(Photos © J. Maus)

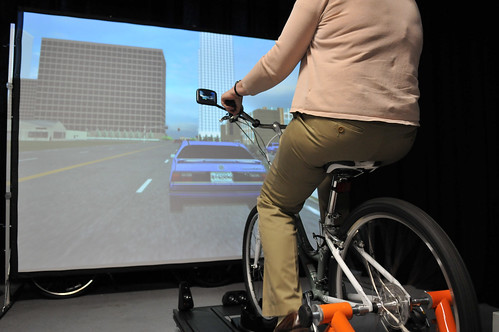

A research laboratory at Oregon State University in Corvallis is the first in the nation to integrate an advanced driving simulator with a bicycling simulator. When the two are connected, researchers can collect real-time data on how vehicle operators react in an extremely realistic, three-dimensional roadway environment.

Think about that for a minute.

“This is the only lab in the country where you can run a live subject on a bicycle and a live subject in a vehicle and get real time user performance response simultaneously.”

— David Hurwitz, Ph.D.

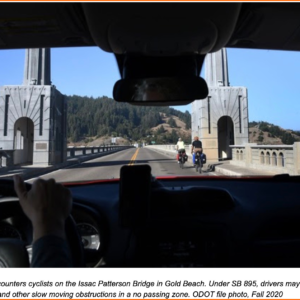

Imagine the possibilities of researchers being able to do everything from testing how road users react to each other, how different road designs work (before they get built), how long a driver’s eyes leave the road when they change a CD — all with subjects on both sides of the windshield navigating through real-world conditions.

Yesterday I got the chance to visit the lab and learn more about this exciting project.

The lab is housed in Oregon State’s School of Civil and Construction Engineering and it’s run by the research team of David Hurwitz, Ph.D., and Karen Dixon, Ph.D..

Dixon, whose background is in highway design said she initially ordered a driving simulator for traditional research purposes (there are about 40 of them around the country). “Then it occurred to us,” she said, “that, living in Oregon, it’s pretty short-sighted if we don’t do something to also capture our vulnerable road users on bicycles.”

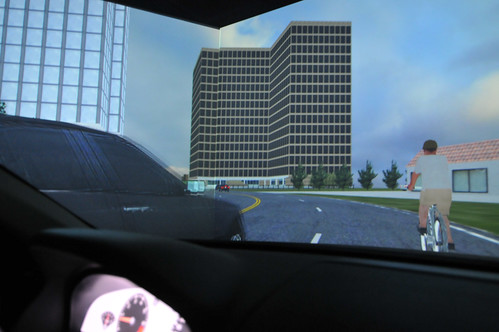

Today, their lab consists of two simulator stations. A Ford Focus sedan sits on a motion-based platform that’s enveloped by three large screens (one in front, two on the sides). There’s also a screen behind the car and LCD displays in both side mirrors and the rear-view mirror. The bicycle simulator station has only been up and running for about six weeks and currently has just one screen (although it too can be placed on the same, motion platform that the car uses).

“In my intro to highway design classes, they design projects on a flat piece of paper…That’s the way we’ve done it for many many years and I think it’s time to change that.”

— Karen Dixon, Ph.D.

There’s only one other lab in the U.S. that has a bicycling simulator; but they’re not focused on transportation engineering or safety research. “This is the only lab in the country,” says Dr. Hurwitz “where you can run a live subject on a bicycle and a live subject in a vehicle and get real time user performance response simultaneously.”

As I sunk into the driver’s seat of the car, I was immediately impressed. It subtly dips and sways just like the real thing. When I glanced out the window, buildings and trees blurred by. Stereo speakers mimicked the sound of the engines and passing cars. When I pulled into a KFC drive-through, I felt the small bumps of the driveway and then circumnavigated the building. It truly was a realistic 3-D environment.

Check out this short video which I took from the driver’s seat:

As I drove around the virtual streets, graduate research assistant Lacy Brown suddenly pedaled up behind me. I first saw the bike in the rear view mirror. Then Brown passed me and was pedaling in the lane right in front of me. Situations like this can give the lab clues about things like; how much space a driver feels they need to give someone on a bike, where a bike operator prefers to position themselves on the road, how blind spots impact visibility, and much more.

“Because there’s a screen behind the car, you can see the cyclist approaching,” says Hurwitz, “With our onboard cameras and eye-tracking systems, we can determine if the driver actually looks in those places or not.”

The epidemic of distracted driving is also something Hurwitz is eager to do more research on. “We can test how long someone’s glance leaves the road when they do various tasks. We know from previous research that there’s a magic threshold of two seconds — any longer than that and the risk of crashing goes up substantively.”

Dixon’s inspiration for the cycling simulator also speaks to another valuable example of potential research. Dixon recalls that she once pulled up to a red light in her car and noticed someone on a bike next to her leaning over. “I thought the heck are they doing. Then I realized they were just trying to see the traffic signal but the louvers were positioned for people in cars. The signal was screened from the view of people in the bike lane.”

PBOT engineers face this exact problem with the cycle track on SW Broadway. Analysis shows that there’s a high rate of non-compliance with traffic signals by people using the cycle track. As a PSU transportation expert told us last year, the culprit likely has something to do with how difficult the light is to see from the curbside bikeway.

If you think research like this is something that we can’t afford in today’s budget climate; consider this. Dixon points out that one of the major benefits of the simulators is that transportation planners and engineers can test their designs before they put them in.

“It’s so expensive to build something, wait and observe it, and then decide if you did it right or not. If you can do it in a simulated environment, you can weed out a lot of issues.”

Dixon teaches a highway design class, so she clearly understands how putting students behind the wheel — and the handlebars — to test their designs can be a game-changer.

“In my intro to highway design classes, they design projects on a flat piece of paper. They’re supposed to be able to visualize what that looks like. That’s the way we’ve done it for many many years and I think it’s time to change that. You can make something as 3-D as you want on a computer screen, but you can’t get them to understand all the different nuances of the environment.”

While the research project ideas are exciting and limitless, Dixon and Hurwitz say their main focus is safety. Or, as Hurwitz puts it, “To better understand the interaction between vehicle operators, the built environment, the vehicle itself.”

I was impressed not just by the high-tech lab but by Dixon’s open-minded and enthusiastic approach to her work. She’s eager for partnerships with advocacy groups and she’d love to hear ideas from the community about how to get the most out of the bicycle simulator.

Imagine if we had this type of system set up at the DMV?

What if we could run-through various design options for, let’s say, the N Williams Avenue project?

Stay tuned for what is sure to be some important and exciting transportation research from this lab.

—

Links:

– Hurwitz Research Program

– OSU Bicycling Simulator

Thanks for reading.

BikePortland has served this community with independent community journalism since 2005. We rely on subscriptions from readers like you to survive. Your financial support is vital in keeping this valuable resource alive and well.

Please subscribe today to strengthen and expand our work.

Cool concept but looks like the simulator is lacking significantly when it comes to response time. Numerous times, the steering wheel turned and then the simulated view slowly caught up (I’m assuming this is why you almost rear ended the cyclist). Whoever is manufacturing the simulators should team up with some modern video game designers.

If the simulation is flawed, it could really hurt the research.

Also, there should be more weapon pick-ups.

As someone who has used the simulator. I don’t think it’s as lacking as you think. FWIW, the motion system was developed by a company that also makes them for the US military to train troops to operate vehicles in the battlefield.

As for turning it into a game. Dr. Dixon is open to this as a way to promote its use among kids.

They need more live cyclists for realistic interactions.

Promote as: “Grand Theft Fixie: Portland”.

It really does look like the steering control/response is out of sync with reality. But otherwise the realism is pretty awesome. What a great piece of technology.

Yeah, but this was a Ford.

Cool idea, but of course people are going to be on their best, attentive behavior when they know they’re being observed. How they act here and how they act at a real stop sign when the cyclist got there first may be two different things. One thing that might be particularly useful would be to require all those enrolled in Drivers Ed to spend some minimum time, like two hours, on the bike in this simulation. The purpose being so everyone gets a taste of what it’s like on the other side before they get behind a real steering wheel.

“but of course people are going to be on their best, attentive behavior when they know they’re being observed.”

There should be ways to design studies to address that. For example, if you want to test how safe drivers are when using “hands free” cellphones, tell them that you are testing the hands free device, or that you will be asking them some questions about the conversation they have on the hands free device. In other words, if you want to test their driving, tell them the study is about something other than their driving.

I appreciate that they are trying.

Sim input feedback loop is far too slow.

The urban environment is unrealistic.

By that I mean watch the video set which is set in a “dense” urban environment. The sight lines represented are far too optimistic. This much cleared viewscape around buildings and trees exists primarily in rural farm land. There needs to be more trees, more signs, more pedestrians, more parallel parked autos, more large trucks.

Kudos to the auto driving participant for not following the law and avoiding simulated police. For the sake of the cyclist participant simulated auto drivers should break traffic laws at rates if 1%~5% when the opportunity presents: right hooks, passing too close, rolling stop signs, aggressive and menacing drivers in narrow lanes. These are all things that scare cyclists and can be quite deadly.

My suggestions are not outside the realm of current computer abilities nor has it been for several years.

What a lucky guy you are Jonathan. The test actually seems like a ton of fun. Go Nerds!