(Chart: BikePortland)

The unfortunately named new federal transportation bill, the FAST Act, is headed for a presidential signature after passing the House of Representatives Thursday.

While biking and transit advocates are sounding two cheers for the latest extension of the status quo (rather than the complete car-centrism favored by Koch-funded advocacy groups), it’s a good time to consider the ways transportation differs in cities across the country.

This year, the Portland metro area will spend about 30 times more tax dollars for TriMet operations alone than its cities have for biking improvements or programs.

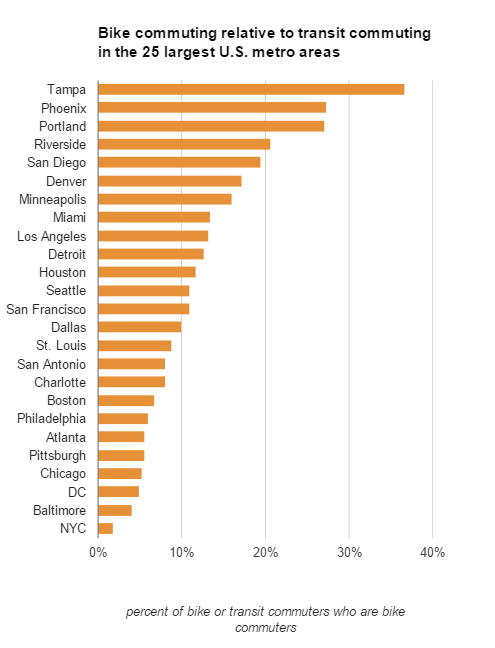

Here’s an interesting fact along those lines: though bike commuting is nearly insignificant compared to mass transit commuting in some metro areas, in other metro areas it’s basically a junior partner.

There’s no question, of course, whether biking or mass transit looms larger in American politics. Just look at the numbers: this year, the Portland metro area will spend about 30 times more tax dollars for TriMet operations alone than its cities have for biking improvements or programs.

At the federal level, $821 million was sent to bike-related projects last year. That’s 1.3 percent of the $65 billion that went to public transit grants.

I don’t mean to be arguing that bikes and transit are rivals, or that they aren’t complementary. The world’s best biking cities are all good transit cities. Anyway, far more tax money goes toward auto infrastructure than into either biking or transit.

But it is interesting to note that an attitude that makes sense in Washington D.C. or New York City — bikes are fine and dandy but mass transportation is the mode that deserves real money — doesn’t make sense at all in other cities like Tampa, Phoenix, Portland and San Diego.

When you start comparing transit and bike commuting directly to one another, the variation among major cities is huge.

Advertisement

What’s going on here?

For some of these cities, biking does well compared to transit mostly because transit is so unpopular. Tampa, Riverside and Detroit are the three largest metro areas in the United States with no light rail or metro system at all.

But why are they right next to decent transit cities like Portland, San Diego, Denver and Minneapolis?

Well, it’s hard to say. But here’s one possible factor:

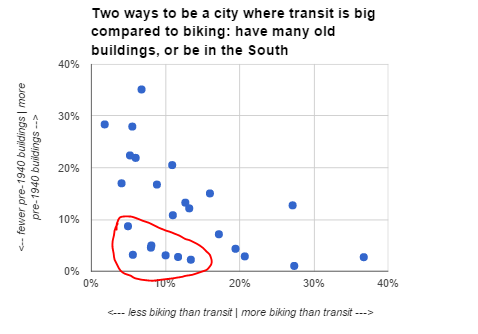

Do you see the trend?

Here’s a cheat sheet: the cities circled below are Miami, Atlanta, San Antonio, Houston, Dallas, Charlotte and Washington DC.

With the exception of most Southern cities (I’m not sure why) there’s a simple rule here: Unless you’re in the South, the more buildings you have that predate mass automobile ownership, the more transit-oriented your city tends to be. But if more of its buildings went up in the age of auto-oriented planning, your city is probably relatively more suitable for biking.

The Portland region’s transit system is pretty good, and that’s worth celebrating. But it’s not nearly as good as DC’s or Chicago’s — and unless we switch back to building 1920s style density someday, it probably never will be. Meanwhile, as TriMet prepares to use the renewed federal status quo to fund two big transit investments in Southwest and Southeast Portland, local officials ought to ask themselves: are we doing enough to make sure that bicycling isn’t an afterthought?

— Michael Andersen, (503) 333-7824 – michael@bikeportland.org

Thanks for reading.

BikePortland has served this community with independent community journalism since 2005. We rely on subscriptions from readers like you to survive. Your financial support is vital in keeping this valuable resource alive and well.

Please subscribe today to strengthen and expand our work.

There are too many variables here. My experience.

Phoenix, the last mile is more like 2 miles. So bike and bus are a natural selection.

Denver has pretty poor infrastructure for bicycles, but a great transit system. So hence more bike on bus to get around the bad spots.

Minneapolis is more weather related. Great bicycle infrastructure, ok transit and very cold or snowy days.

Yes, Weather likely plays a huge factor (both too hot (South, Phoenix) and too cold (Denver, midwest))

Dave, there are clear counterexamples to the weather theory of bike mode share. I bet it’s an influence, but I think that infrastructure, density, culture, and motoring costs all outweigh it heavily.

Denver monthly minimum (December) high temp – 29.9 F. Stockholm monthly minimum (January) high temp – 30.4F. Denver bike mode share – 2.9% (2012). Stockholm bike mode share – 6-7% (2014). Copenhagen is not THAT much warmer with a monthly minimum high temp of 36.5F and a 20+% bike mode share.

Atlanta monthly maximum (July) High temp – 89.1 F. Osaka, Japan monthly maximum (August) high temp – 92.1%. Both are humid. Atlanta bike mode share – 0.9%. Osaka bike mode share – 25%.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Denver

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stockholm

http://denverurbanism.com/2013/09/denvers-bicycle-commuter-mode-share-increases-20-in-2012.html

http://streets.mn/2014/07/11/stockholms-steep-climb-to-double-cycling-mode-share/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Atlanta

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Osaka

http://www.cityclock.org/urban-cycling-mode-share/#.VmH_EHarRD8

Too hot isn’t a big factor, it’s not like you going to slip and fall.

I am talking about physical barriers here.

we have a trimet payroll tax, maybe it is time for a bicycling payroll tax as well!

This is a really peculiar comparison. To be at the top of the list you can have really good bicycle use or really poor transit use.

It’s been years since I was in Tampa, but it didn’t strike me as either transit friendly or bike friendly. A little digging leads me to believe that Tampa is at the top of the list because transit is poorly used. Tampa residents take only 12.8 annual transit trips per year; Portland area residents take 58.4. Tampa ranks 124th in transit ridership per capita; Portland ranks 13th.

Check out transit rides per capita at:

http://fivethirtyeight.com/datalab/how-your-citys-public-transit-stacks-up/

Michael – good discussion. (As a planner and urbanist/ruralist, I have had the same thoughts [and frustrations] for a long time…especially during the funding calculations for crediting last mile trips during the CRC LRT Park & Ride planning.

Though to one of your minor points – even the 1920s urbanity might have been too late … since the development was resting on the prior infrastructure investments and the new investment trends toward the later part of the decade were auto oriented.

I think you’re on to the major explanation. Older cities built largely before the age of the automobile have central cores that were served well by mass transit, and so those investments were at least begun many years (decades) ago. More recent cities were/are designed more around individual transportation and so are spread out and corresponding mass transit system investments (think subway, for example) were relatively minor or nonexistent. Now that many cities are looking for alternatives to single occupancy vehicle madness, what’s cheaper, building a new or greatly expanding an existing mass transit system, or investing in bicycle infrastructure? (Meaning striping existing auto lanes in perhaps the majority of cases.)

Addressing a second issue raised in the article, mass transit systems are seen as more equitable across the range of ages and disabilities, etc., of the people that need to use them, so in many cases I imagine justifies the larger investments from a city-wide perspective (up to a point).

Focusing on the comparison of Chicago and Portland and their demographics–you can see that there’s a large discrepancy between population and density. Chicago has 2.8 million residents with a density of about 13 thousand per square mile. Portland has just under six hundred thousand with a population density of about five thousand per square mile.

I hypothesis that unless we reach substantial population figures similar to Chicago and D.C., we’ll continue to have just a “pretty good” transit system. Have you ever ridden the max out to the end of the lines–usually just a handful of people riding by then, pretty disappointing when you think about the resources needed to transport that few of numbers…

That’s true with any transportation system. Have you ever driven on an interstate highway through Wyoming or Montana?

or looked at the bike counts near the outer ends of the neighborhood greenways.

“That’s true with any transportation system. ”

I disagree, notwithstanding paikiala’s attempt at parity. But your statement draws attention to a larger question of the suitability of mass transit as a substitute for the car. In fact mass transit has never been and never will be a good substitute for the private car when it comes to point-to-point convenience. Therefore a century of hand wringing and appeals to fund/use mass transit has largely failed. But…. the bicycle IS a good substitute for most trips people actually take; it offers a mixture of point-to-point convenience that is often BETTER than the car, counterbalanced by some extra efforts associated (for some people) with biking.

Back to the question of investment dollars paying off and low utilization, mass transit is very expensive and suffers low utilization out at the (spatial and temporal) margins. Auto infrastructure is also very expensive and suffers less of the utilization drop off. Bike infrastructure (in the absence of cars) costs basically nothing and does not suffer from the utilization cliffs that mass transit does. Once the car menace enters the picture, defensive infrastructure comes into play but it has always been hard for me to count that against the bicycle.

This is useful, but I don’t think the population of the city is the main issue. Dallas, Phoenix and Houston have grown like gangbusters and are all approaching the population of the Chicago metro area. They’re all spending quite a lot of money to build transit systems … that haven’t yet resulted in a ton of ridership, because of the auto-oriented land use rules and practices.

Having a sweet transit system is a pretty good ingredient for improving one’s land use, but it’s not the whole recipe. For the most part those cities haven’t succeeded in actually changing their land use.

http://www.accessmagazine.org/articles/fall-2015/does-transit-oriented-development-need-the-transit/

(I have been reflecting that every time I hear it, “improving land use” is basically just a euphemism for “building less auto parking.”)

The argument was population density, not absolute population or population growth. Almost all of that growth in Houston, Dallas, Phoenix took the form of suburban sprawl, which is absolutely not transit-friendly nor bikable.

I always felt that transit and cycling were not allies. Sure, they have a mutual enemy in cars, but I believe they compete for the same hearts and minds of that unfortunately small percentage of the population that is willing to get from A to B without getting into a car.

It’s just an anecdote, and there were a lot of other things going on at the time (introduction of tuition, increase in intercity commuters, increased densification, increased segregation of cyclists from cars and, critically, loss of zero-tolerance traffic law enforcement), but when the bus service increased in Davis in the late ’80s there was a massive transition from bikes to buses. Too many other factors in play, but it was clear that the buses didn’t attract motorists out of their cars.

I ride a bike in Seattle instead of using the bus or train because from door to door the transit system is around double the time to bike, often more. Additionally the temperature stays within a tolerable range and it hasn’t been especially wet the past few winters (It’s sunny and in the mid 50’s today – I’m about to head out for a ride just because) so weather is rarely a factor. Traffic is just getting worse as more people move to the region so the bus is increasingly less of an option than it was to begin with, and the city is putting in bike lanes all over. I feel like there’s been an increase in folks riding bikes in the past year or so, and the people using autos seem to have – on average – been adjusting well.

The other important related item in Portland’s low cost bike growth – post the 1990s investment in bikeway crossings of the Willamette – has been the ‘undervalued’ legacy inner city urban commercial property along the old tram corridors…these commercial intersections spaced out at trolly car stop frequency become the rookeries of redevelopment once the coffee shop + bike shop + alt food / music venue [with housing on upper floor] opened.

It also helped that the early successful bike friendly trolley car arterials were not multilane arterials (or had been recently ‘improved’ / widened by ODOT – like MLK/ Union Ave).

I am still waiting for that PSU student research comparing / contrasting the success of the Interstate vs Mississippi corridors based on public fund ROI.

It seems like transit’s usefulness is mostly limited to commute trips. What about all of those short trips transportation agencies keep claiming to want to shift away from automobiles? Hauling a couple bags of groceries on the bus is challenging, and the bus only crosses your 3 mile radius in one straight line. You could bike to the grocery store before the bus arrives without breaking a sweat and more easily roll the load right in your door. And for maybe 10% of the cost of a transit system you could have dedicated safe bikeway for errands, school, and commute trips.

But cycling infrastructure doesn’t get 10% of the funds allotted to transit.

I’m very sceptical about this argument, in part because (as others have noted) it doesn’t account even for absolute percentages of bike and transit commuters, and in part because, generally[*], the same things make a city bike- and transit-friendly.

I’m only guessing without delving into the data (something that I don’t have time to do), but I suspect that the odd correlation you see has to do with cities in which both biking and transit are terrible options (as the comment above about Tampa suggests). To make this kind of comparison meaningful, you would need to include the actual percentage of users of each type.

[*] The one case I can think of would be a urban are that is relatively compact, making destinations relatively close, but with no concentrations of destinations, making it difficult to serve with transit, but also very bikeable. So far as I know there aren’t any urban areas like this, which would make it purely academic.

I have been thinking about my commute to work lately: NE Portland to Legacy Salmon Creek in Vancouver. It’s approx. 13 miles via car and about 15 miles via bicycle. The cost of driving is about the cost of one gallon of gas round trip (not including maintenance costs, ins., ect..), not too bad really. Then I’ve also toyed with taking transit. What I did was rode my bike to downtown Portland and hopped on a C-tran express bus that has one stop between destinations, drops me off two blocks from the hospital. This costs seven dollars round trip and takes about 98 minutes total round trip from point A –> B (including bike time). Thus, the car trip makes much more since. It’s about three dollars cheaper and 48 minutes faster. Biking takes 140 minutes round trip. You can see how transit and biking looses out in this particular scenario.

Now, what’ s interesting, I’ve recently been transferred to a new location: Rose Quarter. Which is just about one mile away from my house. This is so close, I’ll probably just run into work every morning. Bike commute when I don’t want to run. The catch is, CAR parking is FREE! However, it is much faster to ride in then drive because of all the traffic lights and parking–but still very temping on those really rainy days. Transit isn’t even an option. More expensive than driving, slower, and less convenient than even running. Transit looses again.

What if I had to PAY for parking at both work locations. I’d probably go with transit/bike to Vancouver and always run/bike to Rose Quarter (Portland).

I suppose you can say that transit can’t compete with cars when parking is free. And biking wins when it’s more convenient than transit/car commute.

My girlfriend lives about 3.5 miles one way to work. She drives. It’s free to park. The hospital that she works at does pay for Trimet, which is very nice but she often works swing and graveyard, which is inconvenient for transit commuting. Biking is an option, but the free car parking and convenience wins out. Her car gets around 40 miles/gallon. (I’m trying to push her to become a bike commuter, we’ll get there eventually!)

That first car trip might have been cheaper than bike plus bus, but you were injecting poison into the air and endangering human lives every single day you went to work. That makes no “sense” whatsoever, since you had an option not to do these things. It’s actually sense – less.

If I ride/bus combo everyday to work (22 days/month), I would spend 35 hours a month riding bike/bus. Too much time away from family and friends.