“They claim to be making progress in reducing emissions, which sends a powerful message to policymakers that we don’t need to do more and we can take our time.”

– Bob Cortright, 350 Salem

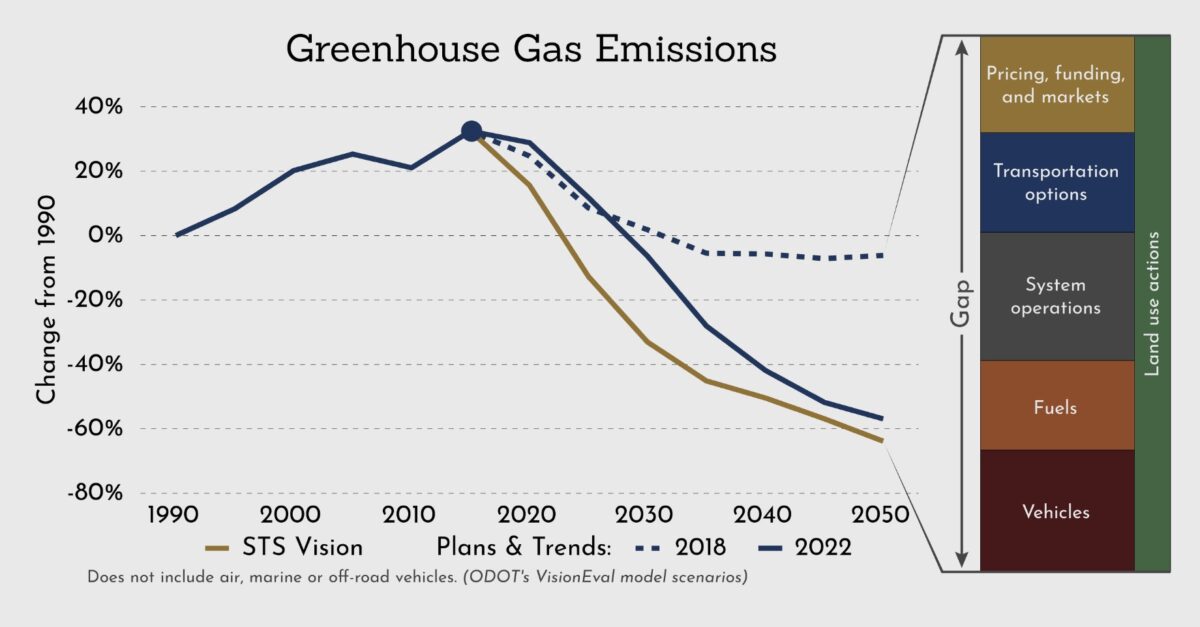

Five years ago, the Oregon Department of Transportation did not have reason to be hopeful about meeting their greenhouse gas emissions reduction goals. ODOT’s 2013 Oregon Statewide Transportation Strategy (STS) calls for the agency to reduce transportation greenhouse gas emissions 80% by 2050 (compared to 1990 numbers), but a 2018 monitoring report (PDF) said emissions were only projected to fall 20% by 2050. And in 2020, the leader of ODOT’s (newly formed) Climate Office said, “We’re heading in the complete wrong direction,” when it comes to carbon emission reductions.

Fast forward to 2023 and the climate crisis is more dire than ever. The most recent report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), released earlier this week, made it clear that time is running out to avoid climate catastrophe. But over at ODOT headquarters, the mood is more optimistic. According to a new website unveiled March 9th, the state is on track to reduce emissions 60% by 2050, which is “short of the 80% goal, but still a dramatic improvement from 2018 projections.”

Great! Now we can just sit back and relax, right? Not so fast.

A closer look at assertions made on the website casts doubt on that rosy picture. Advocates are not only skeptical of how ODOT frames their emissions efforts — they worry the website and PR push behind it could placate policymakers and the public into a false sense of progress.

What’s on the website?

The website is a dashboard detailing ODOT’s progress toward its overall goal of reducing emissions by 80% by 2050 (see chart). ODOT outlines two objectives for this goal: reduce growth in vehicle miles traveled by using “land use laws, incentives and policies to support reductions in the number of driving trips people take and how far they drive each trip”, and clean up each vehicle mile with “new technology to reduce emissions via the kinds of vehicles people drive, such as electric, and the kinds of fuels used to power those vehicles.”

In order to meet these objectives, ODOT has split their actions into six categories: transportation options (which concerns public transportation, biking, walking and rolling and transportation demand management strategies); pricing, funding and markets; vehicle technology; land use; system operations and fuel technology.

It all sounds good, but some agency watchdogs don’t think the new website provides sufficient information to back their claims.

An analysis of the website on Salem bike news blog Salem Breakfast on Bikes calls it “unconvincing…propaganda more than sober analysis, a bit of a slick farrago.”

“The structure is designed to look informative, but in fact it obfuscates. If the progress were truly so great, the structure would be more transparent and easier to parse,” the Breakfast on Bikes article states. “More specifically, it lacks any detailed discussion of what changed between the 2018 forecast and 2022 forecast.”

Salem-based transportation and climate advocate Bob Cortright (twin brother of No More Freeways co-founder and City Observatory writer Joe Cortright) also has some qualms. He reached out to ODOT staff about his concerns, writing in an email to several staff members that he was “troubled by the absence of analysis to support the broad claims about progress” on the website.

“While [the website] is very good at providing a high level description of the broad range programs and efforts to reduce emissions I do not see links to the detailed analysis that supports the conclusion in the press release,” Cortright wrote.

Suzanne Carlson, who leads ODOT’s climate office, responded to Cortright’s email last week. She said the team is “working on some updates to how information is displayed in the website to better highlight the key assumptions and inputs,” which they expect to have ready soon. In an email to BikePortland yesterday, ODOT Public Affairs Specialist Matt Noble said ODOT is working on a new webpage for the site that should be made public during the first half of April.

“The new page will give more insight into our progress since 2018, and what changed to allow for the 60% forecast emissions reduction. We’ll handle requests for deeper data dives on a case by case basis, as that level of detail is beyond the scope of the site,” Noble said.

Without this information, Cortright said the website seems to present a dubious conclusion that could cause people to rest on their laurels.

“They claim to be making progress in reducing emissions, which sends a powerful message to policymakers that we don’t need to do more and we can take our time,” Cortright told me. “It sends a message that we’ve done something in the last five years to turn this around…there are lots of reasons to be skeptical of that conclusion.”

Active transportation stats

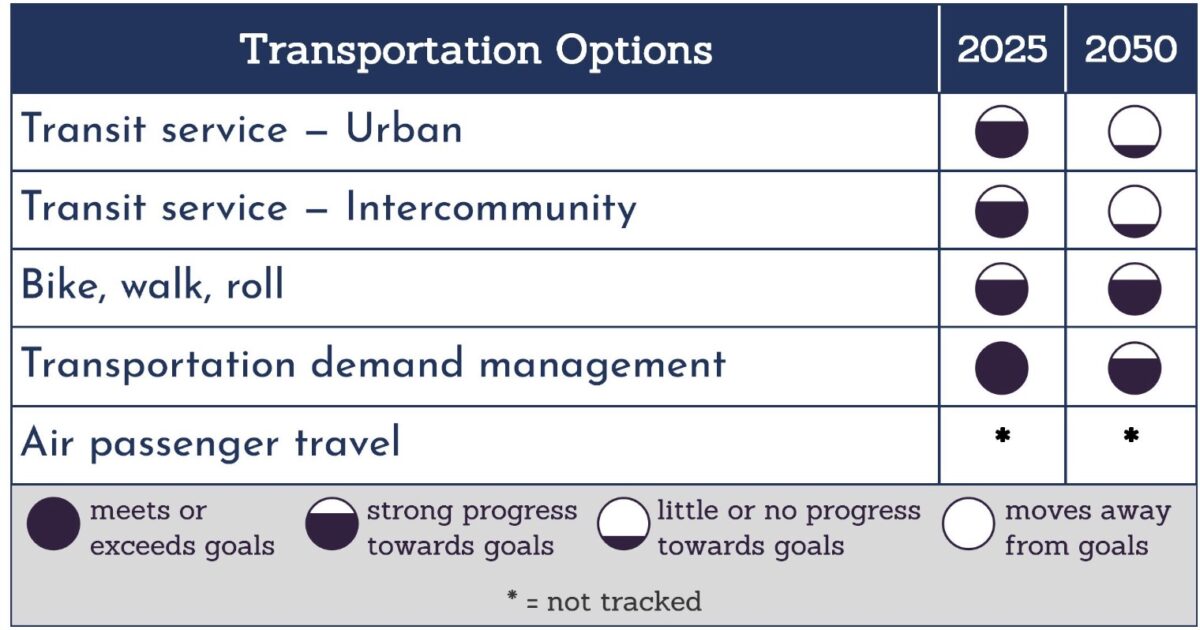

The website features a page analyzing Oregon’s progress toward the state’s active transportation goals.

“Transportation options create opportunities for Oregonians to use active modes of transportation on Oregon’s system. Especially ones that emit less greenhouse gas emissions like biking, walking, rolling, scooters, carpooling, public transit, and passenger rail,” the website states.

Here is the vision ODOT has for what active transportation will look like in Oregon in 2030:

- By 2050, 30% of short trips (under 20 miles) in urban areas will be made via biking, walking or rolling.

- By 2050, a majority of urban households have equitable access to biking, walking, and rolling options close to their home.

- The Oregon Department of Transportation continues to provide and expand dedicated and reliable funding for bike and pedestrian infrastructure through 2050.

Sounds pretty good — how are we going to get there?

Apparently, we’re not so far from meeting the first goal as it might seem: ODOT claims that 12% of Oregonians travel by walking, biking or rolling, citing the Oregon Household Survey conducted from 2009-2011. (The survey they linked to actually said the number was 11%). Even better: they said this number has grown during the pandemic. But when BikePortland tried to find a source for this statistic, it was nowhere to be found. When BikePortland reached out to ODOT for more information about this, they walked back that claim.

“Some data we looked at suggested this, but on further scrutiny, we’re going to remove that line from the site until we have more data certainty,” Noble wrote.

When BikePortland tried to find a source for this statistic, it was nowhere to be found… they walked back that claim.

Considering Portland’s bike ridership numbers have gone down substantially in recent years, it is surprising to read the opposite is true for active transportation statewide. The Breakfast on Bikes article calls this out, questioning why ODOT would use data from more than 10 years ago to calculate progress on statewide bike goals and saying the dashboard “misuses that data for unwarranted optimistic ends.”

“There are no grounds from this one data point to infer any great progress. And from the Portland bike counts, it looks like there are strong grounds to infer a lack of progress,” the article states. “On the whole the dashboard looks like slick bells and whistles and greenwash rather than substance.”

At the same time as the website lauds statewide active transportation progress, ODOT says at the current rate of investment, it will take over 150 years to close gaps in pedestrian and bike infrastructure. But they go on to say funding for this purpose “has improved in recent years,” referencing the $255 million in federal funding for active and public transportation the Oregon Transportation Commission approved in 2020 as well as the $30 million allocated for biking, walking and rolling projects over the next five years from the Infrastructure Investments and Jobs Act.

To reduce VMT or not to reduce VMT? That is the question…

As mentioned earlier, the dashboard outlines two objectives: to reduce vehicle miles traveled (via things like investing in active transportation) and cleaning up the car transportation that does occur. These are good objectives — but they have to work in tandem. Advocates say ODOT’s actions have indicated they are focusing more on the electrification element than the VMT reduction part, at everyone’s detriment.

The website highlights the fact that progress towards cleaning each vehicle mile is driving ODOT’s progress and there are significant gaps remaining when it comes to reducing VMT.

“This objective has the most opportunities for improvement. Trends suggest that Oregonian’s driving habits won’t change much through 2050 if the state doesn’t make progress here,” the website states.

In a conversation with BikePortland yesterday, Cortright pointed out that the advances in clean transportation aren’t necessarily ODOT’s doing. The Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) is the agency responsible for setting fuel standards and managing large parts of the state’s electric vehicle program (including by administering a ban on purchasing new gas-powered cars by 2035). ODOT has been involved in car electrification efforts, but not all the progress can be directly attributed to their work.

Cortright said although ODOT is acknowledging the state hasn’t made adequate progress on reducing vehicle miles travelled (VMT) overall, their departmental focus on increasing car capacity through projects like the I-5 expansion at the Rose Quarter flies in the face of this stated concern.

“It’s not that we don’t know what it will take to reduce emissions,” Cortright said. “We need to stop expanding highways.”

Underlining Cortright’s message is a recent interaction he had with Oregon Transportation Commissioner Lee Beyer at the March commission meeting. At this meeting, Cortright made the case that ODOT needs to do more to reduce VMT in order to significantly reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Beyer’s response wasn’t encouraging to Cortright and other advocates.

“That’s more of a societal attitude issue rather than something that I think [ODOT] can do directly,” Beyer said. “I think as we move to less environmentally damaging cars, EVs or whatever, that people will continue to drive, because they like the freedom of personal mobility.”

All in all, it’s apparent that ODOT staff and the commissioners overseeing the agency have varied perspectives about how the state is going to reduce its transportation-related emissions. According to Beyer, electrification is the most reasonable step, because it’s too difficult to change people’s behavior. But ODOT knows VMT reduction is a crucial part of the equation.

“Yes, we need to electrify the fleet, but that doesn’t get us there. In terms of vehicle miles traveled reduction. We really need to change the way we provide options for people if we’re going to accomplish that,” Cortright said at the OTC meeting. “And I think people do respond when we provide an environment and choices other than driving.”

Thanks for reading.

BikePortland has served this community with independent community journalism since 2005. We rely on subscriptions from readers like you to survive. Your financial support is vital in keeping this valuable resource alive and well.

Please subscribe today to strengthen and expand our work.

ODOT is plainly not interested in reducing VMT in any way shape or form. They view unlimited car mobility as a positive for society, and will do anything they can to further that end – I mean Beyer said that himself. To ODOT, as long as traffic “flows freely”, it doesn’t matter how far Johnny Regular has to commute to his job in a suburban office park, it doesn’t matter how sprawled out the metro area is, and it certainly doesn’t matter how many pedestrians die on the roads to achieve that end. Unlimited automobility is the only thing that matters for transportation in the state because Lee Beyer thinks “people like it”.

The 30% of Oregonians who can’t or don’t drive? They don’t matter.

The thousands of pedestrians sacrificed at the altar of “free flowing traffic”? They don’t matter

The destruction of what’s left of the bucolic Oregon countryside in the name of suburban sprawl? That doesn’t matter.

The social cost of isolation and suburban sprawl? That doesn’t matter.

None of that matters to Lee Beyer, or to Chris Strickland. They have no positive changes to make to our state transportation system. We will get more cars, more traffic, and more sprawl and we will like it.

Comment of the week! (or the year).

To be fair, their view is shared by a broad majority of Americans and Oregonians.

I see nothing on even the most distant horizon that would relieve Johnny Regular from the need to commute to his job in the suburbs, and without point-to-point transit, driving will likely remain the most attractive option (if not the only viable one). It’s not like we’ll be demolishing the office parks and bulldozing suburban housing — people will be living and working there for the foreseeable future, and they’re going to need to travel.

Your 30% figure includes many who can’t walk, bike, or take transit on their own either, so it’s kind of a bogus number. According to the Oregonian “Even in bike-and-transit-loving Portland, there’s still a passenger vehicle parked at about 85 percent of homes.” Outside the city center that proportion is likely much higher.

It is probably unfair to blame problems like social isolation and destroying bucolic landscapes on Beyer or Strickland. It would make more sense to blame the legislature, who tells ODOT what to do, but probably the real culprit is the general public (minus those right-thinking advocates who hang out here) who do not want to trade their comfortable homes in the suburbs for a small apartment in the city center and get everywhere by bus.

[https://www.oregonlive.com/commuting/2014/01/seatle_still_beating_portland.html]

I think you might be surprised. If you asked most Americans if they want an expressway running down their local main street, they would (almost) unanimously say no. If you take a quick glance at property values near freeways, you’ll find them to typically be lower than the neighborhood at large. Even Americans don’t like unlimited car mobility when it affects them directly.

People (generally) understand mobility through the lens of traffic congestion, and ODOT manages congestion at the land-use level by reducing density. But there is a large amount of academic research to show that reducing density doesn’t even meaningfully reduce traffic – since it forces more sprawl, and makes public transit somewhere between inconvenient and impractical. ODOT acts as if unlimited suburban sprawl is better for traffic than mid-rise apartment buildings on SE Clinton, which is something that should be obviously wrong to people.

Even if 85% of Portlanders still own cars, they own far fewer than their suburban brethren and they drive them less. Living in a neighborhood where you don’t need to drive means you drive less (shocker). ODOT will not allow municipalities to even come close to building places like that without conceding.

ODOT is the authority in the state on transportation matters. Surely they influence the legislature just as much as it influences them. This isn’t even a knock on them – it’s just how government works.

I fully agree. People want the mobility, but they may not like the costs. Nonetheless, I see no sign that Americans are asking for reduced mobility, even if they want its costs reduced.

ODOT does not control landuse.

I would say lots of Americans are asking for reduced car mobility. They just don’t really frame it in that way. Living in a walkable area is something that lots of Americans want, and that certainly runs counter to car mobility.

ODOT may not directly control land use, but they play a very large role. In this article, Jonathan notes that a MMA (multimodal mixed-use area) is the only way around state land-use laws that require more car infrastructure for more intensive development. ODOT is the sole authority which can give a MMA. So a bit of a gaffe from me, it’s the State Conservation and Development Department. But still, ODOT does have authority to circumvent parts of that to allow for more density – but they only do when they can get something in return for it.

Living in a walkable area is not at all equivalent to asking for reduced car mobility. What they’re saying instead is that they like the ability to do things without driving, not that they want to be restricted in their freedom to use their car.

And we can observe that many people in these areas still have cars, and still use them for many purposes.

Most landuse decisions are made at the city and regional level. The areas where ODOT has any influence are very limited.

Living in a walkable area is, practically speaking, asking of reduced car mobility. Walkable areas restrict car access and use by design (sometimes intentional, sometimes not) – inner Division is walkable because a higher proportion of the right of way is given to pedestrians than on outer Division. Feeling safe to walk around means slower cars, fewer cars, and more space for pedestrians. All of those things involve reducing car mobility. People may still have cars, but they use them much less and in different ways than people who live in unwalkable areas. I own a car, but almost exclusively use it for furniture shopping, camping, and picking people up at the airport.

ODOT’s land use influence is piecemeal and varies by city. In a place like Forest Grove, where they have direct jurisdiction over all the primary roads they have quite a lot of influence. In Portland, they evidently have enough influence to force the city to allow a freeway expansion they don’t really want – which is not insignificant (although still limited).

That is true. But I don’t think people generally equate saner traffic in their neighborhood (which I think most people want) with reduced mobility (which I think most people do not want), and I think to the extent that driving is more difficult for people living in walkable environments, people would see that as a cost, not a benefit.

What you’re really arguing, I think, is that some people (like you and me) are willing to pay the price of reduced mobility in order to live somewhere walkable. I would totally agree with that. But what you’re actually writing is that people want the reduced mobility, which I think is absolutely wrong.

Because reduced car mobility is a necessity of a walkable neighborhood, I view the reduced car mobility as a benefit – it allows walkable areas to exist. Having less car mobility means having greater non-car mobility – there is a direct trade off between the two. If you want more of one, you also will get less of the other and there is no real way around that.

Not true. I live in a very walkable neighborhood (95 walk score), and have excellent car mobility as well.

ODOT has full time lobbyists that influence legislature as their job. I had one assigned to me that followed me around the capital for a bit. Most of their top level employees make regular rounds of influence in Salem as their job. I’ve personally seen ODOT employees lobbying in House Rep. and Senators offices. They say they are educating legislators, but mostly it’s a cabal of paid ODOT lobbyist. Keeping this a float.

The whole Bridge Replacement Project will be paid for by re arranging the State Transport projects (all of them) to the bottom of the lists after the I-5 widening. Even with federal funding.

Somebody run against the incumbent House Rep.29 the chair of the Joint Transport Committee. Forest Grove, Cornelius and west Hillsboro is the area you’d have to live.

Only b/c car use is NORMALIZED. If car use were an outlier, people would make decisions that are based on factors other than the historically crazy idea that someone can drive tens and even hundreds of miles per day with no consequences whatsoever.

Your idea that no one is going to trade a comfy house in the suburbs for an apt in the city depends *entirely* on the normalization of car use. I know people who make a point of living close to their jobs so they can walk, bike, or take the bus. No one *has* to live dozens of miles away from a workplace, but people choose to b/c they can. It’s really that simple.

Sure — if things were different, things would be different. But in this world, car use is normalized; it is convenient; people generally want increased mobility, and a car provides that. It’s not the only possible arrangement of things, but it is the arrangement we’ve got.

The idea that people might prefer living in a house in the leafy suburbs vs. in a dense apartment is the result of much more than a normalization of car use. It’s also a desire for quiet, reduced crime, privacy, space, a garden, access to greenspaces, clean air, good schools, and many other factors.

Some people choose it because they can. Others don’t. Not everyone wants the same things, luckily.

And meanwhile the planet will die, and we will die with it. Great!

An important step in changing the world is acknowledging the way that it is, and understanding why.

If you want people to voluntarily reduce their consumption of CO2 emitting fuels, we need to find alternatives that are attractive. Luckily, in the case of driving, we are transitioning to electric cars, which, while still having some significant problems, are much better than gasoline powered cars in the many important respects.

Lament it all you want, but I believe it is not possible to build a environmentally and fiscally sustainable public transportation system good enough that it would replace cars for most people most of the time without completely rebuilding our cities (an effort that would in itself not be environmentally or fiscally sustainable).

We need different solutions now than we did in the 19th century.

Can’t afford even my old 650sq ft apt. in the city anymore, so I live in the burbs and go everywhere by bike & bus.

“ODOT outlines two objectives for this goal: reduce growth in vehicle miles traveled”

They don’t even say reduce VMT. Just growth of VMT.

Unfortunately, Cortright is being intentionally obtuse with this claim.

Modeling in the PNW strongly suggests that electrification, without any changes in VMT, does, in fact, result in near-total decarbonization:

https://www.climatesolutions.org/sites/default/files/2022-05/Transpo%20Decarb%20May%202022%20web%20.pdf

So-called proponents of “environmentalism” do a huge disservice to their movement by claiming that this is not the case and de-emphasizing evidence-based arguments for why an SUV/personal-truck-centric transportation system is a fundamentally immoral societal choice*. The negative externalities of a continuation of USAnian extractive (and imperialist) capitalism require ever increasing inequality in the USA and terrible suffering in less wealthy nations (as the USA’s resources are wasted on Fordist ecofascism).

*USAnian environmentalists are deathly afraid of provoking “guilt” and this hamstrings any attempt at evidence-based arguments for decarbonization.

The report you shared is big on rhetoric and short of evidence. For example, the claim:

just isn’t justified in the report. This claim seems to underlie much of the “kill fossil fuels” movement, yet I’ve not seen one authoritative report showing HOW it can be done.

Sigh.

The full report has far more details on the modeling:

https://www.climatesolutions.org/sites/default/files/2021-12/White%20paper%20final.pdf

Ironically, this is also the report that bike portland has frequently cited and that “environmentalists” often use to falsely claim that reducing VMT travel is essential for transportation decarbonization.

The big caveat emptor with that report is that it’s only considering tailpipe emissions and not lifecycle emissions.

See Blumdrew’s excellent response to “Fred” below.

(It’s kind of sad that this is even under debate at this point in time.)

His response is great, and also doesn’t tackle lifecycle emissions. We’re not just talking about how the electricity is generated, we’re talking about the emissions involved in sourcing raw materials and in production. For a very clean energy mix, life cycle emissions of an EV can be ~25% of an ICE vehicle, which is great, but also insufficient. As we transition to EVs we ALSO need people to replace their ICE vehicles with non-cars a pretty significant scale.

I agree.

I would say that the quote there is saying EV adoption won’t do anything to reduce VMT, which is true. And the paper you reference there does in fact recommend a VMT reduction in tandem with electrification.

ODOT claiming that they somehow have no way to reduce VMT is the “intentionally obtuse” part of this discussion. Induced demand and traffic dynamics have been well-known phenomena for the better part of 100 years. Transportation “experts” who peddle road expansions without properly informing the public on the actual benefits are the issue here.

Unlike cortright, they have a nuanced recommendation, rooted in evidence.

From my perspective these insipid debates about VMT are, like carbon taxes — more kicking the ecocidal can down the road. IMO, only moral approach to low-occupancy transportation is to use harsh transformational regulation to ensure that motorized couches become a niche form of transportation.

“Motorized couches” is my phrase of the week!

I’m not sure what your beef is with Cortright here – you are claiming he is saying something that he is not saying. He is quoted as saying that EVs will not reduce VMT (in and of themselves) – which is a true thing to say, even rooted in evidence.

ODOT does have ways to reduce VMT. They aren’t interested in using them, but congestion pricing and freeway removal both would immediately reduce VMT – and would thus lower emissions. Evidently, tolling previously free roads is one of the least popular things you can do. And freeway removal is apostasy, so it’s not looking great for Oregon on that front either.

Who would be administering a harsh transformational regulation ensuring SOVs are a thing of the past? Likely ODOT would. And if men like Breyer and Strickland continue to lead at ODOT, that will never happen. It would be thrown into the “Urban Mobility Department” while the “real men” focus on the “real problems” like how to move a few thousand more cars per day the Rose Quarter.

Great article! One sentence to fix;

The look CASTS doubt (“look” is your subject, “casts” is your verb). Thanks. And please delete this comment once you’ve fixed it.

ODOT is loath to admit that they conduct social engineering through the infrastructure they provide. They claim the opposite but their infrastructure shapes behavior. There is no visionary in ODOT with a vision, goals and action plan for a sustainable future. Meanwhile half of Oregon wants to join Idaho, ignore climate change and turn back the calendar to 1960. No wonder youth despair for their future.

Only 10% of Oregon’s population is in counties that voted to join Idaho. Not all of them are registered to vote and not all of them voted to join Idaho. Since it’s never going to happen I’m not going to bother looking up the actual voter results for each county but lets say at best 5-7% of Oregonians support leaving the state. I would guess a slightly higher amount statewide would ignore climate change but even less would want to be in 1960 again. I mean how would they post mean things on Facebook?

To my eye it looks close to half of the landmass of Oregon has voted to join Idaho. I agree with you that the actual people numbers are not even close to 50%, but the concentration along a small part of the I5 corridor is kind of the problem.

https://www.opb.org/article/2022/11/09/greater-idaho-ballot-measures-pass-two-more-oregon-counties/

While it could be argued that land ought to have more rights than are currently recognized, land does not and cannot vote.

Absolutely true, just providing some context for how I understood Granpa to say “half of Oregon”.

What is this fixation on EVs as “zero-emission vehicles” that will save us from catastrophe?

Just this morning I saw a Trimet bus with a big “ZERO-EMISSIONS VEHICLE” label stamped on the side.

NO! – you are a DISPLACED-EMISSIONS VEHICLE. The only difference between a regular diesel Trimet bus and an electric one is the location of the fossil fuel powering each one: for the diesel it’s in the bus’s powertrain; for the EV it’s upstream at a power plant that is burning coal or natural gas to generate electricity (also a tiny percentage currently being generated by wind and solar). AND the fossil fuel powering the EV is actually *less* efficient than the diesel powering the other bus b/c it’s so far downstream and energy is always lost in conversion. But people get to say their EVs are clean so I guess that’s the important thing.

I like this line – displaced emissions. Ideally the emissions happen much farther away from human lungs, but they still have to be acknowledged and ultimately avoided to get to a livable future.

Someone has to breathe in the emissions and someone has to suffer for the energy extraction. Either the society driving the vehicles or the society unlucky enough to be near the power plant. Either the society using the resources or the society unlucky enough to be colonized for its lithium or oil. I have never understood the well off people who decry colonization, but refuse to have energy extraction anywhere near themselves and don’t realize they are pushing health problems onto others much in the way of colonialism.

Got a life-cycle analysis to back up this utterly ridiculous and anti-electrification claim?

Here you go:

https://www.enerdynamics.com/Energy-Currents_Blog/How-Much-Primary-Energy-Is-Wasted-Before-Consumers-See-Value-from-Electricity.aspx

This link does not support your ridiculous contention because diesel engines have an efficiency in the 40% range (with a theoretical limit of ~55%).

https://www.jstor.org/stable/26649163

Electric motors are an order of magnitude more energy efficient than gas internal combustion engines. Even accounting for transmission, battery, and other loses electric motors still come out ahead. Additionally, the PNW has a (relatively) clean power grid owing to historic investments in hydroelectric – currently about 39% statewide (vs 26% for coal and 21% for natural gas). Wind, Nuclear and Solar combine for around 12%.

EV cars are functionally infinitely cleaner post-production. Even the most absurd EVs have lifecycle emissions lower than the majority of ICE cars.

The issue here is that ODOT views higher VMT only as bad because of emissions – not because of the myriad of other negative externalities. They are still nakedly endorsing automobile propaganda from the 1930s. Lee Breyer is talking like a Robert Moses acolyte if he thinks ODOT has no way to reduce VMT. Maybe next he will be campaigning on building the Oyster Bay Bridge to reduce traffic on the Throgs Neck.

Many climate movement types also sound like this. (I follow many of these climate movement folks on social media and they invariably admit to owning ICE SUVs or trucks.)

Right, which is unfortunate. The negative externalities of driving do not end at the tailpipe, and I think it would be nice to see more of an emphasis on that from advocates.

The electric motor is itself more efficient, but the TRANSMISSION of fossil-fuel-generated electricity is the really wasteful part.

The point is that if you are going to use fossil fuel to generate motive power, you are actually better off burning it in an ICE than burning it in a power plant and sending it over many wires to reach an outlet that will charge an EV.

Yes, electricity *CAN* be produced from renewable (non-fossil-fuel) sources, but so far we haven’t figured out how to do it on the scale that would be required to fuel the number of EVs that would be needed to replace all of the ICE-powered cars and trucks.

According to the EIA, about 11% of generated power in Oregon doesn’t reach consumers (this isn’t all transmission related loses I would think, and could be loss related to peak-matching or something like that – again, not an electrical engineer).

Even if you completely ignore how much it costs to extract, refine, and transport gas to the pump, EVs still come out ahead.

Coupled with the 11% production-consumption loss, there is about a 15% loss between the wall and the battery. And an electric motor has about 85% efficiency. So using 500 kWh of an EV car battery means that about 775 kWh needed to be produced on the grid, for a total efficiency of around 65%. An internal combustion engine has a maximum theoretical efficiency of around 62% to 66% (with compression ratios ranging between 20 and 30 – far higher than a typical consumer engine). In reality, a typical gas car is in the neighborhood of 30% – and this doesn’t account for the cost to get the gas in the tank. I am ignoring losses in the transmission of the car on purpose, but since electric motors are less complex I think they usually have more efficient transmissions as well.

It’s more efficient to burn oil (or coal, or natural gas) at a power plant, transmit it through the electric grid, charge an EV battery and take an EV out for a spin than it is to just pump oil at a gas station for an internal combustion engine.

I personally don’t consider hydroelectricity clean. It’s damaged/destroyed ways of life both indigenous human and fish simply because we as a people refuse to pay upfront for the energy we use. Like mining and mineral extraction we always want someone else to suffer the effects while we do what we want without guilt.

https://www.opb.org/article/2022/08/04/bonneville-power-administration-columbia-river-dams-salmon-recovery-spending-tribes/

https://www.nwcouncil.org/reports/columbia-river-history/damsimpacts/

I am well aware of the environmental and cultural destruction associated with dam building. But the dams have been built, and the electricity they produce now no* emissions. That’s a good thing, although I wouldn’t be opposed to some dam removal (particularly the Dallas dam which inundates Celilo Falls).

*if we want to be technical, it does cost money/emissions to service the moving parts of the powerhouses. But that’s true of all green power sources

I would say that emissions alone aren’t enough of a metric to label something green or clean. The damage the dams do is ongoing and would cease if they were no longer there providing so called clean energy to run all our devices/cars. Just saying the damage they cause is okay seems too much like saying we should leave ICE vehicles alone because the fueling infrastructure has already been built.

That’s fair. I use green as a short-hand for “no additional carbon emissions at point of generation”. I’m not intending to say there are no trade-offs, there are trade-offs for all electrical power sources.

Environmental (and cultural) damage of the Columbia River dams should be judged on a case-by-case basis. The reason I singled out the Dalles Dam for removal is because it think it drowned the most important Native cultural site in the entire Pacific Northwest. That damage is 100% worth undoing, plus it provides a relatively small amount of electric power compared to the basin at large. Also, once one of the Columbia-Snake dams is removed, the impetus for keeping them all to allow for barging would be significantly reduced.

Further upstream in BC, I think removing the Mica Dam to restore the historic flow characteristics of the river would be another good step too. I think Grand Coulee probably would be one that stays – it’s too important for both irrigated ag (which is not worth saving in my opinion – but easy for me to say since I’m not a farmer) and for hydro generation. Maybe Grand Coulee would be the head of “salmon navigation” on the river, and most of the downstream dams could be removed. Maybe some of the downstream ones could stay, if they have sufficient fish passage abilities (and the river is still fast enough to make salmon well equipped to survive).

It really makes me angry that many USAnian environmentalists don’t see decreasing green house gas emissions (and the interlinked issue of agricultural land use) as an overwhelming global priority. In my experience, many USAnian environmentalists have a laser focus on small issues/campains in their backyard (localism, NIMBYism) and don’t seem to care much about how the continuing GHG emissions and consumption (land-use) of rich nations is creating a living hell for people in the global south.

Big hat, no cattle.

I wish ODOT spent half as many resources trying to put together projects that achieved their stated goals rather than branding, and rebranding (looking at you CRC/IBR and I-5 RQ), and marketing every project and policy as being simultaneously the solution to a long running problem while simultaneously locking us into the next project that is needed to solve the exact same problem.

The word “sufficient” is missing from this statement. Remember 3-5% of project spend was too much to dedicate when the issue came up last session. Though it wouldn’t be as optimistic to say that ODOT is consistently underfunding investments in bike and pedestrian infrastructure, in part, necessitating the closure of 181 crossings to comply with ADA, though they’re underfunding by slightly less now. It also completely ignores the rise in traffic-related deaths which discourage usage of facilities by people who are concerned about making it to their destination alive and uninjured.

ODOT really likes taking credit for existing trends in their projects as well, projecting that the change is due to a project rather than something unrelated. The site seemed like propaganda rather than a clear eyed assessment of where things are and need to be. The only thing ODOT is doing to discourage driving right now involves tolling and the only reason why that is moving forward is because it’ll allow ODOT to keep building more car-centric projects with another revenue stream.

ODOT is a bad faith actor that is actually getting decently in greenwashing their motor vehicle projects. No one should take anything they say or do seriously.

Source: just trust me bro

Being critical of ODOT is like beating an old horse trying to make it run faster. ODOT is a top notch engineering organization with a culture of building highways to move as many cars as possible for their budget as safe as possible (safe for drivers). That has been their mission for decades. The only way they are going to change is through strong leadership from those they answer to – the state legislature. Energy spent beating on ODOT is better spent on the elected officials they answer to. The sad fact is they answer to a lot of elected officials who never walk, or drive, or take transit anywhere, and view all three as something to be avoided. I think ODOT is doing a great job and Chis Strickler is an excellent Director. They just need to be directed to change the nature of their work. Like all engineers, they are no good at sales, which is why they get beat on by those victimized by a pitiful transportation system. The more you beat on them, the more they are going to rely upon slick marketers and PR folks, which is exactly what they are doing with the IBR and Rose Quarter. Unlike the ODOT engineers, the marketers and PR folks are profit-driven contractors and not held back by a culture of public service, which means the more you empower them, the harder it is going to change ODOT.

Laughable to think that somehow ODOT has no influence on transportation policy in the state, and that they just “do what the legislature tells them”. They are a highway-first, transit-last org. There is no way they will just “change the nature of their work” – even if they are explicitly directed to by the legislature.

On the RQ project, the legislature directed them to “ease congestion” and they chose a freeway expansion. Any organization that is still widening freeways to “ease congestion” is not one that takes anything other than road building in and of itself seriously. There is almost a century worth of evidence showing that wider roads don’t ease congestion, yet Strickler thinks that somehow this project is different since they are labeling the new lanes as “auxiliary”. Next up, a new wider bridge over the Columbia to ease congestion on the old one which certainly will be just as congested as the old one. In NYC, the Tribourough (RFK) bridge was built to reduce congestion on the Queensboro – but it actually increased it. The Bronx-Whitestone was constructed to reduce congestion on the Tribourough – but increased it. The Throgs Neck Bridge was constructed to reduce congestion on the Bronx-Whitestone – but increased it. And the only thing that stopped Robert Moses from building the Oyster Bay – Rye Bridge (to “reduce congestion” on the Throgs Neck) was Nelson Rockafeller stripping him of his power by creating the MTA. If Kris Strickler is aware of the history of induced demand, he doesn’t really act like it.

Will our governor attempt to reduce the power of ODOT in transportation related projects state-wide? Seems unlikely to me. But agencies never change their ways when the same people have functionally the same power. Which is part of why ODOT still functions mostly as the State Highway Department.

The legislature directed bonding specifically to the I5 RQ freeway expansion. Moreover, the democratic legislature gave a crystal clear indication of its legislative intent when it discussed and passed HB 2001.

It really would be a mistake to let the legislature off the hook here. They have been very clear in what they’ve been asking for, and they’re the ones with the power to change ODOT’s direction.

Laughable to think you can change a rigid bureaucracy like ODOT without some serious heat from their elected officials. Cryable to think that people think it will come from ODOT without that heat.