In 2013, when the Portland City Council began requiring most new apartment buildings of 30 or more units to include on-site parking garages, housing watchdogs warned that this would drive up the prices of newly built apartments.

Because the city still lets anyone park for free on public streets, they predicted, landlords wouldn’t be able to charge car owners for the actual cost of building parking spaces, which can come to $100 to $200 per month. So the cost of the garages would be built into the price of every new bedroom instead, further skewing new construction toward luxury units.

Three years later, rough data suggests that this could be exactly what happened.

To be sure, this would be only one factor in many that have driven up Portland housing costs. Rents have been rising faster among old units than new ones. But as the city council nears what looks like a tight vote on whether to impose similar mandatory-parking rules in Northwest Portland, affordable-density advocates warn that the story could repeat itself.

Portland affordability advocate Brian Cefola got in touch with us last month to share the numbers he’d crunched using local building permit data published by the U.S. Census.

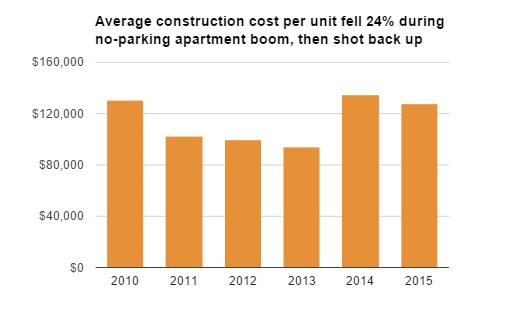

It turned out, Cefola discovered, that the average cost of building a home in a Portland multi-family building dropped 24 percent between 2011, when Portland’s first wave of no-parking apartments began to open, and 2013, when the new city rule took effect.

At that point, the average price returned to its previous levels.

The housing boom and collapse surely play a role in this data, though the exact role isn’t obvious. The international recession and subsequent job collapse began in late 2008; job losses peaked in January 2009. By 2010 — before the price drop Cefola identified — Portland’s economy had become relatively stronger than the national economy, and migration to Portland was accelerating further.

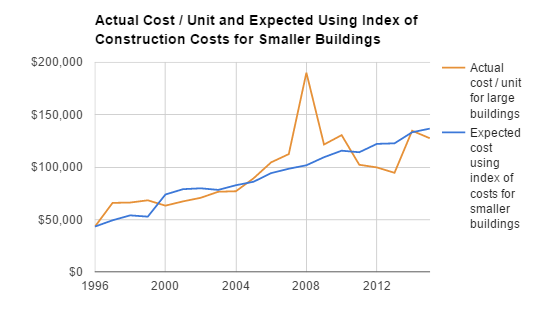

In an effort to correct for changes in labor and other construction costs, Cefola (an insurance analyst in his day job) also crunched the numbers further. Using the cost of building homes in small buildings (one to four units), he created an index of what you’d “expect” units in large buildings to cost if the rules for large buildings hadn’t changed.

That adjusted measure revealed a large, brief spike in per-unit construction costs in 2008, when the recession hit.

Something else it revealed: during the 2011-2013 no-parking boom, the average new Portland apartment cost 17 percent less to build than would have been “expected.” Then it returned to normal.

Data too noisy to draw firm conclusions from, experts agree

Even local experts who oppose parking minimums cautioned that Cefola’s numbers aren’t precise enough to draw solid conclusions from.

“I think it’s really, really hard to draw any strong inferences about the role of parking requirements on building costs based on such aggregate data,” said Joe Cortright, a Portland-based economist who often writes for City Observatory about the unintended costs of overbuilding parking. “The average per unit costs are highly sensitive to what we call composition effects: sometimes developers build expensive stuff in the Pearl (larger units, nicer finishes) and sometimes its spartan studios. So the per unit cost can fluctuate depending on the mix (composition) of the units being built in any particular year. I think that’s clearly what’s going on in 2008–where you see a big spike in the average cost per unit. When the market went south, the only thing that was moving forward, apparently, was pretty high end stuff.”

“This is, alas, only circumstantial evidence,” Cortright wrote.

Chris Smith, a Northwest Portland resident who this month led a successful vote by the Planning and Sustainability Commission against new parking minimums, agreed.

“I would guess that a variety of construction cost factors rising would make it hard to point to parking specifically as a cost driver in the data set we have,” he said.

Advertisement

Cefola doesn’t argue otherwise.

“It’s an indication, and I think indications can be wrong,” he said.

But Cefola, who serves as president of the Grant Park Neighborhood Association in his spare time, said the data lines up with logic.

“Many people warned that it would have an impact on affordability and the kind of construction that would be put up,” Cefola said. “It added this fixed cost per unit. I think people, myself included, warned that it would incentivize larger units, higher-end units.”

(Image: TVA Architects)

There might be no better test case in the city than a project (still unfinished) called Overlook Park Apartments. That project was designed with no parking before the code change, then redesigned with parking after the code change.

The second plan for the building had 17 parking spaces, fewer housing units and higher target rents.

Cefola said he thinks his circumstantial evidence is enough reason for professionals at the city to dig deeper.

“I think there’s this question out there that the city really ought to be answering,” Cefola said. “Given the fact that they say there’s a state of emergency on housing, how come they haven’t made any attempt to assess the parking policy they put in four years ago?”

Interested in parking reform? Come to BikePortland’s wonk night Tuesday to help smarter parking rules build a better low-car city.

— Michael Andersen, (503) 333-7824 – michael@bikeportland.org

BikePortland can’t survive without subscribers. It’s just $10 per month and you can sign up in a few minutes.

The Real Estate Beat is a regular column. You can sign up to get an email of Real Estate Beat posts (and nothing else) here, or read past installments here.

Thanks for reading.

BikePortland has served this community with independent community journalism since 2005. We rely on subscriptions from readers like you to survive. Your financial support is vital in keeping this valuable resource alive and well.

Please subscribe today to strengthen and expand our work.

The Bureau of Planning and Sustainability published a report in 2012 showing how different types of on-site residential parking could impact housing affordability. The link is here https://www.portlandoregon.gov/bps/article/420062

Parking requirements impact housing affordability by increasing the cost of rent and reducing the number of units that can be built on a development sire.

…and that was the last time they looked into it. At the February 26th hearing on the NW District Parking Update Project BPS Director Susan Anderson told the Planning & Sustainability Commission that no studies have been done on what the effects of the 2013 changes were. At a time when housing affordability is the single biggest issue of discussion in Portland, I’m absolutely astounded that they would come forward with proposals to expand parking minimums without even looking at what effect the last round of changes had on affordability.

Your reporting is killing it on this issue, Michael. KILLING IT.

I agree. Michael is a YIMBY superhero.

Great report, and it is certainly not rocket science. Parking minimums increase the cost of construction, requiring developers to take on more debt to pay for the increase. More debt means higher debt service, which means more income is needed from each unit. And with free parking surrounding these properties, developers/owners know that virtually no residents will pay for the on-site spaces, meaning the revenue increase has to be baked into the lease of the units.

I thought this was a biking blog ?

if you think that adding 1000’s of cars and more people to the city doesn’t impact biking, you are living in a fantasy world

The cars are coming, regardless of whether there’s on-site parking or not.

No, it doesn’t (have to) work like that.

Even without climate change (which is a game changer if there ever was one) you can deploy policy levers to discourage, penalize car use and prioritize alternatives.

Sure, and anyone who doesn’t own a place to park their car will continue to have no justification for moaning about having nowhere to park it.

I own, (and pay the debt and taxes on) the place where I store my car when I’m not using it, as well as bear the opportunity cost of not having that space available to put to other uses.

People who do not can whistle.

I kind of doubt that you own and pay the taxes on every single place you store your car. I could be wrong, and oddly enough I do own and pay the taxes on the one and only place I store a car, so I know it is possible, but I still think it is highly unlikely. (Said car is non-operational by choice and is only used to allow me to obtain insurance on those rare occasions when I rent a car (long, convoluted story).)

That’s not what happened in the 2000s: http://bikeportland.org/2015/08/19/portlands-biking-plateau-continues-faces-unfamiliar-problem-congestion-155536

Portland added tens of thousands of residents and 24,000 commuters but only 2,000 more car commutes. The biggest single factor was that the biking rate tripled.

The number of registered cars in Multnomah County is increasing with population growth, but the number of cars per resident is down 8 percent since 2007 (which is also where it was in 2000).

http://bikeportland.org/2015/03/03/multnomah-county-car-ownership-8-since-2007-isnt-rebounding-135184

Maybe, we’ve noticed with our employees that fewer and fewer own cars. They all use a combination of Uber, car share, transit, bike, and walking. At one point only 2 of the 50+ owned an automobile. Autos aren’t going anywhere, but ownership is certainly on the decline.

Car registration is also apparently on the decline. Portland Police regularly report that 20-30% of vehicles in Portland are not actually registered – they no longer pull people over for it, unless there is some other violation involved. Meanwhile, car counts on the bridges continue to rise.

20-30%? My estimate is 5-10% of those on the street. I don’t understand why the city can’t go around and tag these for a few million $ of fees that remain uncollected. Lack of enforcement will convince more folks it is okay to not pay for car tags.

people who bike are being pushed out of bikeable neighborhoods by people who prefer to rent two-car garage mcmansions from the bank. discriminatory exclusionary zoning is a major barrier to increasing active transportation mode share.

Developers are building larger, single houses, even where they could build two (or more). That’s what the market apparently wants and is willing to pay for. I suspect that at least some of the people buying these are not “renting from the bank”, but are buying outright for cash (renting from their bank account?)

All zoning is exclusionary and discriminatory. That’s the whole point.

Do you have any examples of big single houses being built even on lots that could fit 3 or more? I’m sure you’re right — I am definitely interested in this particular scenario and would love to understand it better!

Plenty of examples where one house was built instead of two. One example that comes to mind where more than 2 might have been allowed is that house on the corner of 16th & Division. I think (but haven’t checked) that it is in R2.5, and it looks to be a double lot, so you could have fit 4 houses there. Or I could be mistaken.

I will say, for the record, that I find it an attractive building, and I’m glad they reused the original structure, and am happy with the way it turned out. I am not in the camp that thinks we can provide housing for everyone inside of SE 39th, if only we would build build build.

That’s sort of a unique situation, because it’s a custom house that was commissioned by the current owners. Had that site been redeveloped on a speculative basis by a home builder it’s extremely unlikely that they would have developed it in the same way.

Perhaps, but that doesn’t really invalidate my point. It’s an extreme example, but there are plenty of examples where people are building R5 density in R2.5 zones.

and yet you seem to be unable to be able to offer a single example.

that is an R1 lot. the idea that my comment was directed at the tiny fraction of lots in my neighborhood that are already allow multi-family dwelling is ridiculous.

“That’s what the market apparently wants and is willing to pay for.”

no. developers are building large houses because this is the only way they maximize profit per lot in exclusionary lots.

the market wants apartment buildings as division, hawthorne, ankeny, and belmont clearly illustrate. unfortunately, large swathes of inner SE portland EXCLUDEplexes, garden apartments, cottage apartments, and low-rise apartment buildings despite the fact that these neighborhoods are carpeted with these buildings. and also despite the fact that these neighborhoods are MAJORITY renter.

If someone is willing to pay a lot more for a single larger house then I would say there is a market demand for such a house.

Large swaths of SE Portland exclude lots of things. I know you wish it were different, but I am glad it’s the way it is, because that’s one of the things I have always loved about Portland. I like that there are houses with room for gardens and trees and light and front porches where neighbors get to know one another (renters and owners alike!)

There are parts of the city that cater to those who like higher density, harder surfaces, and a more urban feel for those who prefer it.

“I would say there is a market demand ”

A “market” where every product except for one is permanently unavailable.

If you define the market as “newly constructed apartments in an R5 zone”, then yes, there aren’t many options available. If you define the market as “housing”, then there are lots of different options — houses (for purchase or rent), apartments, condos, high-rise, low-rise, inner-city, outer areas, etc.

All I’m saying is that there seem to be buyers for newly built large houses in close-in areas. I would not buy one, but others apparently will, can, and do.

banning every other form of housing and then arguing that this is somehow valid because there is demand for the one type of housing still allowed is absurd. the neighborhood we both live in has one of the lowest rental vacancy rates in the nation. if housing was demand driven all of 97214 and 97202 would have been upzoned.

I concede it is possible to identify certain combinations of housing and geography that are incompatible under the current zoning rules.

For example, if I want to live in a high-rise apartment building, and I want to do that in inner SE Portland, I will have difficulty doing so. Likewise if I want to live in a house in the south part of the central SE industrial area, I will likewise have difficulty.

Does that mean that houses or high-rise apartment buildings are “banned”? I would say no — I can build/live in either in other areas of the city. But if you are suggesting that apartment buildings are “banned” in R5 zoned areas, I would have to concede that they are, as is building a single family house downtown.

Maybe we are off in this weird fork of the conversation because of a simple misunderstanding. I did not intend to say that our zoning code reflects current market demand; I said that people are building some large houses on lots that could be subdivided, and that there is apparent demand for those, because people are willing to pay high prices to get them.

At issue is that fact that current zoning drives up the prices of all housing, but especially multifamily housing, by allocating so much land to the single-family neighborhoods that you (and I) like. I love living in a single-family home, but I don’t think that choice has wide-ranging public benefits that justify allocating so much of the city to it and it alone. On the contrary, I think that policy amounts to a de facto subsidy of the rich at the expense of the poor, and is therefore unjust.

that’s ridiculous and a good example of amanda fritz fear-mongering.

duplexes and garden court apartments are not 40 story high rises.

no one is arguing for high rises in your back yard. i and others are arguing for allowing the types of buildings that are already in your backyard..

No, it’s an example of the type of building that you can’t find in inner SE. There are, as you say, plenty of smaller apartments scattered around, and you can live in one of those in inner SE if you want.

“and you can live in one of those in inner SE if you want.”

let them eat cake.

Finally! That history class pays off!

“Let them eat cake” was a reflection of Marie Antionette’s misunderstanding of the economic situation in France at the time. Food was in fact available, but the people could not afford it.

So while it may seem an effective as a dismissive comment when you’ve run out of constructive things to say, it runs counter to your argument that we have a supply problem for certain types of housing in certain parts of the city.

Rentals are in fact available, but the people cannot afford them.

It’s hard to get a person to understand something when their equity depends on not understanding it.

I don’t know why you feel the need to constantly insert snide comments into your responses. Please stop it.

please stop advocating for discrimination against lower-income people.

I have to agree, soren. I think most people understand your point that the personal is political but I don’t think you do your position favors by so frequently dipping into criticism of people’s motives.

Michael, When someone openly defends class-based discrimination, I believe questioning motive is not only defensible, but necessary.

This is tiring. It is hard to have a discussion with someone who repeatedly and deliberately mischaracterizes your words to try to score a point. I have staked out a moderate position, (the current zoning code, broadly, contributes to a city I find pleasant and attractive; I support increasing density, but doing so in a way that does not overturn our basic urban form), and it seems the only way you can respond is with ad hominem attacks that border on the absurd.

You are obviously intelligent. You can do better.

Kenton, when an old house gets sold a new mini mansion pops up and a family of 2 + dog moves in.

“All zoning is exclusionary and discriminatory. That’s the whole point.”

Zoning is only exclusionary and discriminatory when it prevents the construction of housing that is desired/needed by other residents. I find it deeply cynical and sad that you believe the point of land-use policy is to discriminate against people who are not like you.

Please don’t lower the level of this discussion to personal insults.

Hi SE,

I had a similar question for Michael way back when he pitched the “Real Estate Beat” to me. But over the past few years I’ve come to see a much broader picture of cycling and the role of BP plays in helping cycling reach its potential.

The way land and buildings are used and developed – a.k.a. “land use” – has a direct impact on the cycling environment. Not only that, but land use can also either encourage or discourage the ownership and use of automobiles… And I think you’d agree that the number of automobiles on our streets has a huge impact on how it feels to ride a bicycle on those streets.

And then there’s the affordability piece. Land use policies that encourage/favor automobile ownership tend to drive up the cost of real estate. And auto-oriented development also makes our city much less dense — which in turn drives up the price of housing.

If we want more people to ride bicycles in Portland, I (as publisher of BikePortland) think it’s very important that we closely monitor and cover land-use and parking policy.

One other thing factoring into my decision to publish articles like this is that I feel we can do it well/better (and with more frequency) than almost any other local news source. As a publisher and editor, I want to utilize all the talents of our reporters. And in Michael’s case, he happens to have a wonderful understanding of these issues and the ability to report on them. That’s such a valuable thing for the community that it’d be a shame to not give it as much of a platform as possible.

Jonathan

Sorry, I can’t agree. This is an advocacy piece, as most of these pieces by Michael are. There is nothing wrong with printing advocacy, but please don’t claim this is journalism.

The piece relies on a housing cost estimate by a non expert and advocate for one side of the position. (The parenthetical about him being an insurance adjuster–what exactly is the relevance? It’s an attempt to give him credibility, but why do we think insurance actuarial work gives you expertise in housing economics?).

The known expert in the field–Joe Cortright–says you cannot draw any conclusions from the data. Chris Smith us a fine person but not an expert in this area, yet Chris is highly skeptical as well.

Quotes from the other side–standard journalistic practice to assure you are not representing just one side of the story? Zero,

And then the story closes with the advocate quotes again, Michael basically accepting everything he says whole cloth.

I’m glad you are covering this, but it’s to a point where I read every story in this series with huge skepticism because Michael has consistently promoted factoids that promote his viewpoint with seldom critical reflection or an attempt to investigate the other side. It’s ok, it’s advocacy. But not journalism, not at least as I understand it.

Who would represent the other side here? Ideally the Bureau of Planning & Sustainability would have studied the effects of parking minimums put in place 3 years ago before proposing to expand them… but they haven’t.

I think it’s to Michael’s credit that he included the skepticism of two of the people he contacted for quotes. When Joe Cortright and Chris Smith didn’t full support the thesis presented it would have been very easy to just leave their voices out.

Why shouldn’t we hear the other side? Sometimes greater understanding happens that way. People on this site have a fear of being wrong or having their beliefs challenged.

Isn’t there a very clear perspective to everything we publish about transportation on this site?

Our journalism strives to be the same sort you’ll read on Salon or National Review or New Republic or Vox or Jacobin or Gawker or the Mercury or Willamette Week: fair but not balanced. It’s an old tradition and it probably describes most news outlets these days. The Oregonian or KGW, by contrast, work from a different tradition that usually prioritizes balance above fairness. That has its downsides too; in my experience it too has underlying assumptions that the journalists sometimes fail to recognize in themselves.

I totally feel you if you’re annoyed by the need to take a grain of salt with this stuff. I agree, you should definitely look for the possible flaws in our narratives! And comment on them right here, so we will see them too!

I hope you’re taking the same salt with everything we write about bicycling, and with everything everyone writes about anything.

The transportation items have a bicycle orientation (which is appropriate), but are rarely editorial. The real estate items feel much more like personal viewpoint, and rarely “newsy”. I think there is a definite difference in tone.

Parking requirements limit development options, limit the density and when they are rampant around a city have an impact on furthering the use of cars–and prioritizing the use of motor vehicles. When cities allow developer to build more density, mixed use walkable areas–they are also much more accommodating to people on two human powered wheels. Some developments never happen due to requirements, or that café or cool store that would have moved into a new building may end up just being first floor underground parking. No café to bike to, higher housing costs cars pulling UP out of subterranean garages over the sidewalk and through the bike lane we go…

And the space for that cafe could also house low-income units.

The proof is in the pudding. Data. Owners will charge every market-rate penny possible when there are very few vacancies available, parking or not. Tenants will pay it, because they must, parking or not. Where’s the beef, as a certain granny used to say. Evidence.

Will we see rents lowered as a result of cheaper construction costs? That’s the beef in this case. And I think it’s in the pudding.

This is well put and I agree. But this data matters for a few reasons:

1) The cost of new construction basically defines the top of the housing market. Except in unusually awesome multifamily buildings, landlords aren’t going to be able to jack the rent higher than the price of new units. So the cheaper we can get new construction, the more competitive pressure existing landlords will face.

2) Part of the problem we have is that a lot of new units are even more luxury-ish than they need to be. That is probably in part because luxury-ish amenities are the way to justify high enough rents to cover the cost of building those additional parking spaces. But they add costs themselves, so things spiral a bit.

3) The single biggest problem we have is that we haven’t been creating new units nearly as quickly as we’ve been attracting new residents. The main effect of raising construction costs is that you get less construction, because the cost of developing a parcel pencils out to profit in fewer situations.

I have heard anecdotally that some no-parking buildings constructed during the boom (the notorious Burnside 26, for example) have already resold for higher prices. So the original developer made out like a bandit — they were indeed able to pocket the extra profit, because the market kept driving up the rents of their competitors. So no, this doesn’t do any good unless the market is also providing adequate housing supply.

Do you really feel we can realistically build units fast enough to keep rents low for everyone who wants to come here (in part attracted by our lower-than-elsewhere rents)? It seems a never-ending cycle, and if we just keep building at that pace, we’re going to end up with a clusterfuck of a city. If we manage to build enough to keep rents down, some other limiting factor will start driving people out — for example a paralyzed transportation system or horrid air quality (both of which we can see the beginnings of).

Whatever it is that ultimately limits our growth, it’s no longer going to be a great place to live.

Is Seattle a clusterfuck of a city, or Vancouver BC, or Boston, or Copenhagen, or Vienna, or Barcelona? All are significantly denser than Portland, on average. In my opinion, all have avoided being clusterfucks compared to Portland largely because all have lower car use than Portland does. That’s the project of BikePortland.

The U.S. cities that have best survived population growth without massive price spikes are in Texas, Georgia and North Carolina. In all of those cases, they’ve successfully created a lot more supply by building lots and lots of freeways to the new suburbs that we have forbidden here in Oregon. That’s worth considering but unfortunately the bills for those freeways and for the physical/emotional tolls people pay when they spend hours driving on them have yet to come due. It turns out that even after correcting for race etc., Charlotte and Atlanta are the U.S. cities that do the worst at getting kids out of poverty. Poor people are already paralyzed by a system that requires car ownership for mobility.

Before parking minimums and density restrictions arrived in the 1920s through 1950s, cities successfully added enough housing units to keep up with population without excessive sprawl: they got rapidly denser. The parts of cities that we built in those years remain the neighborhoods that most BikePortland readers prefer to live in. Biking in Portland (and in all U.S. cities) would be improved if we changed the rules so we can build those neighborhoods again. That’s the project of the Real Estate Beat.

I’m not sure how we are judging cities here, but measured by rents and bike use, I think Portland compares well with Seattle, Vancouver BC, and Boston. Seattle’s building boom is finally paying off in easing rents, but for a while there Seattle rents were shooting up just like they are here. Vancouver housing costs are sky high, which has more to do with Chinese money. Boston has always been pricey. Bike use in Portland is higher than Seattle or Boston, not sure about Vancouver.

All those cities you listed, with the exception of Seattle (which I would say, from a traffic standpoint, is clearly FUBAR) had their basic urban forms established in a very different era. I see no prospect that Portland will radically change density at any point in the near future (the recent Comprehensive Plan update only tinkered around the edges), and the cost of rebuilding significant parts of the city would be very high. In other words, we are not on track to become Vienna in a time frame relevant to this discussion.

Portland can absorb some level of in-migration without problem, but the levels we’ve seen in recent years are well beyond that. Do you really believe we can just keep absorbing huge numbers of newcomers indefinitely without something giving? The first thing to go will probably be the UGB, sadly, because it is required to contain 20 years of “buildable land”. Metro has been pretty creative interpreting that requirement, but that won’t go on forever.

Expanding the UGB will add increasing strain to the transportation system, which is already fraying to the point where even adding bus service (ref. BRT) is problematic due to congestion. That will in turn further degrade air quality, and thus things spiral down.

If we try to keep housing plentiful and cheap to accommodate unlimited population growth, we’ll end up destroying the city in one way or another.

Hmmm…. I’m sounding uncomfortably like 9watts here…. Sorry everyone!

PS Are you sure that Minneapolis and Boston have lower car use than Portland? I’ve lived in both places, and that statement does not fit with my experience.

If Portland builds enough housing, and expands its transit systems, the city can handle in-migration. Population density here is considerably lower than some other US cities and many European cities.

The housing is being built. It just takes time to catch up, after a long and very deep recession that essentially wiped out five years of building. The transit is, in my view, the bigger problem.

Agreed. You can fit far more people in a bus on a bus-only lane than you can in the same space if everyone drove alone. We just need the backbone to start taking space away from cars.

So how do we get this backbone? I think we are far from a societal agreement that we should take what most people will perceive as a radical step, and without that consensus… how can it work?

We need to start with “trial” projects. Use cheap methods like paint, cones, and plastic bollards to mark out bus only lanes. Collect lots of data during the trial. Then, when everyone sees the benefits with their own eyes and realizes that their worst fears never came true, make it permanent. This is the same approach that BetterBlock and Janette Sadik-Khan took. More often than not, the best approach is just to get the project on the ground and let everyone experience it first-hand.

We already have an example of how a bus only street works downtown. Sure, it would be trickier to implement on the less redundant east side, but it’s not impossible. It would also have the effects of calming traffic on the street, so it would benefit people not riding as well as drivers too.

IMO, the proposed changes in the comprehensive and central city plan represent the most significant upzoning in PDX since I moved here almost 20 years ago. The language also is very supportive of future revisions.

I wouldn’t describe the either the Comprehensive Plan or the Central City 2035 as containing a significant amount of upzoning. For the most part the Comp Plan leaves allowances from the 1991 zoning code in place. In the entire Central City Plan District boundary the only sites receiving additional FAR are the main Post Office (soon to be owned by the PDC) and the University Place Hotel (owned by PSU).

I see lots of grey on my side of the river on pg 736:

https://www.portlandoregon.gov/bps/article/564277

And the map tools suggests to me that most of those changes involve upzoning. In particular, I am pleased by the significant bonuses.

The changes in grey on that map are pretty minor, and do not represent major upzoning. For example the change from IG1 to EX near OMSI mean that it would be easier to develop office space than it is now. The change from RX to CX to near PSU means that residential would no longer be required… but given that residential is likely the highest and best use of those sites it’s unlikely that it makes any difference.

Also, the Central City 2035 Plan is mostly taking away bonuses, not adding them. If anything, that represents downzoning.

the map tool indicated that many of those sites did not previously have bonuses. is this incorrect?

If you give me a specific property I’ll look at it.

Suppose you are a developer. Your goal is to maximize profits. The cost of building a high end apartment building is not that much greater than the cost of building a mid range apartment building, and the rents are much higher. So as long as there is sufficient demand for high end apartments in the neighborhood, that is what you will build. If something happens that lowers your construction costs, you won’t choose to lower your rent or to build mid range apartments, you’ll just happily make more profit on your high end apartments.

You highlight the borderline case where a given property cannot be profitably developed into apartments, but perhaps could be profitably developed if parking was omitted. How common is that? I see apartments being started all over the city, including in neighborhoods that I’d describe as mid range and not that close-in. Obviously they are expected to be profitable, even with the parking requirements. So eliminating parking requirements wouldn’t have made the difference between those being started vs not started. The only effect is that the developer would make more profit if he can omit parking.

The borderline properties you are talking about would, I think, be further out, toward the outskirts of Portland, where desirability and rents are lower. NE Sandy past 82nd, let’s say. Suppose low end apartment projects that are not profitable today, would be profitable if there was no parking requirement. Then perhaps removing parking requirements might spur those projects, and perhaps the city should consider waiving parking requirements – in those areas, specifically. (Note that, to the extent we want increased density, this might not be desirable.)

“The housing boom and collapse surely play a role in this data, though the exact role isn’t obvious.”

One factor is that banks are only now starting to loosen restrictions on lending for multi-family units or condos compared to single-family homes. Insurance companies are also only beginning to be willing to underwrite these developments. Yes, I realize we’re now eight years past the collapse, but this is what we’ve seen with the three of the four condo units that changed hands in my building in the last three years. 60-day (or longer) closings are also still the norm, I’m told by Realtor friends.

I know this is only one of many factors, but I suspect lenders requiring high qualifications for borrowers would drive prices higher, combined with lower inventory versus demand in that time frame. You might think it would cause units to sit on the market longer and drive prices down, but I think you’ll find the reality is counter-intuitive to that – again, in that time frame (which coincides with a continual post-recession rise in the stock markets, economy and job growth).

Armchair economics… 😉

pete, there was no rental housing bubble.

the housing bubble was largely restricted single family dwellings…and the housing bubble is back! portland’s single family housing prices are at all time highs after increasing at the fastest rate in the nation y-o-y. buy now or be priced out forever! it’s always a good time to buy!

There was indeed a rental bubble – the number of people owning went down dramatically and thus needing to rent went way up. I can introduce you to several people who saw the coming of a spike in rental demand coupled with opportunity to buy (foreclosed / bank owned) housing to rent for pennies on the dollar in anticipation of that demand, myself included. I have one friend who lost his job then and now owns at least 12 properties across the country, from Antioch, California to Memphis, Tennessee – he wanted to make damned sure his income (and his daughters college education) was no longer dependent on his employer’s stability. Mid-2008 saw the end of “stated income loans” and everybody and their brother getting multiple mortgages on singular properties, plus the government allowed banks to sit on huge numbers of foreclosed homes indefinitely… yet people still needed to live somewhere. At the same time others, typically older and more established people, saw real estate with an emphasis on “real” – there will always be demand for desirable land/properties.

The housing bubble was not restricted to single-families, not by a long shot. Entire multi-family developments went bankrupt across the US, as did huge numbers of commercial projects. But although joblessness jumped dramatically, there were still large numbers of people who profited by sales and/or equities in their homes (and the tax advantage of $250K/500K capital gains free), and as I mentioned, when banks only lend primarily on single-families, those are the properties that will jump in value the most.

So, what happens when you don’t have the credit and/or down payment to buy, the homes available for you to buy jump out of reach, and you need/want to move to cities where there are jobs/growth? Rents go up. Way up.

Look, you want affordability? Erie, Pennsylvania. Flint, Michigan. Go where the jobs aren’t, and the people don’t necessarily want to be. This is part of where the “build more housing, stupid” commentary this site is now known for falls flat on its face. Especially in a city with strict Urban Growth Boundaries.

On a side note, I just saw the movie “The Big Short”, and highly recommend it.

There is and was a rental shortage, not a bubble. There was no overbuilding of rental property to meet speculative demand. If you watched the big short and payed attention, you should understand the difference.

It’s also maddening to see people claim that the rental shortage in PDX is a new development. Rental vacancy rates in inner PDX has been absurdly low since I moved to PDX 16 years ago. Artificial scarcity is not a bubble.

“The housing bubble was not restricted to single-families, not by a long shot.”

Thanks for the strawman.

The rental vacancy rate peaked along with the bubble. There was no run on rental housing during the housing bubble:

http://static1.businessinsider.com/image/54aa9ecc69beddf826870503-599-378/homeownership-2.png

There *was* an increase in rental demand as a consequence of the housing bubble collapse due to people being forced to move out of single family housing into apartments. Effect does not equal cause.

Pete, I concur regarding your comment about 60-day closings on condos. I’m a board member of my COA. We had 3 units sell in the last 9 months, and all units took almost exactly 60 days each. Despite different lenders, and occurring in different months of that 9 month period.

Also, by observation, I can tell you that many condo units selling in today’s market will sit without price reductions. Why? Because the limited inventory means the seller can wait for the right buyer (usually all cash, or much cash) to pay their list price, or close to it. And “waiting” in this market can be a whole 4 weeks! Not a long wait.

Rumor has it, condos may be returning soon as developers may no longer be risk averse about the statutory period, and recognize that the low inventory is good for bring more units on the market. That said, how many mid-market condo will be part of this mix of new condo is uncertain. Luxury units (call them market rate) are the trend now, but hopefully not forever.

Thanks for the feedback – we saw one unit sell low because the owner had already bought a new single-family property (ironically from my ex-girlfriend). The others simply sat (under rental) for various periods until the market caught up, which it seems to have now. My banking friends have said that condo lending is starting to become a little easier, and I’m also starting to see underwriters again for our business insurance, which I’ve been shopping to change for quite some time now. Time will tell!

So charging for street parking at the same rate as a parking structure would increase rental affordabilty.

Charging for private property storage in the public space would be good policy city-wide. Unfortunately, it is very unpopular.

You’re right. I can’t imagine cyclists sitting still for having to pay to park their bikes in the public spaces.

Just curious…anyone know why the Overlook Park Apartments are takings so long to build? It’s more than a year late and they are still probably 6 months away from completing it. Are other projects having these delays?

Yeah, I have no idea. I looked through the building permit stack while working on this story and couldn’t figure it out.

Is it possible the money isn’t flowing into the project to make it happen? Developers typically don’t pay cash for their projects, but depend on (sometimes a series of) construction loans.

http://bikeportland.org/2016/03/28/average-apartment-building-costs-fell-sharply-during-no-parking-apartment-boom-179149#comment-6644516

Lets look at the bright side. In the not-too-distant future when the age of happy motoring is over all these indoor parking spaces can become low cost living spaces with the addition of tents, shipping containers or tiny houses. Or if we don’t end happy motoring soon they will become handy boat docks for use after rapid sea level rise.

Allowing camping in the former parking garage would be a cheap way of increasing average affordability without having to actually do something!

I hope people renting these apartments truly do not own a car but the skeptical side of me says many do and just park it on the street wherever they can. There was a story in WW a few years ago about a survey of residents of apartments with little or no parking, 72% own a car and 66% park on the street. http://www.wweek.com/portland/blog-29452-apartments-without-parking-dont-equal-apartments-without-cars-says-city-study.html. This what is KILLING livability in densely populated areas.

Strange definition of livability isn’t it? If livability is only being able to park your car, then move where there are no people. I think that the reason there is a parking problem is that the place is EXTREMELY LIVABLE.

Yeah, it’s the old, “Nobody goes there anymore because it’s so crowded” situation!

They do now, but the numbers will go down over time. We need to build for the transportation mode share we want, not the transportation mode share we have.

Livability issues can be fixed by making it more expensive to have cars and park them on the street on the street, so that fewer people do it.

I think this raises a big question for city parking policy, and I hope they answer it. After all, they did research on raising the minimums in the first place for a problem which, however one might categorize its significance, was not a declared state of emergency. Surely the city can put the same effort into a problem, housing costs, which is.

Brian “BJ” Cefola

Seems fairly obvious that omitting parking makes it cheaper to build an apartment building. Other factors may well have affected the $/sqft cost around that time, but with-parking/no-parking is certainly one of those factors.

But isn’t the real question whether the rent is lower in newly constructed no-parking apartment buildings versus in equivalent newly constructed with-parking apartment buildings? Is there non-circumstantial evidence for this?

Because the goal isn’t to enable greater profits for developers. The goal is to increase the rate of new apartment construction and to lower rents for tenants.

Neighborhoods (or at least some people in neighborhoods) oppose no-parking apartment buildings because the burden of providing parking for the tenants’ cars gets placed on the neighborhood, which includes the tenants themselves, as everyone drives in circles looking for parking. Instead of on the developers, who get to enjoy extra profits by off-loading that burden on the neighborhood.

At least one city commissioner lamented that recent housing construction has been “luxury”, and it’s an idea I see frequently in discussion of housing. I think higher construction costs bear directly on that, upscale units can more easily recover extra development costs.

What developers want to build is not high cost or low cost units, but profitable units. As long as people are willing to pay high rents, landlord are going to charge high rents.

To me the most tiresome comments here on bikeportland are variations on the that’s just how it is line. This way of looking at the world skips over the fact that there are very specific, identifiable reasons why things are this way, and that we could—if we wanted—change them. But this defeatist/pragmatic line doesn’t admit this possibility.

Just because there are wealthy people who are only too eager to gobble up expensive condos or apartments or single family houses doesn’t mean that we should defer to *the market* when it comes to our housing policy, or that we couldn’t through financial instruments or other policies change the incentives or relative profitability of different styles of housing, etc.

If you had some practical ideas of how to change the dynamics of the housing market, I would love to hear them — I don’t much like the way things are going any more than you do. For the record, I do NOT believe the housing market should determine our housing policy, though it may place constraints on what is possible.

Well you are familiar with one plank of my platform for tackling the present housing challenge: stop pretending that population growth/migration into the metro region is automatically salutary and/or inevitable. I don’t think it is either of these, and I think we’re unlikely to get a handle on this problem until we wrestle with the demand side of the equation as well.

I mostly agree with you, but can think of no workable solutions to address the issue.

I can think of a great many possible ways to proceed, but think it best if we were as a region to find ways to grapple with this collectively. My concern is that many feel similarly to you and because it seems difficult (it probably will be) they prefer to think about something else. But I don’t think avoiding this issue is a reasonable strategy.

It is illegal for a state to prevent people from moving between states, or to penalize people for doing so (e.g. withholding benefits from recent arrivals). See constitutional right of freedom of movement, in the Privileges and Immunities clause of the US Constitution, and the numerous Supreme Court cases applying this.

In theory, perhaps a private business could decline to hire, or rent to, anyone who has recently moved into a state. I’m not sure, without doing done research, if this would be permissible. But why should said business do so?

And until last year it was illegal for gay people to marry….and two generations ago black people couldn’t use the same facilities as white people. Laws get overturned all the time, and sometimes this can be a salutary thing.

All I’m suggesting is that when constraints loom (that were unrecognized when a given law was passed) it may be time to revisit some of those laws and the thinking that led to them. The world is shrinking every day, and getting fuller. There’s no point in my view in dredging up the interstate commerce clause and related statutes as a way to shut down this conversation. Far more interesting and useful to interrogate what we might do about the present situation. Those who are being priced out of their houses and apartments right now aren’t served by this backward looking approach.

The effects of closing our doors to outsiders would have massive implications that I am not quite sure you have considered. I honestly can’t see any good coming from it.

that sort of simplification is a transparent attempt to make the conversation, the issue, go away. how about this – you read the Rockefeller Commission Report and get back to us. I linked to it just two weeks ago in response to a similar comment from you.

“After two years of concentrated effort, we have concluded that, in the long run, no substantial benefits will result from further growth of the Nation’s population, rather that the gradual stabilization of our population through voluntary means would contribute significantly to the Nation’s ability to solve its problems. We have looked for, and have not found, any convincing economic argument for continued population growth. The health of our country does not depend on it, nor does the vitality of business nor the welfare of the average person.”

http://history-matters.com/archive/contents/church/contents_church_reports_rockcomm.htm

I don’t think the main objections are to the thesis that limiting population growth might be beneficial, but on whether it can be done on a regional (or urban) basis.

You may be right, but I’m pretty sure we have not yet had either conversation.

According to the most recent census data, Oregon grew by 58,000 people, or 1.5 percent, from July 2014 to July 2015. Net in-migration accounted for 42,935 people, or almost three quarters of the growth. The population growth rate due to births exceeding deaths is very low.

I’m therefore not sure why it’s relevant to respond to someone who is pointing out that Oregon can’t legally stop people from move with a quote from a report that appears to be about the rate of natural population increase.

9watts: that report is over 40 years old. I question its relevance today, as it could not take into account advances in agriculture, energy, etc. that help sustain our current population.

I’ll tell you why I think it is relevant.

Because by refusing to have a CONVERSATION about population growth (all varieties) we just defer the inevitable reckoning, make it that much more painful. Right now our policies subsidize and encourage and reward in-migration and population growth, are premised on it continuing, and our economic system (so we tell ourselves) is dependent on it. We’re unlikely to make inroads on those fronts without first coming to terms with the scale and scope of the issue.

40 years(!) Well that is clearly out of date.

How about the constitution? Or The Clean Air Act? Are they also automatically obsolete?

Weird.

Well now that you mention it, yes the Constitution is out of date. Documents should be constantly re-evaluated and updated as needed, (in the spirit of the original intent, of course). This is why we pass amendments. Major amendments to the Clean Air Act were made in 1970, 1977 and 1990.

Except you didn’t suggest amending the Rockefeller Commission report, you dismissed its relevance before reading it. I’m all for wrestling with what the report’s conclusions were forty-some years ago, updating it, revising it if we were to determine that it could use it. But to dismiss it without reading it based on ‘agricultural advances’ suggests that you would benefit from reading the document to see if your critique is on point.

There is a difference between granting rights and denying rights.

How about instead of preventing new people from moving to Portland, we compel existing people to move away? That would be equally illegal, equally unfair, and equally effective at reducing housing pressures, so wouldn’t you be equally in favour of it? Or is this whole obsession with stopping in-migration really just another version of the grumpy old man yelling “get out of my yard”?

And, by the way, I don’t think anyone is refusing to have a conversation about population pressures, but since you seem to be the person most interested in having said conversation, maybe it is up to you to facilitate having that conversation in a productive way?

Perhaps you should do a “guest post” in which you not only a) explain your goal to reduce in-migration, but also b) flesh out the actual facts behind what you call “policies subsidize and encourage and reward in-migration and population growth, are premised on it continuing, and our economic system (so we tell ourselves) is dependent on it”, and c) suggest some realistic and feasible actions that would accomplish your goal. Then we could have some substance to converse about.

I haven’t read everything you’ve posted, I don’t even read every thread here. But I don’t recall seeing such a post/thread. And it is a big and complex topic, so simply lobbing it into every comment thread about other topics isn’t the best way to make your point. In my opinion.

“the burden of providing parking for the tenants’ cars gets placed on the neighborhood”

city-subsidized parking is a burden? i would very much like the city to provide me with some similar “burdens”.

Many people do find the lack of on-street parking a burden. You can spin it how you want, but that doesn’t change the fact that they do find it a burden, and that it contributes to opposition to higher density in the inner-city.

This is why we need to make taking the bus or MAX more convenient than driving. Don’t want to deal with parking? Take the bus!

This requires not only expanding the MAX system, but improving bus headways to 5 minutes so that transfers are much less painful.

the wait times for trimet LIFT are unacceptable during peak periods. a small progressive increase in income or property taxes would easily fund a dramatic improvement in transportation equity. i would enthusiastically pay those taxes. how about you?

LIFT is a massive money-suck. Costs per ride averaged $32.97 last month, vs. $2.46 for MAX and $3.16 for bus (source). However, LIFT is not only a federally-mandated service (through the ADA), it is an invaluable service for people who need it. Although, TriMet should be working on improving regular service for people currently using LIFT to take some burden off the expensive service. This includes expanding service and decreasing headways. I would certainly be in support of additional taxes to pay for this.

Personally, I would. Not sure how widespread that feeling is.

We don’t often see electricity shortages or water shortages (for much of the country, yet) because these commodities have a demand, but they also have a price a person pays to use them. Cities all over have the commodity of on-street parking, yet often only look at the demand when $x = $0. What would be the demand if you had curbside beer at $0, or if you had it at a higher price. The demand would be different.

The supply needed would not be as big of a concern if the parking was properly managed.

It isn’t the case that 100% of people drive, yet the people who pay rent or property taxes pay for the higher costs of off street parking that is required, while also paying the costs to build and maintain on street parking. Many pay these expenses while not receiving much, or really any benefit from this “High Price of Free Parking.”

If we wanted to reduce the cost of maintaining a street, could we simply ban parking on it? I would think reducing the “parking subsidy” would save money. Would a wider, more open street be an improvement? Or would it just encourage drivers to go faster?

I would think in that scenario it would make far more sense to

– install bioswales,

– widen the parking strip for green space/pervious surface

– sell the strip of land now vacated to adjacent homeowners with the stipulation that it become green space

That would basically require reconstruction of the street, no? Drainage, crossings, the actual digging things up, affected utilities, etc. Do you think this would really save money?

Why not just sell the space as it currently is, without any additional work?

that was my third suggestion above. It would raise gobs of money.

Ah, I that was the third part of a 3-part series. If the point of the move is to reduce the cost of maintaining parking, why not sell it without stipulation?

My thinking was that you’d need to have some stipulation about use otherwise you’d leave yourself open to one property owner putting in a garage, the next a swimming pool and the third a bioswale in that annexed frontage. I’d think you’d want and perhaps need some more continguity.

I don’t think too many people would build a garage in the parking section of a road… it’s rather narrow. I think most people would use it to park their car.

Ripping up the street would be enormously expensive, far overwhelming any financial benefits to be gained by getting rid of it so it would no longer need to be maintained.

Just take a walk down 50th Avenue to see how lack of parking encourages speeding. 50th technically has a parking lane but it’s almost never used, so the travel lanes effectively become 20 feet wide, and this encourages people to drive too fast. You can see this on Foster Road as well. If the parking is not used, then the parking lane should be converted into a protected bike lane and the roadway narrowed.

Good point John – and to a certain degree, that’s happening.

Good article. My frustration is that the parking impact of a new project on the existing neighborhood is probably the biggest issue. The Overlook Park Apartments are an especially problematic project. Yes, it now has 17 parking spots. That is good because there is no on-street parking to the south (the park and Interstate Ave next to the MAX station), the west (the park), and the east (Kaiser’s lots). That leaves the neighborhood to the north and some on Interstate Ave to the north for parking. I know no one has a right to public parking in front of their residence. Again, it is the impact of the change. Some other projects had on-street parking nearby. This particular one may require 2 to 3 block walks where that was not an issue previously. It will make it more difficult for the sports teams that often come from significant distances to use the park. I am hoping that the city will ask Kaiser to help out by allowing use of their West Interstate facility after hours. I would be dreaming to think they would allow parking for this new project after hours. It will be very interesting to see the impact when it opens. I hope it works, but I am not optimistic.