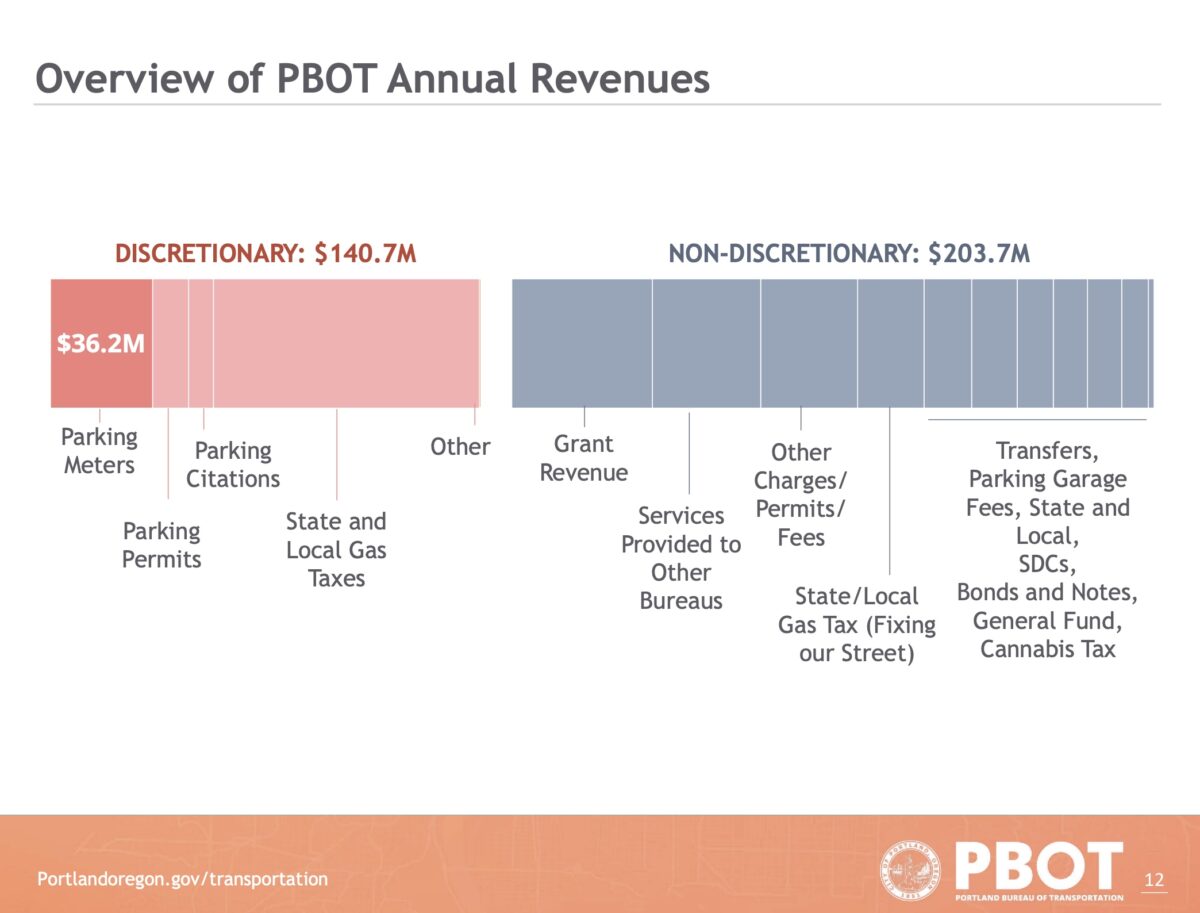

The simple act of parking a car plays an outsized role in budget and policymaking at the Portland Bureau of Transportation. Parking-related fees make up a whopping one-third (around $50 million) of PBOT’s total annual discretionary revenue. That’s a problem for an already cash-strapped bureau that has adopted many policy goals that require them to reduce the amount of cars in the city.

At City Council Wednesday (9/22), commissioners will hear a presentation from PBOT about that parking meter revenue. PBOT will ask them to accept their Net Meter Revenue Policy Report that was made final earlier this month. “Net meter revenue” is the amount of funding that flows into city coffers from parking fees after they’ve done required maintenance on parking meters and paid staff to operate and maintain the system. The recommendations in the report are the product of a process that began in early 2019 with a goal to review Portland’s transportation planning rule TRN 3.102 (“Parking Meter Revenue Allocation Policy”) that was passed way back in 1996.

Priorities and principles at PBOT have changed a lot in 22 years, so many felt it might be time to change how parking meter revenue is doled out and re-assess its role in city decisionmaking. With millions of dollars in revenue at stake, and a chance to influence the number of driving trips (which play a critical role in our fight against climate change), this wonky sounding report has far-reaching implications.

Advertisement

“This amendment also offers an opportunity for Portland to make a clear statement of where SOV [single-occupancy vehicle] trips fall on our transportation mode hierarchy.”

— André Lightsey-Walker, The Street Trust

The Street Trust thinks the recommendations in the report left out one key opportunity. In a letter to Mayor Ted Wheeler and the commissioners they request an amendment that would, “Ensure the Net Meter Revenue policy update directly supports a wider array of Portland’s street users”. Specifically, they want some of the net meter revenue proceeds to fund free transit for low-income Portlanders who live in metered districts (one of the stipulations in the current rule is that 51% of meter funds are invested back in the district they’re gathered in).

By providing low-income residents of these districts with free transit we will be able to support Portland’s equity and climate goals,” reads the letter written by The Street Trust Policy Transformation Manager André Lightsey-Walker. “This amendment also offers an opportunity for Portland to make a clear statement of where SOV [single-occupancy vehicle] trips fall on our transportation mode hierarchy.”

Other advocates had more critical words to share about the report.

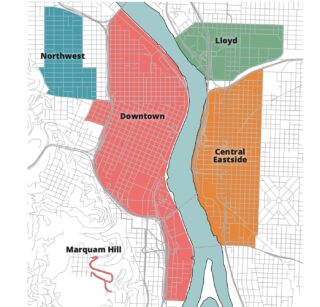

Before I get into those, it’s important to understand that Portland has five parking meter districts (above): Downtown, Northwest, Lloyd, Central Eastside, Marquam Hill. The Downtown District was created in 1938, accounts for about $30 million of the $36 million in parking meter revenue collected by PBOT each year, and is not beholden to the 1996 law referenced above. That means that big chunk of revenue doesn’t have the same strings and accountability as revenue from the newer districts. The revenue goes into the General Fund and advocates aren’t able to easily direct it to projects and programs that would reduce car trips.

Through this policy review process, PBOT had a huge opportunity to change these rules. Unfortunately they didn’t.

“This policy proposal maintains the status quo [downtown], in regards to allocation of net meter revenue,” the report reads. “It is recommended the downtown parking meter district continue to be exempt from the Net Meter Revenue Policy.”

That irked at least one source who contacted us about the report. “If PBOT’s top two priorities per the Strategic Plan are confronting racial equity and climate change, this policy is wrong on both fronts by continuing to enrich the status quo of private business groups, while not providing TDM [transportation demand management] funds to the densest neighborhoods, where TDM options and management are needed most.”

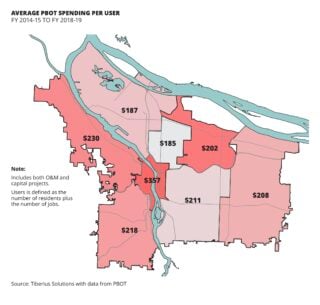

In the report PBOT says an analysis of per capita transportation spending (above) shows the central city already receives ample investment — about 1.5 times more than any other neighborhood coalition area. PBOT said “conversations with downtown stakeholders supported this conclusion”.

At least one downtown stakeholder disagrees. A letter sent to City Council members from the Pearl District Neighborhood Association dated September 21st expressed opposition to the report, “Because it does not go far enough in serving the multimodal transportation needs of the neighborhoods located in the downtown meter district, including its sizable number of low-income residents and employees.”

The PDNA wants the Downtown Meter District to be in the same boat as the other four district when it comes to rules governing how meter revenue is spent. In particular, they want downtown neighborhoods to do more to help manage transportation demand (read: fewer driving trips) and improve biking and walking infrastructure through things like the Central City in Motion plan, better TriMet bus service, and investment in PBOT’s successful “Transportation Wallet” program that provides transit and Biketown passes at a heavily reduced rate to district residents.

“Instead of using this process to harmonize parking management practices across the city and place the Downtown Meter District in parity with newer parking districts, PBOT has reneged on its commitment and chosen instead to maintain a two-tiered system whereas downtown neighborhoods are punished simply for being first,” the PDNA letter states.

The PDNA also chides the report for not creating new parking districts on eastside commercial corridors like 28th Avenue, Hawthorne, Mississippi, Alberta, and Hawthorne. “We are sincerely disappointed by the lack of tangible solutions documented in this effort,” says the PDNA.

You can watch the council presentation and discussion on the City of Portland YouTube channel.

— Jonathan Maus: (503) 706-8804, @jonathan_maus on Twitter and jonathan@bikeportland.org

— Get our headlines delivered to your inbox.

— Support this independent community media outlet with a one-time contribution or monthly subscription.

Thanks for reading.

BikePortland has served this community with independent community journalism since 2005. We rely on subscriptions from readers like you to survive. Your financial support is vital in keeping this valuable resource alive and well.

Please subscribe today to strengthen and expand our work.

What is the TST proposing the city not do in order to pay for transit passes? Let’s have that conversation directly rather than pretending it’s about meter revenue. If meters no longer paid for PBOT, something in the city’s budget would need to be cut to compensate. Couching this as “meter revenue” is using symbolism to avoid the difficult conversation.

And if this is targeted at folks living adjacent to downtown, would they use transit enough to make transit passes at all cost efficient? Would this offset much driving? (or any at all?)

I’d like to see a proposal that makes the case directly that funding transit passes for inner city folks is an effective use of money to reduce driving and/or carbon emissions. If it is, let’s fund it without the budgeting gimmicks.

The reason it makes sense to use some of this money for transit subsidies is that the city goals are to reduce car trips but a major funding source for the city is car trips to/from downtown. By using that money to further reduce car traffic we are allocating it to a purpose that will no longer need funding when the funding source runs out! When there’s no more car trips, we don’t need to fund the TDM!

I would not do exactly what TST suggests here, but they are on the right track. I would include low-income downtown WORKERS as well and I would fund an expansion (perhaps city-wide) of the Golden Transportation Wallet.

Furthermore, additional pricing strategies are coming, but the city is very sensitive to the impact they will have on low income households. Using meter money to offset those costs will allow for more aggressive implementation of those strategies.

You too are avoiding the key questions, which is not which particular dollars should fund bus passes, but rather 1) is funding passes to people living or working downtown an efficient way to reduce CO2 emissions? (this requires projecting what it will cost, how many/which trips will move towards more efficient modes, and how that compares to potential alternate strategies); and 2) where will the money ultimately come from, i.e. will we raise taxes to backfill PBOT’s budget, or will we cut something that’s currently funded?

With good answers to those questions in hand, then we can talk about the budget mechanics.

Look, if I had my way I’d send a couple hundred dollars twice a year to low-income households as a “transportation fee prebate” that they could use to offset meter costs, permits, tolls, parking fees, gas tax, etc. And then I’d jack up the price of driving via gas tax increases, parking fees, and tolls. Low income people who drive would have mitigation, but others would choose to drive less and use the cash for other things. Some middle-upper income people would drive less or change behavior to avoid the fees, but we’d raise more money that we could apply to multimodal projects and transit subsidy/expansion.

In the meantime, the city would likely only pay for estimated usage of transit by the people they are giving it too, just like with the youth pass. So if low income people didn’t take advantage, we would know and could try something else.

Human behavior can’t be predicted precisely enough to give a remotely objective answer to your second question. A study conducted by an organization with a vested interest in maintaining auto dominance would easily make the case that transit use would not increase, and a study by a more progressive, optimistic firm could easily “prove” the opposite.

More parking districts, please. A lot of money is being left on the table.

The last time I saw a report on the Central Eastside budget, there was something like $1,400,000. NET parking meter revenue for ONE year – this was the cut for CE Council to decide what to do with [I believe that discretionary spending does require City approval??].

One year, they bought a brand new shuttle van and hired people to drive it around CEID … mostly empty. Trying to imagine what else they did with all that money.

There is something perverse about PBOT being so dependent on parking proceeds, when reducing driving is stated policy – which is sorely needed. I suppose this is at least partly why PBOT is so reluctant to remove parking … that, and screaming neighbors to be sure.

Agreed. No doubt PBOT’s budget needs to be decoupled from parking revenue much like utilities and electricity production/consumption. Too much opportunity for perverse incentives. This isn’t a charge of corruption against PBOT employees, rather, good policy to align incentives

THAT is a plan that prioritizes community justice and climate change.

I’m on board with most of this EXCEPT I would not have a sliding scale permit. Better would be to provide a “prebate” in the form of periodic checks sent to low-income qualified households (for example, households receiving WIC) to offset the cost of permits/meters/etc. A sliding scale only benefits low income households with cars, a truly equitable benefit is given to all low-income households and they can spend it as they see fit.

Excellent points!

I’ve often thought that Portland should implement an overnight parking permit system, similar to what other large cities in the midwest and east coast have done (Milwaukee Wisc is one of them). Different than just a per-car “wheel tax” like Chicago has, essentially between 2 or 3AM to the morning unless you have a permit you can’t park on city streets overnight. Now it’s all done online using the license plate just like the pay by mail toll systems. Obviously you can’t enforce this city wide every night so it’s usually done by random patrol throughout neighborhoods. This would be a good way to raise parking revenue, encourage people to not park on the streets, and frankly provide another enforcement mechanism to get derelict and burnt out vehicles off the streets.