(Image: TREC at PSU)

What’s the best way to separate bike and auto traffic?

Portland hasn’t built many protected bike lanes yet, but the ones it has include dabbles in every major separation method, from the mountable curbs on Northeast Cully to the plastic posts on the Hawthorne Bridge viaduct to the thick fence on the Morrison Bridge to the big round planters on Northeast Multnomah to the parked cars on Southwest Broadway.

As it aspires to make protected bike lanes its default bike lane design and prepares for a high-profile downtown project, here’s a recent bit of data that might inform the city’s choices: people seem to love planters.

A study presented at Portland State University last month by a recent grad is the latest to show that, for whatever reason, a giant flowerpot in the street seems to be pretty much the most popular way to protect a bike lane.

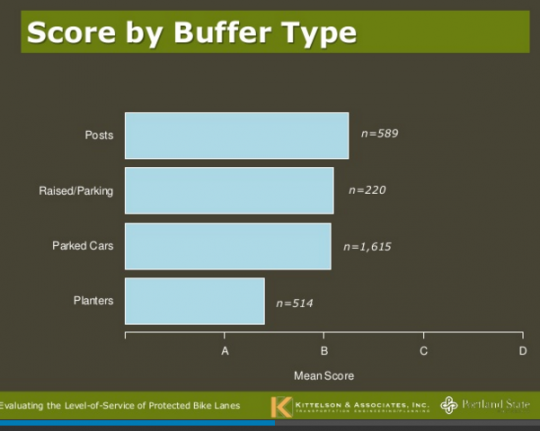

Here’s a clip of Northeast Multnomah Street that PSU grad Nick Foster, now working as a senior planner for the Boise office of Kittelson and Associates, filmed and shared with hundreds of people to ask how comfortable they’d feel biking in it. It was one of 23 clips from bike lanes in San Francisco, Chicago and Portland that Foster drew on to create the data in the chart above.

“They look nice; you can see over them,” Foster said in his Nov. 21 presentation at PSU, summarizing the two biggest advantages of planters.

A 2014 study of bike users in Hangzhou, which is arguably the bike capital of China and has an extensive network of bike lanes protected by greenery, found that “beautiful surrounding environments” was a meaningful reason people enjoyed biking for transportation.

Advertisement

Planters come in lots of shapes and sizes. In terms of appearance, the planters in downtown Vancouver BC make some of the nicest-looking bike lanes I’ve seen:

…but they lack one of the big advantages of Portland’s planters, which is that it’s easy for a person on bike or foot to move between them, either to cross the street, to get ready for a left turn, or to get around an illegally parked car or other obstacle.

One big downside of Multnomah’s planters is that they take up so much of the road’s width. They probably wouldn’t be possible, for example, if the general travel lanes on the downtown transit mall were closed to cars in order to create north-south bike lanes. There’s not much room.

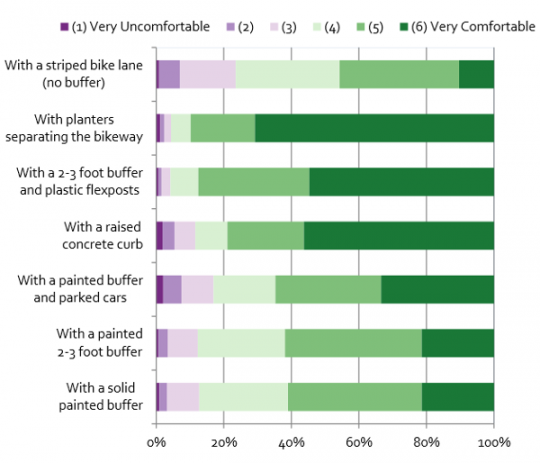

Foster’s finding about planters echoes an earlier one from his professor and co-author Chris Monsere, which used still images to ask people how comfortable they’d feel in various contexts:

One notable difference is that plastic posts fared much more poorly as a separation method in the video than they did in the still image, which may not have conveyed how flimsy most bikeway posts are.

“Posts are a nice reminder,” Foster said in his presentation last month. “But everyone knows that a post goes down very easy.”

— Michael Andersen, (503) 333-7824 – michael@bikeportland.org

Thanks for reading.

BikePortland has served this community with independent community journalism since 2005. We rely on subscriptions from readers like you to survive. Your financial support is vital in keeping this valuable resource alive and well.

Please subscribe today to strengthen and expand our work.

Anything will do, so long as they start doing something.

It looks like this study completely agrees with you.

Assuming a 4 and better as the more likely candidates to ride a bicycle to begin with. I’m actually surprised how little any of it really changes between the different forms of bike lanes.

All forms other than “bike lane” are at the 80% approval rating or better for the the 4+’s. Which of course begs the question on how much money do we dedicate to fewer “great” lanes at the expense of a greater number of “better” lanes. Especially considering your an approval rating difference of less than 10% in most cases.

And what does it say of raised curbs (by far the most expensive to install of all of them) that they rank no better than a lane with a painted buffer?

little clay pots with geraniums?

How about “air” as in overhead elevated bikeway? 😉

I say Yes Mr. Boulanger.

Very easy to get from that bike facility to adjacent businesses, prep for a left turn, etc., not.

Why not build bioswales to separate people riding bikes from car traffic? There’s already an example of this on Naito just north of Lincoln and it works great. This also solves the problem of water pooling in cycle tracks since it would be grated to drain into the swale.

I meant to type graded, not grated, although I suppose the swale would have grates too. 🙂

great idea… drivers will learn quickly to stay away from the curb lest their vehicle become high-centered and they’re stuck waiting for a tow and blocking traffic…

maybe make the plants of the softer variety so riders can fall into them safely…

I was thinking the same thing a few weeks back when I was wading through the lakes formed during a heavy rainstorm. Downtown seems to have very few green streets, despite the need. Other than SW Lincoln, the only bioswales I can think of are ones built by private developers as part of a larger project.

It would be fantastic if BES / PBOT could do a joint project along one or two corridors running through Downtown. It would be a great way to build out a protected bikeway network and help prevent stormwater overflows. Of course, that’s the kind of cost effective joined up government thing conservatives say they like but actually hate (witness what happened when Sam Adams proposed a similar idea as a way to build out Neighborhood Greenways).

I think the bioswales are designed to allow runoff to enter the soil somewhere near the surface. So they’re only useful where there is soil that can absorb runoff and let it percolate down to the level of the water table.

In downtown, you have limited soil, and you have a lot of buildings with basements up against the sidewalk.

In most of downtown you’d have a problem of no non-compacted soil to allow water in, or water leakage into building basements.

On the other hand, maybe they could just dig a hole 75′ deep and pipe the runoff directly down to the water table.

For instance, I’ve always wondered about this bioswale on SW 16th and Everett — https://www.google.com/maps/@45.5250084,-122.6876634,3a,75y,92.77h,85.82t/data=!3m7!1e1!3m5!1sXC0qaNf9TAIEboiDPESLEw!2e0!5s20090401T000000!7i13312!8i6656

Just on the other side of 16th is the I-405 freeway trench, which probably has massive pumps to drain any infiltrating groundwater into the sewer system. So it appears that the city build a groundwater recharge bioswale 100′ away from a location where ODOT has a groundwater removal pump system in place.

(Or, maybe the bioswale drain is piped down 40′ to below the level of the freeway, IDK).

FWIW

Ted Buehler

Wow. That would be an interesting question to get an answer for. It does at first glance look like a classic case of “not my job/not my department”

Could it be that the pumps to drain the freeway trench are routed not into the sewer but into dedicated stormwater facilities that flow into the Willamette?

Older neighborhoods in Portland have are generally CSO, the graphic here

http://www.portlandonline.com/portlandplan/index.cfm?c=52254&a=298497

shows that downtown, Northwest and the Pearl fall under that description, but the 405 dig is relatively new. (40 years or so) and there’s a green line surrounding the Freeway trench labeled CSO boundary.

Swales are of two types. One type filters, retains and infiltrates water, the other detains and filters before putting it into a pipe. Either can be built anywhere, it’s just the infiltration type needs a larger reserve space where the ground is less permeable.

the second type reduces the sediment and pollution load at the treatment plant.

Thanks for the info, paik.

I’m going to guess that the 16th and Everett bioswale is a “filter, detain and put in a pipe” variety.

Ted Buehler

Very expensive (excavate, form/pour concrete, plant). Maintenance (people throw trash in them). Dangerous (when a cyclist crashes into the bioswale).

If bioswales are dangerous then so are curbs…and probably more so since sidewalks do not have swampy muck to break your fall.

I’m thinking that when you crash your bike into a bioswale, you might land on the soft soil at the bottom, but you might land on the hard concrete walls . . . or head butt said walls.

They also place 1″ steel plates at the bottom of bioswales, perpendicular to the direction of traffic to slow water. Falling on one of those could easily be fatal.

The somewhat new separated bike path along SW Multnomah Blvd., between 30th & about 20th (east bound) does this. It is pretty sweet.

Isn’t that a sidewalk, or at least a MUP?

Speaking in general, think for a moment about what you’re asking for. If you have a sidewalk fronting a building with enough room for people to walk comfortably, even if someone is stopped to look in a window, take a nap, smoke a cigarette, is walking a bike going the other way, or a person is hanging out at a table with a big scary looking dog that a cafe set up etc…and then a barrier or at least a curb, and then a wide bike lane that can comfortably let cyclists pass/ride next to each other to be social, and then a bio swale that’s wide enough to serve as a waiting area for a transit stop, then a lane for transit vehicles, then a lane or more for general traffic, or at least emergency vehicles/freight, maybe a turn lane etc….complete streets require a tremendous amount of real estate, and will never be common in Portland, because the streets are too narrow. Bioswale protected bike lanes will make sense in some places. Where they make the most sense there’s something on the above list of street uses that’s not in demand. Like on that section of Naito you mention, no buildings on that side of the street, so minimal foot traffic.

Did we actually need to spend any money to figure this out?

A student did the survey for his/her school project, it didn’t cost “we” a dime.

are we really still using the term “protected” to describe things that aren’t protection? yes, I’m still campaigning for people to use the correct terminology…

mountable curbs, plastic bollards, and empty parking spaces are not protection, they’re separation…

even the NE Multnomah planters are only spotty protection because there’s plenty of space for a car to get between them and crash into bikes…

the Morrison bridge path is true protection, but it’s a horrible path with both directions of bike/ped traffic all using the same surfaces with no markings to let people know where to go… when biking east I have no idea if I should be on the “sidewalk” section of the path so that I’m staying right, or if I should be on the right side of the newly laid raised path in the middle of the path… when walking east should I be on the right side of the path or the right side of the original sidewalk? some paint would be nice…

Portland has no protected bike lanes… none… there are only separated bike lanes…

can we please stop calling them “protected”?

Well, most of the cycle tracks in Copenhagen or Amsterdam aren’t totally protected (typically just a curb), yet most people would consider them the gold standard for bicycle infrastructure.

I agree with you, though, which is why I prefer the term “cycle track” over “protected bike lane”. Cycle track implies a separated, bike only lane that is more than just a painted lane in the road surface. SW Moody is an example of a cycle track only separated by a curb, yet it works well for its function of keeping people from driving/parking in it.

No one understands what a cycletrack is. Protected or enhanced bike lane is immediately understood.

When most people hear “cycletrack”, they think of a velodrome or something like it. Protected bike lane is the best term, IF it is used to described a lane that has actual protection. Paint and/or plastic sticks are not protection.

i think painted buffers afford modest protection (esp. from encroachment and door zones) and significantly improve comfort.

s/cycle track/bikeway/ — tight shorts not required

I’ll guess that a big part of the “gold standard” is the speed of adjacent traffic. From what I’ve seen, they seem to have a larger buffer for fast streets (31mph is the max in cities) and the curbside bikeways or advisory bike lane are on streets with 30kph (18mph) speed and shared spaces are limited to 9mph (plus maybe 2-4mph over, not our “live and let kill” 11.) More speed, more space and/or protection.

At 30mph, it’s noisy and unpleasant to be within 15ft of traffic — you can’t have a conversation without shouting. So, everywhere in Portland because we don’t enforce traffic laws.

Most of the cycle tracks in Copenhagen aren’t really protected, they are sort-of elevated bike lanes. But the cycle tracks in the Netherlands are as protected as anything on the planet. Dutch (not Danish) protected bike lanes are the Gold Standard).

It’s all relative. If we’re going to war against inaccurate use of the term “protection” when applied to bike facilities, I prefer to focus on the two prime offenders: “parking protected” bikeways and buffered bikeways. I do not consider SW Broadway (a “parking protected cycletrack”) or SE Foster (a “buffered bikeway”) “protected bikeways.”

If the bikeway is delineated by something you wouldn’t want to hit with your car — a curb, wand, planter, etc. — I’m content with calling it “protected.”

Paint doesn’t cut it and if nobody happens to be parked…a “parking protected cycletrack” is, like a “buffered bike lane,” just paint.

This is why the Federal Highway Administration prefers the term “Separated Bike Lane.” But “Protected” just sounds better, so I think that is the one that is more widely used.

the solid planters don’t allow bikes to merge in or out, but they also mean UPS trucks won’t be merging in either.

also: what’s up with that first chart? the axis is odd, it’s unintuitive that the smallest/lowest bar is the most popular.

You’re misreading the graph. The bars are olive, and extend from the right; the background is light blue.

heh.

Categories in Reverse Order is imperative here.

I prefer the bike lanes that have only painted lines as buffer. I like the way it provides a kind of passing lane for riders to overtake slower riders exercising their right to ride to the middle left of the bike lanes.

If those painted lanes weren’t half in the door-zone, then slower riders wouldn’t have to ride in the middle left of the lane.

Agree.

I’m trying to see how someone passes me with my cargo cart in that narrow segregated bike lane, especially with the extreme crowning that it has. I’d much rather have the entire space available so that those who want to roll in the gutter can and those who want to ride closer to the motorized traffic can. Also, those planters are far too close together to allow for safe transitions out of the segregated space for left turn movements and such.

A proper one wouldn’t have a gutter and you could ride right up against a 2-inch angled curb.

Good to have these data, but it’s pretty clear that in America, larger numbers = better.

The graph at the top would probably be more intuitive if it showed preferred treatments as larger bars, instead of smaller (reverse the scale).

I’d recommend Edward Tufte.

Michael can you explain that top graph? Why the n’s are so discrepant and what the heck a mean score of A, B, C, or D means? This is all based on how people felt when watching videos of each, there is no hard data to show ridership increases or crashes or anything right?

I looked through the slides and was very disappointed that there was not a single example of infrastructure that is best practice in Amsterdam or Copenhagen. We need to stop setting the bar so low.

In NYC, they have trees on West St. (formerly the Westside Hwy.) separating auto traffic from the Hudson River Trail, which in turn is separated from the sidewalk by another group of small trees. Peds, bikes and auto traffic each have their own set of traffic lights at sugnalized intersections. There are some YouTube videos which show this trail northbound from the WTC/Freedom Tower area to the George Washington Bridge. New York does this pretty well. Worth checking out.

It really irritates me that planners are fixated on what north-american cities with 1-4% mode share are doing. There are dozens of cities with 20-50% mode share in europe that have been building effective bike infrastructure for generations. There is absolutely no need to re-invent the mistakes that europe discarded.

Europe’s great and all, but the fact is that the built environment in European cities is fundamentally different from the environment in most North American cities. History and whatnot.

So while we should definitely look to Europe for inspiration and concepts, it is in fact *quite* useful to look at North American examples for implementation. Even if they haven’t achieved high mode shares yet.

We can’t expect a city like NYC, which has only been working on bike infrastructure with any degree of seriousness for a decade, to have reached the same level of success as Amsterdam or Copenhagen. Doesn’t mean they haven’t figured out some valuable things that may be more applicable to Portland.

“but the fact is that the built environment in European cities is fundamentally different”

Europe is not a monolithic area and many cities in europe with high mode share do indeed resemble parts of portland.

Sure, Europe’s not monolithic. Also, plenty of cities (and countries) in Europe have mode shares nearly as low as what is typical of the United States. And yes, some parts of some European cities look somewhat like what one might see here. But they still operate in environments with different laws, codes, and standards, not to mention user expectations,

All I’m saying is that the solutions in Amsterdam and Copenhagen are tested in their environment, not in ours. You can use the lessons Dutch and Danish cities have learned, but you can’t assume everything that works there will work here. And you can’t just throw out good things done in US cities just because the US is in the aggregate less good at bicycle transportation.

Then there are also the cultural differences.

Also, the Hudson River Greenway is a great example to look at in terms of alternatives to the current bike lane on Naito.

The Q&A with Rick Browning linked to in this article is now 6 months old. I’ve asked this on here before, but has anyone heard when PBOT intends to even begin outreach on the Central City Multimodal Project?

More evergreen street trees are needed!

The large bushy kind that grow really thick tree trunks, have shallow roots that break up sidewalks, and block any form of light – even nighttime street lights – and obscure visibility?

Can’t evaluate the results because the slides are incoherent. The survey says it has N=219 but the bars (see the one above) have much larger N’s. What is he counting?

The distribution of ridership among the respondents (see the slides) indicate that 50% say the “never” ride bikes, another 25% say they ride at most once a month. Yet the responses are going to be overwhelmingly based on folks who never ride.

I don’t know maybe the dissertation is better than this, but this is really impossible to understand.

Yes, I’m a scientist, glanced at the slides for a few minutes, and still didn’t understand how the research completely worked. I’m guessing the talk must have filled in the holes, but if you’re just looking at the slides, it’s fairly confusing.

It’s so funny that planners feel the need to reinvent the wheel. Just widen the sidewalks 12 feet and you are done. Instead we need all manner of fancy with mountable curbs. Wow, we had sidewalks for several centuries…but now we need something else?

I have watched a few films on the dutch cycleways. A lot of large sidewalks with lanes painted. Cheap and easy.

Oh wait, riding a bike on a sidewalk is criminalized in quite a few places. Woops!

we’ve had sidewalks for several centuries? What did a sidewalk of 1700 look like?

I have posted a response with links but my post is caught in approval purgatory at the moment.

Dutch cycleways are not large sidewalks with lanes painted on them. The cycleways are at a different grade, with different materials than sidewalks. Newer cycle paths are regular asphalt with a layer of pigmented asphalt on top and a short angled curb stepping up to the sidewalk.

It comes as no surprise to me that folks riding bicycles like planter boxes best.

1) A person driving a car can’t smash through them, like the plastic bollards, a curb or a painted buffer. So there’s a clear safety advantage.

2) A planter can’t decide to park in the cycletrack, like someone driving a car can do with a parking-buffered cycletrack. So there’s a clear operational advantage.

3) They’re pretty. All the others are ugly. So there’s a clear aesthetic advantage.

Basic preference for a safe, functional, attractive environment for bicycling.

It’s good to see that the data support basic human preferences for things.

Ted Buehler

the planters on hornsby in vancouver made it hard for me to see people exiting into intersection. unless i was specifically looking for people cycling they were invisible because my peripheral vision fixated on the rows of planters (and their vegetation).

the preference for raised bed bikeways in europe comes decades of experience and an acknowledgement that clean sightlines are essential for safety. it’s sad that this survey did not include a single example of this type of infrastructure.

Soren — Hornsby, in Vancouver BC, and you were in a car? Agreed that planters make it harder for people in cars to see people on bikes. And therefore very dangerous, because it can easily result in a right hook fatality.

I rode the Hornby and Dunsmuir cycletracks when they were new in 2012, and was dubious as to their net benefit. (This after being a regular bike commuter in the area in the 1990s when there were no bike lanes anywhere in downtown Vancouver).

I’m still dubious about cycletracks/protected bikeways for any number of reasons. But I’m less skeptical than I once was. And of the ones I’ve traveled on in Portland in the past few years, I prefer the planters to any of the other options that aren’t a guardrail. (curb and noodles on E Hawthorn Viaduct, parked cars on SW Broadway, raised curb on NE Cully, a few painted buffers).

FWIW

Ted Buehler

I drove by them and rode them on that trip. I think protected facilities work well if they are designed well.

I was a fan of plastic bollards until I watched what cars did to them on the Lovejoy ramp of the Broadway Bridge.

Yep, bollards are cheap and protect no one. We should not tolerate them. Steel polls? I would go for that. Or…gasp…a real curb.

Carl wrote:

“until I watched what cars did to them…”

Maybe it was cars, but it was certainly mail trucks.

The intersection isn’t wide enough for a semi truck with a 53′ trailer to make the turn onto Lovejoy while staying in the assigned lanes.

I saw at least one mail truck go crunch-crunch-crunch through the remains of those bollards before they finally disappeared.

FWIW,

Ted Buehler

Part of the nomenclature issue is the difference between the designers and usual users. If a ‘barrier’ can have various levels, or gradations, of permeability, then, by extension, it can have a permeability rating that ranges from 100% (air, painted buffers, etc.) to 0% permeable (raised bike pathways (not depressed), walls, and the like).

So, a ‘protected bike lane’ would also fall under such classifications. The classifications help quantify safety, but don’t necessarily tell typical users what they will encounter.

Separated bike lanes, maybe graded (levels?), is a better term, IMO, and could be used better to describe facilities. There must be analogous classification systems that can be adapted.

if we are going to motivate the “interested” to use new infrastructure then messaging is important. “protected bike lane” is an attractive term while “separated” and “track” have negative connotations.

No option for “shopping carts full of stolen bikes”? Or “abandoned tents full of trash and dirty needles”?

I’m very curious to know the survey methodology and the profile of actual respondents to the survey.

Dave, I actually spent about 20 minutes on the slides, then viewed the video (no, he didn’t fill in the holes), and tried to find the dissertation. The link is broken. But thanks for the ad hominem.

I was trying to be nice, but since you want more detail:

1) This is as about as far from a random sample as you can imagine. They invited in respondents for the in-person survey from the Park Blocks Saturday market on two weekends in a row. The researcher claims generalizability because one weekend was during Thanksgiving and therefore more people were at the market.

2) Slide 18 indicates that about 145/219=66% of the respondents are less than 40. According the Census, about 40% should be in that age category. No other demographics are provided.

3) As I noted already, on Slide 19, he reports that 170/219 respondents say they never ride a bike (about n=70) or ride 1-2 times a month (another 100) for recreation.

4) And then finally, the bars have N counts that don’t correspond to anything.

It’s important to have good research to help make public policy choices, but there is also a lot of junk research. If a piece of research is going to be promoted like this, it’s incumbent to allow experts to understand the methodology. Michael promotes it because it supports his agenda. Fine. You may like this piece of research because it reinforces your biases.

And you’re right, I’m in the business of research design. And this one at present is lacking any information that allows an outside observer to evaluate its credibility.

Thanks, that’s sort of what I thought.

I’ll take a curb or concrete bioswale wall over a car. The former don’t tens to make sudden movements.