The idea that cars = freedom is a pervasive American myth. The truth is that the rise of the automobile — and rampant illegal behaviors that have always accompanied it — helped give rise to an armed street security force that too often acts as judge, jury, and executioner.

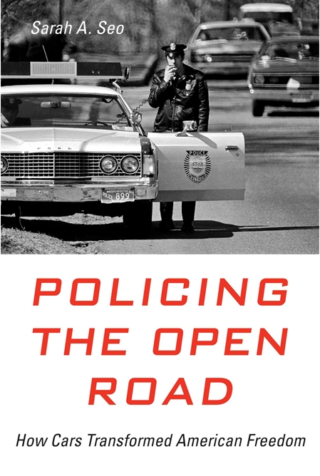

Sarah Seo’s book, Policing the Open Road (2019, Harvard University Press), is a cultural history of how we arrived at the system we have today, told through the lens of jurisprudence and law enforcement. It’s about how governments scrambled to regulate the automobile revolution, about the overwhelming volume of laws they created, the need to make them uniform, and how the process of creating the rules of the road, and enforcing them, transformed America’s concept of privacy and freedom.

Take, for example, driving on the right side of the road. After being ticketed by a state trooper for driving on the wrong side, a man hired a lawyer who argued that there was no “wrong” side, that the law merely stated that you had to pull to the right when you met an oncoming car. That man had his day in court and won. It seems that proto-advisory shoulders were the law of the land in early 20th-century Iowa.

Advertisement

The hiring of a lawyer tips-off one of Seo’s main themes: Before the automobile, the white upper classes did not interact with law enforcement. That changed with the advent of traffic laws. “Law-abiding citizens were apparently incapable of governing themselves on the road,” and they didn’t like being policed. They hired lawyers, complained, pushed-back and boasted of traffic violations at cocktail parties. “Maintaining the public’s support while at the same time managing traffic constituted ‘one of the police department’s most serious problems.’”

“Black citizens had to anticipate the possibility of encountering an abusive officer.”

Having to enforce laws upon the upper classes is what led to the professionalization of the police — the uniforms, the marked cars, the hiring standards. It led to criminalizing disobedience and the ticketing system. The growth of automobility served as “the justification and the modality for scaling up police law enforcement as a method for governing all American society.”

Prohibition and the need to search and seize, and later the War on Drugs, brought this juggernaut of policing into conflict with the Fourth Amendment’s constitutional protection against search and seizure. A large part of Seo’s book is about the path of case law trying to reconcile the novelty of a private object (the car) operating in the public space (the road), and ultimately the question of what is private and what is public. This legacy has left us with concepts such as reasonableness, probable cause, and a vast expansion of police officer discretion.

Advertisement

Seo doesn’t mention Black people until over half way through the book. That surprised me because her lede into the podcast interview I listened to prior to reading the book was the death of Sandra Bland, a 28-year-old Black woman who died while in police custody in Texas after being pulled over for a minor traffic violation. On the podcast, Seo noted that every step in Bland’s demise had involved a car and the police. Seo’s decision to leave out swaths of society in the first half of the book can be justified in that the transformation of jurisprudence she discusses was driven by middle-class white people in cars.

For me, that focus had the literary effect of giving the book the inevitability of a tragedy. It’s with dread one reads that “by directing officers to be considerate of the general motoring public but not of the criminally suspect, the mandate of courtesy implicitly acknowledged the police’s increasingly discretionary authority to discern the difference between the two.” We know which people will be considered criminally suspect — immigrants, the poor, Blacks. We know where this is headed.

This drumbeat builds to the second half of the book which seamlessly interweaves the racial and social issues of policing within the legal system. It’s in the final chapters that Seo discusses stop and frisk, the difference between arbitrary versus discriminatory policing, the targeting of civil rights activists for traffic stops, Driving While Black and the reality that “Black citizens had to anticipate the possibility of encountering an abusive officer.”

Last Friday, Seo wrote an op-ed for the New York Times advocating for automated speed cameras as a way of reducing police encounters and avoiding selective or discriminatory stops. She also mentioned better engineering of roads, noting that “the people who figured out how to draw a line down the middle of the road did more to enforce the the keep-to-the-right rule than anything the police could do.”

Policing the Open Road is the rare book which changes the way you look at the world. I found it unexpectedly moving and strongly recommend it, with the caveat that the second half will be tough going for readers who are not interested in the logic of case law and jurisprudence.

— Lisa Caballero, lisacaballero853@gmail.com

— Get our headlines delivered to your inbox.

— Support this independent community media outlet with a one-time contribution or monthly subscription.

Thanks for reading.

BikePortland has served this community with independent community journalism since 2005. We rely on subscriptions from readers like you to survive. Your financial support is vital in keeping this valuable resource alive and well.

Please subscribe today to strengthen and expand our work.

From the article:

“She also mentioned better engineering of roads, noting that “the people who figured out how to draw a line down the middle of the road did more to enforce the the keep-to-the-right rule than anything the police could do.”

Could this design principle be extended to enable cars to self-enforce driver behavior? What if the car knew the local speed limit and could not exceed a certain maximum speed? What if all cars required authentication, so the driver at the time of an infraction or crash were known? What if it could sense the behavior of a drunk or distracted driver? etc.

The history of policing she describes reveals the lie at the heart of the myth of driving as pure freedom. Would reducing the car’s ability to be operated unsafely actually increase that freedom, especially that of marginalized groups?

Jonno, I agree. I’m out of town writing on a phone, so can’t easily write as much as I’d like to. But, take the Tesla, it knows where it is, what speed its going, what the posted speed is, what time of day it is and the weather.

So, how did a driver of a Tesla manage to plow into a tree near Corvallis going 100 mph? Why is that even possible? The crash was so dramatic the NTSA even used a photo of it in its most recent report.

Thank you for the comment.

The model S in Ludicrous mode produces 1020 HP, a top speed of 200 mph and only takes 1.99 seconds to go from 0 to 60 mph. So plowing into a tree at 100 mph is easy. 3 days ago two people died when there tesla went off the road in a corner and hit a tree. The fire took 4 hours and 30,000 gallons of water to put out. One person was found in the passenger seat the other was found in the back seat. Speculation is the car was on auto pilot when it crashed.

This is a timely book (and book review) b/c I’ve been thinking a lot about the forces that animate us as we are driving, or cycling, or running, or walking.

I’ve decided that much of the animating force behind driving a car in the US derives from irresponsibility, which is what people really mean when they use the word “freedom.” From the earliest ages, children in the US see driving a car not as a privilege laden with responsibility, but as a ticket to freedom, meaning irresponsibility – go wherever you want, whenever you want, as fast as you want (til someone tells you you can’t). Look at how young drivers (ages 16 to 21) approach driving: it’s the way to get away from parents and teachers and other authority figures. Put down that sunroof and blast the music and open a beer! It’s road-trip time!

Everything in popular culture – advertising, TV shows, movies, novels, you name it – reinforces the idea that driving is about being irresponsible, i.e. “free.”

I think about this issue every time I’m walking or riding my bike and a car passes me with music blaring so loudly, there’s no way the driver can be aware of anything except what he can hear inside the car. Same for the car passing me 10-15 mph above the speed limit, with the driver holding her cellphone.

Anyone who spends any time on the road sees constant examples of irresponsibility and can’t help wondering why more isn’t done to stop it.

If I walk up to you and threaten to maim or kill you with a deadly weapon if you don’t immediately get out of my way, that’s menacing and I could go to jail for years. If I drive up to you and do the same, I likely wouldn’t even get a ticket for failure to yield.

I would very much encourage the idea of engineering roads to encourage safe use of those roads by motorists, cyclists and pedestrians.

I was recounting at a social gathering recently that I grew up in Canberra in Australia. Canberra’s streetscape was largely laid out from the 1950’s, by which time most households in Australia either had a motor vehicle or were anticipating acquiring one in the near future. Canberra’s designers deliberately chose not to use a grid system. There are winding streets, crescents and cul-de-sacs. However, these winding streets are also interlaced with a system of pedestrian/cycle paths that the distance to walk or cycle from my home to the local shops was 900 meters, but the distance to drive was 1,300 meters. Similarly, the walk/cycle route to my school was largely off-road and 2.8 km, but the drive was 3.4 km (my parents never drove us to school, that’s what buses and bicycles were for).

Now, in Canberra, it was rare (though not unheard of) for people to speed along the narrow residential streets, that was mostly confined to the wider connecting/arterial streets. Also, the legislatures in Australia have established a system of automated enforcement (speed/red light cameras) that is legal within their constitutional arrangements. Drivers are rarely arrested at traffic stops (only for DWI offenses or driving in a manner/at a speed dangerous to the general public). None of this is to say that Canberra is perfect for road users – it’s not, but it’s better than many places in the USA.

We, in the USA, can learn a lot of lessons from our friends in other countries, if we’ll take of our nationalist blinders and look.

I spent two months in Canberra in the late 90s. I fondly remember bike rides around the lake and easily being able to walk w our toddler to get to the bus stop which took us to his daycare. No car needed except to leave town. I think my husband got every by bike. I’ve got a soft spot for the place.