(Photos: Caleb Diehl)

Scott Dalton’s wife was walking home from Safeway in December 2017 when a person driving a car struck and killed her.

“She was in the crosswalk,” he says. “One car stopped and the other car didn’t.”

Dalton, a retired journalist, has lived in east Portland near 117th Avenue, for twenty years. In that time he’s seen a steady stream of people die while walking or biking. This year alone, five people have been killed while walking in the neighborhoods east of I-205.

Dalton showed up at the Portland Bureau of Transportation’s open house Wednesday night hopeful that a slate of new projects will finally bring change to the neighborhood. In the past four years, PBOT has pumped $255 million into its “East Portland in Motion” projects, many of which will break ground in early 2019.

“There are sidewalks and bike lanes that are narrow. There are long distances between crossings. It’s not working and we need to rebalance that.”

— April Bertelsen, PBOT project manager referring to 122nd Avenue

Home to 165,000 people, east Portland stretches from 82nd Avenue out to city limits at 162nd. Much of it developed during the highway building boom of the car-crazed 1950s and 1960s. That inspired a sprawling grid of strip malls, car dealerships and fast food restaurants. In the decades after that, gentrification and displacement pushed many people out from inner northeast.

More of these Portlanders drive to work compared to commuters in the city as a whole. The alternatives are slim — a struggle through the network of five-lane, high-speed roads on foot, by bike or on unreliable buses. Bike lanes appear out of thin air only to morph into right turn lanes a couple blocks later. Sidewalks end without warning. It all adds up to a death toll everyone says they want to address; but so far the needle hasn’t moved.

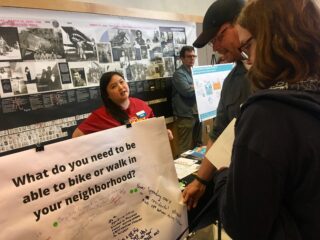

The open house was held at Midland Library just off 122nd Avenue, one of the busiest — and notoriously unsafe – streets in the area. PBOT showcased a handful of new projects and collected feedback. The reception from the large turnout seemed mostly positive.

Concerns centered around the cost of the projects, whether the construction would affect their daily commutes and balancing out different modes. Walking safety seemed to be a big issue — specifically the fact that safe crossings along major streets are too spread out.

The big center of attention was the East Glisan Street Update project. A large group of people clustered around PBOT Project Manager Timur Ender. The project includes eight new pedestrian crossings and buffered bike lanes that will take the place of lanes currently used to park cars. Residents had concerns about how the changes would the flow of auto traffic.

A project to tame outer Division, a notoriously dangerous stretch from 82nd to 174th ave, will be big on the list. It’s one of the deadliest streets in Portland. According to stats PBOT shared at the event, in the past decade 13 people were killed and 117 were seriously injured on outer Division.

Advertisement

The central feature of that project is a raised median. The speed limit will drop from 35 to 30 mph. Bike lanes will be set off from the road with a buffer. The median and buffer zones will shorten crossing distances.

Another major project will overhaul 122nd, a high-speed, five-lane corridor that spans six miles from SE Foster to NE Marine Drive. The bike lanes are narrow and an arm’s length away from speeding cars. Crossings are few and far between. Buses are often delayed.

There’s about $2 million set aside for this project for now, and the planners are looking for other funding sources. They’re taking input from community members on how to spend the money.

“There are sidewalks and bike lanes that are narrow. There are long distances between crossings,” says April Bertelsen, the project manager for 122nd. “It’s not working and we need to rebalance that.”

Another street on the high crash network, NE 102nd ave, will get more crossings and fewer lanes. The current recommended design knocks the five standard lanes down to three, with pedestrian islands in the center.

Linking those two major north-south corridors will be a revamped couplet of one-way streets, Halsey-Weidler. Those streets will get rapid flashing beacons, wider bike lanes and more lights and trees. The idea is to create a revitalized “main street” where people can easily walk to local businesses.

“Drivers need to change their habits, which they’re not too big on.”

— Scott Dalton, local resident

PBOT is also planning more than 30 miles of greenways in East Portland. One new neighborhood greenway will wind through Knott, Russell and Sacramento streets.

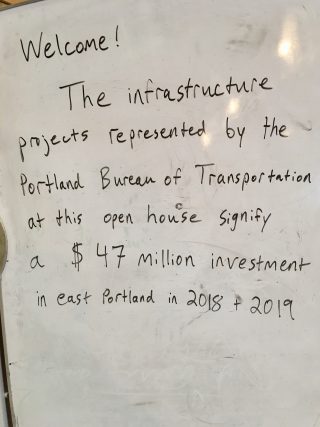

About half of the funding ($130 million) already allocated for these new projects will go to outer SE Powell Blvd. Another $47 million will fund various projects scattered around east Portland from Foster to Parkrose — a fact PBOT was happy to announce on a hand-written sign at the entrance to last night’s open house.

Much of the funding comes from the Fixing our Streets program, a measure voters approved in 2016 to generate $64 million in funding over four years. Other money comes from System Development Charges (SDCs), taxes on new development in the area. And some of it’s up in the air—it could come from grants or HB 2017, the recent $5.3 billion statewide transportation package.

Dalton was impressed. “PBOT really knows what they’re talking about,” he says. But he added, “we won’t know until we see it.”

He’s worried people who are used to speeding through the neighborhood won’t change their behavior, no matter how much infrastructure goes in. “Drivers need to change their habits,” he says, “which they’re not too big on.”

Hopefully, thoughtfully engineered infrastructure will change those habits for them.

These are just the highlights of East Portland in Motion. You can view the full list of projects here

PBOT will hold another open house, where you can comment on the projects, on June 5, 6:00-8:00pm, at Rosewood Initiative (16126 SE Stark St, Portland, OR 97233).

(CORRECTION: This story initial published the last name of Scott Dalton as “Palton”. That was a mistake. We regret the error.)

— Caleb Diehl, @calebsdiehl on Twitter.

Never miss a story. Sign-up for the daily BP Headlines email.

BikePortland needs your support.

Thanks for reading.

BikePortland has served this community with independent community journalism since 2005. We rely on subscriptions from readers like you to survive. Your financial support is vital in keeping this valuable resource alive and well.

Please subscribe today to strengthen and expand our work.

I appreciated the PBOT staff who were on the front line explaining to area residents why it makes sense to reduce travel lanes in favor of protected bike lanes. It was also great to see residents and community partners on the bike ride to see where improvements will be made.

Hi Jillian,

Just wanted to say thanks for commenting. I appreciate it!

Caleb is a good writer.

It seems quite simple: if you want people to not be killed crossing the street, you can’t have two lanes of traffic in each direction. That design is inherently dangerous, and is not suitable, in my opinion, for urban areas (unless you are willing to build signalized crossings at every intersection, as we have downtown).

We need an alternative design for bona fide arterials where the traffic volume is too high for one lane each direction. Think some of Powell, or most of 82nd or Cesar Chavez/39th, etc.

How about narrowing the lanes in the cross walk and for the 20 feet before the crosswalk, to install pedestrian refuge islands between each lane, with substantial concrete barriers between the ped on the island and oncoming traffic. Drivers slow down when they have to thread through a narrow spot. Extending the narrow lanes and ped island for 20 feet before the crosswalk helps with visibility. Wide emergency vehicles can still get through using the center turn lane.

That sounds like a call for a large number of pedestrian overpasses–or outgrowing the 1955-vintage concern with speed of motor vehicle traffic. Sorry, but no junkie gets clean by having bigger veins transplanted into their arms.

“…thoughtfully engineered infrastructure…”

PBOT’s next director must be an engineer.

Which Leah most definitely was not.

I’ve heard this critique several times and it simply doesn’t hold water. Managing a department of skilled engineers is different from a being an engineer first and foremost. Groupthink and organizational opposition to the phenomenon is one of the rallying cries heard here against the Oregon Department of Transportation. Treat was aware of the fiscal constraints PBOT butted against and yet still ushered in 20 miles per hour speed limit to the state legislation as well as an incredible addition of marked crosswalks within the city’s inventory during her time. That is not insignificant given the decades of city-wide inertia prior to her tenure. If PBOT can find a director that is both an engineer and effective at managing a city bureau then great, but it is not an axiom of whether someone will succeed as director or not.

I’m glad I stopped by this open house – the chance to get to speak to project managers and coordinators in person always brings insight. For instance, I was speaking to the folks at the 130’s greenway table, asking why I kept hearing the project was about to enter construction only to be delayed again and again (this time construction is supposed to start September 2019). They explained that there was some hold-up due to projects simultaneously being worked on like the Safety Action Plan for Outer Division as well as the Division Transit Project, so having to coordinate across teams with changing plans and waiting for things to be finalized caused a delay. Makes sense to me, makes me feel less frustrated about the delay because now I understand it. They also seemed to think that no one cares about hearing why delays occur, even though that is what I was asking about. I think that if the city is communicating what projects are supposed to happen, they would do well to communicate why they were not able to stick to that schedule because people are waiting on these projects to happen!

I think this communication would also help hold them accountable!

Most of these projects, except Powell, were funded between 2010 and 2013. This open house should have occurred 5-7 years ago. As for the projects themselves, let not get carried away here – there’s still plenty of time to delay them for another 5-10 years, so the PBOT can redesign them for the 5th time, reducing the funds actually available to build anything. NE Cully was delayed by 15 years after the city got state and federal funding; by the time they were ready to build, inflation had eaten a third of the funding.

I’ll be extremely grateful for these projects, especially if the greenways that stretch into the 160s actually deter or discourage cars being driven through them.

I hope the city has learned from its past greenways that sharrows and cute signs are not enough to transform a street into a greenway. Robust diversion will be even more necessary on these streets than they are for the more central greenways, since the roads are typically wider and there’s a higher percentage of menacingly large trucks and SUVs.