This two-part article is by Aaron Brown, founder of No More Freeways PDX and former board president of Oregon Walks.

TriMet has appointed Doug Kelsey as their new General Manager. Neil McFarlane stepped down last month, after serving in the top role for the Portland region’s transit agency for nearly a decade. A few weeks ago, The Oregonian conducted an exit interview with McFarlane. His comments are instructive and they help illuminate the disconnect between our region’s bold aspirations for twenty-first century infrastructure and the governing agencies that appear too hamstrung by ineffective transparency and accountability measures to provide the services our region wants.

His comments about a certain freeway project caught my eye:

Q: Last year, you spoke in support of several highway expansion projects as part of a proposed TriMet ballot measure. Do you think those projects are a good idea in the absence of a transit project, or a political necessity to get the transit project through?

A: I talked about them as a basket, but I do think those are good projects. TriMet has always advanced sort of a multimodal agenda and recognized that we’re part of the solution, not the only solution.

Candidly, I sometimes still don’t get some of the objection to a project like Rose Quarter. [A $450 million proposal would add auxiliary lanes and shoulders to Interstate 5 through the Rose Quarter.] We’re essentially widening a pinch point to be reasonable in terms of the ons and offs, and movements from one freeway to another.

We expect that the top brass at TriMet at least possess passing familiarity with our coalition’s opposition to this mega-project. We’ve rehashed our talking points to anyone who will listen, and will likely do so for years to come until the region’s leaders come to their senses.

Instead, we’ll speak, you know, candidly, about the absurdity of TriMet’s willingness to be an accomplice to this boondoggle, and what it says about the agency’s current priorities and understanding of our region’s forthcoming mobility challenges.

Candidly, the reallocation of billions of taxpayer subsidies into transportation investments that serve our communities better than freeways is nothing short of imperative for the success of our region’s myriad public health, climate, housing, congestion relief and anti-poverty initiatives. Any transportation investment that doesn’t start with the explicit intention to chip away at automobile use as the primary method to access jobs, education, and shopping has significant consequences for a planet with literal melting ice caps, a region with worsening congestion, and a city ostensibly committed to equity. Perpetuating the continued necessity of automobile ownership is especially unhelpful to the growing number of people in our region who are unable to own or operate a car due to age, (dis)ability, citizenship, or cost. With our changing (and aging) demographics, the number of Oregonians in these categories will only increase (to say nothing about waning consumer preference or the rise of autonomous vehicles).

Why does this matter? Well, candidly, TriMet’s general “¯\_(ツ)_/¯” stance about ODOT’s continued push for this outdated infrastructure is all the more baffling because it’s TriMet’s employees, customers, and the agency itself who stand to benefit the most from any removal of this antiquated, vestigial subsidy.

Every dollar our region wrestles away from ODOT’s freeway expansion plans is a dollar we can spend on infrastructure that addresses these anti-poverty, climate and public health initiatives. Whether spent on mammoth undertakings like a downtown light rail tunnel or on humble, smaller investments like bus-priority intersections or curb cuts, this paradigm shift makes TriMet that much more alluring as an option for Oregonians’ daily errands. $450 million represents a cost of over 7 times Portland’s 2016 municipal gas tax, nearly twice the affordable housing bond, nearly 1,000,000 curb cuts and 100,000 pedestrian signals or approximately $430 for every Oregon family of four. TriMet expects to make $120 million off of farebox revenue in 2017; the funds for this freeway expansion could fund free passes for TriMet’s current riders for almost four years. An agency that championed its ridership and stated role as a literal and metaphorical regional connector should advocate for more thorough skepticism of ODOT’s needlessly counterproductive freeway expansion boondoggles that both explicitly and implicitly hinder TriMet’s capacity to serve their customers.

Advertisement

For one example, TriMet should be loudly championing not only the institution of congestion pricing on freeways, but specific language in policy dictating that revenue raised from pricing is redirected into funding complementary to C-TRAN and TriMet service. Forget the logistical, justice-based and environmental reasons for funneling this revenue into increased people-moving capacity; it’s in TriMet’s own interest to clamor for a bigger slice of the pie, as an agency supposedly aiming to deliver service to more of its constituents as a competitive, enjoyable, reliable transportation option.

And to preempt a familiar retort, the “colors of money” argument that implies TriMet’s hands are tied by fiscal stipulations on congestion pricing revenue is a bit disingenuous. As ATU’s [TriMet’s union] Andrew Riley pointed out last year, TriMet is remarkably capable at maneuvering fiscal limitations for the agency’s priorities in what Riley asserts is the “elaborate shell game” of their budget.

Nothing but a lack of political leadership is preventing TriMet as an agency from being a more outspoken civic leader for reform of institutions like the Oregon Highway Trust fund. These reforms would help unlock more money for buses for East Portland instead of freeway lanes for Clark County’s exurban sprawl.

Given this perspective, TriMet’s riders should wonder just whose interests are served by this expansion. The senior citizen in Gresham, the single parent in Aloha, the new family in Kenton, the wheelchair-using teenager in the Jade District, the PCC student cursing under her breath waiting for a connection to the Sylvania campus – they’re all already mobility-limited and cash-strapped, and it’s difficult to imagine a transportation project more irrelevant to their needs than a half-billion dollar freeway expansion that won’t make their commutes any faster, more reliable, or safer.

These are Oregonians who would benefit tremendously from TriMet flexing some muscle and more deliberately interrogating the agency’s historic alignment with the twentieth-century freeway builders over the twenty-first century affordable housing, climate, youth, senior citizens, YIMBY, disability, immigrant, biking, walking, traffic safety advocates working in concert for a bolder, greener, more prosperous vision for our transportation in communities.

(Graphic: PBOT Enhanced Transit Corridor plan)

Candidly, the fact that TriMet is supporting freeway expansion instead of aligning itself with its constituents offers a window into the political and governing calculus that might explain why the agency is witnessing flatlining ridership despite a burgeoning economy, worsening congestion, and a population eager to take more transit. That McFarlane characterizes support of freeway expansion as part of a regional “balanced solution” is like me stating my diet of hamburgers, ice cream and the occasional salad is a balanced diet. I shouldn’t get much credit just for kale if I’m serious about eating healthier, and Oregon’s governing agencies shouldn’t get credit for a package of investments that collectively fail to prepare us for demographic, climate, and economic upheavals coming our way. In this extended metaphor, I’m frustrated TriMet don’t see the moral, economic and governing imperative to speak up a little louder about the importance and wisdom of this region eating more greens.

What can be done about TriMet’s support of the budget? Stay tuned; part two of this series will look at the political and structural opportunities advocates see in the next few weeks, months, and years to encourage TriMet to better serve the Portland region. –> UPDATE: Here’s part two.

— Aaron Brown, @ambrown on Twitter

Never miss a story. Sign-up for the daily BP Headlines email.

BikePortland needs your support.

Thanks for reading.

BikePortland has served this community with independent community journalism since 2005. We rely on subscriptions from readers like you to survive. Your financial support is vital in keeping this valuable resource alive and well.

Please subscribe today to strengthen and expand our work.

Aaron, if you haven’t done so already, you need to go to a national transit convention. Many of the transit operators believe that AV will doom the present form of transit that involves just buses and trains, as opposed to the broader definition of transit which also includes bicycles, walking, cars, anything that moves people. You may not believe in it, BP readers might not believe in it either, but many of the transit operators do believe in it and are convincing elected officials of a future based upon AV, who are happy to be convinced because they are car drivers themselves and want that extra capacity that AV seems to promise for them. It may be a false promise based upon a lot of fallacies, but that hasn’t stopped people from believing even stranger things.

As long as he understands basic geometry and physics, we shouldn’t have an issue.

I don’t talk too much about AVs in this piece (or in the second half running tomorrow) but I absolutely agree that a lot of folks aren’t paying enough attention to it, and that the folks that *are* paying attention to AVs don’t properly understand the enormous potential they have to transform our communities (for better and for worse.) I think the most important thing to say about AVs is that this is less a question of technical design and more of a question of policy priorities and values: who will determine which streets they’re on, what speeds they travel, and what rights AVs have as they enter our cities? How do they interact with transit; are they supplementary, compliemntary, or oppositional? A world in which we use AVs to cover some of the last-mile problems particularly in outlying suburbs makes a lot of sense, especially if we double-down on transit investments. A world in which everyone uses AVs for every trip sounds like carmeggedon, and a world in which every street is clogged with driverless cars in a nightmare scenario.

Either way, the need for accountability, transparency, and engagement with community priorities is crucial with getting these decisions right.

Aaron, I agree with you about the carmaggedon analogy, but it also helps to understand that at its core, ODOT (and all the other DOTs) is about moving vehicles while Trimet (and all other transit agencies) is about moving people. ODOT has a focus on moving freight, on rail, by large semis, in smaller delivery trucks, in SUVs, and yes, even in single-occupancy-vehicles. They don’t particularly care about people, except upon how those people interact with freight and cause delays when they have crashes. I’m oversimplifying, of course.

TriMet is trying to find the most efficient, cheapest, safest way to move ALL people across the metro area. ALL PEOPLE. For the able-bodied, TriMet currently uses a system of buses, LRT, trolley, gondola, commuter rail, etc. For the disabled-bodied, they use a combination of their own lift vehicles, hired transport (including cabs), and shuttle buses (for example, Ride Connection.) The costs for moving able-bodied people is far lower than for disabled people, a small fraction per-rider in fact, hence the very real attraction of AV for TriMet. If they can move the disabled just as cheaply and safely as the able-bodied using the same technology, then on the long-term the transit system becomes far more efficient.

Let us assume that in 2300 AD all freeway traffic is AV. All freight will be moved by robot trucks or something similar, without people; all people will be moved by small 1, 2, 3, or 4-person AV pods. Given such a scenario, it is fair to say that both ODOT and TriMet (who uses Metro to do much of their long-term planning) has modeled the traffic of AV in the Portland region and have probably discovered where many of the future bottlenecks are likely to be. And where are the worst? Yep, you guessed it…

“Let us assume that in 2300 AD all … all people will be moved by small 1, 2, 3, or 4-person AV pods.”

To me, this doesn’t seem physically possible, certainly not 300 years from now when PDX will be much, much more crowded than today. Putting EVERYBODY in tiny-capacity vehicles will not work in terms of the needed material, energy or urban space. And what about that part of the population who won’t be able to afford it? Throw them to the lions?

This is a dangerous assumption, but it’s out there, and people are using it as an argument to abandon mass transit. They ask, why perpetuate a system that’ll be obsolete in even 20 years? They want cities to abandon rail lines, busways and transit-carrying bridges and tunnels to make space for more small, private vehicles. It’s selling the farm. In an era of rapid urban growth, we’ve got to invest more in mass transit, not less.

You may be totally right, or completely wrong about the world 20-30 years from now (forget 300). There’s no way to know at this point. Just as a reference point, it takes more energy per passenger to run TriMet vehicles than it would if everyone drove a small car. If AVs are small, light cars, and are electric rather than gasoline powered, from an energy standpoint, we’d be better off ditching transit. There are plenty of other standpoints, some of which would tell us to keep transit, but all are based on a range of assumptions about the future that are just guesses.

It makes no sense to abandon transit now, but I am less sure if we should be doubling down on projects like new Max lines. Transit-only lanes and congestion pricing seem like safe bets, and are easily reversible if they don’t perform or circumstances change.

David, i think we’re in agreement. The point i’m getting at is that TriMet and ODOT inherently have opposing goals, if TriMet is truly committed to provision of transit mobility and ODOT is unfortunately only worried about moving vehicles.

My point (and I hope I make it more clear in Part 2)

is that there’s no reason TriMet as an agency can’t demand more of the region, of ODOT, and of the state legislature. Their failure to do so is only hindering their efforts to be a meaningful provider of transit.

https://bikeportland.org/2018/03/22/guest-post-candidly-trimet-part-two-272088

>>> It may be a false promise based upon a lot of fallacies, but that hasn’t stopped people from believing even stranger things. <<<

It almost doesn't matter. AVs will be the biggest shift in transport since the advent of the car. It is impossible to predict what will happen. I happen to agree with the transit operators, because it's the most logical outcome, but the reality is that no one knows, or even can know. The only thing I feel confident about is that things will change.

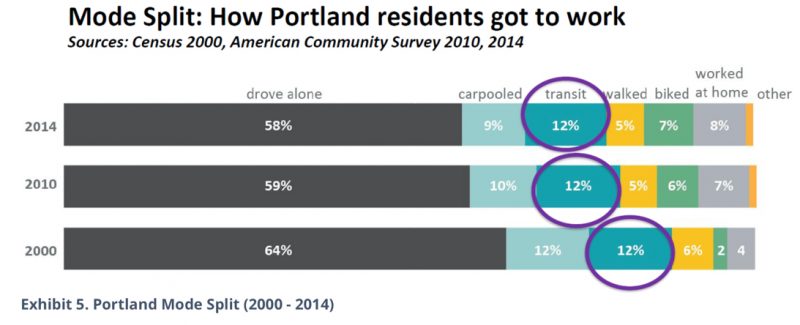

It’s good to see that the number of people who drive alone dropped also 🙂

The number probably rose, given the population rise, but the percentage did drop, even if ever-so-slightly.

The mode share split of commutes to work dropped. This is not the same thing as you write. I think the number of people who drive alone has never been higher than now in our city (though I don’t have the numbers to hand). I start to wonder if PBOT is deliberately obfuscating this point by using the measures that it does. Sorry to be a downer, but this is important. Yes, the mode share is an improvement and I am happy for that, but the reality of our transportation situation is horrific.

I know what I wrote and why. I was in no way suggesting that there are less cars on the road. One can also say that although the mode share of cycling has remained stagnant, there are more cyclists than ever…so no need to increase investment 😉

Actually, now that I reread what I wrote…I can say I worded it wrong. I meant to say that the percentage dropped. Mea Culpa.

I agree with you that the reduced percentage of car trips is a good thing.

Head of ODOT is appointed at the state level.

Head of TriMet is appointed at the state level.

Any doubt why they are on the same page?

A major part of the problem is that many transit agencies are led by an executive official who mostly pays no attention to and has deep misconceptions about planning/operations issues. Because of this, staff, uncertain what agency priorities are, simply work to preserve the status quo.

The candidly misguided approach to transit and transportation investment characterized TriMet’s top leadership has also reached down to the planning staff. Some planners at TriMet have the ¯\_(ツ)_/¯ attitude and don’t see what the big deal is. Some see the freeway as a necessary compromise to get transit funding, an inevitable political reality. But at the end of the day, running buses and trains is a mean and not an end. The ultimate goal of a transit agency ought to be providing equitable access and mobility to every person regardless of their age, income, and physical ability. Freeway expansion projects go directly against that goal.

Totally. Tomorrow’s piece will talk about that more in depth; stay tuned and thanks for reading!

Trimet purpose is to transport pedestrian and only pedestrian. Oregon needs to widen freeway in the PDX AREA for commercial transportation since it is funded by fuel tax dollars. So let’s be fair to everyone using Oregon freeways in the PDX area.

Why is ODOT always on the back burner when it comes to improvement and maintaining proper traffic flow on Oregon highways which has, been and currently paid for? Does somebody needs to get fired or what? What’s is the problem?????

I am trying to better understand your comment.

What is “proper traffic flow”? How many cars per minute? Or what speed? And what is it that makes this proper?

Also, people burning gasoline has a large effect on other people. So why should the tax on this be only used to ease the time of those people burning the gasoline, and not those who are living with the fallout?

Why does Oregon need to widen the freeways in the Portland Metro? If faster transport of commercial goods is the goal, then maybe we should discourage individuals from clogging up the freeways with their cars, both by implementing congestion pricing and by improving transit and other alternatives.

Follow the money and where decisions are made. A bunch of white dudes with white hair from the suburbs teaming up with ODOT/TriMet at JPACT.

Ed, i imagine you’ll like part 2, running tomorrow!

Probably much like many things in Portland. We scream equity but only when it benefits our white agenda. Not much has changed from the roots of Oregon’s past to now. I don’t see anyone voting for people of color as city commissioners/ mayor, you know, those folks who fight over fund distribution and have the power to change things.

Doug, of the five major candidates running for the open Saltzman seat, four are non-white dudes, including three women of color. I’d personally be shocked if at least one of them didn’t make the runoff. Andrea Valderrama and JoAnn Hardesty, in particular, have extensive history in grassroots organizing and advocacy for tenants and transportation justice.

This is the same agency that could have, for free built bicycle and people freeways along most of their lines for pennies. But they didn’t. It’s no surprise they bow down to the almighty car. Portland crush hour traffic is never going away as long as it’s free to drive during crush hour.

To be clear: there’s a lot of great planners and policymakers at TriMet. The agency has done a lot of great things over the years; as we’ll explore a bit more in the second half of the piece, this is more a question about the incentives that the political leadership feels to actually come through and deliver on infrastructure that best meets their needs.

Agreed! I am still amazed at the lack of vision displayed by not including a sidewalk on the streetcar viaduct from MLK to OMSI!

Streetcar is a City of Portland joint, not Trimet.

Absolutely spot-on; to extend your rationale, I think the reasons bike ridership has flatlined are similar to what you describe for transit but a bit more complicated by the fact that PBOT continues to tout and build projects that purport to support cyclists while spending taxpayer money to little effect because these projects are largely irrelevant and/or over-engineered, unsafe, or unpleasant for cyclists to use. It is completely unclear to me at this point what ‘new’ cyclist demographic PBOT is attempting to attract, or how they make their route and design decisions, because what they’ve come up with recently has all been pretty dismal, despite the PR from PBOT, the City and this web site.

The city of Portland is less than half of TriMet’s jurisdiction, and the people in Washington and Clackamas county pay the district taxes too, even though they almost all drive. You either have to tolerate a fairly moderate approach to cars from the transit governing body or do without the revenue from the suburban areas that don’t use transit as much. This is certainly not an easy trade off (especially since it means a large amount of money is spent of seldom used suburbanized routes like WES and far-flung MAX segments), but it is sort of the cost that’s paid to bring the ‘burbs into the fold.

lame

Counting work-from-home in the mode split for transportation doesn’t make sense. Transit share is actually 12.5,12.9,13% if you remove the work-from-home “commutes”. It needs to grow more, sure.

Bringing Tri-Met under the control of the locally-elected Metro Board is long overdue.

Politically, I’m not hopeful that the Metro Councilors will ever act on this –but the community could make it happen by initiative.

Who’s ready?