(Photo: Jonathan Maus/BikePortland)

Discussions of how gentrification and displacement are tied to transportation is something we’ve covered at length here on BikePortland over the years. But what’s missing from our understanding of these issues are perspectives from Black Portlanders who’ve been directly impacted by being uprooted from their close-in neighborhoods and living in a place that’s far less easy to get around in.

Research just published by former Portland resident Steven Howland gives us new insights about how severe demographic changes in north Portland have taken a toll on Black lives. Howland’s research was done as part of his pursuit of a Ph.D. of Philosophy in Urban Studies from Portland State University. His dissertation, ‘I Should Have Moved Somewhere Else’: The Impacts of Gentrification on Transportation and Social Support for Black Working-Poor Families in Portland, OR, was funded by the National Institute for Transportation and Communities and has been published by the Transportation Research and Education Center at PSU.

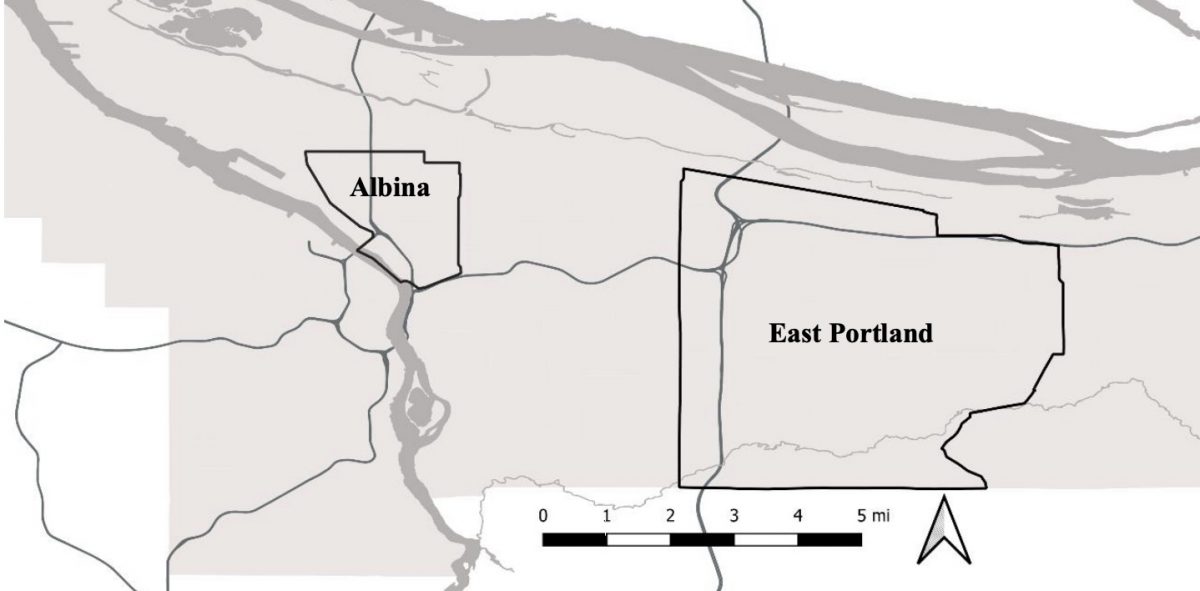

In 2017 Howland interviewed 27 working-age Black people with children — half of them lived in Albina and the other half had moved from there to east Portland. In addition to asking about mode preferences, Howland asked questions about the social impacts of being uprooted from Albina (an older, more dense and walkable neighborhood) to east Portland (a place with more arterial streets, and longer distances between destinations).

What Howland found was striking and should create even more urgency to make transit, walking and biking compete better against driving — and to prevent displacement in the first place.

Howland’s interviews reveal the human side of the challenges people face when they move from close-in to suburban neighborhoods. “I found that people in Albina were better resourced, on average, to accomplish their daily life maintenance,” he wrote. “Through easier transportation (including a higher rate of car ownership), better and stronger social support networks, and a higher density of nearby destinations, Albina residents could get around faster, easier, and accomplish more in a day. East Portlanders struggled far more. Clustering of destinations around the western edge of East Portland put those destinations out of reach for most of them.”

Here’s more from Howland:

“Given the level of disadvantage facing low-income Black populations based on where they can live and the resources available to them, mode choice has a drastic impact on their life outcomes… For low-income Black populations, the effects of racism, segregation, and sustained material hardship prevents their full participation in society. A society, which through suburbanization and orienting life and policy around the automobile assumes people will get around by a car and can travel long distances for their everyday life. They are thereby socially excluded from society, but we have limited knowledge as to the way this manifest in the lives of low-income Black populations or the effects it has on their life.”

Advertisement

Despite strides Portland is making with transit, bicycling and walking infrastructure, they still lag far behind driving in perceptions of safety and desirability.

“We got this busy intersection here and these other cars that be speeding down the damn street, a residential street. They be doing 50 down a 25mph. Don’t ride it out here. I don’t trust it out here.”

— East Portland father

When it comes to using TriMet, many of Howland’s interviewees expressed frustrations with reliability and a fear of other riders: “This was spurred in part by the racially-motivated murders on MAX, but mostly because of their encounters with homeless people and people with untreated mental illnesses which also spilled over into overt racist acts against them or their children.”

His report includes harrowing accounts of walking in east Portland. “Yea, the drivers. You never know with the drivers. Like at night you really need them reflectors, because they drive like crazy down 162nd. It’s bad,” remarked one woman. Another bemoaned the lack of safe crossings: “There’s not that many crosswalks. I’m glad they just made one at 165th where I live. But crossing the street at night, it’s like you either have to walk all the way to 162nd or to 174th to properly cross the street. But I end up crossing the middle of the block. And people aren’t following the speed limits. Or they’re always pulling out the bar drunk or something.”

Despite bad reviews of TriMet and fears around walking, bicycling barely registered as a viable mode among the interviewees. Only three of the 27 people Howland spoke with rode a bike — and none of them did so on streets due to safety concerns.

“I’m not doing that. Sweating. People looking at me, I’m sweating, pedal pedal pedal. You know. Before it gets to that point, I would rather just walk to my destination. Because then I’ll have my purse with me where I’ll have a bottle of water or something. But yea I’m not biking it,” said one woman.

One father he interviewed in east Portland was too afraid to let his kids bike near their home so he’d load them in his truck and only let the kids ride when he visited family in Albina. “Where we stay at it’s real crazy,” the man said. “We tell ’em ride [bikes] at your grandma’s [who lives in

Albina] because the area over there is safer. We got this busy intersection here and these other cars that be speeding down the damn street, a residential street. They be doing 50 down a 25mph. Don’t ride it out here. I don’t trust it out here.”

Howland’s research comes in the same month that Willamette Week reported about how east of 82nd, overcrowded living conditions have contributed to COVID-19 infection spikes and fewer street trees lead to higher summer temperatures.

Whatever we’re doing to improve the lives of people who live in east Portland, we need to do more of it. Faster.

You can follow Howland on Twitter and learn more about this research on TREC’s website.

— Jonathan Maus: (503) 706-8804, @jonathan_maus on Twitter and jonathan@bikeportland.org

— Get our headlines delivered to your inbox.

— Support this independent community media outlet with a one-time contribution or monthly subscription.

Thanks for reading.

BikePortland has served this community with independent community journalism since 2005. We rely on subscriptions from readers like you to survive. Your financial support is vital in keeping this valuable resource alive and well.

Please subscribe today to strengthen and expand our work.

Re: “Only three of the 27 people Howland spoke with rode a bike on a regular basis.” That’s 11%. The city of Portland commute share was 7% at the most, in the whole city, and it’s been only 1% or 2% in East Portland. So if over 10% of Black people from Albina who have been displaced to East Portland are frequently riding bikes, that’s actually a really high number compared to their neighbors.

Sigh.

I think you’re misreading that and it might be partly my fault. I should have left the “on a regular basis” part off. If you read the report, he goes on to say that none of those three use their bikes for any utilitarian function. One rides with their kids on the 205 path, the others do it for exercise from time to time. And none of them feel safe riding in traffic so they ride on the sidewalks or on paths. And regardless of all that this is far fro ma valid sample size to draw any conclusions from… You are taking a qualitative study and trying to draw quantitative conclusions from it. I would not do that if I were you.

I read that last line in a Prince Humperdink voice.

I see Jonathan’s post, but to echo what he said:

Commuting and general bike usage are separate measures.

I’m hoping that the City will recognize that even buffered bike lanes and wider sidewalks won’t be the only fix to properly address this.

The entirety of how the city is designed after 102nd is the issue we must contend with. Post war suburban developments in a loose gridiron of auto-centric arterials have proved to be dangerous and unsustainable. In this format, the conversion to inner city densities and lifestyles in a safe, sustainable, and most importantly: equitable manner will be our biggest challenge.

Yes, I totally agree, the area west of 102nd is a total disaster, with the 200-foot blocks and the free on-street parking everywhere – an incredible waste of space devoted to the automobile, which absolutely dominates inner Portland. Whereas the area east of 102nd was developed by Multnomah County based on the best practices of the 1960s and 70s to minimize right-of-way using superblocks, ban parking on all arterial streets (a policy reversed by the City of Portland after annexation), locating parks and schools in the safest and most pedestrian-oriented center of each superblock, and making it as difficult as possible for cars to use local streets to get around. PBOT & BPS has since annexation in 1991 done everything possible to screw up this design rather than actively try to improve on it, including allowing and encouraging large apartment density zoning along the arterial streets, turning residential streets into expressways, ending the County’s program on building connecting paths and sidewalks through superblocks, and underfunding needed improvements.

When I first moved to Albina just 10 or 11 years ago, it was still essentially a food and commercial desert, with very few businesses in walking distance and many vacant lots. It certainly was not the dense urban environment we have in the neighborhood now, much of which was developed in the past decade. It was also much more dangerous for pedestrians and cyclists, in my opinion.

I am not in favor of displacing long-time residents of any neighborhood, but I think it’s fair to point out that gentrification also includes improvements to quality of life for those who remain, including the many people of color who still live on my block and in the surrounding neighborhood.

I lived over there in the early 90s. You could buy cigarettes, malt liquor, and ho hos but that’s about it.

Also this idea that Albina is some ancestral homeland of black Portland is revisionist history. This ain’t Atlanta or DC. Even when Albina was “the hood” it was 40% white and/or hispanic.

Final point, “progressive” thought then was that rather than concentrating the poor in ghettos of poverty, section 8 could be used to spread poor people out to areas with better educational opportunities. We’re nostalgic for the era of ghettos now?

A few points…

1: What if the poor people in question didn’t want or choose to be “spread out” of their convenient, familiar neighborhood and into other far-flung parts of town?

2: The people who’ve been displaced from Albina haven’t gone to “areas with better educational opportunities”. Instead, they were pushed out into areas with less resources than where they were, and meanwhile the neighborhood they left is seeing more $ flow into infrastructure, schools, etc. now that it’s in the interest of the new, white arrivals.

3: Ice Cube said “you call my neighborhood a ghetto cause it houses minorities.” Albina was more than a ghetto.

Caption under map: “In 1990 Albina was 38% Black, but by 2017 it was less than 13%. Meanwhile East Portland grew from 1.5% Black to nearly 8% in that same period.”

You are implying a geographic migration that isn’t actually supported by the data. East Portland became more black not necessarily because black people from inner Portland moved there (though obviously many did), but much more because most Somali and other African refugees were settled there (the cheapest part of town) and never lived in inner Portland. Most inner Portland blacks who moved out of Albina and other inner Portland neighborhoods left the city altogether, usually to places that are more affordable and less overtly racist.

Referring to African-Americans and immigrants from Africa with the same label obscures more than it enlightens. They are really two very different groups of people without much in common. An immigrant from Somalia and an immigrant from Myanmar may have far more in common with one another than either do with most Americans of the same “race”.

Unfortunately, the Census doesn’t distinguish between refugees/immigrants versus people born in the USA of the same race, such as white Russian immigrants versus white California immigrants.

Indeed. Simple narratives are rarely helpful.

Jonathan, you do realize people have lived out here for a very long time with lousy infrastructure? But now because people of color have been displaced to this part of the city it’s an issue? Or does this give you another reason to latch on to people of color for woke points?

Who is saying infrastructure in east Portland is only a problem now? It has long been officially recognized as a problem and significant resources have been allocated to address it. If there is a lack of visible progress, it is probably due more to the scale of the deficiency rather than the willful institutional ignorance you seem to suggest.

Many of the East Portland In Motion projects have been funded for years and not built. It was supposed to be a five year implementation plan for addressing the most critical active transportation issues in east Portland.It was passed by the city council in 2012. I give PBOT and their partners a solid B grade for funding these projects and a D grade for implementation.

East Portland will continue to need additional funding for active transportation projects to support the amount of additional housing being built in the area. Much of it in the form of low income housing.

Transportation infrastructure was sufficient in east Portland until they were annexed into the city and rezoned. The city created the transportation issues that are part of east Portland, but were slow to react when people were being killed. When will the Division Safety Project be completed? 2018?

Most of the low-hanging projects in EPIM such as sidewalk infill and pedestrian crossings were implemented in the first 3 years, thanks in large part to community pressure, postponing bond payments on the Sellwood Bridge, and then-Mayor Adams reading the riot act to PBOT staff. I’m still very pissed about the constant delays and lame excuses about 130s and 4M bikeways, the most important bike infrastructure in EP. Getting 136th and Powell Blvd funded took a lot of legislative effort, and now those projects are very much under way. Raising the roadbed of outer Foster to mitigate flooding was always a bit of a pipedream, as is the I-84 bike bridge at 132nd.

However, I agree with your grading. A great deal of the funding came in spite of PBOT push back. US Senator Jeff Merkley who was a state legislator for EP way back when, has been a huge help, as well as Jessica Vega Pedersen and Shamia Fagen (EP has 10 state legislators representing bits and pieces of it), Metro, ODOT (believe it or not), and most of the city transportation commissioners.

Apparently there’s now a community effort to start EPIM2.

Parkrose for example was annexed by Portland in 1980, so I think the city has had time to deal with the scale of the problem. They’ve just chosen not to.

Most of East Portland (including Parkrose), Cully, and Brentwood-Darlington were annexed between 1986 and 1991, with Gresham expanding in concert, but most of Pleasant Valley and areas near the airport were annexed in the 1960s and 70s, and parts of Lents way back in 1913. The City of Maywood Park was incorporated in the 1970s in a partially successful bid to try to block I-205. There are still some small pockets near the county line that still haven’t been formally annexed.

There was an effort in the early 80s to form a separate city, Columbia Ridge, but it was ultimately blocked in the courts. It would have been based on the giant “community groups” the county had in lieu of neighborhood associations: Wilkes, Parkrose, Centennial, Powellhurst-Gilbert, and Hazelwood. Wilkes and Centennial has since been divided between Portland and Gresham. Parkrose was divided into the present Parkrose, Parkrose Heights, Russell, and Argay. Hazelwood lost some territory to Montevilla and to the newish Mill Park neighborhood. Only giant Powellhurst-Gilbert is still largely intact (with over 31,000 residents, it’s easily the largest neighborhood in Portland by population).

Wasn’t the driver for annexation of mid-county neighborhoods provision of sewer and water services? Not to say transportation infrastructure wasn’t a problem in 1980, but that wasn’t necessarily the focus of community members then. And you didn’t have today’s increased population and traffic that in combination with no-longer-sufficient rural-scale infrastructure resulted in the increased exposure to dangerous traffic conditions that community members suffer today. And given how many in east Portland have reacted to projects on 102nd and 122nd and Glisan and Division and Stark, it’s not clear how many folks want the solutions to these problems that are popular around here and that PBOT pushes.

The City “promised” all kinds of things, but only the sewers did they put in writing, and they still haven’t quite completed that project 30 years later. EP was already hooked up to Portland water as well as its own – now the city owns the EP wells and uses them during droughts.

I have no doubt that East Portland, as a separate city, would have grown as much as it has, with many of the same issues and problems. But instead of paying taxes to pay for improvements downtown, East Portland residents would be paying taxes for improvements in East Portland, with its own local representation (and its own forms of corruption). According to the county auditor, EP pays far higher property taxes per unit of value than pretty much anywhere else in Portland, and gets back far less from the city (even the City admits that.)

And without EP tax revenue, there’s quite a lot downtown that would have never been funded, including the huge city police station.

Thank you for highlighting this research, Jonathan.

I found it interesting how much the interviewees who drive appreciate transit for the resiliency and redundancy it can provide in their lives (even as they begrudge its insecurity and relative unavailability). This transit-as-backup consideration led even interviewees who primarily drove to try to find housing on transit lines accessible to their jobs and find housing that was relatively close to destinations, such that most of their driving trips were still pretty short; all interviewees’ commute trips by car were less than 3 miles if they lived in East Portland and less than 5 miles if they lived in Albina. That is to say, having a car while poor wasn’t found to necessarily expand employment opportunities; if the safety net of the transit network isn’t underneath you, you lack the confidence you can still hold down that job if your personal vehicle fails (a real concern for those on a shoestring budget).

Some highlights from my read-through:

Portland was one of the first cities to implement a network based approach to public transit coverage. Credit to Jarret Walker at Human Transit. This allows for easy access to entire region with minimal transfers. This network based approach to freeway management should be applied for congestion management. This means closing some ramps and slowing traffic for less fender benders. Currently ODOT uses travel demand based models for predicting need for infrastructure, which always results in more auxiliary lanes. So that’s congestion in a nutshell. Review I-64 5 ramp closures in St. Louis. It works. It’s not racist, its geometry.

“Most studies on retail and grocery access focused on disadvantaged neighborhoods that were heavily populated by low-income and minority populations. But in Portland, living near a grocery store was not really a problem…food price mattered more for access. And most the stores with lower prices clustered along the I-205 corridor in East Portland. I found similar results, in that nearly all those with access to cars in Albina traveled to East Portland for groceries seeking out lower-cost food.”

I now live on the East Coast, but I do miss worker-owned WINCO Foods in East Portland. Well-stocked, no frills, huge bulk section, cheap fresh veggies, meat, cheese, and brand-name goods, even very good fresh bread, all much cheaper than Walmart or Fred Meyers, with long lines of low-income shoppers. However, I don’t miss locking my bike at their stores – stuff was stolen regularly.

Great article.

The comment about not liking to ride Trimet “mostly because of their encounters with homeless people and people with untreated mental illnesses which also spilled over into overt racist acts against them or their children”. This is a very real issue. My son spent all last year commuting to school at the Marshall campus on Trimet with his diverse group of friends. He spoke of incidents almost weekly of homeless and mentally unstable people harassing them on the Max with racial slurs and other taunts.

But in Portland the homeless are a protected class or “vulnerable citizens” as the city likes to call them. So you’re never really victimized by this marginalized segment of our population. We can’t expect these poor folks to accept any personal responsibility or be part of society even when we continually devote tax dollars to “connect them to services” and attempt to fix their plight.