also about expanding I-5 and building larger freeway ramps on both sides of the river. Despite the focus on the river crossing, non-bridge highway elements (which included not just more and wider lanes but three park-and-ride lots with a total of 2,900 new car spaces) of the CRC were estimated at about 40-45% of the total project cost.

Peterson seems to understand that the scope and cost of the non-bridge elements of this project will be pivotal to the project’s success — or failure.

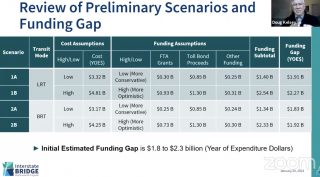

In response to a funding chart presented to the ESG that showed a high and low estimate for transit costs (but not for the highway), Peterson said, “What I’d like to see going forward are practical design options for the highway portion and how that’s affecting the cost… I think, in order to be able to afford this… we need more options on the table than just having a high and low transit option. We’re going to need high and low highway options to pair with them.”

Just like last time around, we’ll be watching this project closely. Stay tuned for coverage as the process moves forward.

— Jonathan Maus: (503) 706-8804, @jonathan_maus on Twitter and jonathan@bikeportland.org

— Get our headlines delivered to your inbox.

— Support this independent community media outlet with a one-time contribution or monthly subscription.

Thanks for reading.

BikePortland has served this community with independent community journalism since 2005. We rely on subscriptions from readers like you to survive. Your financial support is vital in keeping this valuable resource alive and well.

Please subscribe today to strengthen and expand our work.

IBRP, aka the “I BURP,” promises billions in freeway gluttony to yield a giant belch of greenhouse gas.

The last plan called for two park-and-ride garages near 4th and Washington streets in Vancouver. Hopefully any future plan is better thought out. It doesn’t make sense to have all those cars driving through downtown to get to the lightrail station.

Rather than a “low transit” option, why not a “low emissions” option?

And of course this project will be used to justify the Rose Quarter freeway expansion.

If you want to reduce congestion and VMT within Portland, the best place to reduce flow is at the bridges – reduce the car-carrying capacity, not expand it. Replace car lanes with light rail, BRT-only lanes, and protected bike lanes. Widen sidewalks enough to allow pocket parks, cafes, and nice viewing points.

I believe you have it backwards; the Rose Quarter project addresses a major stumbling point of the previous CRC project, namely capacity closer to Portland. With the RQ underway, it is easier to justify a more massive project across the Columbia.

We need some politicians who can actually change the outcomes on these projects, rather than talking about how awful they are while having their agencies support them. Peterson and Eudaly are two such enablers who come to mind.

Chicken and egg issue. Neither interstate should be widened, but the congestion issues in one location will be notably affected by a project in the other location.

Studies in the 1990’s identified three issues in the I-5 corridor: the two-lane section of I-5 southbound near Delta Park; the old, deficient I-5 bridge; and congestion and safety issues in the Rose Quarter area. The Delta Park widening was accomplished several years ago. To suggest that the I-5 Bridge and Rose Quarter projects are newly discovered problems that are being used to justify each other is in error.

Why not slightly redo the nearby BNSF (UP?) railroad bridge so that its swivel point will be moved to the south so that boat traffic will less often ask for a bridge lift? Use logic, save money, and stay with a bridge(s) that is still good?

This is part of the common sense alternative. The railroad bridge in question is the oldest span on the Columbia and is absolutely critical for rail traffic on the west coast.

Yes!!

Are they even discussing the CSA2 or similar designs? Smart people have proposed creative solutions for less $$ and better outcomes

One thing I remember from last time around: as a share of overall project costs, it wasn’t much more expensive to rehab the existing bridges than to take them out. Any plan should start with a smaller (and thus much cheaper) freeway bridge than previously proposed — just three lanes each way — and use the current bridge spans for local traffic, transit, bikes and pedestrians.

The CRC was ridiculously overbuilt.

1. Keep the downstream span, which is the newer of the two for transit/ped access, and demo the 1917 NB span.

2. Replace NB span with simple 8-lane span for I-5 traffic.

3. Close the Hayden Island interchange. You now have 8-lanes of unobstructed flow from Marine Drive to Vancouver without having to replace the I-5 span south of Hayden.

4. Build local access/transit/ped bridge from Marine Drive over to Hayden Island. MAX extension uses this bridge and the repurposed SB I-5 span to get into downtown Vancouver.

5. Rebuild and expand downstream railroad bridge (4 tracks) to eliminate S-curve movement for boats, reducing lifts on the remaining I-5 span. Future capacity for additional regional commuter rail and Amtrak service.

Do we reduce I-5 traffic to one lane each way on the SB span during the 2-3 year construction period of the new 8-lane span?

That’s one option, or it could be built just upstream of the existing NB span, which could then be demolished after the new span is in use.

Which brings me right back to a six-lane freeway bridge and rehabbing both old spans to provide additional capacity. Why knock out an old bridge if you can upgrade it instead?

I don’t believe it is possible to retrofit the existing bridges to permit them to survive a Cascadia Subduction earthquake. This style of lift span bridge will destroy itself in a large earthquake (counterweight movement high in the structure).

So that means we need either a new local access bridge from Hayden to Vancouver, or a new I-5 bridge. I think we should keep the newer of the 2 old bridges.

Also, the bridge foundation is unanchored redwood pilings. In a Cascadia quacke, the best case scenario is that the bridge slides sideways off the pilings and falls into the river intact. (This still kills anyone on the bridge as the river is 42 ft. deep.)

I-5 needs to be moved to US 30, and the new, larger bridge built downriver near St Helens. Folks in Columbia Country will welcome the economic boost provided by the new freeway. You can never build the right bridge in the current location b/c of PDX airport, which cannot be moved. But a bridge can.

The portion of I-5 going thru North Portland can then be demolished (from I-84 north), with N-S thru traffic moving on what is now I-405 but also I-84 to I-205. The 1915 bridge can be demolished and the newer span retained and improved for local traffic but especially for transit.

Save the $800M that would otherwise be spent on the Rose Quarter widening project and apply it to the new I-5.

Planners really aren’t thinking about crossing the Columbia in the right way. But they still can. You read it here first.

You will need massive upgrades and improvements to 30; it’s a rural secondary road with a lot of cross traffic. We really do not want to overload it!

This idea has some merit, but we need to be careful. The failed CRC showed us the folly of relying on one centralized project which does not lend itself to flexibility. The CSA has flexibility built in, presumably with studying the effects at each step.

The missing first step here is congestion pricing. This provides an impetus for people to avoid traveling through the central city. I do think it would be worth studying the effects of a freight bridge north of the St John’s Br. This would allow the calming and pedestrianization of two lanes of the St John’s Bridge and its East end. Redeveloping 30 would also lend itself to a protected cycletrack, making it a feasible commuter route. I hope if we learned anything from the CRC it is this: rely on reliable data, multi-modal transit, and built in flexibility.

As a Vancouver resident, I have to say–if it’s at all possible, make sure that the far right wing transitphobic state legislators from northern and eastern Clark County have NO say in this project, otherwise it’ll have 30 lanes, no sidewalks or bike accommodation and absolutely no possibility of BRT or light rail!