The five-year progress report for the Portland Bicycle Plan for 2030 is five years overdue. That seems like a fitting allegory for the general lack of urgency and institutional respect for cycling in Portland city government right now.

At last night’s meeting of the PBOT Bicycle Advisory Committee, city bicycle coordinator Roger Geller unveiled a draft of that five-year status update. The report details steady progress, but it also reveals our incremental steps forward aren’t nearly enough to reach our goals.

“It’s extremely discouraging to see this lack of progress over a decade,” BAC member Catie Gould said during a discussion that followed Geller’s presentation. “This report should be an alarm bell. We’re never going to hit our goals at the rate we’re going.”

“This report should be an alarm bell. We’re never going to hit our goals at the rate we’re going.”

— Catie Gould, Portland Bicycle Advisory Committee member

The plan’s top line goal is to have 25% of all trips made by bicycle by 2030 and it included 223 action items to get us there. The report says PBOT has completed just 59 action items (26%) and is currently working on 88 (39%) of them.

When it comes to progress toward our bicycle use goal, the results half-way toward 2030 do not look good.

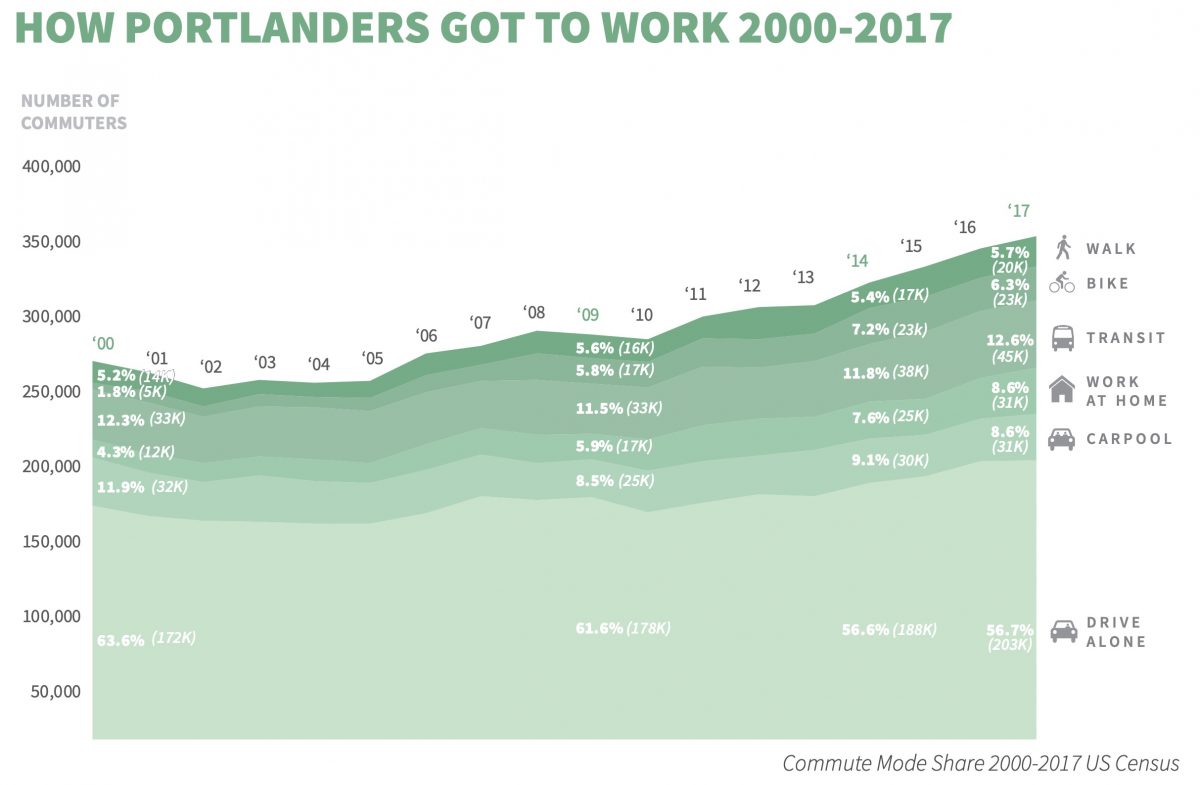

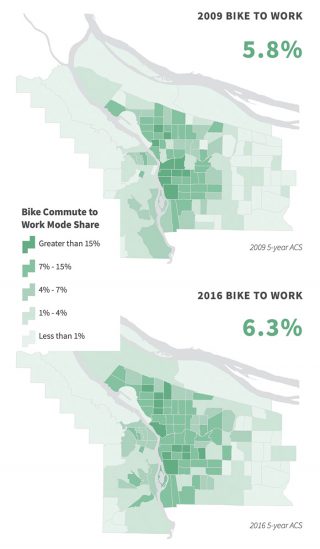

According to the US Census, the percentage of Portlanders who biked to work in 2009 (the year before Bike Plan adoption) was 5.8%. In 2017 that number had barely budged to 6.3% after hitting a peak of 7.2% in 2014. That’s the “extremely discouraging lack of progress” Gould referred to in her comments above.

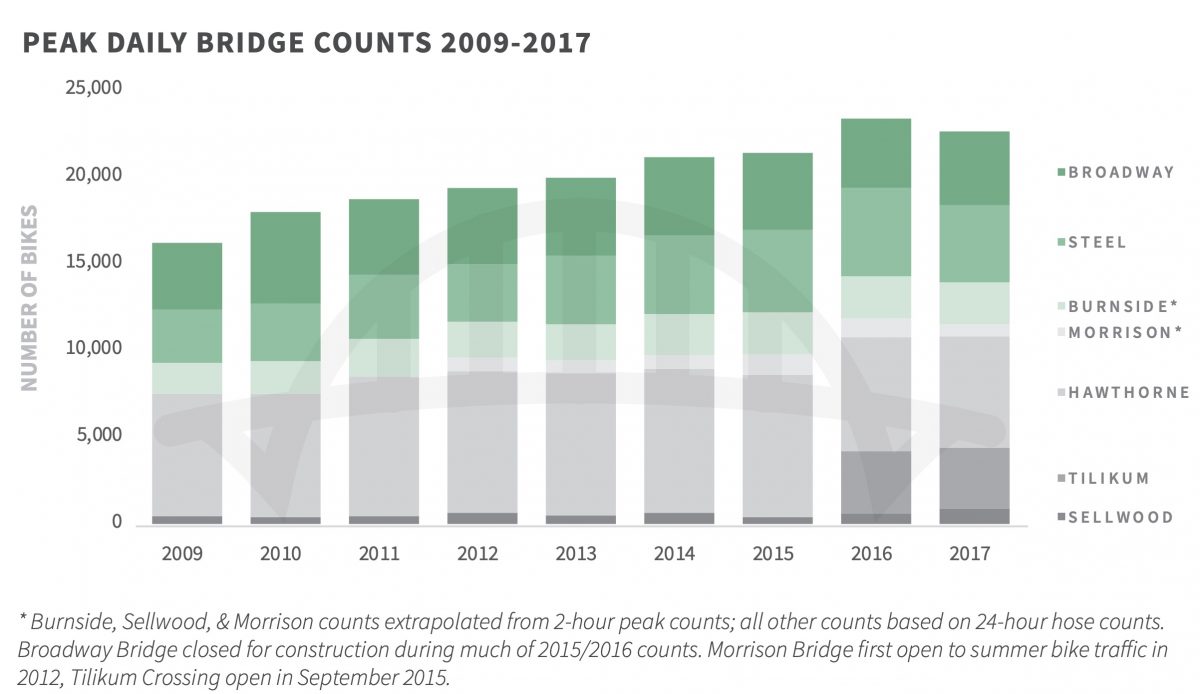

Another area of concern in the report came via a chart that tracks the number of bicycle riders who cross Portland’s main downtown bridges. This is one of PBOT’s most cherished stats and something they’ve used to tell the story of our success for many years. As you can see below, the total number of bicycle trips across the bridges ticked down in 2017 for the first time since records have been kept.

The Bike Plan was supposed to catapult Portland to the cycling promiseland. It outlined three main approaches to get us there: strong planning policies, ample infrastructure investments, and persuasive encouragement programs. We’re doing an OK job at all three. The problem is we’re not doing enough of it and much of our cycling infrastructure is so watered-down by the time it gets built that it fails to inspire the masses — or even the portion of the masses who remain “interested but concerned.”

(Photo: J. Maus/BikePortland)

While the Bike Plan is an important tool, we can only ask so much of it. That’s because much has changed in the past 10 years. When it passed in 2010, the discussion about how race and economic status impact bicycle planning — a.k.a. equity — was in its infancy. Since then, equity has become PBOT’s most important organizing principle. At a recent event, PBOT Director Chris Warner remarked that equity was his agency’s “north star”.

From an infrastructure standpoint, protected bike lanes were still rare in the United States when the Bike Plan was adopted whereas today they’re considered (by advocates at least) a bare minimum. “Build it and they will come,” was the prevailing mantra in 2010. Now we know it’s not that simple. There are myriad reasons why some people don’t ride — from fears of verbal or physical harassment and not having anywhere safe to ride or park their bikes, to fears of unfair treatment from police. That being said, a basic network of safe and connected cycling routes is a pre-requisite for reaching our goals (Commissioner Amanda Fritz referred to cycling as a “basic service” prior to voting for the plan back in 2010). And on that front, even Geller acknowledged at the meeting last night that, “We can do more.”

Advertisement

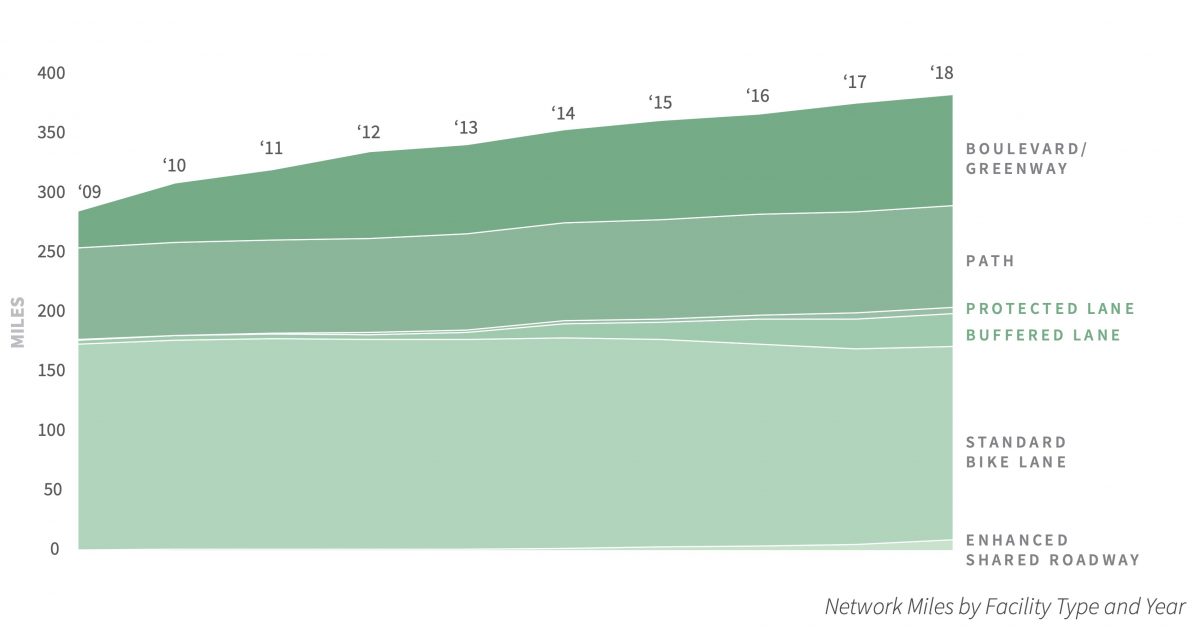

The 2030 plan identified 681 new miles of bikeways we needed to build in order to have a “cohesive, dense network”. In the last 10 years we’ve built just 99 miles of them (with 90 more miles funded for the next five years). The plan split the bikeway implementation strategy into three categories: “Immediate”, “80%” (where 80% of Portlanders would be within a quarter-mile of a “low-stress” bikeway), and “World Class”.

Geller says we’ve built and/or funded 58% of the Immediate and 80% network, but just 28% of the World Class network.

Beyond infrastructure, Portland’s increase in housing prices has had a major impact on cycling in the last decade. As many people have left the more bike-friendly core neighborhoods, they aren’t likely to bike as much when faced with longer commute trips and more stressful conditions. Maps shared in the progress report (at right) show a “decentralization of bike commuters” from the inner core to neighborhoods further out.

A bright spot in the progress report is how PBOT has stitched together our existing network and built more bikeways outside the central city. “In 2009, Portland’s bike network was sparse and highly concentrated in the inner neighborhoods of the East side,” the report reads. “Today, Portland’s bike network includes a much more dense array of neighborhood greenways and buffered or protected facilities there are numerous projects funded

for construction to bring this same connectivity to the neighborhoods east of I-205.”

Below is a look at 10 years of Portland bike network progress in the central city and citywide:

BAC member Iain Mackenzie told Geller Portland should look to Seattle for inspiration on how to guarantee more bikeways get built. Last week Seattle City Council approved a new policy that says if the Seattle Department of Transportation begins a major road project and chooses to not build a bike lane identified in the city’s bike lane, the DOT must bring the project to council and explain why.

“If Portland continues to grow as expected and new residents continue to drive at current rates, the transportation system will fail.”— from the report

Geller was receptive to the Seattle’s policy and he acknowledges PBOT must do more. “There remains a long way to go to reach Portland’s goals,” the report states. “If Portland continues to grow as expected and new residents continue to drive at current rates, the transportation system will fail. There is simply not room to add travel lanes without having a devastating impact on the form and character of existing and upcoming development.”

To get there, the reports recommends three approaches: develop stronger design guidelines for all new bike facilities that will attract riders of all ages and abilities, build more of the bike network as quickly as possible, and increase educational and marketing efforts to spread the awareness of cycling.

Given how cost-effective, popular, and beneficial to city life cycling infrastructure is, you’d think Portland could easily quicken the pace to our 25% goal. That might seem like the case from the outside, but within PBOT, staffers would be quick to point out what they see as major structural challenges. In the deflating conclusion to the draft report, PBOT details what they consider as three major challenges facing the future of cycling in Portland.

1) PBOT assumes the dedication of cycling space in existing right-of-way will always lead to a fight:

“Reallocating space in the right-of-way to implement all ages and abilities bikeways represents a change that requires political and public support The future of Portland’s bicycling culture depends on having strong political leadership, an active community of advocates, and an educated public that understands the importance of a multi-modal city and the tradeoffs associated with building out the network of a world-class bicycling city.”

2) PBOT says faster implementation of projects is expensive, takes more staff than they currently have, and is difficult given what they see as a lack of political and public support for bike projects:

“More expensive materials like concrete traffic separators, and sidewalk-level bikeways can be beyond the reach of typical bikeway capital improvement budgets.”

“PBOT is facing a shortage of staff availability to deliver these projects… This has created an immense backlog, making it extremely difficult to deliver projects on time and on budget.”

“There have been numerous cases of bikeway projects getting delayed for years or ending up with substandard facilities because the community and political support to make important tradeoffs was not strong enough.”

3) Changing existing behaviors is difficult, costly, and complicated:

“Convincing the public that bicycling is the safest, most convenient, and fastest option will take time, individualized marketing, and a dramatic change in Portland’s driving culture… it can also be very difficult to reach the public via traditional outreach strategies.”

Perhaps in the final version of this report that we see in front of City Council this fall, PBOT will include a rosier section on opportunities. Our city has the social, civic, and physical foundation to build a world-class cycling network already in place. What PBOT needs is the confidence to go forth and conquer. Hopefully this report helps give it to them.

Download the report on the City’s website (PDF).

— Jonathan Maus: (503) 706-8804, @jonathan_maus on Twitter and jonathan@bikeportland.org

Never miss a story. Sign-up for the daily BP Headlines email.

BikePortland needs your support.

Thanks for reading.

BikePortland has served this community with independent community journalism since 2005. We rely on subscriptions from readers like you to survive. Your financial support is vital in keeping this valuable resource alive and well.

Please subscribe today to strengthen and expand our work.

I’d like to see some of those plots compared to the price of gas

The Gas Buddy site has a charting function shows averages. Select Portland and the 10 year report herehttps://www.gasbuddy.com/Charts

The bikeways chart shows it all: overall size of the bikeway network has only grown about 20% in the past decade. That’s not enough to achieve our goals. And most of the added mileage has been on neighborhood greenways, which are important but are the easy, low-hanging fruit.

Fortunately the second-biggest area of growth has been in protected bikeways, but they’re still a pretty small share of the total.

This is what stagnation looks like.

Honestly, if we added one mile of actually protected bikeway, the increase would be something like 300%. And don’t say parking.

Yes, please, please, pretty please give us REAL protected bikeways.

Also, good callout about the decentralization of bike commuting. Although drive-alone commuting (as a percentage) has decreased a bit over the years, it has actually increased in the more central neighborhoods.

And again, that’s the percentage of people driving alone in those neighborhoods. Remember also that a lot of those neighborhoods have densified significantly in the past decade, which means the absolute number of cars on the roads in those areas has gone up dramatically. No wonder everyone is angry.

(And of course, everyone in a car blames everyone else – including bicyclists – for their misery). Hard to see yourself in the rear-view mirror, as usual.

To combat this, we need to see dramatic improvements in the core neighborhoods because that’s where traffic and congestion are worst. But also in the outer areas where bike traffic is increasing, infrastructure has traditionally been neglected, and people are generally poorer.

In other words, the WHOLE CITY needs a kick in the pants when it comes to improving conditions for bicycling. A strong majority still commute by car: to make this happen politically, you need to convince them that getting more people out of cars is in everyone’s interest – including those in cars.

>>> As many people have left the more bike-friendly core neighborhoods, they aren’t likely to bike as much when faced with longer commute trips and more stressful conditions. <<<

If cyclists moving out of the city core ride more than those they displace, even if they bike less than they did when they lived closer in, it would be a net gain for mode share. (Assuming new residents in the inner core ride the same on average, and with all those new "car-free" apartments, this must be the case, right?)

With the rise of e-bikes, it's hardly a given that bike riders abandon their steeds when they move to more distant locales.

Here’s something interesting. Light, shared transportation options aren’t represented because they didn’t exist when this project started. I presume people who bike-share into work fall into the bike category but I see a number of people scooter-sharing on the commute. Are they planning on adding a category?

>>> What PBOT needs is the confidence to go forth and conquer. Hopefully this report helps give it to them. <<<

This could have been said of the original Portland Bicycle Plan. I don't see any change in our current trajectory on the horizon. 2030 is just 10 years away… that's when we're supposed to have our CO2 emissions firmly under control, and have achieved 25% bike mode share.

Please save these comments for 2025, when they'll be just as relevant.

PBOT needs to get real.

Stop pussyfooting around, stop cowtowing to ODOT, or to car parking interests, and point to the looming threat of climate change to justify the bold steps needed. Screw automobility.

A principled stand works, but we don’t see people much less institutions taking them much anymore.

Trouble is PBOT doesn’t get to make those decisions on their own – the taxpayers funding transportation projects don’t share your line of thinking. It’s as simple as that.

Some of them do, and this is a representative democracy. It would be nice if a majority of our representatives were smart about the effects of their actions and inaction, and worked towards a functioning city rather than for re-election.

“It’s as simple as that.”

Not half that simple, or even like that.

Taxpayers don’t tell PBOT what to think or do. How would that in your view even work? Spine is rare, and pretending that it is the taxpayers fault is just smoke and mirrors, a distraction.

Taxpayers tell PBOT’s commissioner what to do, and she in turn instructs PBOT (or not). It is my hope that PBOT consults with residents when planning and building projects, and would allow them to influence their thinking, but in recent years this seems to be happening less and less.

We can all be the judge of whether this has led to improved outcomes or not.

I think it’s more like voters (not just tax payers) choose a commissioner that aligns with their values and what they want for the city. Not everyone gets the commissioner they voted for and almost no one gets a commissioner that aligns perfectly with all of their values. So any decision a commissioner makes is not going to please everyone.

You say PBOT in recent years seems to be consulting with residents less and less and I wonder what specific examples you’re thinking of. Cause the ones I have for my neighborhood are people complaining about safety improvements (Glisan, Halsey, 102nd) made to roads that have been in the works for a decade and were originally asked for by residents. It’s ridiculous to say that PBOT should be influenced by current residents upset by the changes when they already committed to a plan 10 years earlier. It’s the same with the Lincoln and Harrison diverters. It was already a designated greenway and diverters were already planned if the traffic counts were too high. Consulting with residents about not having diverters years after the plan to make it a greenway was committed too is not an option. The time to consult with residents about that was when they were deciding to make it a greenway.

In both of these examples though obviously not everyone is going to be happy. Also these streets belong to everyone not just the residents along them and the city as a whole has committed to making them safer at the cost of travel time. As far as us being the judge of improved outcomes go I think we should rely on objective data and not peoples feelings. The loudest voices in my neighborhood complaining don’t even believe in traffic counts from PBOT hardly a person I’d want to be making engineering and safety improvement decisions for the roads around me.

“Taxpayers tell PBOT’s commissioner what to do…”

You still haven’t explained the mechanism, the way this works.

How in your mind are these disparate preferences communicated? Who is speaking, who is listening, through what channels does this all occur, and how are disparate views, hopes, priorities reconciled?

This to me sounds like something wspob used to assert. But when pressed he too could not explain it, articulate how it works.

Is this one of those surveys where people respond with their most common form of transportation, and that is the only form tallied?

The majority of people at my work are allowed to work from home up to 2 days a week. They would not be counted in working from home totals. And the people I know who bike to work don’t do so for a majority of their trips, so they aren’t counted either.

Well the numbers are from the census and based on what I found yes the question is just about the majority. So yes it could be misrepresenting a lot of road users that vary their commutes based on work schedules, weather, and season. It seems like with the potential for more riders on fairer days it could be over-representing driving and under-representing other modes in Portland.

I’ve also realized recently that their average commute time makes places like Portland seem a lot worse since we have significantly more people taking slower modes than other cities but they’re all just averaged together. I factored out the additional slower commutes between Portland and Vegas recently and the difference between commute time decreased from 3.6 minutes to 6.4 seconds. Assuming driving would take 2/3rds of the time then the slower mode of transportation.

https://www.census.gov/acs/www/about/why-we-ask-each-question/commuting/

I’m not sure if I really buy this. People usually complain about parking, not about reducing travel lanes. Most of the projects that have gone to shit are because of loss of parking spaces (even if they’re low use parking spaces). Road diets, though, end up going through. People gripe about them, but way less than losing parking.

I think PBOT still does a shit job on make safe biking spaces on our arterials even though the ROW exists without removing parking.

The newest PBOT project where an East-side arterial now has a two-way bike lane with a stop sign in the middle of the bike lane, but the oncoming traffic does not, is so bizarre.

I understand they need political support for projects that remove parking, but I think Chris Warner as interim and now full-time director has done a disappointing job encouraging designs that put safety first.

I commute every day from my home on Mt Tabor to N Williams and Fremont and back. It’s about a 5.5 mile ride that takes half an hour each way. When we bought the house, I considered it on the edge of how far I’d be willing to bike commute. I recently purchased an e-assist bike which I ride about 25% of the time (it certainly helps with the hills around Tabor), and would also theoretically increase the range at which I’d feel comfortable bike commuting, but not everybody has the privilege of being able to afford a nice electric bike.

However, this ~11 mile commute is all on unprotected bike lanes/greenways, with various bits and pieces (Knott, for example) with no bike infrastructure at all. I’m a confident, assertive rider who cycled in London for 3 years and now with 9 years of commuting/cycling in Portland under my belt. Even with all this experience, it can be stressful as hell. My daily commute is often filled with speeding, reckless, distracted drivers and I live _west_ of I-205. East of 205 is another story altogether – so much glass and material in the bike lanes, crazy drivers in extremely large trucks, etc.

How can the city increase bike share when the infrastructure is woefully inadequate, new “greenway” routes are terrible and indirect (see the 20s bikeway) and driver attitudes are straight-up aggressive towards cyclists? I’m not sure they can, but more protected infrastructure would be a start.

I would like to add to the “stressful as hell” comment.

This morning, between 7:30 and 8:30am, I commuted by bike from SW Portland to SE Portland, a distance of ten miles. The following driver behaviors had an impact on my perception of my commute:

– A driver, who was stopped in traffic, decided to pull right, into the bike lane, to get around the stopped traffic. I had slam on my brakes to avoid hitting her car.

– A driver who was stopped at a stop sign, entered the intersection from the left, apparently thinking that I had a stop sign, or not caring that I didn’t b/c she was in an SUV and I would stop for her, which I did, so that she could cross in front of me.

– While I was riding east on SE Clinton (one of our lovely cycling streets!), a driver rolled through a stop sign and fortunately slammed on his brakes as I emerged from behind a parked car. He was talking on his cell phone.

– Again while I was riding east on SE Clinton, a delivery van heading west turned left in front of me. I had to slam on my brakes to avoid hitting him.

And that’s just a typical morning’s commute. It is clear to anyone that the bicycle network, as constructed and as it’s being built, is inadequate to the problem we face: the complete saturation of our streets with automobile traffic, and the near-complete breakdown of driver behavior that enables safe use of the streets for anyone other than drivers.

Someone wrote a great comment a while ago about “bikeways,” and how there are no bikeways in Oregon, meaning dedicated routes for serious bicycle transportation. We have them for automobiles. Is it possible that we will need something like an Interstate Highway Project for bikes if we ever hope to meet the 25% goal?

This is so disappointing, and it appears is missing the forest for the trees. They are focused on and tallying up miles or linear of bikeways, which is a fine way to start to build bike infrastructure. But PBOT has always taken an opportunistic, not holistic, approach to building bike infrastructure: they build one segment at a time. The problem is, a network is only as good as its weakest link. While many stretches of greenway are low-stress, the vast majority of connections across busy streets remain unaddressed and connitions to/from the greenways are often non-existing or dangerous (see 37th/Prescott or Going/MLK and MANY more). A protected bike lane is great when you are on it, but it does not serve the network if it lacks connections or contains pinch points/dangerous spots. PBOT bends over to be practical and find compromise, but that mindset dooms them to failure for creating a high-functioning, complete network. PBOT needs to put safety first and convenience/directness for the bike route second. They need to push back hard against drivers who worry about inconvenience or lost parking. I feel so disheartened by this report: the leadership within PBOT is so paltry and lame compared to what it was even 10 years ago and the mayor/council are equally lame. I do not see anyone proposing a comprehensive to get anywhere. Without a clear vision and defined priorities, conversations about equity will spiral around and around and nothing will get done.

What he said.

The official City position should be this: If the street parking is important, that means it has value and should be metered and charged by the hour. If the presence of meters clears out the curbside parking, then it would be better utilized as a bikeway. This would have resolved the issues on the 20s bikeway.

Streets are valuable. We shouldn’t be giving that space away for private property storage.

NW Portland saw a decrease in on-street permits issued to residents from 2017 to 2018, an 11% decrease. During that time, the cost of a permit went from $60 per year to something like $175. Then it multiplied with additional vehicles, I cant recall the exact number, but it was going to be around $500 for the year for two permits. Cheaper than a garage in a building, but still expensive enough to get me to sell a car and not replace it. The pot was sweetened with credits for non-car transportation type stuff, like a biketown membership and a hop card and stuff.

The price of a permit went up again this year, so I would expect the number of permits to go down a bit more.

Here’s a source and a neat read for the decrease in parking permits sold in NW: https://www.portlandoregon.gov/transportation/article/730545

I’ve complained repeatedly that Portland provides on-street parking directly adjacent to corners & crosswalks, when is illegal everywhere else in Oregon. If those spaces are so valuable, Portland should be charging a premium on it, like $20/hour or more for corner/crosswalk parking. That money can then be set aside for the day that someone is killed as a result of the reduced visibility, and their family sues the city for allowing it.

Just designate the last 20ft of the block just before the stop sign as a loading/taxi zone. This would keep them clear more often, and would hopefully stop those folks from just standing in the travel lane/bike lane.

Bike corrals.

PBOT have recognized that daylighting needs to take place https://www.portlandoregon.gov/transportation/index.cfm?&a=697586

Their solution is milquetoast at best as daylighting will only take place during a prior project or from public complaint.

Build it and they will come seems to be working, at least for neighborhood greenways. My questions about that data come down to whether this comes down to preference and if this is a good thing.

Among preferences, there’s probably a mix of people who prefer the quieter streets to busy bikeways, while others are taking advantage of more occasions to use their neighborhood as the east side gets denser. The latter is not exactly my style, but does have much more potential in the way of public health, the environment, and land use. It’s a far larger audience than the car commuters people keep trying to chip away at.

To me the 2009 vs 2019 bikeway map looks like a difference of 1 zoom level on Google Maps.

On one map you have all the designated bicycle streets which include greenways. This in the network of the brave who don’t mind riding with cars. https://goo.gl/maps/1iEenvfX42v44p4w8 (5000 ft scale with Bicycling toggled on)

On the next zoom level you have only the streets with bicycle lanes. This is the network of the interested but concerned crowd that doesn’t want to bike where cars are going to kill them. https://goo.gl/maps/zjenLr13okUyyVtw6 (1 mi scale)

The latter is the real progress we’re making towards all-ages bikeways, and it’s dismal.

I love greenways until drivers discover them, and want to be able to define a greenway as a street that has frequent diversion – cars can’t go more than a few blocks. I hate bike lanes, because they only exist where traffic speeds and volume are too high, they are used as turn lanes, they collect every piece of junk that falls on the road, and they are far too rarely swept.

The thing that stands out to me on the ‘How Portlanders Got to Work’ plot is the 87% of drivers who are commuting alone. I know that many people only have the practical option to drive, but its just such a gross inefficiency in space (plus energy, pollution, etc) to have almost everyone driving a vehicle alone with three other empty seats, or another five to seven empty seats for SUVs. Why are there no goals or projects to reduce the fraction of single occupant vehicle commutes and turn them into multi occupant commutes. Everyone pays for this inefficiency, by way of billions spent on unnecessary demand inducing mega projects.

Why not use the congestion tolling stations to charge only SOV trips during commute times, then credit MOV trips with the tolls (TNCs excluded). A carrot plus stick system could run a tab, adding or subtracting each time you pass the station. This removes the perception that the tolling is a war on all car commuters, but instead a war on inefficiency.

The popularity of Uber and Lyft proved many people are willing to ride with another person, and its only become much easier to carpool now with waze carpool. Medium to large sized companies that refuse to have an in-house carpool program to match employees should be charged a head count impact fee for their contribution to congestion.

I have an idea. Our grid is already divided up into main streets where cars are prioritized and neighborhood streets that are exclusively (or nearly exclusively) residential. Just pull out the map and pick a neighborhood, and it’s easy to find large rectangles of neighborhood streets. Think Ladd’s Addition (Hawthorne to Division, 12th to 20th) or Cully (Fremont to Prescott, Cully to 82nd) or Woodlawn (Ainsworth to Dekum, MLK to 15th) or anywhere – the boundaries are generally obvious. Make it illegal to cut-through any neighborhood street in a car. To drive through a neighborhood street, one must put on their flashers and drive 10mph or less. No big deal, because you can only go a few hundred yards at most. People, not vehicles, always have the right of way in the neighborhood street. Install a cross of diverters if people cheat too much. (though I wonder if the cut-through law, by itself, would help a ton anyway – everyone uses apps nowadays and if the apps weren’t allowed to violate the cut-through law…). On the main streets, 20mph speed limit. If this plan is too bold to roll out all at once, start with a few neighborhoods and see what happens. I suspect that people who live there will LOVE being able to feel safe in the streets again. Driving commute times go up a tiny bit? Ride a bike or take the dern bus for crying out loud. I have more ideas too. Or what’s your idea? A real idea that might actually achieve real progress.

Good luck to you on getting diverters everywhere. Those of us who have been working to get them rarely get them _anywhere_.

Well, civil disobedience.

Three am, or ten am, whatever works for you.

Years ago my commute was 24 miles round trip. My car averaged about 24 miles per gallon. It pained me that each day of driving was the equivalent of setting a gallon-sized milk jug of gasoline on fire for my own convenience. I quit driving and eventually sold the car. Biking took five minutes more time than driving each way. The fragments in bike network were the biggest obstacle. Complete the network (looking at SW, outer NE, & lower SE), safer crossings, and provide separation. Only then will the interested but concerned at the limits of town be encouraged.

Earlier this week I happened to listen to a Toyota ad where they were touting that their designers had accounted for accommodating a group of four PLUS weekend luggage in the design of the SUV. And, as I was passing all this empty space being used on my commute home, I put some of the blame on the vehicle manufacturers AND the consumers. Because they are designing and purchasing vehicles for the 10% of the time the vehicle is used, rather than designing and building vehicles for the 90% use case.

“Weekend” luggage for 4 should easily fit in a compact car’s trunk. What are these people bringing on their weekend trips?

The luggage expands to fill the space. Punk or bougie, same deal.

Wait a minute. The 2019 bikeway map still shows SE 26th as a bike lane where it intersects Powell. That lane WAS REMOVED BY PBOT earlier this year. What other conflation errors exist?

SW Capitol Hwy from Barbur to Multnomah Village is drawn in despite not having broken ground yet. Also SW 4th and I’m guessing most of CCIM. All of the double-lines on the map are “planned” bikeways i.e. thoughts and prayers.

I agree with all the other commenters that investing in *good* bike infrastructure at a faster pace would be an important first step to get us to the 2030 vision, but I think it is not sufficient. While safety often plays a role, convenience of driving is equally important, and currently, it is still way to easy and convenient to drive to work in Portland.

Case in point: I live in inner NE. From there, you can reach downtown via a fairly safe bike network. Tillamook is great and gets you to Moda Center, and from there, you can take the car-free waterfront paths. But biking is not the fastest way to get downtown, requires thinking about clothes, messes up a hairstyle, is (at least initially) physically exhausting, and not as pleasant as sitting in a car on hot summer days or cold, rainy winter days. So most people in my neighborhood drive to work, not because the bike infrastructure for their commute is bad, but because driving is so much easier.

My take on the long-standing infrastructure debate is that even if we implemented 100% of the planned bike infrastructure, bike commuting rates would not tick up beyond about 10 percent, maybe. We’ve exhausted the pool of enthusiastic riders, and the next group of people might be concerned about safety, but they are equally concerned about the inconvenience of biking relative to driving. So making our streets safer just won’t bring the numbers further up.

If we really wanted to transform the way people get to work, then we would need to make driving to work much, much more unpleasant, by eliminating parking, tolling the downtown area, putting lots of barriers into roads, and closing off whole blocks in the downtown area. And that, my friends, would just piss off so many people off, it will not happen.

Congestion pricing, no free parking and price it variably based on demand. All earnings above cost to be used by active transportation and transit projects/maintenance. Stick followed by well fertilized carrots.

This comment almost has my vote for Comment of the Week. I disagree with the “It will never happen” sentiment, b/c I think it will happen if things get bad enough. But you really hit the nail on the head with your diagnosis of why people won’t get on a bike: it’s just too darned easy and pleasant to drive a car. Ease back into that comfy seat, put your coffee in the cupholder and bring up some nice music on the stereo, wiggle your small toe and feel the pull of 180 horses – not to mention the steel cage and airbags to help you feel safe. Also you have an entire network of infrastructure to ease your journey with smooth and fast roads, and parking for your chariot within an easy walk of your workplace – sometimes even within the same building. If anyone ever questions your need to drive alone, you can bring up a widely accepted argument about needing to keep a schedule that allows you to pick up your kids from school and take them to soccer practice (or board your dog, or take your spouse to the doctor). The whole arrangement is really bullet-proof.

Re changing existing behavior:

PBOT and all other public agencies should redirect all money regarding “see and be seen” campaigns to “5 miles in 25 minutes” to both entice people to get out of their cars and set a standard for bicycle infrastructure. If someone bikes at an average of 15 mph, plus time for stops, they should be able to travel 5 miles in roughly 25 minutes.

Also, the most influential way to change behavior is for people to see others doing it. The green way strategy reduces visibility of people using bikes, except for the cars abusing greenways. Protected bikeways on major arterials is key to changing mode share.

Its almost as if spending a decade building out a robust network of parallel routes that don’t directly serve businesses and services, don’t provide safe and signaled crossings of major intersections, and don’t continue to separate bikes from car traffic as the surrounding land use changes was not the right place to prioritize investment.

Yeah, but underdesigned greenways that mostly leave out diversion & signalized crossings of major streets are cheap & unobtrusive. So, Portland politicians didn’t have to do anything politically difficult, like raising more money or upsetting comfortable car commuters! Avoiding political difficulty has to count for something, right?

/sarcasm

Serious comment – personally, I don’t think that the prioritization of the investment (both $ and political capital) is the primary problem. The problem is the amount of the investment.

If Portland had gone ahead and rapidly built out and retrofitted a network of REAL greenways (with diversion every 5-10 blocks, signalized crossings of all major intersections, etc.) and finished it by say 2015, and only THEN moved on to building 20 miles of really good, protected bike lanes with protected infrastructure per year, I’d be OK with that prioritization. Conversely, if Portland had been building 1 miles of protected bike lane per year instead of 10 miles of weak, underdesigned greenways per year, that prioritization wouldn’t have saved the fact that a few miles of good protected bike lanes spread around the city would be far too little.

The biggest problem is that the amount of money, political capital, and street space that Portland’s past decade of politicians have been willing to put into bike infrastructure is woefully insufficient to meet the City’s own goals for climate and transportation.

Comment of the week.

The large drop in bike mode share in Kerns, Hosford Abernethy, and Buckman (neighborhoods that previously had some of the highest bike mode share) illustrates how gentrification is pricing people who bike out. Given the delayed effects of gentrification it’s a near certainty that more people who bike (and bus) will be priced out.

Portland needs more density but we don’t need more high-end market rate housing and its associated gentrification.

Where did you find data on changing mode share by neighborhood?

The map above. (Some of these close in neighbords previously had mode share very close to 20%)

Ok, yes, I see. They’re not really neighborhoods, but it looks like HAND stayed the same, and “Buckman” went down, though it includes most or all of CEID. I don’t think the conclusions you drew about causation are supportable.

there was an unambiguously sharp drop in mode share in close-in SE neighborhoods that historically have had the highest mode share in the city (around 20%)?

my explanation is that the close-in SE has one of the highest percentages of renters (~80% in buckman and ~60% in HAND) and that the rapid rise in rents has result in *displacement* of longtime residents who bike.

what’s your explanation? that all of the bike riders are homeowners homeowners?

PS: The new census ACS update is due in a few days. Doubt it will be good news for cycling.

I don’t think HAND’s share of renters has changed dramatically over the past decade. It’s hard for me to decode those maps into any kind of meaningful numbers. Generally speaking, it wouldn’t surprise me if there is a newer, younger cohort of residents that bikes less than the corresponding cohort is 2009, perhaps because of the arrival of Uber and Lyft.

I am at a disadvantage because I don’t have an explanation ready to go when the data arrives (which, for me, has to be more than big blocks of color on a low-res map without much context).

“I don’t think HAND’s share of renters has changed dramatically over the past decade.”

Are people who move into apartments from out of state more likely to bike than long-term residents?

I have no way of answering that, and don’t have the data to know if it’s even relevant (though I suspect it is).

Those maps are a bit hard to read just because it’s all green, but it looks to me like those neighborhoods showed a small decline in mode share. Meanwhile the neighborhoods in close in North Portland and Northeast around Williams/Alberta had large increases, as did numerous wealthy neighborhoods on the west side + Sellwood/Westmoreland/Eastmoreland. Looking just at the map it is very hard for me to draw a straight line between changes in incomes and changes in mode shares,

do you have a hard time drawing a “straight line” between higher rents and tenants being priced out?

given your laissez faire track record here…i suppose you do.

I have no doubt that Williams/Alberta area has gentrified dramatically–many low income folks have been priced out. This is particularly a problem for African American families who can’t afford rent anymore and are being pushed out. The inner southeast neighborhoods have experienced some gentrification as well, though I’d say to a lesser extent. So I don’t dispute the relationship between higher rents and lower income people being pushed out.

What I do dispute is the relationship between this phenomenon and bike mode share. On the maps I see some areas (inner Southeast) that have gentrified but bike mode share has gone down. Others have gentrified (Williams/inner Northeast/some areas near St. Johns arguably) but mode share has gone up. Some areas have stayed rich and seen increases in mode share (Sellwood, a lot of areas on the West Side). So it’s undoubtably true that there has been gentrification. What’s less clear to me is how this is related to cycling.

Work from home went up, driving alone went up, walking went up, biking stayed flat, and transit went up. My question is this: what about Lyft, scooters, biketown? Are they lumped into these categories? I also wonder how realistic it is to have a goal of 25% bike mode split in 10 years? I’m all for big goals but if the mode split of driving alone is 56.7% then you have to actually dissuade driving to make people switch, which we know PBOT and ODOT have not done.

While far from ideal or world-class there have been many welcome improvements (and two new bridges!) in the bike infrastructure in the last ten years and I find it much easier to find a decent route to various destinations. The report does not seem to dig in to analyzing why there has only been a 0.5% increase in bicycling mode share especially given the improvements in infrastructure, more congestion for cars, and increased e-bike ownership. What were the expectations for this timepoint? Is the large increase supposed to come when all of the planned infrastructure is in place?

If we don’t know why a greater percentage of people are not bicycling despite the better network how can we achieve the goal?

I don’t know the cause but for my two cents it seems like safety may be a big reason. The new valuable infrastructure is undermined by lack of enforcement of no right on red, speed limits, stopping at stop signs and red lights.

At a recent lunch with prior PBOT bike folk, I asked about biggest impediment to progress. Universally the answer was PDX governance system of many council reps. The nitpicky differences are the enemy of good.

Let’s reframe this like others are this week: Climate change is the biggest existensial threat to humanity. In 12 years, damage will be done that we cannot reverse with warming >2 degrees and all the disaster that comes with it baked in.

It’s time to treat this as the threat it is. Now, go back up and reread these comments. Discussion like this will get us nowhere. Look at the 3 excuses from PBOT. Discusssion like that will get us nowhere.

It is time to be bold. Some will be angry. But placing their positions along side those of our dying planet make the prioritization clear.

Be bold.

Could it simply be that most people don’t want to ride their bicycles in the rain for 8 months of the year? Keep throwing money at it, Portland…