How do you accurately gauge what type of bicycle infrastructure treatments work best? Crash data alone is far from robust enough to get a clear picture. Video evidence can be helpful, but it’s a pain to gather and it’s not easy to create the controlled environments necessary for scientific research when you rely on real-life traffic.

That’s where an innovative lab at Oregon State University in Corvallis comes in. Researchers there have a bicycle simulator that mimics traffic conditions (which you might recall from a story we shared back in 2011). And since it’s in a lab, riders can be tracked with all sorts of helpful technology to better understand how they react to different situations.

A new study by Logan Scott-Deeter, David Hurwitz, Brendan Russo, Edward Smaglik and Sirisha Kothuri published in Accident Analysis & Prevention (Elsevier, January 2023), used the simulator to compare three popular design treatments aimed at making bicycling safer. The research team (from Oregon State, Northern Arizona, and Portland State universities) wanted to know how riders responded when they approached a mixing zone, a bicycle signal, and a bike box. They tracked stress levels, eye movements, and riding behaviors of 40 study participants to see which design is best suited to avoid collisions.

If you ride in Portland, all three of these designs should be familiar to you. A mixing zone is where the bike lane drops just prior to an intersection and is replaced by sharrows and other lane markings. The idea is the markings will convey to bicycle riders they should expect drivers to “mix” with them as they cross over the lane to make a right turn. Bicycle signals have become relatively common in Portland in recent years. This is where a bicycle rider will have their very own signal phase to cross an intersection. And the bike box has been a standard treatment in Portland since 2008 or so. These are typically painted green and connect to bike lanes to form a large box at the very front of an intersection so bicycle riders can get ahead of drivers and become more visible.

To run the tests, the riders pedaled a stationary bike in front of large, panoramic screens and responded to 24 different traffic scenarios. To assess how each rider and design performed, researchers used a survey, tracked eye movements to quantify how long riders took to assess possible risks, measured stress levels, and marked down the path each rider took.

A majority of the riders identified as female and there was a wide mix of experience levels. 42% of them rode just one time per week or less.

The overall winner, when all factors where taken into consideration, was the bike box. Here are some key takeaways:

Mixing Zone

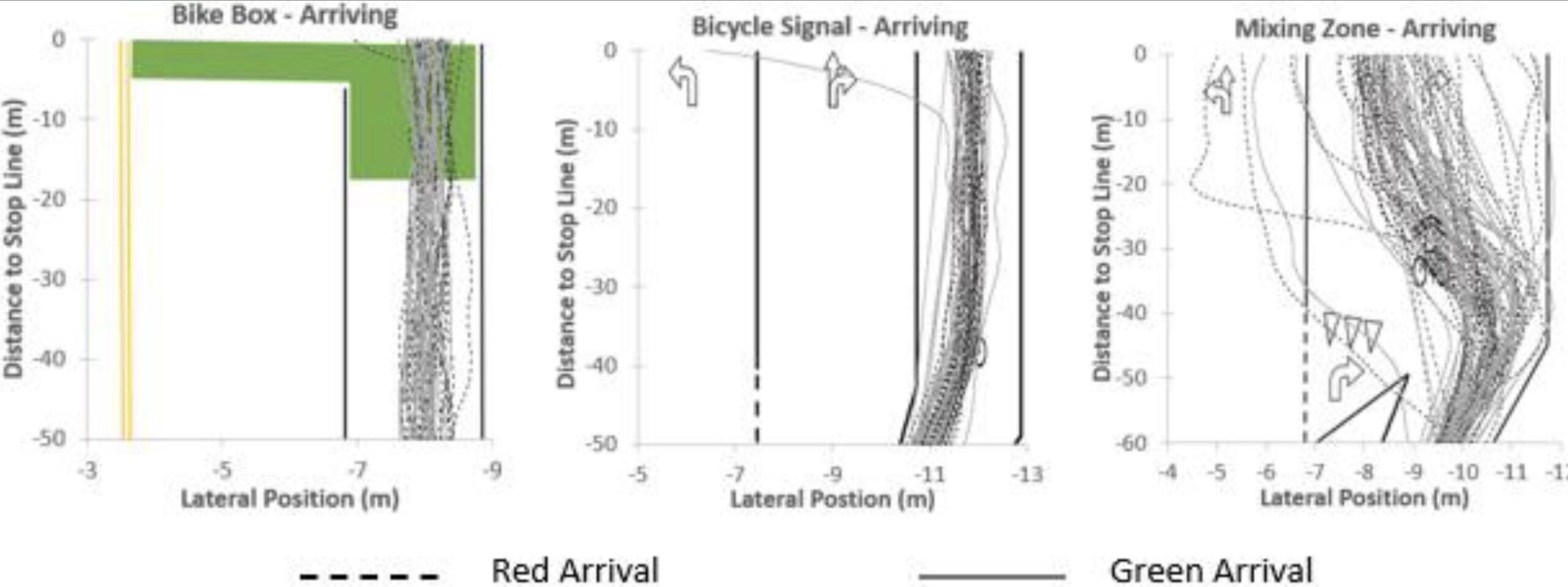

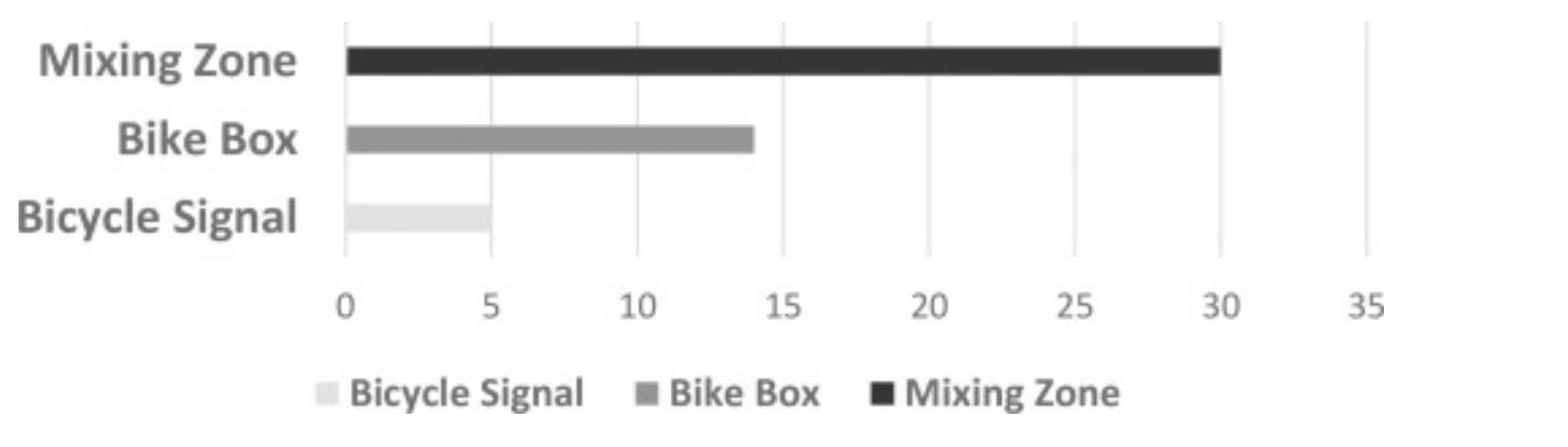

Not surprisingly, the mixing zone treatment “created the most discomfort” among study participants. It also led to the most unpredictable riding behaviors (see graphic). But there’s an important flipside to putting bicycle riders in a more stressful environment: they are more careful. Researchers found that, “The visual attention data of participants [in the mixing zone] indicated that they spent more time looking at the conflict vehicle… it supports [previous research] that a balance of user safety and convenience is an important aspect of creating safer facilities.”

Final verdict:

“The mixing zone may be best fit in scenarios where crashes tend to occur with a pre-existing bike lane, as the positioning data shows that bicyclists are willing to merge with the traffic and the provided right-of-way may allow safer movements between the two modes. The mixing zone treatment brought participants out of their comfort zone and required them to be alert of potential conflicts when claiming lane. Despite this effect, the sporadic and unpredictable riding habits associated with this treatment may expose bicyclists to higher risk scenarios.

Bicycle Signal

The bicycle signal made riders feel the most comfortable. This makes sense since it’s the only treatment that separates all users in time and space — as long as people follow the rules. But similar to the mixing zone, researchers noted an important caveat: Bicycle riders assumed the signals would do their job, so they rode with less caution and made fewer eye movements to make sure conditions were safe. Researchers wrote that, “This might increase crash risk with errant drivers.”

Verdict:

“Despite the high level of comfort associated with the bicycle signal as described in the survey results, there may be a treatment that performs better as the eye-tracking data revealed reduced searching for potential conflicts on approach. For this reason, we suggest bicycle signals be installed only when a clear need is present. “

Bike Box

Researchers liked the bike box most because it struck a middle ground of the pros and cons between the other two treatments. That is to say it offers a measurable amount of safety, while still giving the rider a sense that they should be ready to respond to potential threats.

Verdict:

“In scenarios where there is a large frequency of crashes, the bicycle signal may prove most effective as its design restrict conflicting vehicle movements with the bicyclists… Of the three intersection treatments assessed in this study, we recommend that bike boxes have proven to be the most effective treatment at promoting safe riding habits while also providing improved safety for bicyclists at signalized intersections.”

Do these findings jibe with your experience?

Read the full study here. And check out the simulator lab website here.

Thanks for reading.

BikePortland has served this community with independent community journalism since 2005. We rely on subscriptions from readers like you to survive. Your financial support is vital in keeping this valuable resource alive and well.

Please subscribe today to strengthen and expand our work.

One of the side benefits I see from bike boxes is its normally a no right on red for car drivers. That has a lot of safety implications in itself.

I like the bike boxes best drivers generally respect them, it keeps them from turning on red and gives me a chance to clear the intersection before the driver.

Bike signals I usually try and avoid. The timing is weird like on Hawthorne, overly long like on Rosa Parks and generally confuses or is ignored by drivers.

Mixing zones are a jungle especially when they involve a bus in addition to turning cars.

Lately I’ve been using the left turn bike boxes, when a bike box isn’t present, to get out in front which has similar benefits as a bike box.

Generally. When I was on SE Hawthorne & Madison the other day, a car pulled up next to me in the bike box.

I go when it’s safe to do so without paying much attention to the color of the magic glowing orbs. I also tend to treat all interesections as bike boxes (especially the ones with Xed out boxes*). I vote for bike signals not just for my ease of use but because they slow down SUV/personal-truck/(car)-drivers more than the other infra types. I also see no reason why bike boxes and bike signals can’t be combined.

Absent a bike signal phase, bike boxes need a flashing red to indicate transition to green. I think much of the reluctance to use them properly comes from fear of getting in front of lead-footed cage drivers.

*paint these green PBOT

Aren’t the Xed out boxes to provide room at a tight intersection for large vehicles turning on to the street? It doesn’t seem safe to use it as a bike box.

One of many examples that should be a bike box, IMO:

$50 says PBOT and ODOT ignore these studies like they have every other bit of evidence that car-centric, anti-bike infrastructure sucks and needs to be better.

Looks like ODOT funded the study this paper is based on https://www.oregon.gov/odot/Programs/ResearchDocuments/SPR833FinalReport.pdf

Like anything, it depends on the context. In most cases, I think bike boxes are great because they prohibit right turn on red, allow bikes to bypass the queues, and improve visibility with all the green paint. But a PBOT study a while back showed that they resulted in increased right hooks in some situations, the theory being that they don’t help at all if drivers and bicyclists are arriving on a green, and might cause people to be less careful. I think downhill also was shown to be a problem, like how NW Broadway & Hoyt used to still have high right hooks until right turns were finally prohibited.

So basically, it seems like they should not be used on a downhill or if there is a “green wave” and everyone is usually arriving on a green light. But they are great in most other situations.

Downhill is always a problem.

Less of a problem if there is bike green phase.

Why would a cyclist in a “green wave” go into the bike box?

Advanced stop lines (also know as bike boxes) have two main functions:

1) Greater visibility.

2) Allow for rapid/safe clearance of intersection which is often not possible when riders are queued up single file in a bike lane.

Personally, I’d prefer Dutch-style protected intersections over these three designs, and I’m pretty sure the crash statistics would be better, too.

I’d like to see this study replicated in a driving simulator and see where the driver’s eye tracking goes.

“Conclusion: While the eye tracking worked accurately, we were unable to gauge motorist performance due to the drivers looking at their phones during the exercise.”

I *hate* those mixing zones where the bike lane suddenly crosses over into the middle of the street.

I think understanding how drivers react to these treatments is even more important that cyclists. What actually keeps riders safe?

This is just so much BS:

“But there’s an important flipside to putting bicycle riders in a more stressful environment: they are more careful.”

So because the mixing zone is the most likely to get a rider killed and therefore they are the most panicky, let’s have more mixing zones?

How about we favor designs that don’t get riders killed. Thank you very much.

If you create a design where cyclists are in constant fear, they will just choose a different transportation mode.

I actually don’t think it is. There was a study done in Germany, where they removed street signs and other infrastructure. I can’t recall all the details.

But the finding was that motorists were more careful and there were less collisions because they had to pay attention more to all the other motor vehicles around them.

Have you ever seen old videos of American cities where there were cars, pedestrians, street cars, horse pulled carriages and automobiles?

It looks like total chaos and you’re surprised someone isn’t getting run over every second. Granted everyone is traveling at a much slower pace and there;s no 53′ long trucks but it perfectly demonstrates what both of these studies say about eye movement, paying attention, making calculations, timing, etc.

When all of that’s removed and we give each road user their own lane, a light, a sign, etc it conditions people to rely and trust in lines, lights, signs and disengages them interacting with other road users and with the dynamic situation they’re a part of.

I was hit in a x-walk by a motorist driving in the parking lane at SE 24th & SE Powell Blvd trying to sneak around backed up rush hour traffic in both lanes.

4 years later, I had a friend tell me the other day that every time, the go through that x-walk they think about what happened to me. I don’t trust infrastructure and people obeying infrastructure to keep me safe. I keep me safe.

What is “safest” is what happens when drivers and cyclists interact. Just measuring cyclists’ reactions is incomplete and should not result in a claim of “safest,” as the headline does.

I’ve come to loathe & distrust most bicycle infrastructure for a number of reasons. The biggest one is that it’s different all over town.

If you commute on the same route every day, I imagine that probably works well as you get to know the behaviors of all the road users and know what to look out for.

But as a bike courier for the past 2 years, I often don’t get to make use of most infrastructure as I’m cross-crossing my way around town and I often seen motorists either intentionally ignoring/avoiding bike infrastructure or don’t know how to properly & safely navigate around and/or through it.

Which I believe has made me a much better city cyclist than the man years that I was a year-round bike commuter riding the same route.

At this point, after biking around PDX as a car-free person for 15 years, I really think that there should be a requirement for bicyclists to take a bicycling / pedestrian safety course.

It’s painfully clear to me that we’re all not on the same page out there and many folks, including myself, learn to street safe through making mistakes, getting hurt, having our bikes damaged and having the life scared out of us for a few seconds during a close call.

Seems like “safest” here is relying on bike people feeling uncomfortable enough to be on high alert. I too would like to see how this simulation would show for drivers. I am not willing to place myself at the mercy of an unknown driver in a huge vehicle by riding to the front of a queue & wait in a bike box. Similar with mixing zones. I think there are significant factors that affect the experience of women who ride as well as anyone who might might “look different” (for whatever reason). Speaking from my experience of being bullied while riding.

The study is incomplete. They only measured cyclist’s reactions to the intersections. They need to get the driver’s perspective, too. Even then the results are skewed because everyone in the simulator is really paying attention and trying to do the right thing, unlike in real life.

What’s a bicycle box?

Physics would suggest that safety is better served by examining the behavior of the multiton metal behemoths what can do 60 mph over the 300 lb squishy flesh road users what struggle to get to 25 mph.

As it stands now the existence of this lab is just another piece of evidence for my radical hypothesis that we won’t get real bike infrastructure here until cyclists manage to kill as many pedestrians annually in the US as drivers do.

I truly don’t understand how they didn’t start from That – “hey, what will make drivers kill zero bicyclists?”, as opposed to – seemingly – “what of the like, 3 things we Might do, requires us to do the least?”